-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2013; 3(6): 233-240

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20130306.09

Beyond BIRGing and CORFing Tendencies: Effects of Identification with Foreign Football (Soccer) Teams on the Mental Health of Their Nigerian Supporters

1Department of Psychology, Federal University, Ndufu-Alike, Nigeria

2Department of Sociology/Anthropology, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Fabian O. Ugwu, Department of Psychology, Federal University, Ndufu-Alike, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Earlier studies demonstrated that individuals’ identification with successful or unsuccessful local sport teams have implications on their social well-being and psychological health. The current study moved a step further to examine the mental health implications of sport viewers’ identification with foreign football teams in two separate studies. Study 1 revealed that individuals reported better mental health following their team’s game win, and poorer health following game loss. In study 2, high identifying individuals reported better and poorer mental health compared to low identifying persons following their teams’ victories or losses respectively. Males reported better and poorer mental health compared to females following game victories or losses respectively. Results suggest that successes or failures of foreign football teams have health implications on their Nigerian fans.

Keywords: BIRGing, CORFing, Identification, Foreign Football Teams, Mental Health

Cite this paper: Fabian O. Ugwu, Chidi Ugwu, Beyond BIRGing and CORFing Tendencies: Effects of Identification with Foreign Football (Soccer) Teams on the Mental Health of Their Nigerian Supporters, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 233-240. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20130306.09.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- People like to flaunt their association with successful others even if they are not successful themselves. They have a reputation to partake in the joy of victory but refrain from the agony of defeat. It is the former that[1] referred to as the tendency to Bask-in-Reflected-Glory (BIRG): individuals’ desire to broadcast their association with successful others. The latter lead to what has come to be known as Cutting-Off-Reflected-Failure (CORF)[2], a tendency to dissociate oneself from unsuccessful others. Researchers have observed that the tendency to CORF is more dominant than the tendency to BIRG[3]. The top English football clubs have a long rich history. Within England, these teams have very good reputations. To them and their supporters winning is a norm and losing is majorly not an option, but in every sport competition there are good and bad times. Loss of an important game is often unacceptable if not traumatic. It thwarts the supporters’ expectation, and it has been observed that thwarted expectations were a necessary condition to elicit CORF[4].[3] added that it is only during defeat that people would dissociate themselves from the source of failure. But among these supporters in Nigeria, there is often a show of rare enthusiasm to these foreign teams, and so, many football fans rather than CORF strive to remain steadfast with their teams in defeat.It is understandable however for individuals to bask in the glory of successful others when they played a significant role in ensuring the achievement of that success or when they are connected with the successful others[1]. But what is rather strange and which seems to defy models of rationality is when individuals bask in the glory of successful others when they neither played any role in the attainment of that success nor are connected in any way with the successful others. This is difficult to understand in that there has not been any clear-cut benefit associated with such behavior[5]. Although the social identity theory[6] has attempted to justify this mass behavior, it may not have adequately explained such ‘group madness’ that now characterize the Nigerian society with regards to foreign football clubs. The objectives of the present study which was conducted in two waves were to investigate whether foreign football clubs’ games outcome will have any significant effect on the mental health of their Nigerian supporters (that is, study 1). Study 2 examined whether some dispositional or personal variables such as sport team identification and gender will predispose an individual supporter to experience better or poorer mental health following their teams’ game outcome.Of all the football leagues in the world, the English Premier League (EPL) seems to be the most followed and has the support of greater percentage of Nigerian football lovers to the detriment of Nigerian Premier League (NPL) that has been largely isolated. The EPL has gained such elemental passion in that majority of Nigerians irrespective of gender, age, ethnic group, occupation and status have developed strong emotional attachment towards these football clubs that are alien to Nigeria. The game of football played in a foreign country has indeed become the nation’s obsession which can be exemplified by people relegating their economic activities to the background just to watch football matches on television. The height of this behavior is that Nigerians troop to different sports viewing centres with variety of musical instruments to cheer up their teams playing on television. Moreover, the supporters’ personal items have insignia to indicate the clubs they support. For example, official vehicle plate numbers are now personalized such as AR 4 LFE, which stood for ‘Arsenal for life’, a slogan often used by fans of Arsenal football club to proclaim their allegiance and solidarity. Fans of different football clubs go to churches a night before a crucial game to book mass requests for the success of their teams. More still, at the end of every football season in-group fans organize themselves and take turns to give thanks to God in churches for successes achieved the past season and to ask for His favor the coming season. Such fans find it difficult to carry out their normal functions such as attending lectures or opening their shops for business in a morning following their teams’ defeat. Such obsessive behaviors towards foreign football teams in Nigeria have become a central part of many people’s lives and arguably a central part of their culture. Individual supporters with such strong support or affiliation with their teams could experience some changes in their mental health status following their teams’ game outcome. It is therefore proposed that:Hypothesis 1a: Foreign football teams’ game win will have a significant positive effect on the mental health of their Nigerian supporters.Hypothesis 1b: Foreign football teams’ game loss will have a significant negative effect on the mental health of their Nigerian supporters.One variable that has been strongly related to sport is team identification[7]. Sport team identification is the extent to which a fan feels psychologically connected to a team[8].[9] showed evidence that level of identification with a local team is positively related to psychological health.[7] found that higher fan identification led to an increase in tendencies to BIRG and lowered tendencies to CORF.[10] reported that identification with a group has important implications for self-esteem, and the degree of the consequences for the self, differs across groups.[11] found that persons with high levels of team identification reported higher level of vigor and self-esteem, and lower levels of confusion, anger, fatigue, depression, and tension compared to their counterparts with low identification.[12] found that higher levels of identification were associated with greater levels of satisfaction with one’s social life, was positively related to total social well-being[13], personal self and collective-self-esteem[14;15], personality[16]. Also it also seems to provide individuals with a more positive view of others, which is a dimension of well-being[17; 18]. High identifying fans experience greater arousal and anxiety during a sporting event[19].[10] argued that esteem needs is not implicated where people lack a strong identification with the group. Therefore, fans at sporting events are aware of the evaluative implications of their team’s performance and can experience the joy of victory or agony of defeat as intensely as the participants[20]. Several authors (e.g.,[7; 16; 13]) have extensively investigated the implications of sport team identification, most of their studies used local teams and largely focused on the social aspects of well-being (e.g., loneliness, anger, personal self-esteem, collective self-esteem), psychological health (e.g., stress, depression), and personality (e.g., extraversion, openness and conscientiousness). However, none of those authors directed research effort at the mental health of viewers’ identification with foreign football teams. The current investigation was therefore designed to shed more light on this area of study by adopting the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), a robust instrument that focuses on two major areas – inability to carry out normal functions and the appearance of new and distressing experiences to assess the mental health status of individual supporters that watch foreign football teams on television. The researchers are not aware of any of such study in Nigeria or elsewhere.[7] asserted that because identification with a particular team is so central to individuals’ identity, highly identified persons are likely to maintain their allegiance against all adversity, but might pay a huge price. They tend to suppress their emotion, which may in turn lead to the experience of some mental health problems. The present researchers think that while basking in reflected glory emphasizes the association-enhancing tendency and failure decreases the association, all for the sake of maintaining self-efficacy and balanced life, it makes a theoretical as well as empirical sense to propose that individuals high in identification with foreign teams may experience better mental health when their teams are victorious and are likely to experience poorer mental health when their teams suffer defeat. It is on this basis that it was hypothesized that:Hypothesis 2a: Individual supporters high in team identification will report better mental health scores following their team’s game win relative to their counterparts low in team identification. Hypothesis 2b: Individual supporters high in team identification will report poorer mental health scores following their team’s game loss compared to their counterparts low in team identification.Watching the game of football is not peculiar to Nigerians. The rate at which the game attracts people all over the world has reached alarming stage. This was once seen as men’s affair as sport was translated into men being the sources of knowledge and authority to watch and discuss it.[21] captured this when they asserted that women, with vast experience and a lifetime of watching sport, were deprived the opportunity to discuss sport. Today, the story is different. Women football viewers and fans have continued to increase. However, several studies have examined motives and behaviors of male and female sport fans. Most of these studies anchored on sport fan motives because different motives fulfil social and psychological needs of the fan[22]. Thus, such fans will differ relative to what social and psychological needs they have, their motives for watching will correspond with those needs[21]. They will also differ on the impact that being an avid fan of a particular sport team will have on both genders due to the performance of their teams in competitions.Gender is related to how we are perceived and expected to think and act as women and men because of the way society is organized, and not because of individuals’ biological differences[23].[24] stated that gender-based differences in mental health may emanate from biomedical, psychosocial, or epidemiological factors. Contrary to most previous studies on gender differences in mental health that focused on individual level influences, such as socio-economic status, socio-demographic history or social support,[25] and[26] emphasized the importance of social context on the onset and development of psychopathologies, such as depressive symptoms. One of the social contexts that may lead to mental health challenges, is one’s allegiance to sport teams in that games’ outcome of their team may affect them significantly irrespective of whether they are males or females. Previous studies (e.g.,[27; 28]) suggest a substantial correlation between the mental health of spouses although wives score worse on indicators of mental distress than husbands.[29] study showed that although the mental health of couples was correlated, wives had poorer mental health than their husbands.[30] and[31] found that women had a higher prevalence of most affective disorders and non-affective psychosis, and men had higher rates of substance use disorders and antisocial personality disorder. In a cross-sectional survey,[32] found that boys reported more sources of stress than girls and also showed more negative attitudes. Evidence from the previous studies showed some inconsistencies pertaining to gender and mental health status. It therefore makes sense to shed more light into this blurred area of study, thus the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 3a: There will be a statistically significant gender difference in the mental health scores of football supporters, such that males will report better scores than females following their team’s game win.Hypothesis 3b: There will be a statistically significant gender difference in the mental health scores of football supporters, such that males will report poorer scores than females following their team’s game loss.Study 1

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

- Two hundred and four (204) participants took part in the study. They consisted of 171 (83.82%) males and 33 (16.18%) females. Fifteen (7.35%) were university graduates, 141 (69.12%) were university undergraduate students, and 48 (23.53%) of them were secondary (high) school graduates. Their ages ranged from 19 to 41 years, with a mean age of 26.8 years. In the two-wave study, a total number of 249 of the GHQ-12 with specific instruction as regards their team were administered to the participants. The questionnaires were administered across 10 sports viewing centres in Nsukka, Nigeria by the researchers and 8 research assistants during the 2011/2012 season of the English Premier League. The study took place within the last ten football matches when any result is expected to define a club’s season, and when any match outcome is likely to play out on the supporters’ emotions. First, the participants completed the questionnaires before a football match (pre-test). Immediately after the match the same participants completed the same questionnaires (post-test). The researcher coded the pre-test to ensure accurate matching with the post-test for all the participants. These questionnaires were administered before a game win and after a game win, and also before a game loss and after a game loss. Out of the 249 copies administered, 231 copies were completed and returned, representing 92.77% response rate. Twenty seven (27) copies (11.69%) were discarded either because they were incomplete or because the researcher failed to match the respondents’ background information in the first wave to the second wave and only 204 copies were considered for data analysis. All the respondents for the study were volunteers. Each respondent was provided with a pen to enable them complete the questionnaires. This served as an incentive because they were informed before the study that after completion of the questionnaires the pens were not to be returned.

3. Instrument

3.1. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)

- The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), a measure of current mental health developed by[33] was used to measure participants’ mental health. It focuses on two major areas – the inability to carry out normal functions and the appearance of new and distressing experiences. The questionnaire was originally developed as a 60-item instrument, but now has a range of shortened versions including GHQ-12, and this has been shown to be as effective as the full (original) version. The questionnaire asks whether the respondent has experienced a particular symptom or behavior recently. Each item is rated on a four-point scale. Internal consistency has been reported in a range of studies using Cronbach’s alpha, with correlations ranging from 0.77 to -0.93. There is good evidence that clinical assessments of the severity of psychiatric illness are directly proportional to the number of symptoms reported on the GHQ-12[34]. The predictive validity of the GHQ in comparison with other scaling tests of depression is also good[35]. Split-half and test-retest correlations have been carried out with good results[34]. Studies have indicated that the GHQ-12 is a consistent instrument over multiple time periods with relatively long periods between applications in general population samples. Cronbach reliability alpha of .81 was obtained for the present study. Lower scores on the questionnaire indicate better mental health of respondents.

3.1.1. Study Design and Treatment of Data

- The design employed for study 1 was a repeated measures design, and the paired t-test statistics was utilized in analyzing the data.

4. Results

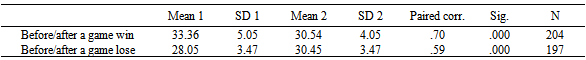

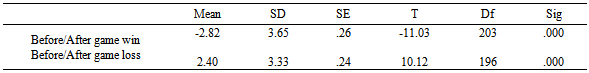

- Paired sample t-test results were shown in Table 1. It would appear from these results that the anticipated change in the mental health of supporters after a game win occurred. The mean for mental health scores was lower in the post-test (after a game win: M = 30.54) compared to (M = 33.36) in the pre-test (before a game win). The correlation coefficient (r = 0.70, p < .001) is statistically significant. This provides evidence that mental health status of supporters improved significantly after their team had won a game.The results as indicated in Table 1 also show that the anticipated negative change in the mental health status of supporters after a game loss was confirmed. The mean was higher in the post-test (after a game loss: M = 30.45) relative to (M = 28.05) in the pre-test (before a game loss). The correlation coefficient (r = 0.59, p < .001) is statistically significant, and provides evidence that the mental health of supporters worsened after their team had lost a game. The picture is repeated in Table 2, which displays results of the t-test for paired differences on both conditions. While before/after a game win show statistically significant positive change (t = -11.03, p < .001), before/after a game loss show statistically significant negative change (t = 10.12, p< .001). Accordingly, hypotheses 1a and 1b are supported.

5. Discussion

- It was hypothesized that foreign football teams’ game win will have a significant positive impact on the mental health of their Nigerian supporters, and that their game loss will have a significant negative impact on the mental health of their Nigerian supporters. The results of this study clearly lend strong support for these propositions. The participants showed better mental health scores following their teams’ victory (post-test) relative to before a game win (pre-test). Conversely, they also reported poorer mental health scores following their teams’ game loss in their post-test (before a game loss) relative to the pre-test (before a game loss). Based on these results, the team’s game outcome take on a significant impact as being a fan of foreign football teams has overwhelming health implications on their Nigerian supporters. This result seems to align with the assertion of[36] that the way individuals handle information about those associated with them is very similar with the way they do information about themselves, and any positive or negative effect such information may have on people associated with them might as well affect them. The social identity theory (SIT) could be used to explain this result. Research on SIT has indicated that there is often uncontrollable individual tendency to be biased in various situations in favor of groups they are affiliated to, such that they will rate their affiliated groups as better and unduly allocate resources to those groups even to the detriment of out-groups. If the individual’s group suffer any ordeal, its impact on the individual takes similar processes in the life of those affiliated to the group. It is established that success enhances the tendency to associate with successful others[1]. Reverse is also the case: people tend to decrease or isolate themselves from failure to protect their self-image. The result of this study went a step further to establish that a team’s game win and loss are not limited to BIRGing and CORFing respectively, but impact positively or negatively on their mental health.

|

|

6. Method

6.1. Participants and Procedure

- The participants for the study consisted of 240 football fans sampled across 12 sports viewing centres in Nsukka, Nigeria. One hundred and seventy four (72.5%) were males whereas 66 (27.5%) were females. Fourteen (5.8%) were postgraduate students, fifty three (22.1%) were university graduates, 134 (55.8%) were university undergraduate students, and 39 (16.3%) of them were secondary (high) school graduates. Their ages ranged from 21 to 44 years, with a mean age of 29.6 years. A total number of 288 copies of the Team Identification Questionnaire and the GHQ-12 were administered to the participants by the researcher and 11 research assistants during the 2011/2012 season of the English Premier League. The study was conducted within the last 7 matches of the season when any result is expected to determine the fate of any team in the league. Out of this number administered, 263 were completed and returned, representing 91.3% response rate. Out of this number 23 were discarded because some of them were not adequately completed or that the respondents failed to supply their demographic information, leaving the researcher with 240 copies used for analysis.

7. Instruments

7.1. Team Identification Questionnaire (TIQ)

- Participants completed the adapted version of a 7-item Team Identification Questionnaire (TIQ) designed to measure individuals’ level of sport team identification. Responses for the items were on 8-point Likert-type response formats. Previous researchers[7] revealed that the scale is reliable and consists of a single factor, and possesses predictive validity. The items were slightly modified by the present researchers to suit the current study. For instance, item that reads, ‘how strongly do you see yourself as a fan of the K. U. basketball team?’ was modified to read ‘how strongly do you see yourself as a fan of the Arsenal/ Chelsea/ Liverpool/ Manchester City/ Manchester United football team?’ Resulting reliability was α = .79. Also, the 8-point response format was reduced to three to make responses easier. The mean score was the basis of classification of the participants into 2 groups of high and low identification. The GHQ-12 used in study 1 to elicit information on the mental health status of the participants was administered together with the TIQ.

7.1.1. Study Design and Treatment of Data

- In study 2, a 2 (gender: male versus female) x 2 (level of identification: high versus low) factorial design was adopted, and the Multivariate (MANOVA) statistics was used for data analysis.

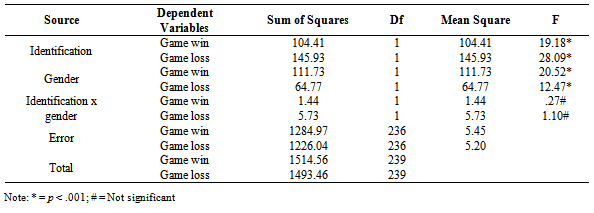

8. Results

- It was postulated that supporters high in team identification will report better mental health scores following their team’s game win relative to those low in team identification. The reverse was also anticipated that individuals high in identification will experience poorer mental health following their team’s game loss compared to those low in identification. It was also hypothesized that male supporters will report better mental health score following their team’s game win compared to their female counterparts. Conversely, male supporters will report poorer mental health scores compared to their female counterparts following their team’s game loss. To test these hypotheses a 2 (identification: high versus low) x 2 (gender: males versus females under game win and loss conditions were considered. The multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was computed and the output of this analysis is presented in Table 3 below.

|

9. Discussion

- The results of the study indicated that individuals high in identification reported better mental health scores following their team’s victory compared to those low in identification. Also consistent with anticipation, individuals high in identification reported poorer mental health scores following their team’s failure compared to those low in identification. This result is consistent with previous findings (e.g.,[14; 19; 15; 11]) which found that level of identification is positively related to personal self-esteem, frequency of experiencing positive emotions, higher level of vigor (i.e., energy), and lower levels of confusion, anger, fatigue, depression, and tension compared to their counterparts with low identification. The results also seem to be in agreement with that of[12],[13],[9],[17],[18] which established that higher levels of identification were associated with greater levels of satisfaction with one’s social life, positively related to total social well-being, correlated with psychological health, and also seems to provide individuals with a more positive view of others, which is a dimension of well-being. This study also investigated the differences in mental health status between male and female supporters of foreign football teams. Consistent with hypothesized gender differences, male supporters reported better mental health scores following their team’s victory compared to their female counterparts. Conversely, males also reported poorer mental health scores following their team’s failure compared to their female counterparts. This result is not strange in that male participants seem to be engrossed more in such male-dominated sport as football. Gender stereotype might be used to further explain this result. Researchers (e.g.,[36]) asserted that gender stereotypes can exert overbearing influence on cognition and behavior. It plays a role in many achievement-oriented domains, which may include sport. This might have affected the perception of female participants on football match outcome and might have made them less absorbed in the game. Although the result of the present study is inconsistent with many previous ones on mental health (e.g.,[27; 28; 31; 29]) all of which found that females reported poorer mental health than their male counterparts, the contexts in which these studies took place might have predisposed females to report poorer mental health than males. Hence, when the mental health of individuals is being studied, the context under which such study is taking place is critical and may need to be controlled. The results of this study moved beyond the two phenomena often witnessed in many social and political contexts, BIRGing and CORFing[1; 7; 3; 38], beyond social well-being and psychological health of local spectators to establish that high identification with sport teams can trigger off some psychopathology symptoms in individuals following their teams’ game loss. Rather than CORFing they are likely to have persevered with their teams in difficult moments and this die-hard spirit resulted in their poor mental health scores. Reverse was also the case; such highly identified individuals, although they are likely to BIRG, report satisfaction with social life and better psychological health. Based on previous studies, viewers of foreign teams’ games equally experienced improved mental health following their teams’ game victory. Moreover, although individuals low in team identification was also likely to CORF, they also experienced better mental health following their team’s game loss. It is obvious that low identified fans, which also can be referred to as fair-weather fans, are jolly good fellows who only share in the joy of victory, but hardly ever share in the agony of defeat. They easily swing to any direction the pendulum of success moves to protect their self-esteem. This justifies their better mental health score even when ‘their’ team lost a game relative to those high in team identification. This result implies that although Nigerians support of foreign football teams seems to have become contagious and widespread, when investigating such behaviors, it is worthy to note that all the supporters are not equally affected.

10. General Discussion and Conclusions

- The results of these studies moved beyond the two phenomena often witnessed in many social and political contexts, BIRGing and CORFing[1; 7; 32; 37], beyond social well-being and psychological health of local spectators to establish that participants with psychological connection toward foreign football teams often experience some psychopathology symptoms following their teams’ game loss. Rather than CORFing they are likely to have persevered with their teams in difficult moments and this die-hard spirit resulted in their poor mental health scores. Reverse was also the case; although such persons are likely to BIRG and reported satisfaction with social life and better psychological health based on previous studies, the result of the present study revealed that viewers of foreign teams’ games equally reported improved mental health following their teams’ game victory. Moreover, although individuals low in team identification was also likely to CORF, they also experienced better mental health following their team’s game loss. It is obvious that low identified fans, which also can be referred to as fair-weather fans, are jolly good fellows who only share in the joy of victory, but hardly ever share in the agony of defeat. They easily swing to any direction the pendulum of success moves to protect their self-esteem. This justifies their better mental health score even when ‘their’ team lost a game relative to those high in team identification. This result implies that although Nigerians support of foreign football teams seems to have become contagious and widespread, when investigating such behaviors, it is worthy to note that all the supporters are not equally affected.Also to draw inferences with such result might be problematic or erroneous. Future researchers should adopt multiple sources of data to cushion any undue influence such might have on results. In conclusion therefore, although previous studies found that people BIRG and CORF in different contexts following successes and failures, to maintain their self-esteem, enhance their social well-being or psychological health as previous studies established. The current study demonstrated that beyond these BIRGing, CORFing, social well-being and psychological health, successes and failures of foreign football teams also impact on the mental health of their Nigerian supporters.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML