-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2014; 4(6): 205-211

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20140406.01

Psychosocial Correlates of Physical Activity Participation among Nigerian University Students

Taofeek O. Awotidebe1, 2, Rufus A. Adedoyin1, Olufemi A. Adegbesan2, Joseph F. Babalola2, Idowu O. Olukoju1, Chidozie E. Mbada1, Esnat Chirwa3, Lukman A. Bisiriyu4

1Department of Medical Rehabilitation, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile - Ife, Nigeria

2Department of Human Kinetics and Health Education, Faculty of Education, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

3School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

4Department of Demography and Social Statistics, Faculty of Social Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile – Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Taofeek O. Awotidebe, Department of Medical Rehabilitation, College of Health Sciences, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile - Ife, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

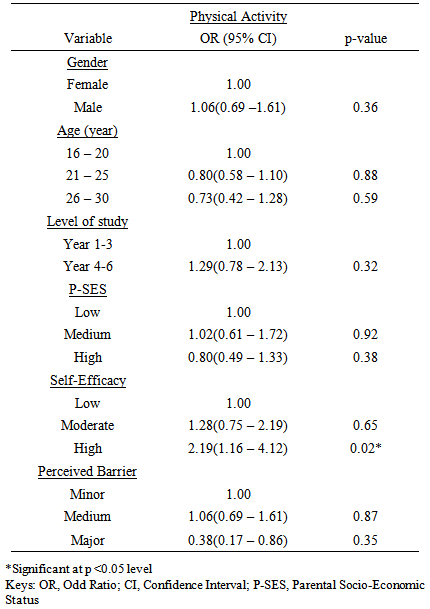

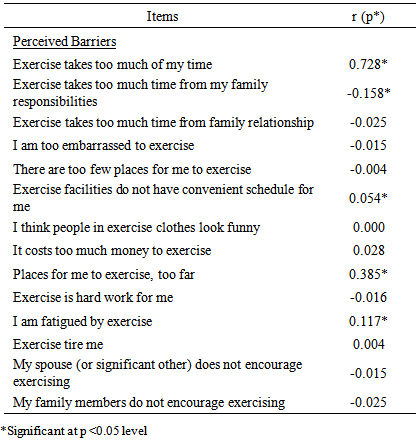

Background: Studies on psychosocial correlates of Physical Activity (PA) in a previously unexplored cultural context of sub-Sahara Africa are sparse. This study assessed psychosocial correlates of PA among Nigerian university students. Methods: This cross-sectional study recruited 1600 students of the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile – Ife, Nigeria. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to assess PA at 7-day recall (MET-min/week) while psychosocial variables of Exercise Self-Efficacy (ESE), Perceived Barriers to PA (PBPA) and parental Socio-economic Status (SES) were assessed using ESE, PBPA and SES questionnaires respectively. However, 1399 completed the study yielding a response rate of 87.4%. Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Alpha level was at p < 0.05. Results: A majority of the respondents, 89.4% reported sufficient PA. High self-efficacy was twice more likely in male (OR = 2.19, C.I. = 1.16 – 4.12) than female counterpart (OR = 0.46, C.I. = 0.29 – 0.72). Significant association was found between high self-efficacy and sufficient PA (OR = 2.19, C.I. = 1.16 – 4.12) (p< 0.05). Perceived barrier items such as time constraints, exercise facilities do not have convenient schedule and exercise causes fatigue were significantly correlated with PA (p< 0.05). Conclusions: A majority of the surveyed Nigerian university students demonstrated sufficient PA over the course of seven days. Perceived self-efficacy was significantly associated with sufficient PA while perceived barrier and parental socio-economic status were not.

Keywords: Physical activity, Psychosocial correlates, Nigerian University students

Cite this paper: Taofeek O. Awotidebe, Rufus A. Adedoyin, Olufemi A. Adegbesan, Joseph F. Babalola, Idowu O. Olukoju, Chidozie E. Mbada, Esnat Chirwa, Lukman A. Bisiriyu, Psychosocial Correlates of Physical Activity Participation among Nigerian University Students, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 205-211. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20140406.01.

Article Outline

1. Background

- Presently, sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) is witnessing rapid epidemiological transition and plagued with high prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, type-2 diabetes and some cancers [1]. Evidence from epidemiological studies have however, shown that participation in Physical Activity (PA) as a form of health behaviour offers a recognizable health benefits in preventing chronic NCDs [2, 3]. Owing to enormous benefits of PA, many health organizations have advocated moderate to high intensity PA [4, 5]. Despite these recommendations, there is substantial evidence that PA rates decline consistently among adults [6]. Data on the prevalence of PA in African varied widely from country to country, for instance, the prevalence of physical inactivity was reported to be 49.1% and 44.7% in Swaziland and South Africa respectively. Countries such as Mozambique and Malawi in southeastern Africa, had the highest reported prevalence of physical activity (around 95%) [7]. (Guthold et al, [7], further reported that two countries in West African sub-region, Mali and Mauritania, having prevalence of about 50%. The reasons for these differences were not identified. However, recent data from northern Nigeria in a study by Oyeyemi et al, [8] reported a prevalence rate of 68% among adults and factors such as social, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics were identified as determinants of PA participation. Physical activity as a form of health behaviour may be influenced by a gamut of factors not limited to demographic, socio-cultural, environmental, socio-economic and psychosocial variables. These factors are not mutually exclusive but inter-related in their influences on health behaviour [9]. The Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) suggests that knowledge of health risks and benefits are prerequisite to change, additional self-influences are necessary for change to occur [10]. Beliefs regarding personal efficacy are among some of these influences which play a central role in health behaviour. According to Adeniyi et al, [11], the SCT provides a framework that simultaneously addresses self-efficacy, perceived barriers, outcome expectancies and self-regulatory behaviours as related to PA participation, however factor such as Socio-Economic Status (SES) has been reported to contribute to lifestyle and health behaviour [12]. SES may affect knowledge of benefit and health-promoting behaviours [13], and it is also thought to be a mediator of psychosocial determinants of PA [14]. Conversely, some studies have reported psychosocial factors as mediators of SES [15, 16].Shibata et al, [17] submitted that a better understanding of the contributing factors that influence PA is critical in designing relevant policies and effective interventions. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of information on factors influencing PA participation across various populations in SSA. Hence, this study assessed psychosocial correlates of PA among young Nigerian university undergraduates.

2. Methods

2.1. Respondents

- One thousand six hundred undergraduates of the Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), Ile –Ife, Nigeria participated in this cross-sectional survey. The Obafemi Awolowo University is a public funded first generation university established more than 50 years ago. It is located in the ancient city of Ile-Ife, the ancestral home of the Yoruba tribe in southwest, Nigeria. The city has a population of about half a million and is centrally located within the Yoruba city-states. Ile-Ife is about two hundred kilometers away from Lagos, which was Nigeria’s coastal capital city for over a century. To the west lies Ibadan, the largest city in sub-Saharan Africa and to the east lies Ondo, gateway to the eastern Yoruba city-states [18]. Obafemi Awolowo University comprises of central campus, the student residential area, the staff quarters and a Teaching and Research Farm. The central campus comprises the academic, administrative units and service centers while the student residential area is made up of 10 undergraduate hostels and a postgraduate hall of residence. The total population of student is about 35,000.Eligibility for inclusion were undergraduate students of the Obafemi Awolowo University, whose ages range between 16 and 30 years and were residing in the halls of residence on campus. Students with self-reported medical or musculoskeletal conditions were excluded from the study. Out of the 1600 copies of questionnaire administered, only 1399 were found valid for analysis yielding a response rate of 87.4%.

2.2. Procedure

- Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile – Ife. Nigeria. Respondents were recruited using purposive sampling methods. The informed consent of all respondents was obtained. The survey was carried out between 16:00 to 20:00 hours when the students could be met in the respective halls. Information on socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender and educational level of study were obtained while the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to assess PA at 7-day recall. Psychosocial information obtained included exercise self-efficacy, perceived barrier to PA and parental SES using Exercise Self Efficacy (ESE), Exercise Benefits and Barrier Scale (EBBS) and Socio-Economic Status (SES) questionnaires respectively. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) The IPAQ short-form was used to assess the PA level and has been reported to have acceptable test-retest reliability and criterion validity [19, 20]. Respondents were asked the number of days they did vigorous PA, moderate PA (not including walking) and walking, as well as the number of hours and minutes per day they did the three kinds of activities in the last 7 days respectively. These activity categories can be treated separately to obtain the activity pattern or may be multiplied by their estimated intensity in METs and summed to gain an overall estimate of PA in a week (www.ipaq.ki.se). One MET represents the energy expended while sitting quietly at rest and is equivalent to 3.5 ml/kg/min of VO2. The MET intensities used to score IPAQ in this study were vigorous (8 METs), moderate (4 METs), and walking (3.3 METs) (www.ipaq.ki.se). Physical activity levels were initially classified as low, moderate, or high intensity, defined by the IPAQ core group (http://www.ipaq.ki.se) as follows: Low—no activity or some activity reported, but not enough to satisfy the requirements of the other activity categories; Moderate—any of the following 3 criteria: (a) 3 or more days of vigorous-intensity activity for at least 20 minutes per day, (b) 5 or more days of moderate intensity activity or waking for at least 30 minutes per day, or (c) 5 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate intensity, or vigorous-intensity activities achieving a minimum of 600 MET-minutes per week; High—either of the following 2 criteria: (a) 3 or more days of vigorous-intensity activity accumulating at least 1500 MET-minutes per week or (b) 7 days of any combination of walking or moderate- or vigorous intensity activities achieving a minimum of 3000 MET-minutes per week. These 3 groups were then categorized as sufficiently PA or insufficient PA. The sufficient PA group included respondents in the moderate- or high intensity categories who met the WHO physical activity recommendation. According to the new WHO global standard, satisfying the recommendations for healthy physical activity was defined as engaging in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week, 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity per week, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity [19]. Parental Socio-economic Status QuestionnaireParental SES was considered a valid assessment of SES among Nigeria undergraduates because study and work plan is sparse owing to high unemployment rate, therefore, their SES will largely be a reflection of their parents’ or guardians’. Based on previous studies in the study’s locality, SES indicators such as education, occupation and income were often combined in the assessment of SES level [21]. The present study used a SES questionnaire by Adedoyin et al [21], where education, occupation and income were the major SES indicators. Furthermore, parent’s possessions of house, cars, and household assets such as television, video, refrigerator and set of upholstery were considered as part of SES indicators. Parent’s position in the community such as community leader or religious leader including pastor, imam or chief were also considered as SES indicator in Nigeria context. The scoring of the items on the questionnaire was based on their importance in Nigerian society. The summative scores of the three socio-economic indicators and respective valued properties and position in the community were added together to yield a maximum obtainable score of 27 points. Actual score was divided by maximum obtainable score and then multiplied by 100. The 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles was used to label transformed-scores into lower, middle and upper quartiles representing “low”, “moderate” and “high” levels of socioeconomic class. The instrument has good test re-test reliability value (0.86).Self-efficacy for Exercise Behavior Scale Exercise Self- Efficacy (ESE) was assessed using the Self-Efficacy for Exercise Behavior Scale [22]. It comprises of 2 subcategories, Self-Efficacy for Resisting Relapse (self-regulatory), which contains 5 items, and Self-Efficacy for Making Time, which contains 6 items. The Self-Efficacy for Resisting Relapse was used in this study and each item elicits questions on perceived self-efficacy. The scale asked respondents to rate how confident they were to have accomplished exercise for most days of the week in a range of situations in the last seven days. The scale is a 5-point Likert-type ranging from 0 = “Not sure I could do it” and 5 = “Sure I could do it”. The reported internal consistency of the scale was 0.72 on Cronbach’s alpha scale. Perceived Barriers to Physical Activity ScalePerceived personal barrier to PA was assessed using 14 items scale developed by Tergerson et al, [23]. The 4-point Likert scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The barrier component of the EBBS which could be used separately as described by the authors, consists of 14 items which was rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale. Respondents were asked: "how important is each of the following in keeping you from participating regularly in physical activity?" The barrier component comprised 14 barrier items categorized into four subscales: exercise milieu; time expenditure; physical exertion; and family discouragement. The minimum score for the barrier scale is 14 indicating less perceived barriers to physical activity while the maximum score is 56. The reported internal consistency of the scale was 0.76 on Cronbach’s alpha scale. Both ESE and EBBS scores were transformed by calculating thus; 100 x (observed score – minimum possible score)/ (maximum possible score – minimum possible score) [24]. The 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles were used to label the transformed-scores into lower, middle and upper quartiles representing “low”, “medium” and “high” levels of self-efficacy and perceived barriers respectively.

2.3. Data Analyses

- Descriptive statistics of frequency and percentages was used to summarize data. Physical activity level as dependent variable was dichotomized as sufficient and insufficient PA. The associations between socio-demographic, psychosocial (self-efficacy, perceived barrier and parental SES), variables, gender and PA was determined using logistic regression with Odd Ratio (OR) at 95% Confidence Interval (CI). ORs with 95% CIs were calculated against the reference category of respondents aged 16 to 20 years, female gender, those who were in year 1 - 3 year of study, those with low self-efficacy, low socio-economic status and minor perceived barrier. Spearman rank correlation test was also used to determine the associations between PA and each of perceived barrier to PA items. Alpha level was set at 0.05. Data analysis was carried out using STATA-SE version 13.0 software (STATA Corp, Texas, USA).

3. Results

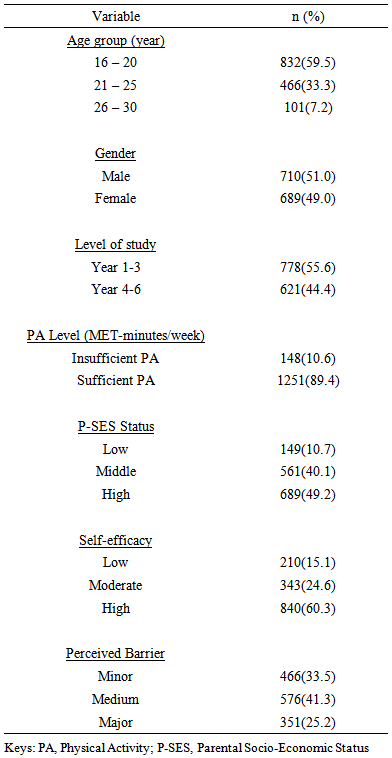

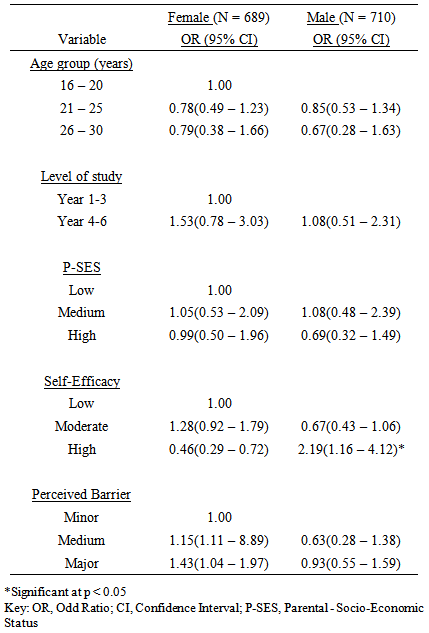

- One thousand three hundred and ninety nine respondents (males, 710 (51%); females 689 (49%) completed this study. Respondents whose ages ranged between 16 – 20 years constituted 832(59.5%). A majority of the respondents, 1251(89.4%) reported sufficient PA. Almost half, 689(49.2%) were in high parental socio-economic class while more than half, 840(60.3%) reported high self-efficacy (Table 1). Table 2 shows comparison between male and female in sufficient PA category. PA pattern tend to be same in all age groups and both sexes. Both female (OR = 0.99, C.I. = 0.50 – 1.96) and male (OR = 0.69, C.I. = 0.32 – 1.49) respondents in high parental socio-economic class were less likely to have sufficient PA respectively. However, high self-efficacy was twice more likely in male (OR = 2.19, C.I. = 1.16 – 4.12) than female counterpart (OR = 0.46, C.I. = 0.29 – 0.72). Similarly, male were less likely to encounter major perceived barrier to sufficient PA (OR = 1.43, 1.04 – 1.97) than their female counterparts (OR = 0.63, C.I. = 0.28 – 1.38).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- This study assessed socio-demographic, psychosocial correlates of physical activity among Nigerian young adults. A majority of the respondents in this study were found to have sufficient physical activity. The percentage of sufficient physical activity in this study is higher than the one reported (28.4%) in a similar study by Tumusiime and Frantz [25] among tertiary institution students in Rwanda. The variation in physical activity in this study compared to that of Tumusiime and Frantz could be attributed to the fact that household activities were not included in their study. Furthermore, methods of assessment of PA could also contribute to the difference observed in the present study. The present study found that pattern of PA between male and female is similar. This is contrary to the findings of previous studies which reported higher PA level in male than female [26, 27]. Also, in Nigeria by Adegoke et al, [28], male students have been previously reported to be more physically active than female students. However, recent study among university undergraduates by Adedoyin et al, [18] reported similar PA pattern in both sexes. This could be attributed to rigorous academic activities and well-designed environment such as walkways and recreational facilities within the university. This study revealed that PA was not significantly associated with parental socio-economic status among university undergraduates. There are mixed reports on the impact of parental SES and participation in PA. While some researches indicate variation between SES and PA participation [29], other research shows no significant correlation between socioeconomic status and PA patterns [30]. However, another study showed that socio-economic status was implicated with higher PA level [31]. It is possible that methods of assessing SES in different studies could contribute to the variations in the reported findings. Although, salient indicators of SES were included in the assessment, yet cultural background and environment might play significant role in the accurate determination of SES. For instance, from the Nigerian cultural stand-point, it is opined that most of the respondents might not be privy to the actual monthly income of their parents. Furthermore, education or occupation status of the parents alone may not be an independent measure of socio-economic status due to rate of poverty and unemployment in the country. Therefore, findings of this should be interpreted with caution.Self-efficacy was significantly associated with sufficient PA. This is in line with findings of previous studies which reported a significant direct association between physical activity and self-efficacy [32 - 34]. The pattern reported in those studies indicated that low self-esteem was associated with low PA. Robbins et al, [35] investigated self-efficacy among 77 adolescent girls and noted lack of self-efficacy was prime reason for physical inactivity. Belief in one’s ability to participate in PA, exercise self-efficacy, is a psychological construct that has had a documented impact on PA [36]. Sidman et al [36] further reported that the university provides a valuable opportunity for facilitating the knowledge, skills, and beliefs that develop healthy behaviours to last a lifetime. Self-efficacy as a personal attribute contributes to increased self-esteem and ability to task up challenges that may improve healthy lifestyle such as PA. Furthermore, university students are known to have access to information on healthy behaviour which may enhance good confidence including regular PA. Barrier factors to PA are believed to differ from one setting to another [37]. Lack of time was found to be the major barrier to PA among respondents. The finding of this study corroborates some previous studies that the most frequently reported barriers among youth were listed as: “I don’t have time”, “I’ m too tired” and “exercise doesn’t interest me” [37-39]. This may be due to the burden of academic and other extracurricular activities on the students. Expectedly, the result of this study is similar to the earlier studies [39-41]. However, studies among sedentary/ inactive young adults showed that lack of motivation and fatigue were widely cited barriers to PA participation [38, 42]. Our study has some limitations; first, PA level was assessed using a self-reported/subjective method which could have resulted in overestimation by the respondents. Secondly, this is a cross sectional study which may limit its external validity as the young adults within a university setting may not be representative of young adults in general. There is need for future research to use objective assessment of PA with larger sample groups in order to validate the result of this study. Furthermore, it may be helpful to identify perceived barriers to PA among other populations in Nigeria.

5. Conclusions

- A majority of the surveyed Nigerian university students reported sufficient levels of physical activity involvement over the course of seven days. Perceived exercise self-efficacy was significantly associated with high physical activity while perceived barriers, parental socio-economic status and gender were not. Reducing barriers and encouraging regular participation in physical activity among young adults may help to lessen the burden of chronic non-communicable diseases in sub-Sahara Africa.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors wish to thank the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA) for providing technical support. CARTA is jointly led by the African Population and Health Research Center and the University of the Witwatersrand and funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK) (Grant No: 087547/Z/08/Z), the Department for International Development (DfID) under the Development Partnerships in Higher Education (DelPHE), the Carnegie Corporation of New York (Grant No: B 8606), the Ford Foundation (Grant No: 1100-0399), Swedish International Development Corporation Agency – SIDA (grant: 54100029), Google.Org (Grant No: 191994), and MacArthur Foundation Grant No: 10-95915-000-INP.

Disclosure

- The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML