-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2016; 6(3): 100-105

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20160603.06

Utilizing a Short-term Fitness Program to Address Time Constraints among Fitness Participants

Pamela Wicker1, Dennis Coates2, 3, Christoph Breuer1

1Department of Sport Economics and Sport Management, German Sport University Cologne, Cologne, Germany

2Department of Economics, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Baltimore, USA

3Higher School of Economics, National Research University, Perm, Russia

Correspondence to: Pamela Wicker, Department of Sport Economics and Sport Management, German Sport University Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Time constraints are a major barrier to participation in physical activity. The purpose of this study is to examine (1) how participants in a short fitness program (two 30-minute sessions per week over a four-week period) change the time allocated to other weekly activities and (2) what factors explain the differences in time allocation. A quasi-experimental design was chosen including a physical entry test and a pre survey, a four-week training intervention, and a physical exit test with a post survey. The program was provided by over 300 German fitness clubs. The voluntary and free of charge program was completed by 10,095 test persons. The results of the t-tests show that participants allocated significantly less time on work, homework, caring, education and learning, repairs, social contacts, and other hobbies to find time to go to the gym. Regression analyses indicate what factors explain differences in time allocation between the post and pre survey. A controversial finding was observed for body-mass-index which was significantly and positively associated with time spent on three activities: The higher the body-mass-index, the more time participants allocated to caring, education and learning, and repairs during the training period. To conclude, participants found time to go to the gym by reducing the time allocated to several weekly activities rather than substantially reducing one activity. For people with higher body-mass-index participation in the fitness program may have been a start to a more active life in general.

Keywords: Body-mass-index, Fitness, Health promotion, Physical activity, Public health

Cite this paper: Pamela Wicker, Dennis Coates, Christoph Breuer, Utilizing a Short-term Fitness Program to Address Time Constraints among Fitness Participants, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 100-105. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20160603.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- One of the most frequently stated reasons for not participating in physical activity is no time [1, 2]. Accordingly, previous research has examined the time constraints of physical activity in more detail [3, 4]. While working time was found to be not significantly related with the likelihood of participation in physical activity [5, 6], the time spent on looking after children and caring for family members had a significant negative effect on the likelihood of participating in physical activity [6, 7]. Given the health benefits of participation in physical activity documented in previous research [8-10], there is surprisingly little research on the role of time in explaining health-producing behavior. Mullahy and Robert [11] found that more-educated individuals tend to allocate more leisure time to physical activity while sleeping less and working more than less-educated individuals. Time constraints have been integrated into the business model of commercial sport providers (e.g., gyms); their long opening hours allow more flexible training sessions. Yet, there is evidence that the prices are set in the awareness that many customers will not exercise as often as required to cover the membership fee [12].From a public health perspective, the importance of participation in physical activity has been acknowledged in public health policies and recommendations around the globe [13, 14]. To contribute to the achievement of public health goals, it is critical that sport providers provide programs that take time constraints into account and train people in how to exercise efficiently within a short period of time. The purpose of the present study is to examine how people managed to integrate a time efficient fitness program provided by gyms in Germany into their weekly activities. The program was accompanied by a survey where participants were asked to state the time they allocated to various weekly activities before and during participation in the fitness program. This study advances the following two main research questions: (1) How does the participants’ time spent on other weekly activities change when they participate in the program? And (2) what factors explain the difference in time allocated to other weekly activities?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

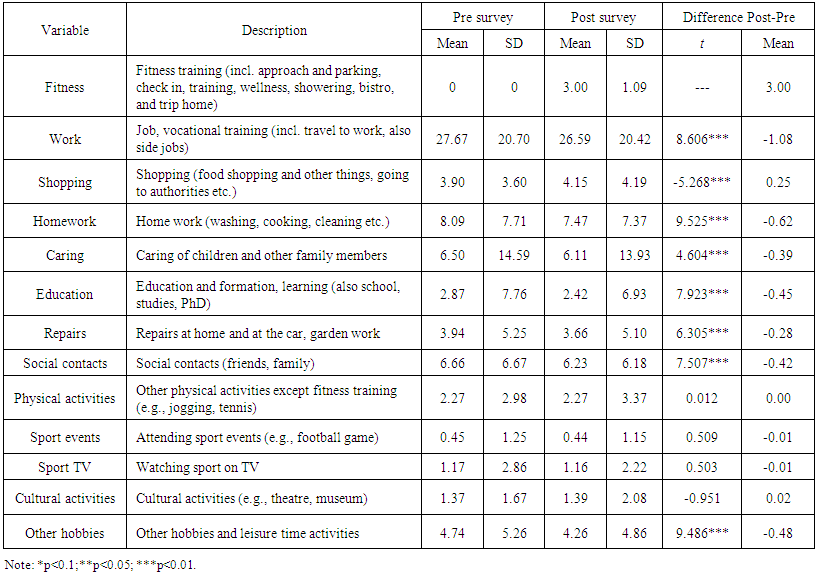

- This quasi-experimental study is part of a larger project examining the role of time and health in fitness participation [15, 16]. The project is in line with the ethical guidelines of the university leading this research. It was funded by a German fitness consultancy company. Several fitness centers across Germany are clients of this consultancy company, and 316 centers participated in the project. They registered for the project against a fee and obtained the respective marketing material as well as instructions for training and participant data management for the on-floor coaches. The test persons showed up voluntarily at these fitness centers and were informed that they can leave the program whenever they want without any disadvantages occurring. Participation in the fitness program was free of charge. The minimum age for participation in this project was 16 years. The time frame for each test person was approximately four weeks, while the overall project was completed within a period of six months (between 01.04.2013 and 01.11.2013). The study design was three-fold: (1) Physical entry test and pre survey, (2) four-week training phase, and (3) physical exit test and post survey. In the first phase, the physical entry test consisted of two strength exercises (lat. rowing and leg press) and was already applied and validated in previous research [17]. For every test person the on-floor coach chose an appropriate weight. After the entry test, the participants completed an online survey on a tablet computer. At the beginning of the survey, the coach was instructed to fill in the unchangeable club id (three digits; assigned to each fitness center by the project team) and the test person id (also three digits; assigned in ascending order by the coaches), the test person’s gender, age, height, and weight, and to note both the weight of the entry test and the number of repetitions the test person could perform with this weight. Then the tablet computer was given to the test person for the completion of the survey. This survey started with a question about the participants’ training goals which were assessed using the scale provided and validated by Sebire et al. [18]. Participants were provided with 20 statements and asked to state the importance of each training goal on a 7-point scale (from 0=not important at all to 6=very important). These statements can be summarized into five categories named social affiliation, image, health management, social recognition, and skill development [18]. For each category the mean value of the four corresponding statements was calculated. On average, the training goal of health management was considered most important to participants (M=5.12), followed by image (M=3.95), skill development (M=3.79), social affiliation (M=1.71), and social recognition (M=1.65) [16]. The questions asking for the time spent on various weekly activities were placed in the middle part of the questionnaire. Participants were asked to state how much time they usually allocate per week to work, shopping, homework, caring, education, repairs, social contacts, other physical activities, sport events, watching sport on TV, cultural activities, and other hobbies and leisure time activities (Table 1).

| Table 1. Activities before and during participation in the fitness program (in hours per week) |

2.2. Longitudinal Dataset

- A pure longitudinal sample was compiled with the help of an unchangeable personal identification number (PIN; six digits) created with the club id and the test person’s id. Altogether, a total of 21,746 test persons participated in the pre survey and 13,594 in the post survey. However, several cases had to be deleted because of drop-outs (people just clicked through, survey not/hardly completed, and implausible answers) and missing, duplicate, or incorrect PINs. After the data cleaning, 18,984 cases were left in the pre survey and 12,131 in the post survey. The datasets of the pre and post survey were matched using the PIN as the key variable. Altogether, 11,239 people participated in the pre and post survey. The plausibility of these matched pairs was checked by comparing the data on age, gender, height, and weight between the pre and the post survey. While gender had to be identical, slight differences in age (+1 year), height (±1cm), and weight (±10kg) were tolerated. As a result of these plausibility checks 758 cases were removed leading to a longitudinal sample of n=10,481 cases.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

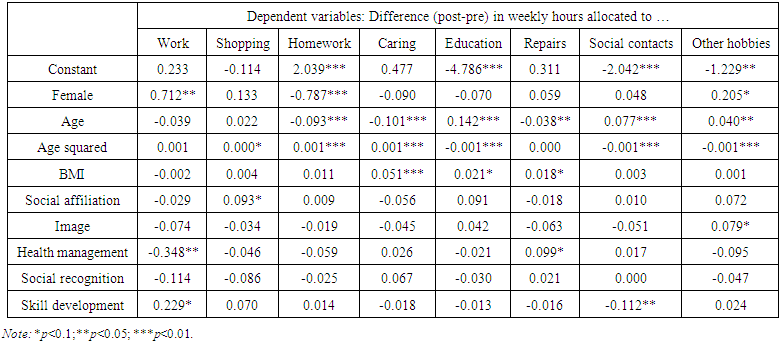

- The empirical analysis was three-fold. First, the responses on the weekly activities variables were checked for plausibility. When calculating the sum of all weekly activities, the maximum number of hours accepted was 168 (=7*24 hours), particularly for people caring for children. While it is possible to perform some of the activities simultaneously (e.g., social contacts and attending sport events), it was assumed that people also need time for other activities not listed in the survey (e.g., sleeping). If the sum of hours and combination of activities did not seem plausible, the cases were deleted leaving 10,095 observations for the analysis. A comparison between this final sample and the initial larger sample (n=18,984) revealed no significant differences for gender, income, height, and weight. A significant, but only small difference was found for age (Minitial=46.1 vs. Mfinal=46.5) and educational level (Minitial=4.19 vs. Mfinal=4.22). Second, paired-samples t-tests were used to identify significant changes in weekly activities between the period before the fitness training started and the four-week training period (first research question). Third, difference variables were computed for the weekly activity variables (see last column in Table 1). In the case of a significant difference in the t-test, a linear regression analysis was estimated with the difference in hours spent on the respective activity as the dependent variable. Gender, age, age squared (to control for non-linear effects of age), body-mass-index (BMI), and the five training goals were entered as independent variables to analyze the second research question. Educational level and income were excluded from the regression because of their correlation with the number of weekly hours allocated to learning and work, respectively. An α-level of 0.1 was used for all statistical tests.

3. Results and Discussion

- Altogether, 69.6% of the test persons were female. The average age was 46.5±15.44 years. Within the German population [20], 51.0% are female and the average age is 43.9 years. This study’s sample is, therefore, slightly older and comprised of a higher proportion of females compared with the German population. The higher share of females may be attributed to the type of physical activity, since females are more inclined towards fitness activities, while males prefer competitive sports [5, 21]. At the start of the fitness program, the test persons were 170.6±8.74 cm tall and weighed 75.7±16.33 kg resulting in a BMI of 25.90±4.73. According to the World Health Organization [22], people with a BMI≥25 are considered overweight and those with a BMI≥30 are considered obese. Following these criteria, 34.0% of the test persons were overweight and another 17.1% were obese. While obesity was found to be a barrier to physical activity in previous research [23], the proposed fitness program in this study seemed attractive to overweight and obese participants. Table 1 reports the number of weekly hours allocated to various activities before and during the four-week training period. Note that the number of hours spent on fitness training in the pre survey is zero since the test persons started fitness training within the project. On average, the test persons spent three hours per week for the two sessions in the gym. Approximately 30 to 40 minutes were used for the training itself; when the gym machines were occupied or several participants participated in the training program simultaneously, it was likely that participants needed more than 30 minutes for the training. Some participants also spent time in the wellness and bistro area of the gym (if available). The remaining minutes per visit were spent on other components of the gym visit such as approach and parking, getting changed, showering, and commuting home. The high standard deviations of the variables capturing other activities of daily living indicate that these activities vary in the studied population. The results of the t-test indicate whether there are significant differences in the time allocated to other weekly activities between the period before the fitness training and the four-week training period. On average, participants significantly reduced work-related activities by one hour. Moreover, significantly less time was spent on homework, caring for children and/or relatives, education and learning, repairs and garden work, social contacts, and other hobbies and leisure time activities. On average, the time allocated to these activities was reduced by between one and three quarters of an hour. Interestingly, the time spent on weekly activities which were related to sport and culture did not change significantly. This finding is in line with previous research suggesting that participation in physical and cultural activities are complements [24]. The results of the regression analyses are displayed in Table 2. The results show that males were more likely to reduce the time spent on work and other hobbies and leisure time activities to find time to go to the gym, while female participants were significantly more likely to reduce the time allocated to homework.

| Table 2. Factors associated with the difference in activity hours (displayed are the unstandardized regression coefficients) |

4. Conclusions

- This study adds to the literature by suggesting a fitness program of short duration that takes time constraints into account. It examines how people find time to go to the gym and integrate the program into their weekly routine. Specifically, it shows what potential weekly activities participants reduce to find time to go to the gym and what factors drive these time allocation decisions. Participants in the four-week program found time to go to the gym by slightly reducing the time allocated to several other weekly activities rather than substantially reducing the time allocated to one or two activities. The findings are relevant for policy makers and public health officials. Given the positive health effects of participation in physical activity [8], it can be recommended that such time efficient programs are supported, particularly because they seem attractive to overweight and obese people. Thus, these programs able to tackle two perceived barriers to physical activity – obesity [23] and lack of time [2]. An additional effect of participation in such a program may be that overweight and obese people become more active in their daily life which may in turn benefit their ability to participate in physical activity – eventually starting a virtuous cycle. Another argument for supporting such programs is their attractiveness to females; research shows that females living in urban areas were less active than rural females [25]. Since fitness clubs in Germany are typically located in urban areas, such programs represent an opportunity to increase activity levels among urban females. The present research has some limitations that represent directions for future research. First, it relies on people’s self-reported time spent on various activities. While asking these questions is common in official surveys [19], it is not clear to what extent people can memorize how many hours they allocated to various weekly activities. Thus, the presented figures can only be considered estimates. Second, the study is limited to participation in fitness centers. It would be interesting to examine time management when people start practicing other sport activities. Third, the fitness program was limited to a four-week period. It would be interesting to see how people continue with the program and whether the evident effects are robust in the long term.

Funding Statement

- This work was supported by INLINE consultancy, Dorsten, Germany. The funding source was not involved in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and the writing of the paper.

References

| [1] | Alexandris, K., and Carroll, B., 1997, Demographic differences in the perception of constraints on recreational sport participation: results from a study in Greece., Leisure Stud, 16(2), 107–125. |

| [2] | Reichert, F.F., Barros, S.J.D., Domingues, M.R., et al., 2007, The role of perceived barriers to engagement in leisure-time physical activity., Am J Public Health, 97(3), 515–519. |

| [3] | Humphreys, B.R., and Ruseski, J.E., 2011, An economic analysis of participation and time spent in physical activity., B E J Econom Anal Policy, 11, Article 47. |

| [4] | Rasciute, S., and Downward, P., 2010, Health or happiness? What is the impact of physical activity on the individual?, Kyklos, 63(2), 256–270. |

| [5] | Downward, P., and Riordan, J., 2007, Social interactions and the demand for sport: an economic analysis., Contemp Econ Policy, 25(4), 518–537. |

| [6] | Ruseski, J.E., Humphreys, B.R., Hallmann, K., et al., 2011, Family structure, time constraints, and sport participation., Eur Rev Aging Phys Act, 8(2), 57–66. |

| [7] | Wicker, P., Hallmann, K., Breuer, C., 2013, Analyzing the impact of sport infrastructure on sport participation using geo-coded data: Evidence from multi-level models., Sport Manag Rev, 16(1), 54–67. |

| [8] | Humphreys, B.R., McLeod, L., Ruseski, J.E., 2014, Physical activity and health outcomes: Evidence from Canada., Health Econ, 23(1), 33–54. |

| [9] | McLeod, L, Ruseski, J., 2013, Longitudinal relationship between participation in physical activity and health. [Online]. Available: http://economics.ca/2013/papers/ML0007-1.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2015. |

| [10] | Reiner, M., Niermann, C, Jekauc, D., et al., 2013, Long-term health benefits of physical activity – a systematic review of longitudinal studies., BMC Public Health, 13(1), 813–821. |

| [11] | Mullahy, J., and Robert, S.A., 2010, No time to lose: time constraints and physical activity in the production of health., Rev Econ Househ, 8, 409–432. |

| [12] | Della Vigna, M., and Malmendier, U., 2006, Paying not to go to the gym., Am Econ Rev, 96, 694–719. |

| [13] | Haskell, W.L., Lee, I., Pate, R.R., et al., 2007, Physical activity and public health – updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association., Med Sci Sports Exerc, 39, 1423–1434. |

| [14] | WHO, 2010, Global recommendations on physical activity for health. [Online]. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599979_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed January 16, 2015. |

| [15] | Wicker, P., Coates, D., Breuer, C., 2015, Physical activity and subjective well-being: the role of time., Eur J Public Health, 25(5), 864–668. |

| [16] | Wicker, P., Coates, D., Breuer, C., 2015, The effect of a four-week fitness program on satisfaction with health and life. Int J Public Health, 60(1), 41–47. |

| [17] | Boeckh-Behrens, W.U., and Buskies, W., 2007, 2 x 20 = Fit mach mit. Dokumentation und Auswertung [2 x 20 = fit join in. Documentation and analysis]. Bayreuth: Universität Bayreuth. |

| [18] | Sebire, S.J., Standage, M., Vansteenkiste, M., 2008, Development and validation of the goal content for exercise questionnaire., J Sport Exerc Psychol, 30(4), 353–377. |

| [19] | DIW (2011). Leben in Deutschland [Life in Germany]. [Online]. Available: http://www.diw.de/documents/dokumentenarchiv/17/diw_01.c.394133.de/soepfrabo_personen_2011.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2013. |

| [20] | Federal Statistical Office (2014). Bevölkerungsentwicklung [Population development]. [Online]. Available: Bevoelkerung.html. Accessed September 16, 2014. |

| [21] | Breuer, C., Hallmann, K., Wicker, P., 2011, Determinants of sport participation in different sports., Manag Leisure, 16(4), 269–286. |

| [22] | WHO (2015) Obesity and overweight. [Online]. Available: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/ fs311/en/. Accessed October 22, 2015. |

| [23] | Ball, K., Crawford, D., Owen, N., 2000, Too fat to exercise? Obesity as a barrier to physical activity., Aust N Z J Public Health, 24(3), 331–333. |

| [24] | Muniz, C., Rodriguez, P., Suarez, M.J., 2011, The allocation of time to sports and cultural activities: an analysis of individual decisions., Int J Sport Financ, 6(3), 245–264. |

| [25] | Machado-Rodrigues, A.M., Coelho-e-Silvy, M.J., Mota, J., et al., 2012, Urban–rural contrasts in fitness, physical activity, and sedentary behaviour in adolescents., Health Promot Int, 29, 118–129. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML