-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2015; 5(4): 145-150

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20150504.05

Contribution to the Identification of the Professional Skills Profile of Coaches in the Algerian Sport Judo System

Belkadi Adel1, Benbernou Othman1, Sebbane Mohamed1, Laroua Abdelhafid1, Benkazdali H. M1, Jaques Gleyse2

1Research Laboratory Optimization of Programs in Physical and Sporting Activity Institute of Physical Education and Sport University of Mostaganem Algeria

2Interdisciplinary Laboratory of Research in Teaching, Education and Training (LIRDEF) Faculty of Education - University of Montpellier 2 France

Correspondence to: Belkadi Adel, Research Laboratory Optimization of Programs in Physical and Sporting Activity Institute of Physical Education and Sport University of Mostaganem Algeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study was designed to determine the professional skills of coaches, which are identified and judged based on a large number of factors. The purpose of this article is to describe the views of four groups of professional actors concerning coaches’ skills: athletes, coaches, leaders and experts from the Algerian judo sport system. The actors of the system responded to the same series of questions regarding coaches’ skills. The actors’ views across the five groups of specific professional skills are more similar than dissimilar, with each professional group emphasizing a different item of the coaches’ skills. The results show that coaches and athletes have the same representations of technical and teaching skills. However, there is a discrepancy in representations regarding organizational and managerial skills. Stakeholders’ views are compared to the coaching science literature, and recommendations for developing a professional skills repository of judo coaches are provided.

Keywords: Identification, Professional Skills, Profile, Coaches

Cite this paper: Belkadi Adel, Benbernou Othman, Sebbane Mohamed, Laroua Abdelhafid, Benkazdali H. M, Jaques Gleyse, Contribution to the Identification of the Professional Skills Profile of Coaches in the Algerian Sport Judo System, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 145-150. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20150504.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- If a coach who is involved in a high-level sport claims to have (or should have) a high level of skills, the nature of these skills and the conditions that favour their acquisition must be specified (Zarifian, 1995). The conditions are not simple and thus raise questions, especially concerning the implementation of the training of coaches and the transmission of their knowledge.In fact, many "very good" current coaches (recognized as experts by their peers) had no initial training that led them to these functions. (Ragni, 1996) noted the same phenomenon in athletics, where more than half of the high-level coaches do not have a certificate of sport coach. According to this author, in terms of the expertise of coaches, the guarantee conferred by the possession of knowledge or qualifications is insufficient. Indeed, in interviews that were conducted to establish a record of the Olympic experience of coaches of different sports disciplines in 2012, most coaches emphasized their experience as an athlete, their knowledge of the environment, and teaching that is primarily realized through training, rather than through theoretical knowledge from books. The recruitment of the coaches of Olympic teams (the highest level of sports competition) is performed without consideration of the coaches’ level of training according to a recognized certification in the field. Theoretical models of training processes are based on scientific and technical rationalization of the training and the approach of the coach, as addressed by training or presented in books (Weineck 1990; revues Helal, 1986). With respect to sports training, coaches generally perceive the theoretical models as being out of touch with their practice and inadequate for organizing their work. This is not limited to the training of Algerian coaches. Indeed, in an article on the expert knowledge structure of coaches, Salmela (1994) reported that American research shows that only 46% of coaches think that there are weak principles, theories and designs in the Judo field. In addition, he stated that coaches consider the training of trainers (coaching classes) and books on training (coaching books) to be resources with little importance (Salmela, 1994). Sports coaches who work with high-level athletes are often considered "professional" experts in the sports milieu. We often claim that they have a high level of skill in varied registers (Danvers, 1992). Many authors present coaches as "engineers" of performance (Helal, 1986; Platonov, 1988 Weineck, 1990), educators, pedagogues (Piéron, 1992), psychologists (Partington, 1988), and managers (Bosc.G, 1983).The aim of the present study is to construct the notion of professional competence in reference to the executives of the educational literature, especially (Mialaret 1979, Cardinet 1988, Gillet 1991). These skills are analysed according to two distinct dimensions:1 / specific skills that allow "Within a family of situations identifying a task problem and its resolution by an effective action performance (Gillet, 1991).2 / classes of business situations that characterize the families of tasks that are related to the functions of their coach. We distinguish the coaches’ skills and knowledge; As well as research of training sports (Malglaive 1990; Delbos & Jorion, 1998; Levy Leboyer, 1997). But the list should not be a separate ‘laundry’ list of knowledge, skills, and attitudes (and/or attributes) As is done in one-dimensional frameworks of competence (Segalas, Ferrer-Balas, Svanstrom, Lundqvist and Mulder, 2009), because these detailed lists cannot provide guidelines for curriculum/program development (Barnett, 1994). Indeed, one-dimensional perspectives are given way to multi-dimensional approaches of competence (Johsua S. 1996), which considers knowledge, skills, and attitudes as dimensions of competence (Le Deist & Winterton, 2005). Competence in this respect is defined as an integrated performance-oriented capability of a person to reach specific achievements, in which ‘integrated’ refers to a cohesive complex of knowledge, skills, and attitude and the integration with the context in which successful performance has to take place (Mulder, 2011).

2. Methods and Means

2.1. Participants

- This study was performed during the 2014-2015 sporting season. A total of 330 subjects (225 athletes, 45 coaches, 35 leaders and 25 experts from the judo field) voluntarily participated in this study.

2.2. Materials and Procedure

2.2.1. The Questionnaire

- An analytical model of coaches’ skills included five groups of specific skills (technical, educational, relational, organizer and manager and managerial skills) and four groups of professional situations (design and preparation of the training, performance of training (and track competitions), organization and management, and institutional and relationship situations).The questionnaire was administered via the Internet (online). A total of 205 (approximately 62.12%) of the 330 (100%) questionnaires were usable from a statistical point of view.The analysis model, which was briefly presented above, was the basis for the construction of a survey questionnaire. The questionnaire combined closed questions for a quantitative treatment of responses and spaces for free comment for a possible future qualitative analysis.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- The coding scheme is designed to facilitate data entry using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) Version 22. The study of response differences between groups was performed using the Chi squared test.

3. Results

- The results of the quantitative analysis supported the two hypotheses of the study. With regard to the first hypothesis, the study limitations prompt us to recommend extreme caution in interpreting the results: we claim to identify only trends that emphasize and strengthen the initial hypothesis.

3.1. Specific Skills

3.1.1. Analysis of Choice and Non-Choice Skills / Coach Profile

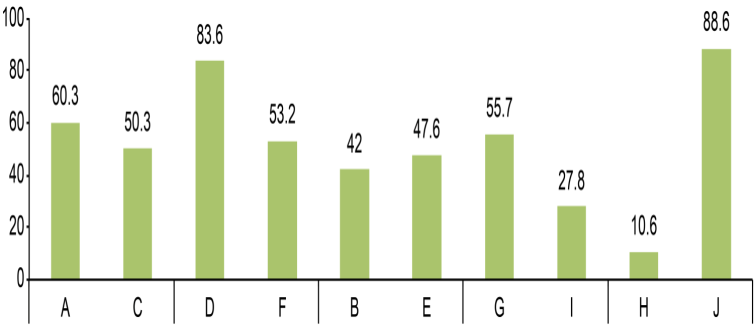

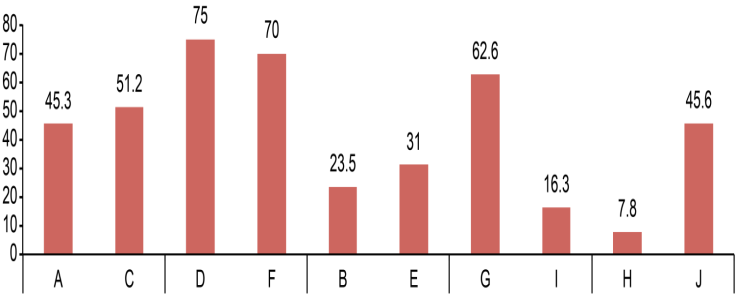

- Technical Skills:Item A: Amount of training at the optimum level for athletes.Item C: Having expert knowledge of the competition. Teaching Skills:Item D: Be a good teacher, able to facilitate engaging training sessions to clearly explain and convey his analyses.Item F: Become effectively involved with each athlete during the training sessions.Relational Skills:Item B: Having a strong personal investment in his work (Get involved without mattering).Item E: Having psychologist qualities, allowing the athlete to confide his personal problems.Organizer and Manager Skills:Item G: Be a strict and effective organizer regarding logistics for training and travel.Item I: Be a good manager of the team's funds.Managerial, Animation and Team Management Skills:Item H: Represent and defend the interests of the team and discipline in federal bodies.Item J: Ability to discuss the choices and the important decisions concerning the operation of the team with the athletes.

4. Discussion

- The observed frequencies, as expressed in percentages, after grouping responses from various categories of stakeholders on the 15 modalities (choice) and non-response (non-choice) are shown below.

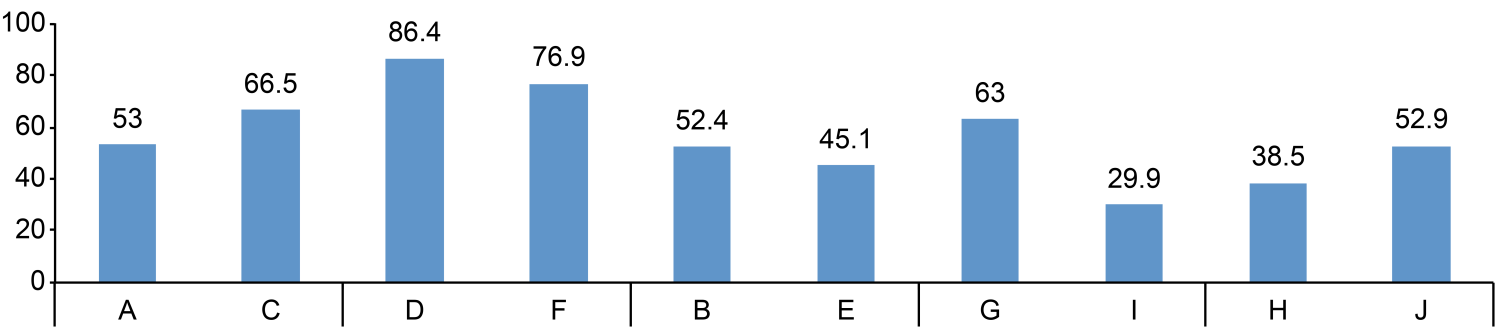

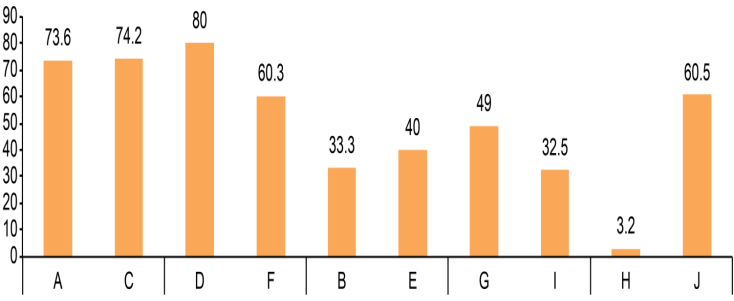

4.1. The Choice of Skills in the Constitution of the Coach’s Profile

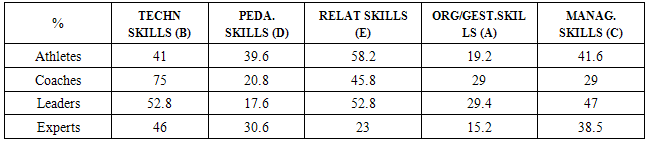

| Figure 1. Results of the selection of skills in building the profile of the coach according to the Athletes |

| Figure 2. Results of the selection of skills in building the profile of the coach according to the coaches |

| Figure 3. Results of the selection of skills in building the profile of the coach according to the leaders |

| Figure 4. Results of the selection of skills in building the profile of the coach according to the experts |

4.2. Test Application of Chi Squared (Chi squared)

4.2.1. Comparison of Choices / Non-Choice for Each Set of Skills

- The Chi squared test allows us to answer the question of whether the differences in choice of athletes / coaches / managers / experts as highlighted in the charts presented above, are significant.Technical Skills:Item A: Chi squared: 5.29, indicating a non significant difference between these 4 categories, with 3 degrees of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 7.81). However, the comparison AT / ENT results in a Chi squared value of 4.80, indicating a significant difference between the two categories (p<.05 threshold = 3.84 per 1 degree of freedom). The athletes value these skills less than coaches.Item C: Chi squared: 3.33, indicating no significant difference between these 3 categories, with 2 degrees of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 5.99). However, the difference observed between ENT and DIR is significant at (p<.01) (Chi squared: 3.34, p<.01, threshold = 2.7 for 1 degree of freedom). These results indicate a tendency for coaches to exploit this expertise as leaders.Educational Skills:Item D: Chi squared: 0.26, indicating no significant difference between these two categories, with one degree of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 3.84). The percentages of the responses of the four categories for these skills show that the various stakeholders agree about the importance of educational skills, as they are the most valued of all proposed skills.Item F: Chi squared: 3.45, indicating no significant difference between these 3 categories, with 2 degrees of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 5.99).Relational Skills:Item B: Chi squared: 0.70, indicating no significant difference between these 3 categories, with 2 degrees of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 5.99).Organizer and Manager Skills:Item G: Chi squared: 0.54, indicating a non significant difference between these 4 categories, with 3 degrees of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 7.81).Item I: Organizer and management skills were selected by a very small percentage of participants. This result indicates that the different actors agree on the low valuation of these skills.Managerial Skills:Item H: the Chi squared is not valid here given the low observed frequency (less than 2) of these skills being selected among three categories of actors.As in the case of the previous skills, the different actors agree on the low valuation of these skills.Item J: Chi squared: 0.56, indicating no significant difference between these two categories, with one degree of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 3.84).Analysis of the choice of prioritised skills / coach profile:Tech Skills:Item B: accurately analyse the performance of athletes and know the technical solutions.Teaching Skills:Item D: vary the training situations and know how to adapt them if necessary.Relational Skills:Item E: listen to athletes, seek out knowledge and understand them.Organizer and Manager Skills:Item A: adopt strict principles of material organization and time management.Managerial, Animation and Team Management Skills:Item C: generate knowledge and take into account the views of athletes prior to making important decisions for the team.

4.3. Results of the Prioritised Skills in the Coach’s Profile

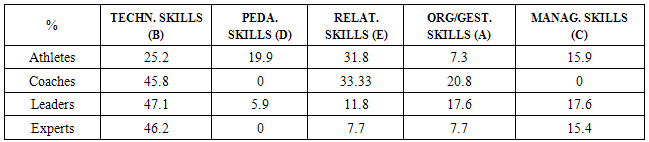

- The observed frequencies, expressed as percentages, after grouping the responses of various categories of stakeholders concerning the first two sets of skills the skills that were identified as most important) are presented below.

4.3.1. Test Application of Chi Squared

4.3.1.1. Comparison of Top Choices for Each Category

- Chi squared: 9.91, indicating a significant difference between these 4 categories, with 3 degrees of freedom, and the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 7.81). The coaches value these skills significantly more than other groups. The largest difference is between the coaches (75%) and athletes (41%), indicating that the two groups disagree on the importance of technical skills.Teaching Skills (D):Chi squared: 3.16, indicating no significant difference between these two categories, with 1 degree of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 3.84). However, this difference is significant at p<.01 (threshold = 2.70). This result reflects a tendency for athletes to exploit the instructional skills of coaches.Relational Skills (E):Chi squared 1.38, indicating no significant difference between these 3 categories, with 2 degrees of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 5.99).Organizer and Management Skills (A):Chi squared: 1.94, indicating no significant difference between these 3 categories, with 2 degrees of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 5.99).Managerial Skills (C):Chi squared: 1.69, indicating no significant difference between these 4 categories, with 3 degrees of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 7.81).Analysis of first choice: comparative representation:The most significant differences are between the athletes’ and coaches’ ratings of technical and pedagogical skills.

4.4. The Choice Analysis for the Most Important Set of Skills

- The results below are expressed as percentages of the observed frequencies for modality 1: the area of competence that is considered as the most important of the five proposed areas.

4.4.1. Test Application of Chi Squared Comparison of Top Choices for Each Category

- Technical Competence (B):Chi squared: 4.38, indicating a significant difference between these two categories for 1 degree of freedom at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 3.84). This confirms that the coaches value the technical skills significantly more than athletes. Teaching Skills (D):The test was not performed because none of the coaches choose these skills as the most important area of competence; unlike athletes, as 19.9% rank these skills as the most important of the five proposed sets of skills.

|

|

- This reinforces the idea that athletes and coaches disagree on the importance of teaching skills.Relational Competence (E):Chi squared: 2.27, indicating no significant difference between these two categories, with 1 degree of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 3.84).Organizer and Management Skills (A):Chi squared: 5.19, indicating a significant difference between these two categories, with 1 degree of freedom, at the p<.05 threshold (p<.05 threshold = 3.84); 20% of coaches report that these skills are the most important of the five sets of skills proposed.Managerial Skills (C):Concerning these skills, the Chi squared test was not used for comparison because none of the coaches select these skills as the most important area of competence; unlike athletes, as 16% rank this area of competence as the most important of the five suggested areas.

4.4.1.1. Analysis of the Number One Set of Skills: Comparative Representation

- The most significant differences are in the comparison of the ratings of ATH / COA concerning technical and pedagogical skills.

5. Conclusions

- The points of convergence and divergence between the various actors:Here, we will analyse the similarities and differences between athletes and coaches, as these groups are the most numerous and maintain the most important relationships among the groups (Wiek, Withycombe, & Redman, 2011).Consensus: the coach is a "field specialist" who is in direct contact with athletes (Leveque, 1992).There seems to be a broad consensus among athletes and coaches in the valuation of certain skills and tasks. For example, the majority of the study population stated that it is essential for the coach to be a reliable "outsider" and “target" who is able to observe and analyse performance (Hameline, 1979). The coach must also be a good teacher who is able to animate the sessions, conduct interesting training sessions, explain and clearly convey his analysis by presenting the methods, and rigorously organize and run these sessions. Finally, it is widely expected that coaches treat all members of the team equally and understand and listen to the athletes which was noted by (Le Boterf G., 2000). The tasks that are considered to be the most important reinforce this competency profile. The tasks of designing and conducting trainings are overwhelmingly the most important tasks (Johsua S. 1994).According to the results, it is less important for a coach to have a high level of skill in the areas of management (Lévy Leboyer, 1997), organization and management or institutional relations (Jolis 1997).This agreement resulted in a "classical" representation of the coach: an expert and educator technician who performs business in direct contact with athletes and focuses on optimizing the performance of athletes.However, a closer analysis of the results shows significant differences between athletes and coaches. Specifically, these groups disagree about the importance of a coach’s skills as a technician/educator (Partignton, 1988).Coaches value technical knowledge more than the athletes (Chauvier 1988). Coaches and athletes stated that the most important skills for coaches are knowing how to perform the training at the optimum level and knowing "the advanced technical solutions."Conversely, skills such as varying training situations (Boterf G., 2004) based on the athletes’ situations and external conditions and individualizing the training are more valued by athletes than by coaches.This disagreement is confirmed at the level of the coach tasks (Delbos G. & P. Jorion, 1985). Athletes favour training and driving tasks, whereas the coaches rate the design tasks as having the greatest importance. In short, beyond the consensus, coaches feel that they must first be experts and technicians (Lichtenberger, 2003) because athletes desire good pedagogues (without underestimating technical skills).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML