-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2016; 6(2): 27-31

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20160602.02

Personality and Aggression Compared between Sportsman and Non-Sportsmen in Erzurum Province

Saeed Shokoufeh, S. Erim Erhan

Atatürk University Physical Education and Sports Vocational School, Turkey, Erzurum

Correspondence to: Saeed Shokoufeh, Atatürk University Physical Education and Sports Vocational School, Turkey, Erzurum.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

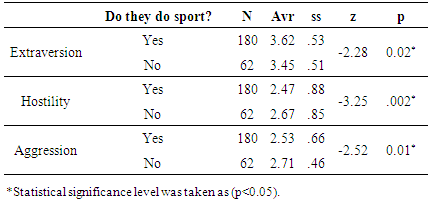

This study has been carried out in Erzurum with the aim of comparing the personalities and levels of aggressiveness of individuals who are interested in different branches of sport and of those who are not doing any sports. A sample survey was applied to 242 people, all men: 180 sportsman (volleyball, football, karate, box, tennis, basketball, curling, ice-hockey and wrestler) and 62 people who do not do any sports. In the age group 16 to 28 years, 74 percent of participants were sportsman and 26 percent were non-sportsmen. Participants completed the NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO-FFI) and the Aggression Scale (BPAQ). The results indicated that the individuals who do sports scored significantly higher on extraversion than non- athletes. The non- athletes scored significantly higher on hostility and aggression than did the individuals who do sports. There is no significant difference was found between the two groups on openness to experience, physical aggression and verbal aggression. It can be concluded that the individuals who do sports are more extroverted and have fewer aggressive attitudes compared with non- athletes.

Keywords: Sports, Psychology, Personality, Personality scale, Aggressiveness, Aggression scale

Cite this paper: Saeed Shokoufeh, S. Erim Erhan, Personality and Aggression Compared between Sportsman and Non-Sportsmen in Erzurum Province, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 27-31. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20160602.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Personality is the set of psychological traits and mechanisms within the individual that are organized and relatively enduring and that influence his or her interactions with, and adaptations to, the intrapsychic, physical, and social environments [1]. Personality structure has explained based on different models. Three-dimensional model of personality including dimensions of extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism [2]; and five factor model of personality including dimensions of neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness two that have supported both theoretical and empirical by a large number of researchers in the last decades [3]. Aggression is operationally defined as an intentional physically or psychologically harmful behavior that is directed at another living organism [4]. Based on the BDHI, Buss and Perry redefined it toimprove its psychometrical properties, and the result was the Aggression Questionnaire (AQ), which measures four aspects of aggression: Physical Aggression and Verbal Aggression, which involve hurting or harming others, represent the instrumental or motor component of behaviour; Hostility, which consists of feelings of ill-will and injustice, represents the cognitive component of behaviour; and Anger, which involves physiological arousal and preparation for aggression, represents the emotional or affective component of behaviour [5].The recent studies investigating personalities of sportsmen concentrate on the topic of “personality” and “aggressiveness”. In this context, studies comparing the personal qualities and levels of aggressiveness of sportsmen with those of individuals who do not do any sports have underlined significant differences. In a study done by Tiryaki and his colleagues, the researchers found out’ that those who do sports are more extroverted and psychologically-balanced than those who do not [6]. As a result, sportive activities that are performed either professionally or as an amateur are important tools to control an individual in various aspects, to fulfill his/her deficiencies, to use his/her positive sides for a meaningful activity and to develop his/her personality. This study has been carried out to compare and contrast the personalities and levels of aggressiveness of those who do sports and of those who do not. Within the framework of the study, the personalities and levels of aggressiveness of the participants were analysed regarding the different socio-demographic qualities; and the accuracy of some hypotheses have been researched.

2. Tools and Methods

2.1. Research Group

- The scope of the study was composed of those who do different types of sports and those who do not do any sports in Erzurum. The sampling method of the study has been composed by random sampling method. The sampling included 242 people, all men; 20 volleyball players, 20 football players, 20 karateka, 20 boxers, 20 tennis players, 20 basketball players, 20 curling players, 20 ice-hockey players, 20 wrestlers and 62 people who do not do any sports. In the age group 16 to 28 years, 74 percent of participants were sportsman and 26 percent were non-sportsmen.

2.2. Data Collection Tools

- The data collection tool used in the study is a questionnaire form composed of three parts. After the researcher had an interview with the relative teachers of the teams doing the survey and obtained essential permissions, he went to different locations and gyms between April 1 and April 30, 2014, in Erzurum (Turkey) and helped individuals to answer the questions rigorously after explaining the survey to them. The demographic information regarding the participants was in the first part. In the second part, we used the Aggression Scale, which was improved by Buss and Perry and translated into Turkish by doing the reliability study by H. Andaç Demirtaş in 2012, was used [7]. The survey was carried out in the form of a five-point Likert scale. It aims to measure four different extents of aggression such as physical aggression, verbal aggression, hostility and anger. The physical aggression subscale includes nine questions related to physically harming somebody; the verbal aggression subscale includes five questions related to harming somebody verbally; the anger subscale includes seven questions aiming to measure aggression emotionally; the hostility subscale includes eight questions aiming to measure aggression cognitively. In this survey, the internal consistency of the aggression questionnaire was found to be 0.819.In the third part, we used the Personality Scale, which was improved by Costa and McCrae and translated into Turkish after the reliability study by Sami Gülgöz [8]. The survey was carried out in the form of a five-point Likert scale. The Turkish version of the survey is a five-point Likert scale composed of 60 items in total. It aimed to measure five different extents of personality such as extraversion, openness to experience, neuroticism, agreeableness and conscientiousness. The extraversion subscale includes 12 questions; the openness to experience subscale includes 12 questions; the neuroticism subscale includes 12 questions; the agreeableness subscale includes 12 questions; and the conscientiousness subscale includes 12 questions. In this study, the internal consistency of the personality survey is 0.879.

2.3. Analysis of Data

- We carried out various statistical analyses on the data acquired from the participants by using the IBM SPSS Statistics v20.0 program. We carried out the Shapiro–Wilk test in order to test whether the participants were appropriate to normal distribution or not, and non-parametric tests were carried out because they were inappropriate to normal distribution. The Kruskall–Wallis test was carried out in order to compare averages of the personality and aggression sub-dimension with age factor. One of the non-parametric tests called the Mann–Whitney U test was carried out in order to determine the differences between participants who do sports and those who do not do sports and individuals’ personality and aggression sub-dimension averages. Finally, the Spearman correlation analysis was carried out in order to determine the relationship between the participants’ personality and aggression sub-dimension. In the analysis, the statistical significance level was taken as (p<0.05).

3. Results

- According to table 1 there are significant differences between the sub-dimensions of personality and aggression of people who do sports.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

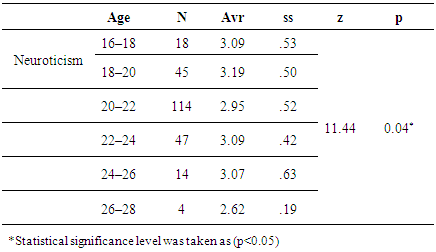

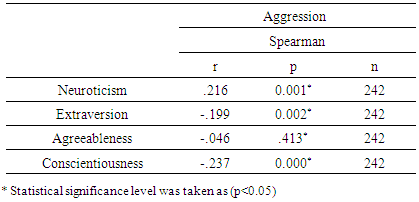

- In research on the related literature, many studies carried out on sports, personality and aggression have been found sub dimensions. These studies have shown that sport has an important effect on personality and aggression levels. Besides, according to the results of many studies, we have seen that sport does not only positively affect individual development but also decreases levels of aggression and other negative feelings. As a socializing tool for an individual, sport also gives the subject a chance to express his/her emotions and to realize himself/herself as a result of the activities and games involved in the sports. An individual gets rid of his/her tendency to aggressiveness and learns to control himself/herself [9]. In the study, we have seen that the aggressiveness (2.71±0.46) and hostility (2.35±0.67) sub-dimensions of the participants who do not do sports are the highest, while those doing sports hold the highest point (3.62±0.53) in terms of the sub-dimension of extraversion. Sports enables individuals to express their emotions and to realize themselves thanks to the motions and games involved in it. Thanks to the sports, people learn how to control their instinct of aggression and many negative motives. In addition to becoming socialized as they meet different people, they become more self-confident by learning how to do physically difficult actions. In the end, individuals become more lively and get more life pleasure. Moreover, starting sports training in elementary school ages contributes to the development of the society impressively. Scientists, examining the relation between sports and characteristics, have established that the sports plays an important role in the course of people’s socialization and the characteristic development. In their study, Newman and Cooper compared people who do sports and those who do not in terms of characteristics, and detected that people who do sports are more dynamic, self-controlled, extraverted and easy going than those who do not [10]. A study conducted by Tiryaki and his colleagues has shown that people who do sports are extraverted and psychologically balanced when compared with those who do not [11]. Individuals engaged in sports for a long time are very cheerful, have leadership qualities in their social environments and are less prone to inferiority complex, less angry and more active. Alp and Eraslan determined that the levels of aggressiveness of the children doing sports regularly decrease in their study analysing the levels of aggressiveness of children doing sports and children not doing sports in line with their socio-demographic background [12].These findings support the study. We can conclude that while a person spends time doing sport, many of his/her abilities like socializing and sharing are developing. The reason for low levels of aggressiveness among those doing sports is that they get rid of their instinct for violence while doing sport. Thus, those doing sports are less prone to violence than those who do not do any sports. Among different age levels, participants in the 18–20 age range (3.19±0.50) and the 16–18 age range (3.09±0.42) are the most emotionally imbalanced group according to their average points.Neuroticism means an instable situation related to one’s mostly negative feelings. Since puberty is a transition period, an adolescent’s emotional status is not stable. Since his/her emotional status is not clear, an adolescent’s emotional imbalance does not show any relation to self-esteem. On the other hand, openness to experience is positively related to self-esteem. Adolescents that are open to experience are imaginative, curious, original, broad-minded, more creative and independent [13].At the end of their study named “Sport, puberty and neuroticism, Godwin and his colleagues found that levels of neuroticism are the highest among adolescent men. These findings support the results of this study [14].Some meaningful relations with the total average levels of aggressiveness and emotional imbalance were found, while there is an inverse relation with the levels of extraversion and compatability. The emotional imbalance dimension is directly related to the level of aggressiveness, but there is no meaningful link with aggressiveness and compatability. In other words, according to the table, when the total points of aggressiveness increase, there appears an increase in emotional imbalance; yet, a decrease is clear in terms of the extraversion, liability and compatability dimensions.In a study by McCullough and his colleagues, a direct link has been determined between neuroticism, rage and hostility, while a reverse link is apparent in terms of liability and compatability sub-dimensions [15]. Sharpe and Desaihave observed in their study that there is a direct link between neuroticism, rage and hostility; yet, extraversion, conscientiousness and agreeableness are adversely affected by neuroticism [16]. In a study conducted by Anderson, aggressive behaviour adversely affects liability and compatability [17].Christopher and his colleagues, in a study on the relation between personal traits and aggressive behaviours, claim that conscientiousness and agreeableness decrease while aggressiveness increases and determine that neuroticism is directly related to physical aggressiveness [18]. Gallo and Smith stress that there is a positive relation between extraversion and physical aggressiveness. The aforesaid studies support this study [19].No matter how described, aggression is the activity of people’s damaging both themselves and others around them and expresses a negative social skill which is not approved. It can be accepted that every individual bears this negative social skill more or less. However, it can be said that the physical education and sports are important in eradicating or at least reduce this negative skill and they need to be supported with preventive activities especially during adolescence period in which social development is experienced at the peak level [20]. In a study, it was observed that there was a reduction in the emotions of tension, aggression, depression and hostility right after a jogging and weight lifting session. Nevertheless, no changes were observed in these variants after a karate session. It was reported that the intensity of exercises performed by karate players in the study was lower than the intensity of exercises performed by other groups [21].In a study carried out by Istanbul Provincial Directorate of National Education, it was reported that the violence in schools declined by 80 % thanks to a series of precautions and sports and increasing the number of social activities are among these precautions [22].In parallel to this study, it can be stated that individuals not doing sport have higher levels of rage and hostility when compared with those doing sport; those doing sport are more extraverted than those not doing sport; the 16–18 age group have higher levels of neuroticism, while levels of aggressiveness and neuroticism are lower among responsible, extraverted individuals. When later studies and existent literature and the results of this study are scrutinized, we can suggest that new studies could be done through different methodologies and samplings.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML