-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2015; 5(2): 87-92

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20150502.07

An Examination of Coping with Career Ending Injuries: An NCAA Division I and NCAA Division III Comparison

Hayley Marks1, Daniel R. Czech1, Brandonn S. Harris1, Trey Burdette1, David D. Biber2

1Department of Health and Kinesiology, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, United States

2Department of Kinesiology and Health, Georgia State University, Atlanta, United States

Correspondence to: David D. Biber, Department of Kinesiology and Health, Georgia State University, Atlanta, United States.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of this study is to qualitatively examine and compare the coping strategies and injury impact of NCAA Division I and III athletes who have sustained a career ending injury. Data was analyzed using a 4-step phenomenological method. Emerging themes were a) emotional response to injury, b) redefining identity, c) adopting a coping strategy, and d) feelings of unpreparedness to cope with transition. NCAA Division I athletes experienced more negative emotions than Division III athletes. All NCAA athletes adopted strategies to cope with the transition out of sport. The majority of participants felt unprepared to cope with this transition.

Keywords: Sport Psychology, Injuries, Coping, Athletic Identities, Transitions

Cite this paper: Hayley Marks, Daniel R. Czech, Brandonn S. Harris, Trey Burdette, David D. Biber, An Examination of Coping with Career Ending Injuries: An NCAA Division I and NCAA Division III Comparison, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 87-92. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20150502.07.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Research has shown that nearly half of college athletes report experiencing an injury during their collegiate sport career [1]. Nearly 15% of athletes retire due to a career ending injury [2]. Sport injury can be considered an unanticipated transition out of sport in which the individual’s career as a competitive athlete comes to an abrupt and unexpected halt [3]. Van Raalte and Anderson (2007) found that athletes who experience unanticipated transition due to injury, have problems in developmental areas such as academics, relationships, and vocational exploration [4]. One of the biggest problem areas for athletes after an injury is coping with the transition to life away from sport. Coping is defined as “a process of constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific internal demands or conflicts appraised as taxing or exceeding one’s resources” [5]. In other words, coping is how an individual deals with a stressful situation. One reason why a career ending injury can be so difficult to cope with is because college athletes often find their identity in their sport. Athletic identity is defined as “the degree to which an individual identifies with the athlete role” [6]. Differences in athletic identity and collegiate divisional status (i.e. Division I, II, or III) is mixed (7-8). High athletic identity is positively associated with levels of self-confidence and social interactions [9] and an increase in overall sport performance [10]. Brewer et al. (1993) found that athletes with a stronger athletic identity also place a greater importance on athletics [6]. However, athletes who identify too closely with their athletic role can become more susceptible to experiencing deficiencies in both emotional and physical health, depression, and feelings of isolation with sport transition [6]. Grove, Lavallee, and Gordon (1997) reported that athletes with higher athletic identity also demonstrated a higher degree of psychological adjustment needed to cope with transitioning out of their sport [11]. This transition can be made harder and coping can be more difficult if the cause for change is sudden, such as an injury [12]. Although many different models of coping and adjusting to transition have been established, the current study is based in the competitive sport model [13]. Within this model are two styles of coping, problem- and emotion-focused coping, also known as behavioral- and mental-coping, respectively. Problem-focused coping is centered on changing the problem that is triggering stress in an individual. Emotion-focused coping is based more on controlling the emotions that an individual has when reacting to a situation that causes stress [13]. This model contains different phases of the coping process in response to various causes of stress experienced after a stressful event. This model integrates both behavioral and mental components of coping, and classifies more strategies for coping, therefore making it easier to determine if and how an individual is coping with a stressful event [14]. Coping processes have been found to be one of the most influential factors during an athlete’s transition out of a sport [3]. Folkman and Lazarus (1985) show that both behavioral- and mental-coping skills are used by individuals who experience stressful situations, supporting the notion that coping is a dynamic process which involves using one or more strategies to cope efficiently [15]. Athletes can experience stress while transitioning out of sport, and they can benefit from using both behavioral and mental coping strategies including acceptance, active coping, behavioral disengagement, denial, and humor, mental disengagement, planning, and seeking social support [11]. While research has been conducted to examine coping strategies in athletes who have experienced injury and gone through the rehabilitation process, little research has examined how an athlete handles a career ending injury and the coping strategies he or she uses in order to come to terms with the transition. Further research is needed to examine the coping strategies used by collegiate athletes. The first purpose of this study was to qualitatively examine the coping strategies of NCAA athletes who have sustained a career ending injury. The second purpose was to qualitatively compare and contrast the coping strategies of NCAA Division I and NCAA Division III athletes who have sustained a career ending injury.

2. Main Body

2.1. Participants

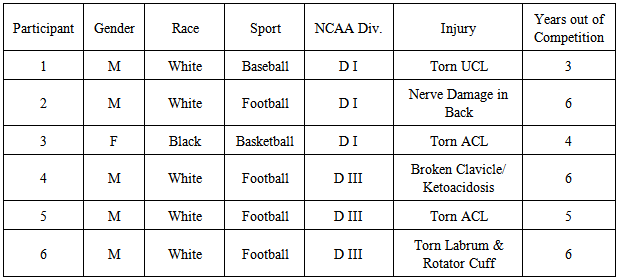

- Six collegiate athletes (three from NCAA Division I colleges and three from NCAA Division III colleges) were interviewed for this study. This purposeful sample was selected based on the snowballing technique, as well as the ability of the participants to describe their experience. These participants were selected based on the amount of information that could be used from the interviews. Participants had experienced a career ending injury while competing at the collegiate level, and they had been out of competition for at least one year. A description of the participants, their sport, and injury is listed below (Table 1).

|

2.2. Instrumentation

- 1. Demographic QuestionnaireParticipants completed a demographics questionnaire in order to collect information regarding gender, race, NCAA College Division (I or III), sport played, nature of injury, and number of years they had been out of competition.2. Interview ProtocolParticipants engaged in an interview session to understand their experience with career ending injury. Due to geographical constraints, participants were interviewed in person or via Skype. Interviews were recorded using a voice recorder application on the researcher’s tablet entitled “Easy Voice Recorder” developed by DIGIPOM, version 1.6. This voice recorder was used to record the interviews and to replay and transcribe the interviews. The semi structured interview guide was used for interviewing participants. For example, one question was as follows: Tell me about the injury you experienced that resulted with you having to stop competing. Probing questions were asked when necessary in order to obtain more information and clarify the participants’ answers. The open-ended questions for this allowed the participant to respond in his or her own words without any leading questions, which can guide the interviewee to say something that they think may be expected by the researcher. Interviews lasted between 20- 30 minutes.

2.3. Pilot Study

- Prior to the researcher conducting a pilot study, a bracketing interview was conducted in order to make the researcher mindful and aware of any biases that they had regarding athletic injuries [16]. A pilot study was then conducted in order to help the researcher enhance interview skills and to ensure that the questions being asked were comprehensible and appropriate. The researcher interviewed an athlete in order to make sure that the questions were clearly understood, and any necessary changes were made to the questions and the interview process in efforts to improve the study. The pilot study interview was recorded and transcribed in the same way that the interviews in the main study were performed.

2.4. Procedures

- The researcher and members of the committee for this study obtained names and contact information of athletes that met the criteria mentioned above. The athletes were contacted by the lead researcher and the study was explained to the athletes. Once the athletes agreed to participate, meeting times to conduct the interviews were mutually agreed upon. The participants were made aware that the interviews would be recorded; however their names could not be traced back to their interviews. Participants were also made aware that the researcher and her team would be the only ones that would be reviewing the data. Participants had the opportunity to review their transcript and validate their responses. The informed consent explained that participants could choose to end their interview at any time.

2.5. Data Analysis

- All of the interviews were recorded and then transcribed into an interview script. Transcripts were prepared by the researcher. The researcher was the only individual that had access to the audiotapes until they were erased. In order to ensure confidentiality, names of participants were changed to numbers. Data analysis was conducted according to a four-step phenomenological process [16]. The steps in this process include approaching the interviews, focusing the data, summarizing the interviews, and releasing the meanings. Once the interviews were collected, the researcher approached the interviews by transcribing the interviews verbatim and obtaining a grasp of the content. The researcher then focused the data by pulling out information that was significant. In this step, the researcher also eliminated any parts of the interview that were irrelevant. Next, the researcher summarized the interviews and gathered all related statements together. After this step, the researcher then released the meanings, identified themes within the interviews, and matched segments of the interviews with the determined themes. In order to establish credibility in the study, triangulation was achieved in the form of interviewer transcription, member checks, and peer debriefing.

2.6. Results

- Upon reviewing the interview transcripts, the following themes were identified: 1) emotional response to the injury- reactions associated with the awareness of no longer being able to compete, 2) redefining identity- the feelings of having to redefine who you are and how you are perceived, 3) adopting a coping strategy- finding a certain resource that helped the individual cope with the transition, and 4) unprepared to cope with the injury- feelings regarding the lack of preparedness to know how to cope with a situation as grave as a career ending injury. Two of the themes contained subthemes. The subthemes for the emotional response to injury theme contained a) initial reaction of shock, b) negative emotions, and c) acceptance. The theme adopting a coping strategy, the subthemes were a) utilizing a support system, and b) focusing attention on something else.Emotional Response to the InjuryEach participant reported experiencing some emotional response to their injury. The responses were broken down into the subthemes of initial reactions of shock, negative emotions, and acceptance. There were some divisional differences in the emotional responses to injury. Only NCAA Division I athletes discussed experiencing an initial reaction of shock. They all reported feeling uncertain about what was happening and what the next steps would be. Participant 1 recalled his feelings right after the injury happened during competition:It was like the strangest feeling ever. I don’t really know how to explain it. I was like I knew something was completely wrong with it, so right then and there, on the field, I had to make the decision to take myself out of the game… things that popped into my head just like, ‘Oh my God. What just happened? What am I going to do?’ so a lot of things flash through your mind when those kind of serious injuries happen.Additionally, along with one NCAA Division III athlete, all three NCAA Division I athletes also discussed experiencing negative emotions in response to their injuries. These negative emotions included devastation, disappointment, frustration, and depression. Participant 6 stated his feelings of depression:At first it was real depressing. At the time, I was pretty depressed. I realized I couldn't play again. I even tried going back my senior year. My shoulder just couldn't handle it anymore. At first it was, obviously, a depressed feeling. Every time fall rolls around, I have that slight depressed feeling because football is here.In contrast, only one NCAA Division I athlete expressed a feeling of acceptance, while all three of the NCAA Division III athletes expressed a feeling of acceptance in regards to their injury. Most of them reported that they experienced the injury, but were able to move on relatively soon afterwards, in some cases, due to that injury experienced. Participant 4 explained how staying connected to the team in some way helped him come to terms with not being able to continue playing:I was still a part of it so I got to translate my playing skills to the kids that I was helping coach while I was there. I think that helped me get over the fact that I wasn't playing anymore. My coach told me he wanted me to stay on and coach and that was something that I wanted to do. That was kind of my aspirations after college. The decision to stop playing led to this coaching position.Redefining IdentityIn the interviews, every participant reported experiencing a change in identity as a result of their injury. Most participants explained that they felt as though they had lost part of their identity due to no longer competing and being on their team. Many of the participants expressed the need to redefine their once strong identity. Participant 2 explained his struggle with losing his identity as an athlete:I think one of the problems with that, especially from a psychological standpoint is that we tend to put our identity into what we do, as I did--I mean was 19 at the time. I thought, ‘Well, football's all I have.’ So, you've got all this publicity from outside, and you've got all these people that want to be a part of this, and as soon as it's over, you find out relatively quickly that you're really not that big of a deal as you thought you were.Participant 5 mentioned being unsure of how to accept his modified identity:Sports were pretty much my entire life and everything else took a back seat. I was known as an athlete. When I realized I wasn't able to play football anymore, I really didn't know what I was supposed to do next. Every year it was play the football season, start basketball season, start baseball season, then train for the upcoming football season. All of a sudden I had more time on my hands and didn't know what to do with it.The data shows that all of the participants experienced a change in identity on their respective teams. Most of the participants had a difficult time adjusting to their new identities, while one participant welcomed the opportunity to change how people perceived him.Adopting a Coping StrategyWhen asked how participants coped with not being able to compete, every participant reported that they relied on various coping strategies. Two subthemes were found to be prominent in this theme: focusing on something else and adopting a support system. Every participant reported that they tried to divert their attention to a different task, whether it was academics, planning their future, exercising, or a combination of these. Participant 1 explained how he focused more of his time on academics and his future:I always remind myself to stay focused on kind of the positive things that I was doing right. I took pride in my school work always, so I knew I had a good GPA, but I stayed focused on my grades. I just tried to stay disciplined and maintained everything that I would do otherwise if I was still playing baseball, really, so I tried to do that, and I guess trying to figure out then what my career goals would be, thinking of other things outside of sports, what I would want to do as far as a job.Participant 4 discussed how staying connected with his team helped him cope:I think it was nice because I was still part of the football program, I was just on the coaching side now. It wasn't like I just stopped playing and then all of a sudden football left, like left my life. I was still a part of it so I got to translate my playing skills to the kids that I was helping coach while I was there, which helped me focus on finding a job as a coach. I think that helped me get over the fact that I wasn't playing anymore.Four out of six participants mentioned the presence of a support system helped them cope with their transition out of sport. These support systems included family, friends, coaches, and athletic trainers. Participant 3 stated the importance and the effect her teammates had on her coping abilities:I guess my teammates ... They was really there for me as far as, cause like I said, a bunch of them had been through a surgery or a time period where they had to sit out. They put me in charge of stuff. When they was free play, I was the ref and I select the teams. I really am so thankful for my teammates. They are awesome. They was awesome during that time and they was very encouraging.All of the participants reported that focusing on a different area of their lives helped them to cope with their transition out of sport. The majority of participants also reported that a strong support system helped make the transition easier. Feelings of Unpreparedness to Cope with Injury and TransitionFour out of the six participants freely expressed that they did not feel prepared to cope with their transition out of sport. The results were evenly split, with two participants from each NCAA Division reporting feelings of unpreparedness. Overall, participants expressed a concern of not being ready for a sudden transition out of sport. Participant 1 felt as though he was not prepared for this transition:I wasn’t really prepared to effectively cope with it. I didn’t know how to cope. I think I could have done a much better job of dealing with it. I wish I would have coped. I say wish, but I think I could have probably coped a little bit better than I did.Participant 6 discussed the abruptness of a career-ending injury, which affected how prepared he felt for the transition out of sport:I was not prepared to deal with that. Nobody can be. Especially when it's so sudden like that. It takes a while to sink in. That next year, they all entered football camp a couple weeks early. When I got to school, they're all still hanging out and had all their inside little jokes and stuff like that. I think that's when it hurt more, and I wasn’t expecting it. It really hit me that I wasn't really going to play.This theme consists of the concerns presented by the participants regarding not feeling prepared for the transition out of sport. Participants attributed not being prepared for this transition to the sudden onset of injury, not knowing how to cope, and not having the issue addressed by the coaching staff.

2.7. Discussion

- The current study examined the coping styles and strategies of NCAA athletes who have sustained a career ending injury, and also compared and contrasted the coping styles and strategies of NCAA Division I and NCAA Division III athletes who have sustained a career ending injury. This section will compare and contrast themes in regard to current research, and recommendations for future research will also be discussed. Emotional Response to InjuryThe theme of emotional response to injury was supported by all of the participants in the study. The second stage of the coping process in competitive sport model [17] is called cognitive appraisal. This stage is where the individual interprets the stimulus as positive or negative. It is important that individuals appraise the event that they encounter in order to effectively cope and reduce any stress that is being experienced. All of the NCAA Division I participants appraised the event as a threat and therefore experienced initial feelings of shock. All of the participants reported experiencing negative emotions including disappointment, worry, depression, and frustration. When viewing an event like an injury as a threat, these feelings are common [14]. The last subtheme, feelings of acceptance, was experienced by all of the NCAA Division III athletes, and only one NCAA Division I athlete. The NCAA Division I athletes saw the event as more threatening, while the NCAA Division III athletes expressed readiness to accept the situation. Lazarus (1993) argued that only events that are appraised as stressful justify the use of coping strategies [18]. However, these findings suggest that even if an individual appraises the event as stressful, but also appraises the event as challenging, or accepts the situation, the individual still utilizes some form of coping strategy.Redefining IdentityThe participants in the study felt as though their identity had been altered due to their injury and reported the need to redefine themselves. The fact that all participants, regardless of NCAA Division, experienced a change in identity is supported by previous research [8]. Every participant reported losing a piece of their identity, and having to rebuild and change their image. Additional research on the topic of athletic identity in NCAA Division I and NCAA Division III athletes is needed to determine whether athletic status influences how transition out of sport through injury is handled. Adopting a Coping StrategyAll six participants adopted coping strategies to help them transition out of their sport as defined by Anshel et al. (1997) [17]. Most participants focused fully on something else, including academics and developing their future, while some participants sought out a support system, including familial and/or social. Anshel (2001) noted that social and familial support is essential in dealing with stress in sport [14]. Focusing attention on another activity and seeking out a support system are both behavioral based coping strategies. Support systems can be classified as approach behavioral coping or avoidance behavioral coping, while focusing fully on another activity or task is classified as avoidance behavioral coping [14]. One participant did mention exercising as a way of coping, which is also classified as an avoidance behavior coping strategy. This finding does not support the conclusions of Gardner and Moore (2006) who suggested both behavior- and mental-coping strategies are used by athletes who have suffered injuries [3]. Although qualitative in nature and taking into consideration saturation, the sample size of the current study was quite small (n = 6) when compared to the previous study [3]. This may be reason as to the dissimilar results. Further research can be done to ascertain if mental-coping strategies are used as commonly as behavioral-coping strategies to help explain the differences in the two coping strategies, the preferred coping strategy by injured athletes, and information on whether it is beneficial to suggest and implement more mental-coping strategies to athletes. Feelings of Unpreparedness to Cope with Injury and TransitionFour out of six participants admitted that they did not feel prepared to handle their transition out of sport. This finding emphasizes the importance of education on the matter of transitions and coping. Transitions are important during any stage of life [12] and the more information that can be disseminated to athletes while they are still in school can better prepare them for transitions they will encounter during their competitive sport careers as well as throughout the rest of their lives.

3. Conclusions

- The current study investigated the coping styles and strategies utilized by NCAA Division I and NCAA Division III athletes who have endured a career injury. Emerging themes included a) emotional response to the injury (initial feelings of shock, negative emotions, and feelings of acceptance), b) redefining identity, c)adopting a coping strategy (relying on a support system, and focusing attention on other things), and d) feelings of unpreparedness to cope with injury and transition. When reviewing previous research on injury and coping, both similarities and differences were found when comparing the current research [3, 14, 17, 18]. This study did present some limitations. There were only three sports represented in this sample, and these sports are three of the most popular in the United States where data was collected. There were also five males in the study and only one female who participated. A more balanced sample with a variety of sports and an equal gender distribution may have yielded different results. One main area of interest based on the results of this study is the possible creation and implementation of programs and interventions that will help collegiate athletes better prepare for the end of their sport career and have a smoother transition out of sport. At some point, the end of a competitive sport career is inevitable, regardless if it is presented as an anticipated or an unanticipated transition out of sport. Introducing athletes to the idea of preparing them for that moment could benefit athletes by reducing the negative emotional responses that may be experienced when transitioning out of sport. An emphasis can be placed on mental-coping strategies, such as positive self-talk, to assist athletes in keeping a clear and focused mind while processing their emotions and effects of their transition. The results from the present study can assist sport psychology consultants, coaches and athletes to better understand the need to cope effectively with sport injury. An athlete could be forced to transition out of sport at any moment, and information readily available on how to understand this stressful experience can help the athlete cope with emotions experience. This information can also help the athlete accept his retirement out of sport and possibly eliminate negative emotions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML