-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2016; 6(2): 70-75

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20160602.09

The Idea of Using Practice in Mind Training Program for Rugby Players to Improve Anxiety and Kicking Performance

Mohd Fared Yahya, Mazlan Ismail, Afizan Amer

Universiti Teknologi Mara, Selangor, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Mohd Fared Yahya, Universiti Teknologi Mara, Selangor, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

PIM training program is one of the imagery interventions employed by athletes to improve golf skills performance. This study attempted to measure the effects of Practice in Mind (PIM) training program on anxiety level and the right side of 22 meter place kick performance of rugby players. This study was a double blind experimental design research. Fifty-eight university male rugby players between the age range of 18 to 25 years old (M= 21.43, SD= 2.04) participated in this study. Participants were divided into two groups which is the intervention group (PIM group) and the control group (only physical practice). In PIM group, participants were instructed to do imagery - physical practice, meanwhile, the control group only performed physical practice for three times per week. The Mixed Between – Within Subjects found that PIM group significantly performed better as compared to control group in place kick performance, self-confidence and had higher anxiety level tolerance. Future research can be conducted to determine the effectiveness of PIM training program on skilled players and different genders or sports that have varying cognitive complexity. Research still needs to be conducted particularly in the mediating role of self-efficacy, moods, and arousal of PIM training program.

Keywords: PIM training program, Imagery training, PETTLEP, Anxiety, Rugby place kick

Cite this paper: Mohd Fared Yahya, Mazlan Ismail, Afizan Amer, The Idea of Using Practice in Mind Training Program for Rugby Players to Improve Anxiety and Kicking Performance, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 70-75. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20160602.09.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Psychological Skills Training (PST) is a comprehensive intervention package that consists of anxiety control, conflict resolution, mental imagery, concentration, self-confidence, and goal-setting that are developed to educate and train athletes in mental preparation thus helps in improving an athlete’s performance [1]. An optimal level of mental preparation prior to competitive game may help in producing a better outcome in the skill task performance [2]. This is also agreed by Hall, et al. [3] that mental skills are important building blocks for successful competitive performance. Mental imagery or imagery is defined as one of the best PST methods that requires the athletes to imagine themselves in ways that leads to learning, developing skills and routine that facilitate the performance of those skills [4].Since there were a lot of studies regarding imagery training methods, researchers have begun to expand the understanding and practical applications of imagery into a specific PIM training program that may assist in related emotions that occurs in competitive match [5-7]. PIM training program is an imagery training that explored the functions of the seven PETTLEP components which is Physical, Environment, Timing, Task, Learning, Emotion, and Perspective together with stimulus-response prepositions in a facilitative directions [5]. In a study on golf putting performance in golfers, it was found that golfers in PIM training group was superior in skills performance, self-efficacy, and moods as compared to traditional imagery practice and only physical practice [6-8]. Apparently, anxiety is one of the emotions that occurs while competing in competitive tournaments [9]. Studies have shown that athletes who can regulate their levels of anxiety to be at optimal level and have better concentration and task-oriented thoughts tend to be more successful than athletes who do not have these elements [10, 11].In sports that vigorously challenged the physical component such as rugby, an optimal level of anxiety might be one of the keys in major turnover of a match [12]. According to Woodman and Hardy [13], when anxiety are treated well, it may increase the level of self-confidence within athletes in a competition. Past study also found that rugby players had a higher in cognitive and somatic anxiety before the first game compared to the second game [14]. Since kicking is one of the options to score points in rugby, it is important to train psychological aspect apart from physical component [15]. Physical ability may become a priority when the distance is farther from the post, nevertheless it is also important to train the psychological aspect as both aspects works together to produce optimal results [16]PIM training program have been proven to improve in sport performance after six weeks of intervention [5]. Recent study conducted by [17] found that PIM training helps to improve the performance of netball shooters. To date, there is still no empirical evidence on the effectiveness of PIM training program on other sports than golf. Moreover, past study that implemented imagery particularly PIM training program did not focus on the anxiety that occurs in participants [5]. It is believed that when anxiety perceptions are not well treated during competitive performance, it may impact the outcome in competitions as high level of anxiety will pressure the athletes to perform task less efficiently [18]. Therefore there is a need to measure the effects of PIM training program on anxiety and kicking performance of rugby players.

2. Methods

- Participants: Fifty-eight university male rugby players within the age range of 18 to 25 years old (M = 21.43, SD = 2.04) participated in this study. For selection of participants, Movement Imagery Questionnaire-Revised (MIQ-R) was used to identify the level of imagery and Self-Reported Footedness was used to determine the dominant foot before beginning the intervention training program [19, 20]. Next, participants were randomly assigned to imagery-physical practice (PIM group) and only physical practice group (control group).

3. Instrumentations

- PIM imagery intervention guides: An imagery script that explored the functions of seven PETTLEP components together with stimulus-response prepositions was developed [6-8]. As suggested, facilitative direction was also established in the script [8]. Participants were required to wear proper rugby clothing (Physical component), imagine to feel the real place kick task (Emotion component), imagine from walking to the point of place kick until the kick successfully clears the goal (Timing component), participants were asked to perform consistently with an actual task (Task component), participants were to perform a place kick on an actual rugby field (Environment component) and listen to their own imagery script recorded from the voice recorder (Perspective component). Lastly, participants were advised to modify their own imagery script after each session they partook (Learning component). For each participant, the length of the audio guide was approximately not more than 2 minutes and total sessions were approximately about 30 minutes including physical practices [6, 8]. An audio aid was used since it is more practical and one of the easy tools to do imagery practices [21]. A digital voice recorder model by Sony ICD-P620 was used to record the imagery script.Place kick task performance and scoring: Ten standard competition balls (Gilbert Size 5) were provided by the researcher. Participants were asked to perform 10 trials of place kick and the scoring was categorized as 4 points if the ball successfully clears the goal post, 3 points if the ball missed under the goal post, 2 points if the ball missed to any other sides of the goal post and 1 points if the ball did not reach the goal post line. Thus, participants were awarded a total score out of the maximum of 40 points.Twenty-two (22) meter distance: Statistics revealed that place kicks on right side of the field recorded less success rate which was 46% as compared to left side of the field and midline of the goal post which was 56% and 100% respectively. In respective to this, it was believed that narrow angle and farther distance make the kickers hard to deliver the points in place kick for example, 22 meter distance near the sideline of the field [23]. Anxiety: Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2R) Questionnaire was used in this study [24]. Participants rated on a 17 items consists of somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety and self-confidence with a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). CSAI-2R has been reported to have sufficient internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) with acceptable range of .81 and .84 [25, 26]. In the present study, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was acceptable at .77.

4. Procedures

- Athletes were approached prior to their regular training sessions after getting permission from the coach. Following this, participants who volunteered to participate in the study were introduced to the MIQ-R and Self-Reported Footedness Questionnaires as a preliminary analyses to ensure that participants have the same imagery ability and use right leg as a dominant leg. Subsequently, participants were divided into two groups which were imagery-physical practice (PIM group) and only physical practice (Control group). Next, participants were asked to perform the pre-test 10 trials of place kick at 22 meter distance on the right side of the field and completed the CSAI-2R Questionnaire to measure the anxiety level. In PIM group, participants were instructed to do imagery - physical practice for three times per week. Participants were advised to make some changes accordingly based on their preferences to perform the place kick. Participants listen to their imagery script from a voice recorder and perform 10 trials of place kick at 22 meter distance on the right side of the field. The control group was instructed to perform only physical practice (10 trials of place kick at 22 meter distance) for three times per week. Both groups were monitored by researchers and coaches throughout the training sessions. The post-test was conducted after the six weeks of intervention training program. Mixed Between-Within ANOVA was used to compare the mean scores on the dependent variables which is place kick performance, somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety and self-confidence between PIM group and control group.

5. Results

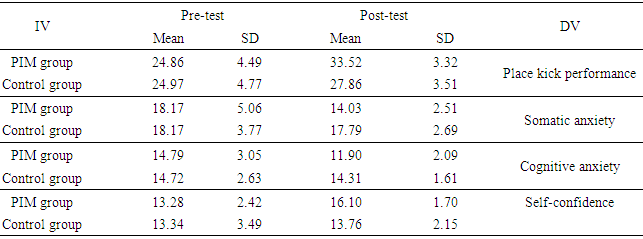

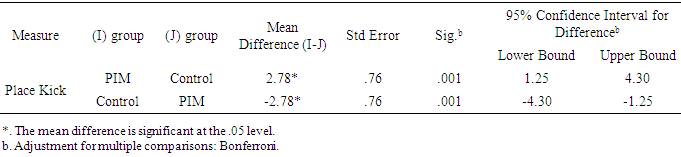

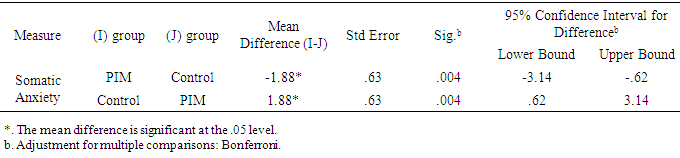

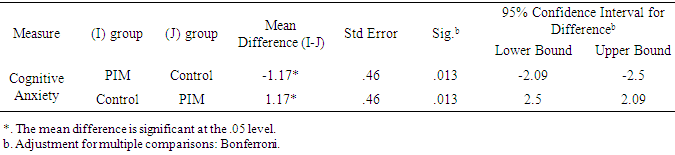

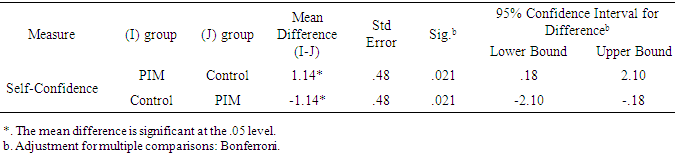

- Preliminary assumptions testing was conducted and the results showed that the data were normally distributed. A Mixed Between-Within ANOVA analysis was used to compare the scores for place kick performance, somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety and self-confidence on pre to post-test and scores between PIM and control group. Table 1 below shows the descriptive data of the participants followed by pairwise comparison in Table 2, 3, 4 and 5.

|

|

|

|

|

6. Discussions

- The results of the present study shows that PIM training program helps to improve place kick performance, self-confidence and tolerance with anxiety levels. Post-test results revealed that PIM group scores higher in place kick performance, and self-confidence as compared to control group. In addition, PIM group scores also marked a significantly decrease in somatic anxiety and cognitive anxiety thus indicated that participants are able to control the level of anxiety while performing a skill task. This findings was consistent with the previous studies [25, 27]. It was believed that with the presence of functional equivalence of PETTLEP components such as proper rugby clothing, proper execution time of skill task, and ability to deal with emotions when performing skill task [6, 8]. Given such imagery scripts that contained a stimulus-response prepositions and PETTLEP model approach that requires the participants to imagine routine cognitively and kinesthetically, it helps the athletes to focus on and performing better movement pattern that makes sense to the actual performance. Apart from that, by imagine the routine kinesthetically, athletes were also able to increase their level of self-confidence. Interestingly, an example of imagery scripts that guided the athletes to acquire the right steps, recalled the sensations and feelings when throwing the ball into basket and correct the body technique helps to regulate the anxiety thought and negative feelings that occur from the competition’s environment, subsequently boost the self-confidence [28]. Individualized engagement in training by coaches towards PIM group was believed to influence such significant results rather than practicing individual imagery scripts by self. With this, the coaches monitored and provided an additional cues or information feedback in order to correct and maximize the movements or positions required for a particular task specifically in place kick. The results of the study also supported that audio imagery used in this present study was one of the effective tools to aid in imagery practice provide a similar perspective as script reading [5].The results of the study also shows that control group improved in place kick performance and self-confidence and able to tolerate with anxiety from pre to post-test. Although participants in control groups did not practice an imagery training, it was believed that the regular practice in kicking helps the participants to distinguish the disruption of the physical task because the participants starts to adapt with the particular environment such as weather, technical execution, social environment of fans, coaches and spectators. This factors also helps the participants to build up their level of confidence from time to time. Regardless of the superlative in self-confidence, the ability of the athletes to perform at its best are still dependent upon how the athletes treat their level of anxiety. Optimal level of anxiety was believed to contributed to supreme level of self-confidence as stated in Individual Zones of Optimal Functioning theory [29].

7. Conclusions

- To conclude, the present study has indicated that PIM training program is one of the imagery training program that athletes or coaches can employ to improve sports performance and overcome the anxiety problems. A higher ability to precisely kick at goal in rugby and optimal level of psychological ability that was developed through PIM training program increased the chances of success in kicking despite in various situations especially under pressure. Athletes that experiences arousal or anxiety intolerance can benefit from PIM training program to control their level of arousal of anxiety. In addition, PIM training program also can be used during pre-season in order to optimize the sports performance prior to competitive phase. Last but not least, coaches may design a systematic psychological training program specifically in imagery aspect based on the needs of the current demands in a particular sports. Since this study were conducted on the right side of the fields, it is recommended that future study to be conducted on the left side of the field and considering to use both dominant and non-dominant legs. Future studies also should be conducted on others psychological factors such as self-efficacy, moods, and arousal that may benefit from PIM training program.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML