-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2016; 6(6): 203-208

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20160606.01

A Qualitative Examination of the Sport Music Preferences of NCAA Division I Athletes

Zachary Ryan1, Daniel R. Czech1, Brandonn S. Harris1, Samuel Todd1, David D. Biber2

1School of Health and Kinesiology, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, U.S.A.

2Department of Kinesiology and Health, Georgia State University, Atlanta, U.S.A.

Correspondence to: David D. Biber, Department of Kinesiology and Health, Georgia State University, Atlanta, U.S.A..

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of the current study was to examine the sport music preferences (SMP) of NCAA Division I athletes. A secondary purpose was to examine SMP from a gender and contact sport type (collision, contact, limited-contact) perspective. Participants (n = 21) were male and female NCAA Division I athletes from a southeastern university. The consensual qualitative research (CQR) protocol was used to analyze the data pertaining to the music athletes prefer to listen to prior to participating in their sport. The results suggest that, overall; athletes prefer music that is fast and upbeat, pay more attention to the beat than the lyrics, and like rap and/or hip-hop music. Female and limited-contact sport athletes also reported listening to multiple genres of music, while male and collision sport athletes pay attention to the lyrics in select songs. Outcomes of the research and future research suggestions is discussed.

Keywords: Sport Psychology, Sport Music Preferences, NCAA Division I Athletes

Cite this paper: Zachary Ryan, Daniel R. Czech, Brandonn S. Harris, Samuel Todd, David D. Biber, A Qualitative Examination of the Sport Music Preferences of NCAA Division I Athletes, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 6 No. 6, 2016, pp. 203-208. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20160606.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Music has become an ever-present feature in the lives of individuals and is rated as one of the most important lifestyle activities [1]. 66% of athletes reported listening to music “several times per day,” and rated it as an important part of their daily lives [2]. Furthermore, the use of music to help with sport performance has become a growing area of research. In addition, fast music stimulates the body and music use during athletic and exercise participation can increase performance [3]. For example, rowers doing a 500-meter sprint had a shorter time to completion and more strokes per minute in a fast music condition compared to a slow music condition [4]. Similarly, perceived effort, positive engagement, and revitalization were all lowest during a training session with slow music when compared to fast music and no music conditions [5]. Furthermore, many athletes report listening to fast-tempo music when incorporating it as a mood-regulation strategy [6].The use of music during training sessions has potential to improve performance in competition by enhancing the quality and quantity of work done during training [3, 5]. While this information can be helpful to understanding the potential benefits of music use around sport participation, further research is required to understand why athletes use music and what music they listen to. In a study to understand why athletes listen to music during sport, the most common themes to be arousal regulation, enhanced focus, mood regulation, and to build team camaraderie [7]. Research indicates athletes most often use music for arousal and mood regulation, usually as pre-event preparation, which is consistent with previous research [2, 6, 8]. Following a music intervention, runners reported an increase in pleasant emotions and decrease in unpleasant emotions, which helped facilitate performance, from pre- to post-intervention [9]. Although music is often used during athletic training, differences in athletes’ sport music preference (SMP) needs to be studied further to understand the impact various types of music has on psychological and physical performance. While research indicates a difference in music preferences across genders, differences have not been examined specifically in a sport context [10]. Gender differences in SMP across sport types also needs to be investigated to understand how music impacts sport performance in practice and performance across a variety of sports. The previously mentioned research examined the impact of music across a wide variety of sport types [2-5]. The different types of contact sports area s follows: collision, contact, and limited-contact [11]. Collision sports, such as football and rugby, are those in which athletes will intentionally hit one another, inanimate objects, or the ground with great force. Contact sports, such as basketball and soccer, are sports in which athletes regularly make contact with one another or inanimate object but with less force than collision sports. Lastly, limited-contact sports are those in which contact with athletes or inanimate objects is not regular or is unintentional, like baseball and softball. It has been shown that athletes of different contact sport types have different levels of aggressive tendencies [12, 13]. That said, certain music preferences are related to higher levels of aggressive tendencies [14]. Consequently, past studies have suggested that aggression, or views about aggressive behaviors, can differ based on an athlete’s contact sport type [12, 13]. The current study utilizes the framework that contact sport type and gender may impact athletes’ SMP due to the different relationships between these two variables and aggression. Athletes of different genders and sport types may prefer to listen to different types of music prior to their sport depending on the levels of aggression they seek to reach before participation. The purpose of this study was three-fold. The first purpose was to qualitatively examine the overall sport music preferences (SMP) of NCAA Division I athletes. More specifically, the second purpose was to examine gender differences in SMP. The third purpose was to examine differences in SMP between contact sport type (collision, contact, limited-contact). The humanistic approach will be implemented through in-depth interviews and thematic analysis to fully understand SMP of each individual [15].

2. Main Body

2.1. Humanistic Approach

- The present study was grounded in the humanistic approach to fully understand how each individual experiences SMP in an individual context [15]. When utilizing this approach, the primary researcher must understand that each individual is different so that their answers can be viewed in the proper context. This is achieved by requiring the individual to relive their experience and look at it retrospectively [15]. In-depth interviews and thorough interpretation of the data permitted the primary researcher to learn about each individual’s experience and the significance of that experience.

2.2. Bias Exploration and Bracketing Interview

- As is the nature of qualitative research, the primary researcher is often a part of the instrumentation, and it is important to understand how their life experiences are tied to the topic of study [16]. The use of bracketing interviews can help to control for researcher biases in qualitative research [16]. The ability to “bracket out” beliefs and experiences aids in collecting data that is both valid and unbiased, in addition to preventing the researcher from using their biased judgment when interpreting the interview later. In this study, bracketing was completed for the purposes stated above, through a bracketing interview led by an experienced qualitative researcher. This interview gave information regarding the researcher’s own experiences and knowledge regarding the music preferences and the use of music around sport participation. Due to personal experience with music and sport and knowledge and general interest in what kind of music people listen to, it was necessary for the primary researcher to bracket out biases towards athletes’ sport music preferences.

2.3. Participants

- NCAA Division I athletes from a southeastern university that reported listening to music prior to most, if not all, competitions and/or practices for at least three years were included in the present study (n = 21). Sampling continued until saturation was achieved, meaning there was sufficient data collected to account for all aspects of the phenomenon studied [17]. Males (n = 13) and females (n = 8) from the three different contact sport types (collision, contact, limited-contact) were included in the study. The mean age of the participants was 20 years (SD = 1.55). The participants were White (n = 12), Black (n = 7), or Biracial (n = 2) from the following sports: football, baseball, softball, men’s and women’s soccer, and men’s and women’s basketball.

2.4. Instrumentation

- 1. ResearcherThis study utilized a semi-structured qualitative design to collect data, making the primary researcher the main instrument. The researcher was responsible for conducting, recording, and transcribing the interviews for all 21 participants.2. iPad MiniAn iPad Mini with the app “Recorder Plus” was utilized to record the participants’ responses to the interview questions.

2.5. Procedures

- After attaining IRB approval, participants were recruited from undergraduate kinesiology classes, contacted through email or in person, and asked to participate in the study. Each participant was given an informed consent and further educated about the nature of the study. The participants were interviewed separately and in person in a closed office. Participants were informed prior to participation that the interview would be recorded and transcribed for accuracy. Participants were told they could stop at any moment for any reason without any repercussion.

2.6. Interview Protocol

- This study utilized semi-structured interviews to understand the individual experiences of each participant. This type of interview protocol also allowed the researcher to ask probing questions to obtain deeper meaning. The questions developed for the interviews were open-ended so that athletes could answer by speaking through their own experiences. The interview consisted of six open-ended questions, such as the following: “What characteristics do you look for in the music you choose to listen to prior to participating in your sport”? Probing questions were asked using the verbiage of the participant to gain deeper understanding of the experience of each participant.

2.7. Data Analysis

- The consensual qualitative research (CQR) protocol was utilized [18]. CQR is viewed as an effective methodology for analysis because it requires multiple researchers to examine the data and reach a consensus about its meaning [19]. The first step of CQR is to create a research team with expertise in qualitative research analysis. An external auditor, an expert in CQR and a sport psychologist, served as a “check” on the analysis. The members of the research team were trained in CQR [18, 19]. Following data collection, the interviews were transcribed by the primary researcher. Each research team member reviewed a set of the transcripts for accuracy to prevent fatigue and reduce the repetition involved in analysis, and the primary researcher reviewed all transcripts [18, 19]. The research team was given broad topics to utilize when generating themes within the transcripts in order to focus the data analysis on answering the primary research questions. The individual research team members reviewed each line of the transcripts in order to create themes that thoroughly depicted how the participants described their experience [19]. The research team then discussed the themes they derived independently to reach consensus on and cross-analyze a set of domains. Domains are topic areas used to help group data pertaining to similar topics and allow the segmentation of the interview data. The research team worked together to create categories that described the common themes found within each domain across all of the cases [18, 19]. Cross-analysis also entails determining the prevalence of each category within the data and creating categories that describe the common themes across most of the cases [18, 19]. Categories were created if data pertaining to that specific category were prevalent in five of the seven transcripts. Categories were then summarized with core ideas, which provide a clearer picture of what was said in a more concise manner that is comparable across cases, while staying as close to the interviewer’s exact words as possible [19]. The domains, categories, and core ideas extracted, along with all of the transcripts, were then sent to the external auditor for their feedback and to gain an additional perspective. The final step of CQR was member checking. The coding scheme, including the domains, core ideas, and categories were sent to the participants via email, with the option of receiving their transcript, in person, if desired. Participants were asked to give their feedback on the coding scheme and how accurately it reflected their experience and responses to the interview questions.

2.8. Results

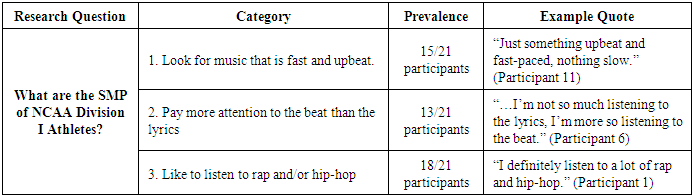

- Data analysis revealed the following thematic categories related to athletes’ SMP. These categories of SMP were grouped first by the research question they sought to answer, and then further by the specific interview questions that had been asked to help answer the research question. In addition, quotes from the participants are included to better illustrate each thematic category. The following tables highlight thematic responses to research question 1 (see table 1), research question 2 (see table 2) and research question 3 (see table 3).Research Question 1: What are the SMP of NCAA Division I Athletes?

|

|

|

2.9. Discussion

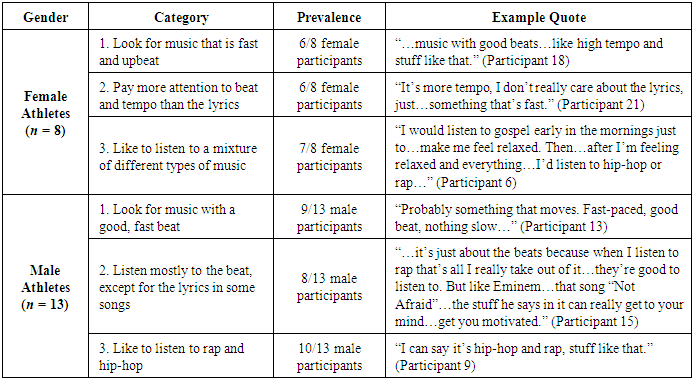

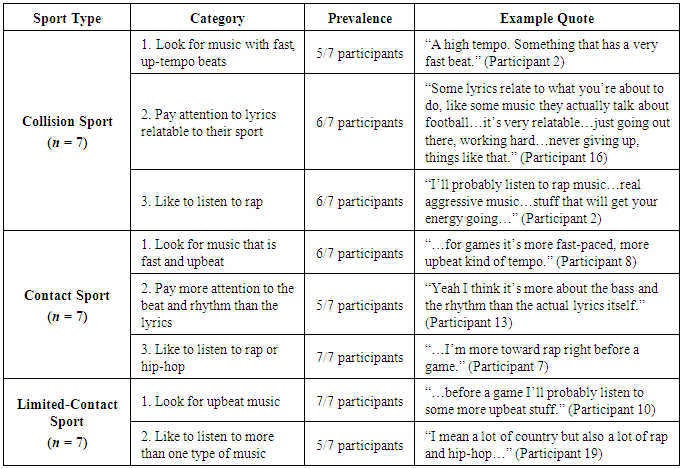

- The purposes of this study were to qualitatively examine the sport music preferences (SMP) of NCAA Division I athletes overall, by gender, and by contact sport type (collision, contact, limited-contact). Specifically, the study aimed to understand the musical genres and characteristics athletes preferred to listen to prior to participating in their sport. The data revealed three major categories related to athletes’ SMP: 1) look for music that is fast and upbeat, 2) pay more attention to the beat than the lyrics, and 3) like rap and/or hip-hop music.Look for Music that is Fast and UpbeatEach of the athlete groupings preferred music that was fast and/or upbeat. Fast music stimulates the body and that music use during exercise or athletic participation can increase performance [3]. While the present study focused on athletes’ preferred music prior to participation, many athletes believed their performance would be negatively impacted without their music. The preference for fast and upbeat music prior to sport is consistent with previous research [6]. Upbeat music was also mentioned as a means of increasing energy levels prior to sport, which is supported by research of athletes using upbeat music to help increase arousal [7]. Multiple athletes in the current study mentioned that the music they chose helped to increase their energy levels in a similar fashion to increasing arousal. Paying More Attention to the Beat than the LyricsA majority of the athletes interviewed said they were more attentive to the musical characteristics, specifically beat or rhythm, rather than the lyrical content. The importance of musical characteristics as a preference in song selection and how it impacts sport performance is a growing area of research. Researchers investigated tennis players’ use of music to manipulate their emotional states and found that the musical properties of songs largely influenced the music they selected before matches [20]. Furthermore, 61% of athletes surveyed felt the effects on their performance from music came from “aspects of the music” such as, “the beat of the music” [2]. While greater emphasis seems to be placed on musical characteristics than lyrical content, the male and collision sport athletes varied slightly from the rest of the athlete groups in the study. Both male and collision sport athletes noted that they attend to the lyrics of select songs that they listen to before their sport participation. Specifically, these athletes paid attention to lyrics they felt related to them personally, to their sport, or their team. While lyrical content is part of the decision-making process in music selection and can impact sport and exercise motivation and enjoyment, it is not the most important selection criteria prior to performance [20, 21]. Like to Listen to Rap and/or Hip-Hop All but three of the 21 athletes interviewed mentioned rap and/or hip-hop as genres of music they liked to listen to prior to participating in their sport. In relation to music preferences, this could be identified as a preference for energetic and rhythmic music [1]. As previously mentioned, this category of music preferences is characterized by rap/hip-hop, soul/funk, and electronica/dance music. This differs slightly from what was found by by previous research, where 32% of the athletes surveyed reported a preference for intense and rebellious music prior to sport [2]. This type of music is characterized by heavy-metal, rock, and alternative music. In that same study 28% of the athletes preferred energetic and rhythmic music. Only three athletes interviewed in the present study made any mention of listening to music that would be considered intense and rebellious, and all listened to those genres in conjunction with rap or hip-hop. Listening to rap and/or hip-hop was common across all contact sport types. As stated previously, past research has found a positive relationship between aggression and both a preference for rap music, as well as playing a collision sport [12-14]. The results of this study do not support this notion entirely, as aggression was not measured and a preference for rap music was found across all of the contact sport types. Future research would need to focus on collision sport athletes only in an effort to support the relationship between all three variables.Both males and females expressed interest in rap and/or hip-hop music, but females and specifically limited-contact athletes, also expressed interest in other genres of music during sport performance. While research indicates males often prefer rock and heavy metal and females pop music [10], athletes’ music preferences have been found to differ for their everyday music listening and music listening prior to their sport [2]. While the present findings indicate rap and/or hip-hop to be the most commonly preferred genre of music, such preferences require further investigation to understand how sport type or personality may impact preference.

3. Conclusions

- The present study examined the music NCAA Division I athletes preferred to listen to prior to participating in their respective sport. The data was examined for athletes overall, by gender, and by contact sport type (collision, contact, limited-contact). The results pointed to athletes looking for music that was fast and upbeat, paying more attention to the beat than the lyrics, and liking rap and/or hip-hop music. Male and collision sport athletes were found to pay attention to the lyrics of select songs they found relatable to themselves or their sport/team. Female and limited-contact sport athletes reported commonly listening to other genres of music in addition to rap and/or hip-hop. Future research should examine cultural and competition level differences in SMP. Understanding differences in SMP during practice and competition could help further understanding of how music may impact arousal regulation and relaxation.Due to the sample for this study being small and purposeful, the results cannot necessarily be generalizable to the entire population. The study also only focused on athletes at the NCAA Division I level, and it is possible different SMP could be found from athletes at different levels of competition. The sample of this study was also comprised of majority males, which could give an uneven picture of SMP for NCAA Division I athletes overall. Furthermore, the collision sport group was comprised of only males, due to the lack of NCAA Division I female sports considered to be collision. This could create an unbalanced look at SMP for this contact sport type. It could be appropriate to create a more balanced gender sample in future studies. The final limitation for consideration is the fact that only one interview took place between the primary researcher and athletes. Additional interviews might have given the researcher more in depth data to analyze, as well as a chance for the researcher toFuture researchers should include measures of aggression to understand the relationship between contact sport type and music preferences. Overall, the present study provides a deeper understanding of SMP in the context of sport type and gender that can help athletes, coaches, and sport psychology consultants prepare athletes for practice and competition.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML