-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2016; 6(6): 209-214

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20160606.02

Emotional Variation in Professional Female Basketball Players during International Competitions

Renan Felipe Correia1, Clóvis Roberto Rossi Haddad1, Júlia Barreira Augusto1, Paula Teixeira Fernandes2

1Faculty of Physical Education Graduate Program – State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil

2Department of Sports Sciences - State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil

Correspondence to: Renan Felipe Correia, Faculty of Physical Education Graduate Program – State University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

There is vast interest by coaches on the correlates between athletic performance and athletes’ emotional answers and adaptations to training and competition stimuli. This study had the objective of assessing emotional variation in the athletes composing the Brazilian Adult Female National Basketball Team during different periods of training in a four-month span using the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes and the Profile of Mood States Questionnaire. Results showed that the athletes suffered no emotional variations during the different phases of physical training for the competitions in question. The possibility that these athletes engage in emotional coping mechanisms optimally during these training periods can explain these results. We believe that these results contribute to the investigations on efficient coaching practices for appraisal and management of athlete’s emotions and performance enhancement.

Keywords: Emotional Variation, Sports Psychology, Basketball, Sports Performance, Performance Enhancement

Cite this paper: Renan Felipe Correia, Clóvis Roberto Rossi Haddad, Júlia Barreira Augusto, Paula Teixeira Fernandes, Emotional Variation in Professional Female Basketball Players during International Competitions, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 6 No. 6, 2016, pp. 209-214. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20160606.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Coaches have broad interest in the effect of training and competition stimuli in athletes’ emotional responses during sports performance [1-4]. It is the role of Sport Psychology, an interdisciplinary area with common knowledge in fields such as psychology and physical education, among others, to study interrogations such as these [5].Lazarus [6] defines emotions as psychophysiological responses to relevant events or stimuli in certain environments. He proposes a theory, the “Cognitive Motivational Relation Theory of Emotion,” which states that emotions arise from the relationship that the individual has with its internal and external environments.Thatcher and Day [7] state that some of the inherent characteristic of sporting environments vary according to the demands placed on its individuals, containing elements relating to the duration of the event, its (un)predictability, novelty of stimuli, ambiguities, and inter - and intra – comparisons to fellow competitors. Daniels et al [8] states that in sports the achievement of goals leads to positive emotions and the failure to do so leads to negative emotions. According to Weinberg and Gould [5] and Barreto [9], the efficiency of elite athletes relates to their cognitive and psychological variables, which means the combination of biomechanical, physiological and mainly psychological factors for success. Thus, the deficiency / absence of some of these factors may limit optimum sports performance.Among the various major sports practiced throughout the world, basketball arouses scientific interest because of its dynamic gameplay [10]. It features a dynamic and unpredictable environment that enables unlimited options of physical and perceptual actions. The game requires from the elite player a high level of concentration, attention, speed in decision-making, and the use of multiple intelligences [11]. Thus, it is noted that competitive basketball is a sport with great potential as a stress generator due to its many environmental stimuli: the continuous need to display optimal performance under adverse circumstances, playing time, physical form, the presence of opponents, the need to win, and the need to build social status through the athlete's image [12-14].

1.1. On Training, Sporting Form and Emotional Variations

- Bompa [15] and Platonov [16] state that physical training is the most important element for the achievement of maximum sport performance. Matveev [17] defines this state as "sporting form," a multifaceted phenomenon, consisting of the physical, psychological, technical and tactical aspects of training.Some authors suggest the systematization of models for organized training processes that seek the achievement of sporting form. The efficacy of these processes hold solid support in the scientific literature. Among the most widely accepted are Matveev's Periodization Model [17], Verkhosansky's Block Training Model [18], and the model proposed by Bompa [15], which is an adaptation of Matveev's [17] model for American sport systems. With these models, the authors observed that an athlete's performance depends on their physical and psychological adjustment to their environment, and achievement of optimum performance results from the interrelation of these adaptations and the ability of the athlete to cope with stress.Recent research shows that psychological variables (concentration, motivation, anxiety, group cohesion, and stress) can interfere directly in the training of elite athletes [19]. Bompa [15], examining different periodization models and training methodologies, emphasizes how much psychological training is important and necessary to ensure high physical performance, which in turn, will bring improvements in discipline, confidence, willpower, perseverance, and courage for the athlete. A study by Nunes et al [20] examined the effects of a training program in internal training load, stress recovery state, immune-endocrine responses, and physical performance in 19 adult female basketball players from Brazilian National Team during a preparatory period (12 weeks). The athletes responded to the RESTQ-76 (Questionnaire Stress and Recovery for Athletes) [21] and underwent salivary IgA, testosterone and cortisol concentration, and physical tests. The research concluded that the proposed training brought about changes in the internal training load, which positively influenced the stress recovery states of the athletes.Arruda et al [22] complemented the study described above, but with 12 players in a two-week period. The objectives were to analyze the influence of periodization of strength training on mood states profile, verifying the occurrence of the "iceberg" profile in the POMS (Profile of Mood States Questionnaire) [23] and the response of salivary cortisol. The study concluded that different strength training contents did not affect the parameters investigated, indicating stability in the level of stress, and that the "iceberg profile" prevailed in all evaluated moments.Fronso [24] proposed an interesting analysis about the differences in stress level and recovery between genders and training phase in basketball athletes of both sexes. The athletes (16 men and 12 women) answered the RESTQ-76 during two training mesocycles and the results showed differences between the parameters investigated. Men performed better on the physical, sleep quality and self-efficacy scales. Another study [25] analyzed responses of total testosterone, cortisol and testosterone-cortisol ratio in relation to mood in professional basketball players. The study lasted one season and found no relationship between hormonal variables and scales of mood states during this time.Lukins [26] examined relationships between performance and psychological profiles in 19 female basketball athletes. The results showed that the players with the lowest scores on scales of fatigue and anger had the best performance on free throws during a championship. Hoffman et al [27] evaluated changes in mood states (POMS) and performance in professional basketball players. In his study, the vigor scale in the POMS correlated positively with the performance of the team.The different results showed above reinforces Samulski’s [19] statement that studies published on the role of emotions in sport are not yet conclusive. Thus, this research aimed to investigate the relationship between emotional variations in elite adult athletes in the Brazilian Female Basketball Team during different periods of training for international competitions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

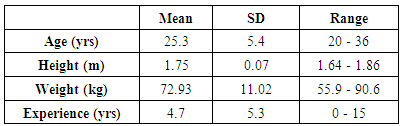

- We evaluated nineteen athletes named to the national team who participated in the South American Championships and International Basketball Federation (FIBA) World Cup. Of those, eight athletes (Table 1) were present in all stages of training camp and were included in this study. Although this may seem like a small sample size, we raise attention instead to its quality, due to the fact that elite athletes of international level make up a very small percentage of the population, and that at any given time, eight athletes in a national team might make up for more than half of its total participants.

|

2.2. Ethical Procedures

- The work meets all latest ethical publications standards and guidelines of the APA. The study was approved by University of Campinas’s Ethics Committee (30955514.6.0000.5404) Athletes were briefed in all research procedures and signed consent forms.

2.3. Instruments

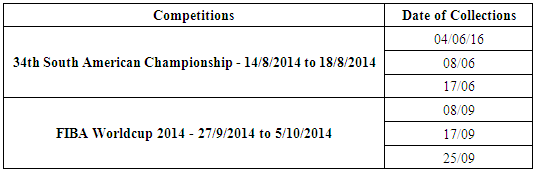

- The instruments used in this research for data collection were the RESTQ-76 (Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes) [21] and the POMS (Profile of Mood States Questionnaire) [23]. The RESTQ-76 is used to measure the current state of stressful events in athletes in conjunction with recovery activities. With 77 items divided into 19 subscales, following a standard Likert scale, it evaluates potentially stressful events, stages of recovery and their subjective consequences of the last three days / nights. The German and American Olympic Committees use the RESTQ-76 as their official training monitoring and evaluation instrument of [28].The POMS is an instrument containing 65 items that measures mood states across seven domains. Morgan [29] characterizes successful elite athletes in many sports as having the "iceberg profile" in the POMS, which reflects positive mental health, and is defined by low scores on the depression, fatigue, mental confusion and anger domains and high scores in the vigor domain. The "iceberg profile" is one of the best sources of athletic success forecast models and reflects a necessary mental structure model for optimal performance. We collected data in six different moments (Table 2). Procedures were done collectively, always under the same conditions, and lasted about 30 minutes.

|

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- All data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics were used to analyze the data, using GraphPad Prism version 6.07 for Windows [30-31]. To attest data normality, D'Agostino-Pearson Test was used. Parametric one-tailed analysis of variance (ANOVA) attested whether there were significant differences between the averages of the six collections. A post-hoc analysis test (Tukey Test) was used to determine where the difference resided. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

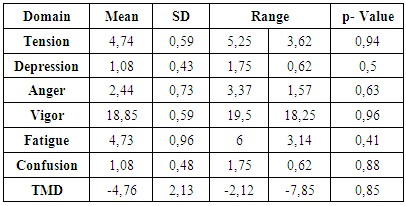

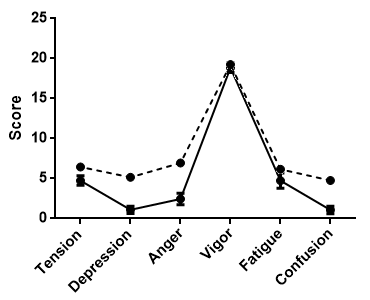

3. Results

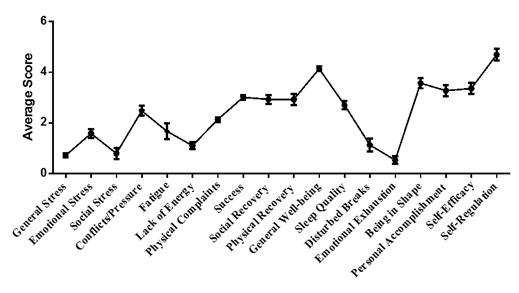

- As seen in figure 1, the players showed no significant emotional variations over the period investigated in all RESTQ-76 subscales:

| Figure 1. Average scores for each RESTQ-76 subscale during the six different periods of analysis |

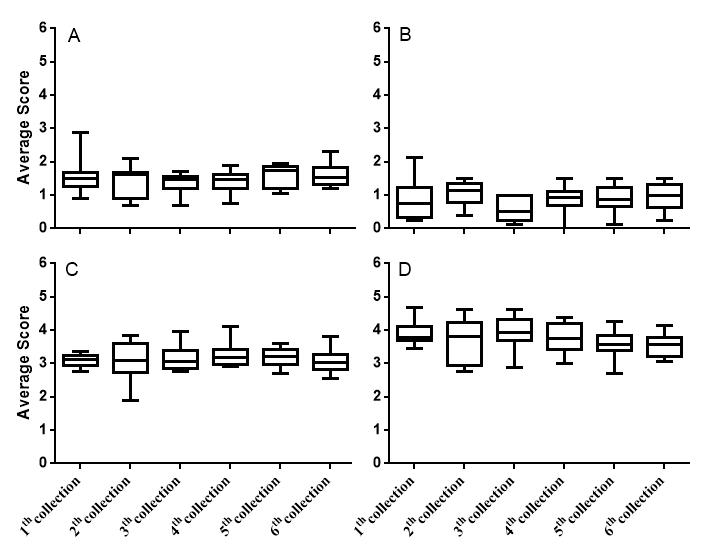

| Figure 2. A) General Stress Domain, B) Specific Stress Domain, C) General Recovery Domain, D) Specific Recovery Domain Scores of the RESTQ-76 |

|

4. Discussion and Final Considerations

- This study shows that the athletes of the adult female Brazilian National Basketball team showed no emotional variations during different training periods for two important international competitions. They also presented the "iceberg profile" in all periods investigated.According to the RESTQ-76, athletes seemed to cope better with sport-specific stress than general stress, such as being away from home and family and other personal matters. It could be possible that this scenario is a result of the interdisciplinary support given to athletes during all phases of competition, making them more psychologically prepared for sport specific stress than for general life stress. In addition, we question ourselves if all scores could be improved with psychological-specific training. Specifically to the POMS, recognizing the need for emotional arousal for optimum sport performance [32], we question ourselves to what extent the much lower scores in the anger, depression, and confusion domains, when compared to reference values, are a positive and beneficial trends for the athletes’ performance.The results presented here corroborate with the study by Arruda et al [22] for a similar population, which concluded that emotional parameters did not change during different training periods, indicating level of stress stability and that the "iceberg profile" prevailed in all moments. In turn, it disagrees with Nunes et al [20], which found positive emotional variations across training periods.The results of this study, in which elite athletes demonstrated emotional stability, even upon exposure to intense training processes and very important competitions on the international sports scene, raises new questions, inferences and hypotheses about the relationship of emotional variations and sport performance. This is strengthened when confronted by the fact that the scientific literature that questions this relationship has recently showed quite controversial results [20, 24, 33]. Mainly, we question if the emotional stability of the athletes are an outcome of intense psychological training and coping mechanisms or an outcome of insufficient training stimuli.Of these, we would like to briefly comment on the coping hypothesis for future research. Lazarus and Folkman34 defined coping as the ability to manage internal or external psychophysical-specific demands that exceed the individual’s resources. Previous research has pointed to the importance of coping in sports performance to help athletes regulate possible negative stimuli from sport environments [35-42], which could help explain the results presented in this study. A fact that strengthens this hypothesis is that all our subjects already operate in elite high-performance adult teams and are accustomed to high-level national and international competition. Given this context, we highlight the importance of the sport psychologist in the multidisciplinary teams that make up technical committees of high performance sports teams. We believe that these results contribute to the investigations on efficient coaching practices for appraisal and management of athlete’s emotions and performance enhancement. We hope that this research fuels further investigation relating scientific and practical evidence of the relationship between emotional responses and sports performance in elite sports.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The CNPQ (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development) provided funding source this research through its institutional program. The funding source had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor in the writing and decision to submit the finished article. The authors would like to thank Dr. Mariangela Salve for her suggestions on the final draft of this research paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML