-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2014; 4(1): 14-20

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20140401.03

Importance of Efficacy in Achieving Coaches’ Success in Football. A Perspective from Elite Athletes and Coaches

Daniel Duarte1, Júlio Garganta2, António Fonseca2

1Research Centre in Sports and Physical Activity, Maia Institute of Higher Education, Maia, 4475-690, Portugal

2CIFI2D, Faculty of Sport, University of Porto, Porto, 4200-450, Portugal

Correspondence to: Daniel Duarte, Research Centre in Sports and Physical Activity, Maia Institute of Higher Education, Maia, 4475-690, Portugal.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The relevance of the coaches’ actions in the development of the sport training process enhances the need to more specifically understand the determinants of their efficacy. With the purpose of studying the efficacy of the football coaches in high-performance football it was used the CESp[2], an adapted version of Coaching Efficacy Scale (CES; Feltz, Chase, Moritz and Sullivan[1]). Participated in this study 244 players and 38 football coaches of the Portuguese Professional Football Leagues. The analysis of results showed there was an agreement between coaches and players on the order of importance of the considered factors, being motivation the most important one. It was also found convergence between the factors indicated as more important by coaches and the behaviours they use to adopt in their practice, as well between the evaluations made by players to the same factors and the correspondent behaviours perceived by them as the more frequently adopted behaviours by their favourite coaches. The conclusions resulting of this study should be considered as an asset in coaches training and consequently, in their performance, contributing to a better understanding of the efficacy factors to be stressed across the training process.

Keywords: Football, Coach, Player, Efficacy

Cite this paper: Daniel Duarte, Júlio Garganta, António Fonseca, Importance of Efficacy in Achieving Coaches’ Success in Football. A Perspective from Elite Athletes and Coaches, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 14-20. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20140401.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The emergence of a new wave of Portuguese coaches (three in the top five in 2011), with clear results in world football seems to stress the importance of research on high performance coaches, to better understand the role of efficacy in coaches’ success. The efficacy is one of the aspects that mostly influence coaches’ effectiveness[1, 3, 4] and, therefore, their success, as the maintenance of an effective practice that allows them to accomplish the proposed goals. Moreover, efficacy of the coaches is presented as a strong predictor of the efficacy of their teams and players[5]. Concerning this, Horn[6] even refers that the coaches’ effective behaviours provide a positive psychological impact and, consequently, improve a successful performance of their athletes.According to Kowalsky, Edginton, Lankford, Waldron, Roberts-Dobie and Nielsen[7] one of the most important aspects in the efficacy of the coaches’ action is the perception of the confidence in their ability to influence the learning process and performance of the athletes towards success, what Feltz et al.[1] designated as self-efficacy. In other words, self-efficacy is considered to be the confidence the coach shows in developing a competent behaviour[8]. Thus, to Feltz et al.[1] the efficacy of the coaches’ behaviours is conditioned by the confidence shown when successfully developing their tasks, being for that decisive the mastery of the specific skills. In this line of thinking, Feltz et al.[1] presented a conceptual model for the study of the coaching efficacy, which resulted in the development of an efficacy evaluation scale, the Coaching Efficacy Scale (CES), with a multifactorial base. According to the mentioned authors, the factors this model considers to be fundamental in the coaching action are motivation, game strategy, technique and character building; being noticeable in the same study the existence of a group of efficacy sources, namely coaching experience, previous success, the perception of the athlete’s ability and the support of the school/community. The motivation refers to the coaches’ capacity to influence the athletes’ skills and psychological condition and strategy represents the coaches’ skills in promoting a successful performance of their teams during competition. Technique corresponds to coaching skills in diagnosing and providing instruction during practice; whereas, character building relates itself to the coaches’ beliefs in their capacities to promote athlete’s personal development and positive attitude towards sports. From these, motivation and character building may be placed amongst coaching psychological skills. Game strategy and technique are related to coaching technical skills. The acknowledgment of coaching efficacy as a multifactorial measure resulted in many studies in this area; for instance, it’s possible to enhance the studies of Myers, Wolfe and Feltz[4], Fung[8], Boardley, Kavussanu and Ring[9], Campbell and Sullivan[10], Chase, Lirgg and Feltz[11], Feltz, Hepler and Roman[12], Myers, Feltz, Maier, Wolfe and Reckase[13], Kavussanu, Boardley, Jutkiewicz, Vincent and Ring[14], Sullivan and Kent[15] and Thelwell, Lane, Weston and Greenless[16]. However, at this moment there aren´t, practically, any researches of this nature in non-English language and specifically in what concerns to the football, we only know the study of Kowalsky et al.[7] carried with young football coaches in USA.Moreover, some of the constraints in the study of coach efficacy are related to the fact that most of these studies are dedicated to other sports as well as to young team coaches, particularly university[4, 11, 12, 15, 17]. Indeed, information from high performance coaches about that subject is scarce.A review of the available literature in this area also showed that most of the studies focused on the contextual validation of CES[1, 2, 4, 12, 18] in spite of also existing some researches focusing on the understanding of the factors of efficacy, its predictors and effectiveness[5, 14, 15], as well as driving programs of coaching efficacy.Also noteworthy, models of coaching effectiveness and efficacy tend to focus on the players perceptions of their coaches behaviours, enhancing its importance in this domain[6]. Indeed, Smoll and Smith[19], in a study about athletes’ perceptions of coaching effectiveness, found that the psychological impact of athletes’ participation in sports was related to the memory and perception of their coaches’ behaviour. So, it seems that one of the most important constructs when determining efficacy is the perceived efficacy, being recurrent its evaluation based on coaches and players opinion, as suggested in many studies[11, 20, 21, 22].Nevertheless, in the reviewed studies it is not given great relevance to the importance that coaches attribute to each of the efficacy factors or to the reasons that lead to the prevailing usage by them of certain skills in order to achieve success in sports. One emphasizes that coach’s self-perception of skills is a fundamental tool when determining the most important skills in coaching[23], and for this reason be worthy of study. However, at best of our knowledge, there isn’t any existent study that analyses the relationship between athletes’ and coaches’ perceptions and evaluations of efficacy factors and the way they are applied and developed in practice. Indeed, in a similar context, we could only find a research of Cunha, Gaspar, Costa, Carvalho and Fonseca[24] related to the image associated to the coach and the perception of characteristics of a good coach. In this study, as characteristics of a good coach there were emphasized aspects as: an adequate relationship with the players, the implementation of appropriate methodologies, planning, knowledge diffusion and the understanding of athletes’ characteristics. In this domain, we consider that one important aspect for the optimization of the relationship coach-athlete certainly is the knowledge of the athletes’ perceptions of their coach, particularly concerning personality characteristics and behaviours that players most value[25]. In this way, Feltz et al.[1] seek to relate the perception of coach’s efficacy to the level of athletes satisfaction, having been used a scale to evaluate this level of satisfaction. This study revealed that coaches with higher rate of efficacy produce higher rates of satisfaction in athletes. For these authors, the coach’s efficacy makes athletes more confident and motivated, enabling a higher performance and more fair play. Thus, it is important to understand the most valuated factors by the coaches, as well as their behaviours in practice, taking into account that valuation.Taking into consideration the impact of athletes’ motivation and satisfaction in their performance, it is relevant to know athletes perception of factors they most valuate in their coach’s action, being useful the acknowledgement of the most important coach in their sporting careers as he/she might be the one who promoted higher rates of satisfaction in the athlete. In this context, Steward and Owens[26] refer the players’ favourite coach is, normally, the one who promotes a higher level of support, does not criticize athletes and is creative and enthusiastic when working with players, individually or in a team. Therefore, the analyses of the players’ favourite coach will allow a more consistent understanding of the players’ most valuated factors, as the comprehension of their expectations permits the proximity of the coach in the correlation coach-athlete, and may enable higher performance rates. Actually, for Horn[27], the athletes’ attitude, their self-perception and their performance are influenced and mediated by the expectations they have about their coach. So, the knowledge concerning the way athletes create impressions and expectations may allow the coach to use their behaviour as a positive tool in the process development. In this extent, Lyle[28] even considers the coach should seek to adapt to the players’ daily expectations, in practice and in competition.Hence, the present study aims to contribute to the understanding of the importance that efficacy assumes in the success of high performance coaches, exploring the analysis of elite athletes and coaches’ perceptions of efficacy factors and its comparison with its implementation in practice by coaches. It’s also stressed the importance of acknowledging athletes’ expectations and perspectives through their perceptions of the most valuated factors by their favourite coach.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- The sample of this study was composed by 244 male players (with ages ranging between 18 to 35 years old, and an average professional experience of 8 years, varying between 1 to 17 years) and 38 male coaches (with ages ranging between 24 to 57 years old, and an average professional experience of 11 years, varying between 1 to 29 years), all participating in the Portuguese First and Second professional football leagues. Therefore, it’s possible to consider it as a sample of elite coaches and athletes, since the Portuguese Football League is amongst the ten best leagues in the world.

2.2. Instrument

- To collect the data it was used an adapted version, to the Portuguese language and culture, of the original Coaching Efficacy Scale developed by Feltz et al[1], named as CESp[2]. The CESp is an instrument previously validated to be used with people like the one used in this study, with good psychometric properties and acceptable fit to the proposed four factor structure used in this study[2]. The CES is a multifactorial scale in which each dimension is taken into account according to a group of items: i) the motivation dimension includes items such as “maintain confidence in the athletes performance”, “psychologically prepare athletes to the game strategy”, among others; ii) the strategy dimension comprises items as ‘identify the strong points of the opponent team” and “dominate strategies to use in competition”; iii) the technique dimension involves items as “individually train athletes’ technical aspects”, “ identify individual and team mistakes”, among others; and, finally, iv) character building dimensions contains items as “promote a good character attitude” and “promote fair play”.Hence, instruments presented the same items for athletes and coaches, being the initial question different according to the aims of the study. Therefore, in the first instrument filled in by coaches and athletes the initial question was “In your opinion, what is the importance of each of the following factors for a successful coach?” In the second instrument, the initial question to athletes was: “Think about the best coach you have worked with and refer how frequent he would adopt each of the behaviours or postures stated below”; but to the coaches that initial question was changed to: “Now state how frequently you adopt each of the behaviours and postures stated below.” To answer the different items contained in the instruments coaches and athletes used a 5 categories Likert scale, as suggested by Myers et al.[4] in studies of this nature. So, in the first instrument they used a scale of importance, in which 1 was considered "not important" and 5 "totally important." In the second instrument was used a scale of frequency, related to the behaviours adopted by coaches, in which 1 was considered as ‘never’ and 5 as ‘always’. Similarly to it was found in a previous study also carried with football players[2], Cronbach alphas showed good reliability of the CES Portuguese version used in this study, being above .70 (i.e., ranged between .71 and .79). Moreover, the inspection to the item-factor matrix correlation revealed in all cases positive and moderate to strong correlations, also supporting the quality of the used instrument.

2.3. Procedures

- The goals of this study were previously presented to athletes and coaches, having been assured confidentiality of their answers. It was also explained to athletes that we did not seek for an evaluation of their coaches, but for the understanding of their items’ evaluation for a better coaching performance. All team members, in the presence of the first author of this research, simultaneously filled in the instruments for a period of 10-15 minutes. The data collection was gathered, in the majority of cases in the facilities of the athlete and coaches’ respective clubs, except for when they were in a concentration period attending a game; in those few cases, they filled in the instruments in the facilities of the hotels where they were concentrated.

2.4. Data Analysis

- Data from the filled in instruments were firstly read by optical reading procedures and later statistically analysed through SPSS software, version 20, adopting a descriptive analysis (mean and standard deviation), inferential (independent measures t-test) and correlational (Pearson’s coefficient) of all studying variables. Considering the different size of the athletes’ and coaches’ samples, were performed previously independent samples Mann-Whitney U tests that showed no significant differences (p>.05) between the distributions of the answers of two samples across all the variables included in this study.

3. Results

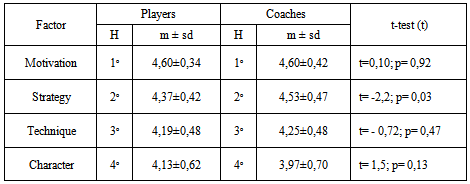

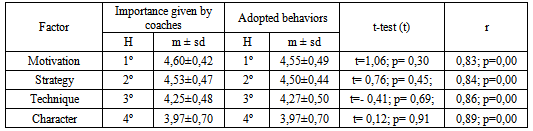

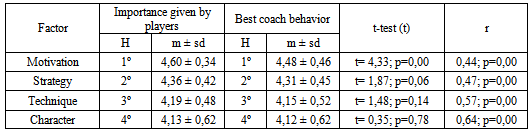

- The comparison of the importance assigned to the different efficacy factors by coaches and players showed that both find all of the four factors as important. Moreover, it was also evident that both coaches and athletes considered as the most important the motivation and strategy factors (Table 1).

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- When comparing coaches and athletes perspectives about what is more important for coaches achieving success, we identified similar judgments in evaluating the different efficacy dimensions, standing out the priority for psychological or motivational factors, with the character building presenting minor relevance in its performance. The higher valuation of psychological or motivational aspects, by coaches and athletes, converges with the importance given by the literature[29, 30, 31]. Weinberg, Grove and Jackson[32] stress that coaches’ efficacy should mainly be concentrated in athletes’ motivation. Therefore, the view of elite athletes of the Portuguese football should be taken in consideration, reinforcing the relevance of psychological factors in the success of the football coach[33, 34].Still, Feltz et al.[1] in their work with basketball coaches reported a high confidence of the coaches in the domains of strategy and technique, being motivation and character building the dimensions in wich coaches weren’t so confident in their application. On the other hand, Fung[8] concludes that coaches feel they are more effective in building character rather than strategy issues.Taking into account these results it seems interesting to deepen this research in football, in order to better understand the influence that knowledge and context may have over the coaches’ confidence to act in all of those domains, as well as to understand the way their confidence correlates with the importance they attribute to each of them. Indeed, Abraham, Collins and Martindale[35] refer that the acquisition of knowledge is related to the development of professional skills, which present themselves as the foundation of a competent coach.The congruence of perceptions among coaches and elite players on this study showed the importance of considering the players expectations, namely on a psychological level. Furthermore, Myers et al.[13] reveals the coach’s motivational competence has a positive and close relation with the athletes’ satisfaction degree, facilitating the achievement of success. In this context, it seems to be important to recall the results of Curtner-Smith, Wallace and Wang[36] and Riemer and Chelladurai[37] wich indicate that athletes’ satisfaction is greater when there is congruence between the perception and preferences of both, in the psychological level, in particular in the dimension of social support. Boardley et al.[9], in a study with Rugby coaches, added that efficacy in the psychological aspects powers the positive reinforcement and the athletes’ commitment. Based on this new line of thinking, we believe to be relevant to understand if the emphasis in the psychological factors is a trend in the football training, justifying an analysis on the international elite of football coaches in order to frame the results of this study in broader perspective.This research allowed also to identifying positive and strong correlations between perceived coaches’ behaviours and the importance assigned to the correspondent efficacy dimensions, emphasizing once more the need to be coached through specific and systematic programs. In this sense Martens[38] points that it’s the acquired knowledge on a modality which will support the teaching of its procedures, revealing a necessary complementary theoretical and practical. Jones, Armour and Potrac[39] state that the coaches’ knowledge is related with the rationalization of their behaviours both in sport and social levels, adding that a coaches’ specific knowledge is fundamental in the athletes’ appreciation and development. Moreover, the link between what the coach value and his practice reveal the necessity which the coach presents in the acquisition of a body of knowledge, as advocated by Martens[38], as well as in the improvement of these through the process of specific training, creating innovative solutions in solving his problems, as advised by Salmela and Moraes[40]. Malete and Feltz[17] also confirmed the effect that a coaches’ training program in the efficacy is significant, especially in the character building dimension. So, we defend the need to adopt a specific training program that enables and facilitates the application of the assumptions inherent to the dimensions they most value, suggesting a deeper study regarding the orientation of the existing programs, seeking to realize if they are related to the efficacy factors of the coach.It is clear that the most valued factors by the athletes converge with the adopted behaviours by who they believe to be their best coach, which can be explained by the result found by Vargas- Tonsing et al.[5], who notes a close connection between the coaches’ and the players efficacy. In other words the player perceives as the most effective coach the one that leads or led him to best efficacy rates. The favourite coach is the one that promotes a high level of support, doesn’t criticize the athletes and is creative and is enthusiastic when working individually or working in team. Still, the coaches’ influence on his athletes is potentiated by how they relate to him, namely concerning the understanding of the coach’s feelings and emotions triggered by the competition[41]. Moreover, this sustained compliance by a positive correlation in all the analysed factors, allows us to speculate that the athletes consider to be their best/ favourite those who fulfilled and closest got to their expectations, which are fundamental for the player’s satisfaction and depend on the proximity, knowledge, adaptation and comprehension of each group of each individual, by the coach[31, 42]. For instance, Marcos, Miguel, Oliva, Alonso and Calvo[43] in a study with footballers expectations, concluded that the level of efficacy and cohesion diminish when the expectations are not fulfilled.In the training process the proximity towards the appreciation of the efficacy factors between coach and player may constitute an advantage since it develops a positive relation which provides a committed and motivated participation of the athletes, boosting their performance towards the achievement of the teams aims and consequently its success. The coaches’ efficacy has a strong influence on the player’s efficacy, in their performance, in their satisfaction[1] and in team’s efficacy[5]. In this context it is noted an esteemed by athletes the psychological aspects when considered their perception about their best coaches. This result emphasizes the importance of giving more attention to the psychological aspects, contradicting what, according to Henschen[44], is the current coaches’ tendency to overvalue the technique dimension, mainly in competition. The psychological dimension was neglected for years, as a result of the interpretation of the coach’s relation to his athletes as a question of character, naturally inducing its depreciation, particularly from the leaderships’ point of view[45]. However Sullivan and Kent[15] results, which approaches the style of leadership and efficacy, in particularly to the level of motivation and technical ability, suggests that the factors valued by the coaches’ are those which characterize his leadership as a coach.

5. Conclusions

- The results of this suggest that coaches’ efficacy depends on the combined action of numerous factors. Also the valuation of certain efficacy dimensions over others without the knowledge of the athlete’s expectations may compromise the outcome of their actions and naturally their success. Accordingly, the results of this study reveal that coaches’ most valued the motivational dimension, enhancing the importance coach should attribute to it during the training process.This study also showed there is a positive and strong correlation between the importance given by coaches to the different dimensions and the way they act on the field. Surely the systematization of a body of knowledge about the application and the appreciation of the psychological and technical skills take on a fundamental assumption in the performance, mainly in conducting his athletes. Otherwise the ritualization of behaviours and actions by the coach may, in some situations, be effective and in others not, conditioning his success.There is still an agreement between the dimensions that players most treasure and their perceptions about the actions of who they considered to be their best coaches ever, enhancing a close relationship between the athletes’ and coaches’ perspectives about what is more important in the field and stressing the importance of taking in consideration the athletes expectancies about that in the development of their training process.Despite this study’s results appear to be relevant regarding its application to the Portuguese football context, it should be underlined that its transference to other realities can be limited, taking in consideration the necessary methodological adjustments according to the type of sport, country, gender and samples’ competitive level. It is also important to add that this study is based on the athletes and coaches’ perspectives and perceptions and not in the real coaches’ behaviours. On the other hand, the fact that this study was carried in one of the greatest impact worldwide sports and the quality of its sample (elite coaches and players of the professional Portuguese football leagues) constitute two of its strengths. In short this study aims to stimulate a greater interest on the factors that contribute to the coaches’ success but further research is suggested, especially in what concerns to the practical application of these factors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML