-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2014; 4(6): 223-229

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20140406.04

A Survey of the Practice of Physical Education and Sports for all in Secondary Schools in Bomet County in Kenya

Kipng’etich Kirui Joseph1, Rotich K. Alexander2

1School of Education, Department of Curriculum, Instruction & Educational Media, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya

2School of Education and Social Sciences, Department of Social Sciences, University of Kabianga, Kericho, Kenya

Correspondence to: Kipng’etich Kirui Joseph, School of Education, Department of Curriculum, Instruction & Educational Media, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The low status of physical education in schools has increased sedentary lifestyles of learners. The objective was to assess the extent to which the practice of physical education formed a fundamental right for all learners in secondary schools in Bomet County. The Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS) model of curriculum development and implementation guided the study. This study utilized descriptive survey method of research. The sampling designs used included simple random and convenient sampling whereas questionnaire, interview guide, and observation were the tools of data collection. A total of 281 respondents took part in the study. Data analysis was done using both descriptive and inferential statistics. The study found that students are denied their right to be educated physically in schools in Bomet County and it recommended that the Directorate of Quality Assurance and Standards (DQAS) in Kenya should send adequate officers to this county who will be responsible for monitoring and evaluation of physical education in schools.

Keywords: Curriculum implementation, Fundamental right, Physical education

Cite this paper: Kipng’etich Kirui Joseph, Rotich K. Alexander, A Survey of the Practice of Physical Education and Sports for all in Secondary Schools in Bomet County in Kenya, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 223-229. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20140406.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

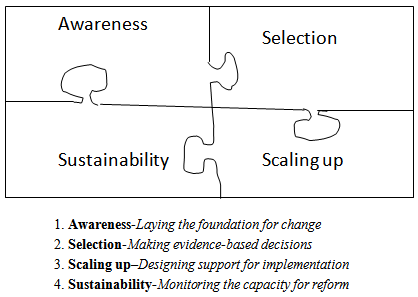

- Insuring physical education curricula is a responsibility of physical educators, with ultimate accountability resting with the profession; and insuring quality physical education experiences for every student calls for advocacy by the profession; and professional physical educators are primary care-givers of students with regard to physical education; and schools are primary venues through which physical education should be delivered.The International Charter of Physical Education and Sport [1], and supported by UNESCO Member States (Preamble Art. 1, 1978; reaffirmed by ICHPER.SD [2] declares access to physical education for all, that is, physical education and sport is a fundamental right for all. And Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNICEF, Art.29, Sec. 1a, b, September 2, 1990 [3], states that education shall be directed to: the development of the child’s personality, talents, and mental and physical abilities to his/her fullest potential; the development of respect of human rights. ICHPER.SD [2] resolved to develop global standards identifying essential knowledge and skills central to school programmes (Seoul Resolution on the Right of School-Age Youth to be Physically Educated, [4]). It also advocates for and enables developing of quality daily physical education programmes in schools worldwide; it further urges other multi-national organizations and non-government groups to advocate for greater prominence of and right of all school-age youth to quality physical education programmes. The World-Wide Survey [5] with the support of ICSSPE and other international and regional agencies affirmed that physical education has been pushed into a defensive position, suffering from decreased time allocation, budgetary constraints, low academic status, and under valuation by authorities. The survey advocated increased, action oriented partnerships of all concerned organizations and agencies; concerted international actions by all concerned to enable compliance with UNESCO’s advocacy statement espousing the principle of physical education as a fundamental human right.The pressure of examination and general apathy from all concerned has dealt a blow to the implementation of the physical education curriculum in secondary schools in Kenya. The issue of concern in this study was that one of the measures of the success of a curriculum is the learning that takes place. The pressure of examinations, many and congested academics programmes, small play- grounds both in rural and urban areas, mushrooming of unregulated ‘academies’, raising of the number of lessons per teacher under Curriculum Based Establishments (CBE) to a minimum of 27 per week by the Teachers Service Commission (TSC), and the low status of physical education has deprived the learners in schools of their right to quality physical education. This has become a recipe for a myriad of problems in schools ranging from poor academic achievement, lack of teamwork, health problems (young people especially those below 30 years now getting (Type 2) diabetic because of sedentary life or lack of exercises) to simmering hostilities leading to strikes in schools. The recent syllabi change by the former KIE in 2003, put Physical Education lessons at one lesson for forms one and two and two lessons for forms three and four (duration of a lesson is 40 minutes). Nevertheless, teachers are not implementing this programme. This has raised the question: are the learners in Bomet County being exposed to the right quality of physical education in secondary schools as their fundamental right?The objective of the study was to assess the extent to which physical education is practised as right for all learners in secondary schools in Bomet County in Kenya. The study measured the hypothesis:HO1 The amount of time given to physical education and the awareness by the teachers that students have a right to physical education are independent of each otherThe hypothesis was tested at alpha (α) level of 0.05.From the research findings, it is expected that the TSC (Teachers Service Commission) and KICD (Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development) would use the findings to re-assess the state and status of Physical Education insecondary schools and come up with appropriate strategy on the policy of Physical Education that firmly secures the future of our youths in terms of physical fitness. This research would also enrich the literature on Physical Education and Sports in Africa and Kenya in particular since there are no previous researches hitherto on this topic.According to the National Children and Youth Fitness Study [6], the number of children not doing physical education is constantly rising across the globe as shown by several studies like World-Wide Survey by Hardman and Marshall [5] and Hardman [7]. Physical education has long been an integral part of the school curriculum. However, many times the instruction declines progressively along the education ladder. The educational philosophy today is to compromise or even eliminate psychomotor domain or physical development in the hope of improving one’s cognition. The school set-up has become so oppressive to the child that the UN International Charter of Physical Education and Sports [1] is never taken into account. Article 1 of this charter has it that the practice of physical education and sport is a fundamental right for all. It is synonymous with Education For All (EFA). In developed countries, computers and video games are considered as the principle reason why young people drop sports and physical education completely. This same phenomenon is catching up with the developing countries. In Kenya, examination and the notion that over- teaching improves results have even made teachers of other subjects to use Physical Education lessons to cover their own syllabi. It is plausible that a decline in all aspects of the educational paradigm will suffer from an unbalanced approach to improving the whole.This study was based on the BSCS (Biological Sciences Curriculum Study) model because it is rooted in the transformation orientation position. BSCS was a national curriculum development project of 1960s. It is an example of the ideological curriculum. Ideological curriculum is the ideal curriculum as construed by scholars and teachers - a curriculum of ideas intended to reflect funded knowledge. It adopts the design given in Fig 1.

| Figure 1. The BSCS Model |

2. Literature Review

- National curriculum implementation is a complex matter [8]. Equally, a generation of unmotivated, overweight, inactive, delinquents and technological couch individuals is in the offing lest Physical Education curriculum is not only in placing but seen to be functioning in secondary schools. After independence, the government saw it important to address the issue of educational relevance. The main aim of most of these changes in the education system is to improve the quality of education at all levels. It is envisaged that it is through the subjects that will be learned that learners will be able to develop their talents to the full. The philosophy of education, which must always be in consonance with national philosophy in order for education and training to contribute positively to national development, has been the guiding principle. As shown in the theoretical framework, in implementation, creating awareness is important. People do not like change by nature because change creates what Piaget called disequilibrium. That is, when somebody’s beliefs are challenged, they lose the balance. When new ideas come, they look for a way to maintain that balance by putting the new ideas into use. In curriculum implementation therefore, people in authority, teachers, and parents have to be made aware of the innovation. If one team is not successfully made aware, then the implementation will be hampered. Awareness then, is laying foundation for change in physical education. It is building the awareness that high quality instructional materials matter in the learning process for students. The implementers ought to be aware that instruction suffices only where awareness of the teaching materials are prioritised. In addition, that use of non- standard sub- standard materials can even be dangerous to the learners. This awareness will then lead to the initiation of the development of leadership capacity through, forming school- and district based leadership teams. In the USA, the AAHPERD has regional based teams like LAHPERD, IAHPERD, CAHPERD etc. this awareness equally establishes the need for change based on using school and County data on student achievement and teacher capacity. The next element in implementation is selection. This is making evidence-based decisions. In physical education, such issues as the nature and quality of existing materials and equipment, and the nature, quantity and quality of new materials and equipment and those responsible for preparation will be addressed. At this stage, there is empirical evidence on mode of piloting and evaluation of instructional materials that serve as a professional development strategy prior to implementation. Teachers should also develop a common ground about the characteristics of high quality, inquiry oriented instructional materials. Quality refers to both the quality of the content as well as physical quality. The teachers of physical education should make most evidence-based decisions because they are the ones with first-hand knowledge of how schools operate, and since they form the single most group of professionals who are going to use these materials. It is here where team effort comes in. Existing ideas and expertise among the teachers should be pooled together in the preparation and production of high quality materials. Care must be taken to ensure that high standards are set by the team of teachers based on their district or regional organisation to avoid acquisition of low quality instructional materials and equipment. This in essence is building consensus during the decision making process, by establishing selection criteria based on research and the needs of teachers and students in the County (Bomet). A survey is done to establish the needs of teachers and students in that district in that particular area. When this is done, resistance to change will reduce.Scaling-up is designing support for implementation. A general apathy is often noted in curriculum implementation because the public is never informed adequately about the projects being planned and implemented. This stage involves designing a transformative professional development programme that supports the implementation of high quality, inquiry-oriented instructional materials. Transformative oriented programme in physical education focuses on personal and social change, which is, teaching skills that promote personal and social transformation in student which are called humanistic and social change orientations. The learner is supposed to be transformed through interaction with the teacher as seen in the work of Rousseau and Froebel [9]. It also incorporates a variety of professional development strategies and evaluation tools. The Ministry of Education Science and Technology should ensure that physical education teachers continuously upgrade their skills to go with times through appropriate courses, seminars, workshops etc. The syllabus (Physical Education) stipulates that assessment be continuous and be an integral part of the teaching and learning process.In this adoption level (scaling–up) building of the local improvement infrastructure that will provide on-going support within the system for effective implementation should be done. Many innovations fail because of lack of support. Teachers need monetary, time, material, human, peer and agents (QUASO, head teacher, Teachers’ Advisory Centre-TAC, Board of Management -BOM) support [10]. There should be a centre within the school where people can come for more support and consultation as they implement the new programme in case a problem arose. Presently TACs are spread across the country. It is vital to know if these centres equally cater for teachers of physical education.Finally, sustainability in implementation deals with the capacity for reform. It does this by improving the capacity of the system to move forward, it provides continuous improvement for teaching, and learning by developing site based leadership. It also monitors and adjusts interventions based on data that documents students learning, teaching practice, formative classroom assessment, professional development support and system infrastructure and capacity. It at the same time, sustains effective professional development using strategies such as examining student work, collaborative lesson study and action research. One observes events as the programme progress and collects information to inform on the success or otherwise. It will help to decide whether to sustain. Finally, this level bases professional development on data of teachers’ attitudes about abilities to use and understanding of new instructional materials. Any professional development that comes during this period is based on attitude, ability to use new materials and assess their understanding of new materials.

2.1. The Critical Stage in Life for Physical Education

- The adolescent or young adult at the secondary school is at the critical stage of his/ her life. This crucial period affects the holistic development of the student as he/she prepares to make the transition and maturation into full adulthood. As such, the lifestyles habits practiced by students during this phase can have significant consequences into their adult lives. In addition, the lifestyle choices cultivated by students during this transitional stage will most likely be adopted into their adult lives. Thus, it is paramount for educators and the general education agents in the country to create an environment where students develop into solid responsible citizens, by providing opportunities for students to make good decisions about their lifestyle choices. It is the patriotic duty for physical educators at secondary schools to educate their students about the importance of engaging in regular physical activity.Student should also be exposed to a variety of physical activities, traditional and non- traditional to encourage them to select physical activities for lifelong participation and enjoyment. Students should also be provided with challenging opportunities to develop strength of character and respectful environments to foster positive socialization skills and respect for all individuals in order to cultivate their holistic development and nurture them into upstanding citizens of the public.Emphatically, physical education at the secondary school plays a vital role in cultivating students to adopt healthy lifestyles and lifelong physical activity involvements to counter health and fitness problems, as well as nurturing students into upright, responsible citizens to combat many of today’s societal woes, such as violence, hatred, discriminations, substance abuse, promiscuity, and others.However, physical education in schools, as Morgan [11], an award-winning lecturer in Health and Physical Education at the University of Newcastle, says is inhibited by low status (not examinable); it receives reduced time in the school curriculum and poor quality programmes.

2.2. The Teaching Gap

- The situation in the country on physical education demands improvement, not just, because improvement is possible but because it is needed. Our students could be learning much more and much more deeply than they are learning now. Teachers in Kenya are increasingly aware of this learning gap and seeking ways to address it. Policy makers carefully study subject-by-subject scores on the most recent Kenya National Examination Council Report for loopholes to improvements. Scores of all top performing schools are printed in the local daily newspapers, and school boards and parents discuss why students in some schools score much lower than the others. Unfortunately, the policymakers though they have designed a very good curriculum for physical education, have ignored the fact that making such elaborate curriculum about physical education without even the most rudimentary information about what is happening in schools is futile.

2.3. Subject and Teacher Status in Kenya and the Rest of the World

- The view that physical education “has generally occupied a low position on the academic totem pole (and) has been held in low esteem” [12] is acknowledged in many countries like Italy, Norway, Netherlands and others and this cannot be more true in Kenya. This survey’s further findings point to teachers of physical education enjoying the same status as other subject teachers. For example, in Georgia and Slovenia they are adjudged to have higher status. Only in Austria is there an indicator of lower status for teachers of physical education in some schools. However, these findings on subject and teachers of physical education status stand in contrast to widely held published literature assertions that physical education suffers low status and esteem. The situation is exemplified in statements on lower importance of school physical education in general, lack of official assessment, loss of time allocation and diversion of resources elsewhere. Data from the above surveys suggests that the actual status of physical education in relation to other school subjects is regarded as lower than that accorded within the legal framework and hence, underscores the literature. In short, legally it has similar status but in reality, it does not.In Central and Eastern Europe, in spite of government directive on physical education as a curriculum requirement, low subject status is evident in several countries. According to one physical education professor [7].Many Bulgarian head teachers are said to be too much occupied with other engagements to be able to pay attention to the PE of the pupils and whilst other teachers understand the necessity of sports (they) think that their subject is more important for their children (p.168).Within some circles in France, the intellectually demanding education curriculum has resulted in physical education being merely a diversion or even a burden to be borne in order to pass examinations.Here, in Kenya, greater value is attached to academic subjects with physical education more generally associated with recreation. Physical Education is a subject, which is considered of far less importance than other academic subjects in the school are. When teachers have problems in finishing the programmes or syllabi of Geography, or Physics for example, they cut on Physical Education lessons.From Worldwide Survey [7], prevailing common perceptions amongst ‘significant others’ (head teachers, other subject teachers and parents) towards physical education were that physical education is a non-academic, non-constructive vocationally non- productive, peripheral subject with an orientation to compensatory recreational rather than educational activity. There is a prestige differentiation between physical education and other subjects. As a ‘practical subject’, it is regarded as subservient in a subject hierarchy that is grounded in an intellectual- practical divide. It is a divide, which gives more credit ‘to what you can do with your mind rather than what you can do with your body’ [13].One indicator of subject status is frequency of cancellation of lessons. In the CDDS survey, some countries (like Denmark, Italy, Slovenia) acknowledged that lessons are cancelled more often than those of other subjects are, though in other schools the frequency to cancel lessons is the same for all subjects. However, other surveys bring another reality. It seems that the low status and esteem of the subject are detrimental to its position, because in many countries, physical education lessons are cancelled more often than so called ‘academic subjects’. Other reason given for cancellation of physical education includes the use of the dedicated physical education lesson space for examinations and concerts. In many countries, Kenya inclusive, the approach of the end of the school term, semester or year is marked by the cancellation of physical education lessons to make way for teaching or revision of other subjects in preparation for(internal and external) examination.

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Research Area

- The study was carried out in Bomet County in Kenya. It lies between latitudes 0° 29’ and 1° 03’ south of the Equator and between longitude 35° 5’and 0° 35’ east. It is in southern part of Rift Valley. Part of the County is covered by multi-national tea companies, and Chepalungu gazetted forest occupies 50.041 Km2.

3.2. Research Design

- The study utilized a descriptive survey method of research. A survey research collects data about variables of subjects as they are found in a social system or society. The central feature of survey is the systematic collection of data in a standardized form from an identifiable population or representative sample. The study sought to describe and or analyze the aspects of physical education as they are in secondary schools in Bomet County.

3.3. Sampling Frame

- Bomet County has 71 secondary schools. The total numbers of students in all the secondary schools were 15413. There were also 504 secondary school teachers in the County distributed in all the six divisions. The County also has 4 QUASOs.

3.4. Sampling Procedures and the Sample

- To get a representative sample and significantly reduce chance error in the study, all the schools in the County were stratified as Boys’, Girls’, and Coeducational (Mixed). The purpose of stratifying was to organize the sampling frame into homogenous subjects from which a sample was drawn, ensure parity in representation of each category, and provide each school with an equal chance of being drawn for the study. To calculate the number of sampled schools per category, the total numbers of schools in each category were multiplied by the ratio of schools sampled to the total number of secondary schools in the County [14].

3.5. Research Tools

- This study was carried out using questionnaires, interview guides and observation. The teachers of Physical Education, and students completed the questionnaires.

3.6. Reliability

- Mugenda and Mugenda [15] say that, the reliability of a measuring instrument refers to the instruments ability to yield consistent results each time it is applied. Test/Re-test method was used to determine the reliability of the Teachers and Students’ questionnaire. After piloting of the tools of research, Pearson Product Correlation Co-efficient (r) was calculated between the first test and the re-test, which took place at interval of two weeks. Two weeks was considered long enough to avoid recall by the respondents on the first test and short enough for maturity of the respondents and achievement of similar conditions as the first test. The calculated rfor the Teachers’ Questionnaire was 0.798 and that for the Students’ Questionnaire was 0.808. The instruments were thus considered reliable because a correlation of 0.5or > is acceptable.

3.7. Data Collection Procedures

- A reconnaissance trip was done in the research area after clearance from the School of Education – Moi University and the MOE giving research permit. The research tools were administered to respective respondents by the researcher. Each respondent was encouraged to respond individually. Enough time was given to all respondents for accuracy purposes. In addition, the researcher carried out observation.

3.8. Data Analysis

- Descriptive and inferential statistics were employed in data analysis. For descriptive statistics: frequency tables, pie charts, bar graphs, percentages, standard deviations, means and histograms were used. T-test at a significant level set at 0.05 was employed for inferential statistics. 0.05 levels is the standard recommended for Social Sciences researches. Data collected were measured at ordinal, nominal, ratio and interval scales. The use of t- test on ordinal and nominal variables are based on the postulations of Cohen and Manion [16] that the use of t- test is about 95% as powerful as Mann-Whitney test, meaning that t-test requires only 5% fewer subjects than Mann-Whitney test to reject the HO when it is false.

4. Data Analysis, Presentation and Interpretation

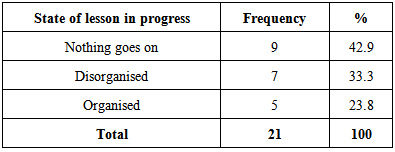

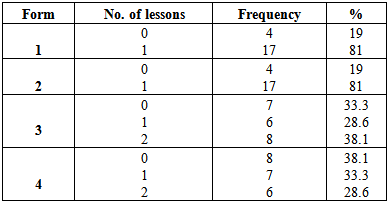

- From the Table 1, it was observed that in 33.3% and 42.9% of the sampled schools, physical education lessons where students were lucky to attend were disorganised and nothing went on completely respectively. Students were just basking in the sun. In addition, in one of the sampled schools, the school ran a 10 lesson per day programme as opposed to 9 lessons as recommended by the ministry. Further, the school had not included any physical education lessons on the timetable yet it has two teachers trained in Physical Education. Equally, as seen in Table 2, the statuses of Physical Education vary from school to school as seen from the timetabling.

|

|

4.1. Hypothesis Testing

- HO There is no relationship between the attitude of students towards physical education and the use of physical education lessons by other teachers to teach their own subjects. A t-test to indicate if students’ attitude towards physical education and teachers using physical education lessons to teach their own or other subjects other than physical education would be significant was done. A P value of 0.150 was obtained which was more than the 0.05 value and so the null hypothesis was retained. Teachers using physical education lessons to teach their own or other subjects other than physical education during periods designated for physical education were bound to affect the attitude of students. It can then be summarised that this research found that students are denied their right to be educated physically in schools in Bomet County.

4.2. Discussions

- It was found that mostly, students are denied rights to physical education in most of the schools sampled. As much as the teachers saying they are aware that students have a right to be educated physically, teachers of other curriculum subjects used physical education lessons to cover on their own syllabus. It also emerged that school programmes such as concerts and Continuous Assessment Tests utilized physical education periods. The County QASO was emphatic that nobody knows what to look for in physical education during their routine inspection in schools and more so that they were not aware whether physical education falls under the sciences or humanities in the curriculum. School administrators were also apathetic to physical education. They have either given physical education less time or removed it completely from the timetable. Teachers also do not teach physical education as they do in other subjects. Teachers are not exposed to current trends in physical education, as most of them do not attend INSET courses. To improve the teaching of physical education in schools, we must invest much more in sharing knowledge with one another. It was found that the few teachers who trained in physical education were already overworked in other areas of curricula, thus jeopardizing their willingness to take more lessons on physical education. This high workload, congested curricula and general apathy of the TSC advocacy team has pushed physical education to the periphery of the school curriculum. It therefore emerged from the research that physical education has always been a second-class citizen in the curricula. This contravenes The International Charter of Physical Education and Sport [1] which is supported by UNESCO Member States. It is also against the Convention of the Right of the Child [3] Art. 29 of which Kenya is a signatory.

4.3. Conclusions

- A review of the implementation of the physical education curriculum in secondary schools in Bomet County was done. The research found that the students in secondary schools are largely denied a chance to participate fully in physical education. Their fundamental human right as stipulated by the UN Convention was infringed upon.

4.4. Recommendations

- From the research findings, the following recommendation was made: QASOs to be taken to county, district and divisional levels that are responsible for periodic monitoring and evaluation of physical education in schools.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The researchers wish to appreciate the support given by Moi University towards this study. We also thank the secondary schools that were used in this study in Bomet County and the County Government of Bomet. We also appreciate the input of Prof. Too J.K of the School of Education Moi University.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML