-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2015; 5(1): 8-15

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20150501.02

The Relationship between Pre-Competition State Anxiety Components and Mood State Sub-Scales Scores and the Result of among College Athletes through Temporal Patterning

Bita Mehdipoor Keikha 1, Sarina MD. Yusof 1, Morteza Jourkesh 2

1Faculty of Sport Science and Recreation, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, Malaysia

2Department of Physical Education and Sports Science, Shabestar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran

Correspondence to: Morteza Jourkesh , Department of Physical Education and Sports Science, Shabestar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

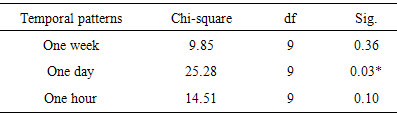

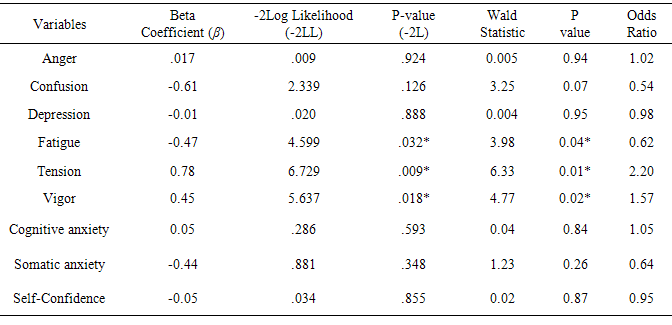

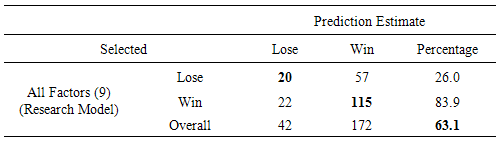

Pre-competition psychological states have been claimed to be one of the factors in predicting sport performance in a varied range of sports. The aim of current study is to measure pre-competition mood states and state anxiety components to predict the result of competition. The number of 219 participants were selected for this study, range from 18 to 26 years old (M=1.74, SD = 0.60 yr.; male = 99, female = 120); who represented the UiTM team participated in the study. The participants completed the Profile of Mood States- Adolescent (POMS-A) and the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2) at three difference temporal patterns including one week, one day and one hour prior to competition. Logistic regression was conducted to assess whether the nine variables, anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension, vigor, cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety and self-confidence, significantly predicted whether the result of the competition is win or lose. The Wald statistics and change in -2 log-likelihood were used to examining the significance of the regression coefficients of the hypothesized predictors. The result of binary logistic regression showed that there were not significant differences in one week and one day hour before competition. However, results revealed that the model was significantly meaningful for three sub-scales of mood state (fatigue, tension and vigor) out of nine measured independent variables only at one day before competition. Remarkably, it means that the model could correctly predict 63.1% of the winners and 26% of the losers. This shows that the regression model for only one day before competition was excelled at predicting the winner and not the losers.

Keywords: State Anxiety, Mood States, Pre-Competition, Result of Competition, Temporal Patterns

Cite this paper: Bita Mehdipoor Keikha , Sarina MD. Yusof , Morteza Jourkesh , The Relationship between Pre-Competition State Anxiety Components and Mood State Sub-Scales Scores and the Result of among College Athletes through Temporal Patterning, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 8-15. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20150501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Pre-competition mood states and state anxiety have been known as two main psychological factors which may be influential on the performance of athletes and their outcomes. Numerous researchers have discussed the effect of environmental and psychological situations on the athletes’ moods and anxiety through scientific and experimental theories (Andrew, Peter, Matthew, Barney, & Sarah, 2004; Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, & Hofmann, 2006; Neil, Hanton, Mellalieu, & Fletcher, 2011). The concept of an extensive difference between environmental demands and responses creates a type of mood for athletes, which may have a positive or negative effect on the result of the competitions. An athlete is expected to handle his/her moods and anxiety symptoms appropriately prior to and during competitions (Alam, 2006). Many researchers carried out studies about the effect of pre-competition mood states on the athletes’ performance (Wong, Thung & Pieter, 2006) while there are also numerous researches about the relationship between state anxiety and performance (Diaz, Glass, Arnkoff & Tanofsky-Kraff, 2001). Whereas, there is lack of literature on the combination of these influential factors and their association with the result of athletic performance even though, there have been researches about the effect of anxiety and mood states on the performance of athletes (Adegbesan, 2007; Lavallee, Sagar, & Spray, 2009). Researchers have commonly applied temporal patterns for evaluating the mood states and anxiety of athletes prior, during or after the competitions. However, in the present study, the researcher applied temporal patterns in three different times prior to competition. Some researchers believe that the closer the evaluation of psychological signs in athletes prior to competitions, the comprehension and precise prediction of performance (Robazza, Gallina, D'Amico, Izzicupo, Bascelli, Di Fonso & Di Baldassarre, 2012). Mood states are regarded as an unstable emotional status in response to an environmental stimulus (Gendolla and Krusken, 2001). They added that moods are able to influence the exertion of efforts. Therefore, any challenge would appear more difficult in negative moods, such as anger, confusion, depression, tension, and fatigue, as opposed to positive moods, such as vigor. Alternatively, when athletes are in a positive mood during the performance, the amount of attempts will be raised before and during competition (Andrew et al., 2004; Neil et al., 2011). Additionally, Terry, Dinsdale, Karageorghis, and Lane (2006) stated that moods are an influential predictor of performance that acts as a transitory constructor when some situations are met. In this regards, Gendolla and Krusken (2001), expressed, despite the fact that internal factors are influential on moods, other factors, such as our prediction of what will happen in the competition, can also be just as important. Sport psychologists have always sought for a standard level of mood states for athletes. Hence, Morgan (1980) proposed an ideal mood state, which is reflected as the iceberg profile. The Iceberg profile theorizes that elite athletes’ characters are shaped by a low level of a person’s negative affective states including anger, depression, tension, fatigue and confusion; and a high level of positive factor namely vigor. This well-known level of psychometric characterized by scores on the area of the Profile of Mood States, is supposed to predict performance of elite athletes (Rowley, Landers, Kyllo, & Etnier, 2007; Covassin & Pero, 2004).State anxiety is one of the variables that are classified into cognitive and somatic anxiety (Kais & Raudsepp, 2005). Cognitive anxiety is regarded as the mental component of anxiety, whilst somatic anxiety is known as the physiological component (Martens, Vealey, & Burton, 1990). They added that cognitive anxiety is characterized based on negative self-talk, worry and unpleasant visual imagery. However, somatic anxiety is diversified through physical reactions such as increase in heartbeat rate, breath shortness, clamminess of hands, anxious stomach, and the increase in muscle tension (Martens et al., 1990). Furthermore, somatic anxiety fluctuates in intensity over time, while cognitive anxiety is more persistent over time based on Patel, Omar, & Terry, (2010) and Ryska, (2012); since cognitive anxiety is more dependent on the sports performance rather than somatic counterpart (Oudejans & Pijpers, 2009). Multi-dimensional anxiety theory advanced through (Martens et al., 1990) focused mainly on pre-competitive sport anxiety. The theory claimed that, there is a decrease in somatic anxiety once performance begins however, cognitive anxiety remains if athletes’ self-confidence is low (Heilman, 2011). This theory characterizes a series of dual-dimensional connections between self-confidence, somatic anxiety, cognitive anxiety, and final performance. Temporal patterning is defined as any change in the perceived symptoms of mood states or state anxiety prior to a competitive event that may have a significant impact on performance (Cerin & Barnett, 2011). In other words, temporal patterns are distinguished by measuring a sportsman’s rate of mood states or state of anxiety three to five times before a competition. It is necessary to understand the temporal patterning in the athletes’ performance before the competition for timing and to control or support against all negative symptoms (Cerin & Barnett, 2011). The results of temporal patterning show that anxiety in pre-competitive state can be regarded as equivocal. Therefore, researchers suggest a basic alteration in the empirical methods of prediction of anxiety in pre-competitive state as the current perception of anxiety, while other complicated emotions are indefinite. However, it is necessary to understand the temporal patterning in the athletes’ pre-competition time conditions and also to control or support all negative symptoms being experienced. Temporal patterns might be capable of detecting the preliminary anxiety and mood states symptoms and subsequently expectations of performance by measuring athletes’ psychological factors more than 24 hours before a competition. Other possible factors affecting anxiety levels and expectation of athletes’ performance might be categorized as motivation, the importance of event, and athlete’s competitive experiences (Welle, 2005). The division of participants into the groups of winner and loser has been performed through numerous researchers (Esfahani, Soflu & Assadi, 2011; Wong et al., 2006). Even though they focused on only one types of sport, the present study examined the variables within many types of sports. Wong et al., (2006) found that winner male college taekwondo athletes had lower cognitive and somatic anxiety and higher self-confidence than their losing counterparts. Based on pre-competition mood states and anxiety, Wong and his colleague were able to correctly predict 91% of participants as winners or losers. Esfahani et al., (2011) by regression statistical data expressed that there is a meaningful relationship between pre-competition mood states of athletes and their performance outcome which could be win and lose in basketball players. The purpose of the present study was to examine the role of pre-competition mood states and state anxiety sub-scales’ scores to predict the result of competition. Although, extensive literatures claimed that the relationship between psychological factors and performance are widely individualized and fluctuating meaning fully from athlete to athlete, the present study was conducted to find a relationship between performance outcome and pre-competition mood states and state anxiety as the influential factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- The focused population of this study composed of Malaysian UiTM students who participated in the MASUM competition. MASUM event has been organized to gather students from Malaysian universities. However, the 500 athletes consisting of males and females were from UiTM University. The athletes were selected from the varied types of sports excluding martial arts. The participants were played at handball, basketball, volleyball, softball, badminton, archery, bowling, lawn ball, swimming, squash and tennis. In this regard, the sample size can be a significant feature of empirical studies where the purpose is to make decisions about a sample from a population. Practically, the sample size used in a research is characterized based on the utilization of data collection, and the need to own appropriate statistical power. For populations that are large, Kotrlik & Higgins, (2001) developed an equation to yield a representative sample for large proportions.

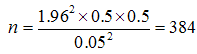

(z) 2 with a ±5 percent margin of error at .95 percent confidence level, the required sample size would be 384.

(z) 2 with a ±5 percent margin of error at .95 percent confidence level, the required sample size would be 384.

Where n is the sample size and N is the Population size (UiTM athletics). The sample size that would now be necessary is shown as:

Where n is the sample size and N is the Population size (UiTM athletics). The sample size that would now be necessary is shown as:

n0 = calculated sample size n = adjusted sample size E = desired margin of errorpq = variance of hypothesized proportionZ = z score of confidence level 95%219 participants was chosen for this study were male and female athletes range from 18 to 26 years (M=1.74, SD = 0.606 yr.; male = 99, female = 120) who represented the UiTM team participated in the present study. The content of the questionnaires (POMS-A and CSAI-2) and the administered times of distributing questionnaires (one week, one day, and one hour before competition) were also explained to the participants.

n0 = calculated sample size n = adjusted sample size E = desired margin of errorpq = variance of hypothesized proportionZ = z score of confidence level 95%219 participants was chosen for this study were male and female athletes range from 18 to 26 years (M=1.74, SD = 0.606 yr.; male = 99, female = 120) who represented the UiTM team participated in the present study. The content of the questionnaires (POMS-A and CSAI-2) and the administered times of distributing questionnaires (one week, one day, and one hour before competition) were also explained to the participants. 2.2. Instrumentations

- Participants were required to fill up demographic information which comprised of age, gender, type of sport, and their involvement in UiTM teams. The questionnaires were administered to measure mood states and state anxiety. These questionnaires were distributed among all participants three times prior to the competition (one week before, one day before and one hour before). Profile of Mood States-Adolescent (POMS-A)In this study, Pre-Competition Mood States was measured by Profile of Mood States-Adolescent (POMS-A) which comprises of 24 items as developed by (Terry, 1999). The questionnaire is derived from an earlier version developed by McNair, (1971). POMS-A questionnaire which also known as Brunel Mood Scale BRUMS consists of 24 items, which assessed six sub-scales: anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension and vigor. Participants were asked to rate the answers based on a 5-point likert scale (0 = not at all, 1= a little, 2= moderately, 3= quite a bit, 4= extremely). Each participant was inquired to rate his/her mood at three temporal patterns which were one week, one day and one hour before competition. Alpha coefficients for the present study were anger=0.72, confusion= 0.83, depression= 0.78, fatigue= 0.70, tension=0.83, and vigor=0.73.Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2)Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2) was used to measure pre-competition cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and self-confidence (Martens et al., 1990). Although, the questionnaire was revised and named as CSAI-2R by Cox and his colligue in 2003, later in 2005 Jones, Lane, Bray, Uphill & Catlin claimed that the construct validity of new version is questionable. Therefore, the researcher used the old version to measure the scores of state anxiety in participants. The CSAI-2 is a self-reported inventory that has been demonstrated to be a reliable (0.70 to 0.90) measurement instrument of cognitive, somatic state anxiety and state self-confidence in competitive situations (Martens et al., 1990). The questionnaire assessed cognitive and somatic anxiety and self-confidence in athletes through twenty-seven items. Each component of state anxiety is measured by nine separated items. The participants were asked to rate the questionnaire by 4-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all; 2 = somewhat; 3 = moderatelyso; 4 = Very much).Alpha coefficients for the present study were cognitive anxiety=0.77, somatic anxiety=0.82, and self-confidence=0.75.

2.3. Procedure

- The project received ethical approval from the UiTM ethical committee. In addition, approvals from various sports coaches were also sought. Upon approval from the head coaches, a meeting with all participants was arranged. During the meeting, the purpose and general overview of the study were explained to the athletes. The content of the questionnaires (POMS-A and CSAI-2) and the administered times of distributing questionnaires (one week, one day, and one hour before competition) were also explained to the participants. All participants were dichotomized into two groups of winners and losers based on their outcome from their first competition on the same day which participants filled up the questionnaires. The data was inputted as the codes in the binary logistic regression analysis to find out the results.

2.4. Data Analysis

- Descriptive statistics were indicated in the demography of the participants. Data is reported as mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) and Frequency tables. Prior to data analysis, normality of all variables was evaluated using skewness and kurtosis. The effects of all variables on the result of competitions (wins and lose) binary logistic regression was applied. All statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS version 19). Confidence level was set at p<0.05. There are several assumptions, which must be considered in binary logistic regression tests. First of all, the Logistic regression does not accept a linear relationship between the independent and dependent variables. While, the dependent variable must be in 2 categories, the independent variables do not need to be interval, nor normally distributed, nor linearly related, nor of equal variance within each group. Final assumption for logistic regression is that the categories must be mutually exclusive and comprehensive as a case can only be in one category and every case must be a member of one of the categories.

3. Results

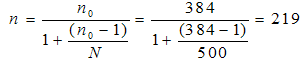

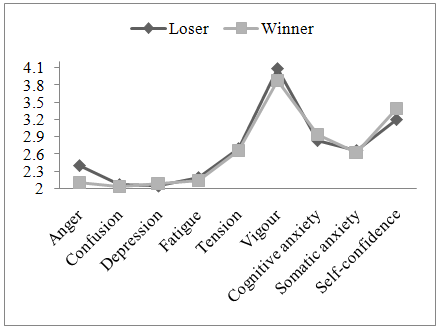

- The sub-scales of mood states and state anxiety from three temporal patterns were converted into standard T-scores to demonstrate differing mood performance relationships among different participants divided into groups of winner and loser. The mean of sub-scales in one week prior to competition as the first temporal pattern (Figure 1) reported almost similar mean between winners and losers. The same level of vigor with other negative sub-scales such as fatigue is inconsistent to Morgan’s (1980) iceberg profile model. However, the multi-dimensional anxiety is supported.

| Figure 1. Comparison of winner and loser mean of mood states and state anxiety at one week prior to competition |

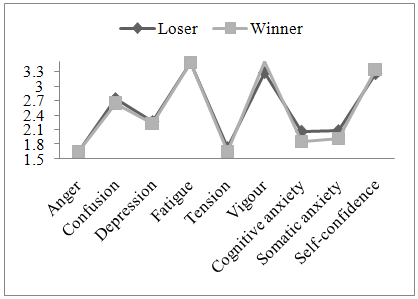

| Figure 2. Comparison of winner and loser mean of mood states and state anxiety at one day prior to competition |

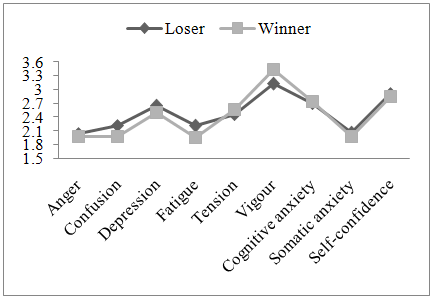

| Figure 3. Comparison of winner and loser mean of mood states and state anxiety at one hour prior to competition |

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Results of the current study showed that, from the perspective of binary logistic regression, pre-competition anxiety and mood responses were predictive of performance outcome at one day prior to competition based on the three temporal patterns of the study. Moreover, the factors of tension and vigor had a positive effect on the predicting of the outcome while the fatigue had a negative effect. It means that through increasing the factors of tension and vigor within one day prior a competition in athletes, the possibility of winning could be increased. The positive effect of tension shows a kind of nobility in the mood states studies. The previous researches indicated pre-competition tension response as a negative mood in athletes (Terry et al., 1999; Ampongan & Pieter, 2005). While, in the result of current study the tension displayed as a positive influential factor in predicting the outcome of competitions in college athletes. The literatures including the famous theory of Morgan (1980) emphasized that except vigor which is known as a positive emotion, the other five main factors are considered as negative psychological emotions in athletes. The current study was inconsistent with Ampongan & Pieter, (2005) who stated that feeling of tension prior to competition is an issue to athletes either professional or amateur and consequently will influence negatively on their performance. Another study carried out by Ampongan & Pieter, (2005) revealed a significant difference in tension were found among professional sports athletes even though this negative mood state did not show any relation to other negative mood states such as anger, depression and confusion. Vigor as another positive factor played a significant role in predicting an athlete’s performance outcome. The findings in the current study are in agreement to other studies (Lim et al. 2011; Ampongan & Pieter, 2005). The findings supported theories which proposed that, mood states affect performance by serving as an informative function, whereby the signal of moods can be helpful to identify the possible issues; mainly in the case of important demands where the outcome of events is uncertain (Beedie et al., 2000; Gendolla & Krusken, 2002). Nevertheless, in terms of fatigue as the only predicted negative significant item, the less fatigue can be concluded to high chance of winning in an athletic competition only in one day before competition start. Since, the Beta Coefficient of fatigue shows a negative point, the less fatigue and be concluded to a more chance of win in athletes. The finding is consistent with a previous study performed by Budgett, (2000) which indicated that the high level of fatigue work as a debilitative factor in athletes and affects the competition outcomes. It must be emphasized that all nine variables even including tension, vigor and fatigue were not statistically significant in one week and one hour prior to competition. It reveals that the sub-scales of mood states and state anxiety did not have and influence in the outcome (win or lose) of the selected population of this study which were the college athletes of UiTM university. Results of the current study showed that, from a binary logistic regression perspective, pre-competition mood responses and anxiety were predictive of performance outcome among college athletes in one day before competition. Predictive effectiveness in the present study which is 63.1% was higher than investigations carried out by Terry & Munro (2008), which yielded 60% correct classifications of performance outcomes of local tennis players. This is possibly explained by the selecting wide range of sports for the present study while they chose only tennis. It is given the proposal that psychological factors show a greater influence on performance at higher competition levels such as university competitions.Furthermore, the results were consistent with Terry & Munro (2008) who claimed that the performances of measured athletes are closely related with pre-competition mindset whereas for some players, performance outcome is unrelated to their anxiety and mood states. These individual differences can serve to conceal the predictive effectiveness of mood and anxiety measures during binary logistic regression analyses and researchers must be aware of this probability during future studies. The study had been carried out by Covassin & Pero, (2004), who found that winning tennis players demonstrated Morgan's (1980) iceberg profile as would be expected in individual sports. Furthermore, winning tennis players in the Covassin’s study exhibited higher vigor scores than the losing tennis players. A possible explanation for the winner demonstrating a higher vigor score may be because he/she is able to maintain a positive attitude in the face of difficult situations. Both groups of tennis players (successful and unsuccessful) showed considerably lower scores on fatigue when compared to college-age norms. Consistent with the results presented by Hassmen, Koivula & Hansson (1998), it appears that fatigue did not play a role in the overall match outcome. Losing volleyball players demonstrated higher scores on tension when compared to both college-age norms and winning volleyball players. If these emotions existed prior to the match, athletes may have been affected by these negative emotions, which in turn may have played a role in their decreased performance and subsequent loss. Volleyball players who had a negative mindset prior to the commencement of their match may have created a situation in which they were so focused on the negative that they were unable to capitalize on any positive aspects of their game during their match. The loser volleyball players in this study had the level of scores on negative moods that were significantly higher than the winner volleyball players and college-age norms. The results of this investigation, in general, confirm the findings reported in earlier studies that found successful athletes to exhibit a higher vigor and self-confidence than unsuccessful athletes (Feltz, Short & Sullivan, 2008). Results suggest that athletes who have a higher vigor entering into a competition are more likely to be successful. One possible explanation is that confident athletes believe in their ability to perform well and win. In many ways, it can be likened to creating a self-fulfilling mindset that enhances the player's ability to either profit from positive events and reduce the impact of negative events during the competition. Outcome expectations are centered on the idea that the things we do, whether they are positive or negative, will influence or make a difference on the result of competition.The current finding supports numerous studies that have shown winning athletes to have lower pre-competitive fatigue than losing athletes (Smith, Smoll, Cumming & Grossbard, 2006; Hatzigeorgiadis & Biddle,2008). One possible explanation is that because winning athletes have higher levels of vigor and self-confidence, they manifested fewer negative expectations and concerns about performance than did the losing players. In the study of comparison of mood in basketball players in Iran League 2 and relation with team cohesion and performance that had been done by Esfahani et al. (2011), it was found that there is a meaningful relationship between psychological traits and performance outcome (win and lose) of basketball players.Future studies must evaluate psychological factors must be measured not only in one game as the constancy of response patterns over time can provide a higher validity in results. Additionally, demographic varieties also necessitate further investigations. More information requires to be collected on whether or not gender role, age, socio-cultural, years of experience in the field of performance and skill level among athletic participants are related to specific state anxiety and mood states components.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML