-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2013; 3(6): 198-203

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20130306.03

Training and Professional Performance of Radical Sport Instructors

Jairo Antônio da Paixão

Department of Sports, Federal University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, 35400-000, Brazil

Correspondence to: Jairo Antônio da Paixão, Department of Sports, Federal University of Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, 35400-000, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Aspects related to the performance of professional radical sport instructors are herein analyzed regarding three detected educational levels: those who graduated in Physical Education, those whose diplomas are in other fields, and those who are high school graduates. By exploring available literature and considering the educational levels of these professionals, it was possible to verify discrepancies regarding the procedures adopted by these instructors in conducting the activities that constitute radical sports, sometimes creating situations vulnerable to risk. In connection with this, there is a need for the institutions responsible for these sports to standardize the requirements for the education and performance of radical sport instructors in Brazil.

Keywords: Radical sports, Professional education, Instructors

Cite this paper: Jairo Antônio da Paixão, Training and Professional Performance of Radical Sport Instructors, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 3 No. 6, 2013, pp. 198-203. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20130306.03.

1. Introduction

- The word – radical sport – has the connotation of sensations related to risks, adventure, and strong emotions. This is true for those who practice the sports, as well as for those who don’t, due to imaginary forces created by this type of sport[3, 4]. Those who practice radical sports, either for competition or recreation, put themselves at risk in different proportions, such as falls, collisions, scrapes and bruises, fractures, drowning, freezing and even death[12]. These risks occur because radical sports are designed for various types of atmospheres, which within possible reasoning, are forecasted and controlled. Thus, the outcome of the sport practiced can generally be successful. For example, a paragliding flight, the arrival at the top of a mountain, or even, the return from a dive performed in treacherous waters. Reality has shown that in some cases using sophisticated equipment is not sufficient to impede a serious accident. However, when the practice of a specific sport is coupled with procedures and strategies developed from knowledge of the sport module, there is a tendency to minimize accidents [12, 13]. As such, the participant should be equipped with a series of skills that include: physical intimacy with the equipment and necessary techniques, capacity to decipher information regarding climatic conditions, and when an unexpected event occurs, to be able to decide and act upon strategies to overcome the obstacle(s), successfully achieving completion of the chose trajectory. This knowledge should be sufficient to assure that the participant not only enjoys the adventure, but also maintains physical and emotional integrity, besides contemplating aspects regarding environment preservation for the sports module chosen. These considerations furnish elements for reflection about the type of instruction to be received by both learners and experienced participants. It is important that these people, who seek strong emotions and expose themselves to risky conditions, be assured that their instructors are competent in their field, minimizing the risks for everyone involved. In search of responses to these claims, by means of empirical observations and scientific production that approach this topic, it became evident that in Brazil there are no official requisites for a professional dealing with radical sports in comparison with those who deal with physical education. Usually radical sport professionals are self-taught and receive minimum knowledge through courses offered by some sport confederations or international certifying associations[3].Surely, this fact is justified by the actual circumstances of the issue. Although radical sports are a reality in terms of being physically practiced in Brazil, either for leisure or competition, discussions on the subject do not contemplate in any significant magnitude the matters and implications that this subject requires. According to Marinho, even though this branch of sports is being developed in Brazil in an innovative and promissory manner, unfortunately there are only a reduced number of researchers that try to optimize qualitative knowledge to assist and qualify the professional skills for those working in this area and as such, effectively contribute to the demands for information regarding radical sports and their calculated risks[11]. The picture presented so far circumscribes radical sports as an intervention of innovative professional teaching, thought provoking and full of possibilities, but still void of a professional profile for the conduction of these activities. Although the professional’s skills and competence are presented in a diffused manner, if compared with the status that other professional categories have, it is necessary to think about the dynamics established between these elements that constitute the teacher’s job[14]. As part of these dynamics, it is worth noting the need for technical preparation, teaching methods, and pedagogy for the contents to be worked when conducting activities related to a radical sport model. For this, the sport’s particularities, complexity and possibilities during the teaching process must be considered. Given that Brazil does not have a specific official formation for this type of professional, in this study, observations and surveys were made about practicing radical sports instructors and it was observed that this instruction is performed by different types and educational levels of people. What prevails is their practical experience in a given radical sport model. From this data, it was possible to distinguish three educational levels for the instructors: high school, university graduates in Physical Education and those graduated from the university in other fields. With this data, the objective of the study was to analyze the aspects related to the instructor’s professional performance in radical sports, using the three educational levels as a reference.

2. Materials and Methods

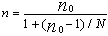

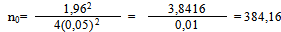

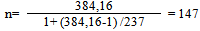

- The present study employs methodological procedures for an exploratory descriptive research[5, 10]. The line of research was to make a survey of available data[1, 8]. The elaboration and validation processes followed the Delphi technique[6, 16]. This technique involves emission of a series of questionnaires in such a way that a group of specialists (professors with experience in the area) come to a consensus about the subject through discussions about the matters involved in the questionnaire. The number of phases employed in the validation of the collected data varied from two to five or until each question received two-thirds affirmative replies[6, 9]. Using a succession of partners with three specialists in the area, a total of four phases, brought to the consensus in the investigative questions related to the education and professional performance of the instructor of radical sports, having as a reference the three previously mentioned educational levels. In this perspective, a semi-structured questionnaire was developed and applied to collect the necessary data. After compiling the number of federations existing in the State of Minas Gerais, information was also sought about firms specializing in radical sports that were associated with the State of Minas Gerais federation dealing with that specific radical sport. By means of telephone calls, emails, and information available on the sites of these firms, it was possible to achieve data about the instructors connected with them. It was found that the number of instructors for the firms associated with the State of Minas Gerais Federation is 237 and that they are responsible for conducting 19 types of radical sports. These firms are encountered in cities of different sized populations and demographic dimensions, including cities of small and large sizes in the interior of the State. To define the sample size, two values were employed. The success probability was fixed at 0.5 (with a 50-50 chance of success). Also considered was the confidence interval of 5%, whose intention was to assure a greater degree of precision. It was then possible to calculate the size of the sample by means for the following formula1: Where n0 is given by

| (1) |

| (2) |

As such, the sample size was:

As such, the sample size was: Where: N = population size; n = sample size; d = margin of error; z(k) = desired degree of confidence (using a confidence degree of 95%, which is equal to p = 0.05)Selection of the instructors to define the sample – 147 instructors – was done in a probabilistic manner, using the simplified stratigraphic sampling technique[2]. This technique involves specifying how many elements for each sample need to be considered for each level. This option was done to assure representation in the results obtained. In this way, the modals offered by the firms were considered as layers and the instructors as units directly associated with these layers. A sample was selected from each firm that was proportional to the size of its population. After defining a period of six months (from January to July of 2010) for the collection of the data, the sampling group came up with a total of 109 instructors responsible for different modalities of radical sports. In terms of educational level, it was possible to detect 86 who had university level education (37 with Physical Education diplomas and 49 with diplomas from different courses, such as law, administration, civil forestry engineering, mechatronics, agronomy, tourism, physical therapy, computer science, humanities and psychology). The other 23 instructors had completed high school and were self-employed workers from various segments of the work force. The radical sports instructors were all male whose average age was 31±1.9 years old. Although women do participate in radical sports, they were not included in the sample of this study. The participant’s average teaching experience was 7.2±3.9 years. The standard deviation considered significant was <0.05%.The criteria for inclusion were: instructors belonging to radical sports federations and the signing of a Consent Form indicating they were participating of their own will and that all terms had been clarified[Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE)]. Criteria for the exclusion of instructors were: the candidates did not belong to radical sports federations in the State of Minas or they did not show interest in participating in the investigation. With the goal of establishing a comparative analysis of the aspects related to working as a radical sport instructor, having as a reference the three educational levels of the study’s participants, only the results from the alternatives marked by the participants as being relevant were considered. According to the 3-point Likert type intensity scale[7] employed in the survey, the participant attributed the number (1) as the most important, according to his perception of the question. The statistical analyses were performed using descriptive analysis.

Where: N = population size; n = sample size; d = margin of error; z(k) = desired degree of confidence (using a confidence degree of 95%, which is equal to p = 0.05)Selection of the instructors to define the sample – 147 instructors – was done in a probabilistic manner, using the simplified stratigraphic sampling technique[2]. This technique involves specifying how many elements for each sample need to be considered for each level. This option was done to assure representation in the results obtained. In this way, the modals offered by the firms were considered as layers and the instructors as units directly associated with these layers. A sample was selected from each firm that was proportional to the size of its population. After defining a period of six months (from January to July of 2010) for the collection of the data, the sampling group came up with a total of 109 instructors responsible for different modalities of radical sports. In terms of educational level, it was possible to detect 86 who had university level education (37 with Physical Education diplomas and 49 with diplomas from different courses, such as law, administration, civil forestry engineering, mechatronics, agronomy, tourism, physical therapy, computer science, humanities and psychology). The other 23 instructors had completed high school and were self-employed workers from various segments of the work force. The radical sports instructors were all male whose average age was 31±1.9 years old. Although women do participate in radical sports, they were not included in the sample of this study. The participant’s average teaching experience was 7.2±3.9 years. The standard deviation considered significant was <0.05%.The criteria for inclusion were: instructors belonging to radical sports federations and the signing of a Consent Form indicating they were participating of their own will and that all terms had been clarified[Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE)]. Criteria for the exclusion of instructors were: the candidates did not belong to radical sports federations in the State of Minas or they did not show interest in participating in the investigation. With the goal of establishing a comparative analysis of the aspects related to working as a radical sport instructor, having as a reference the three educational levels of the study’s participants, only the results from the alternatives marked by the participants as being relevant were considered. According to the 3-point Likert type intensity scale[7] employed in the survey, the participant attributed the number (1) as the most important, according to his perception of the question. The statistical analyses were performed using descriptive analysis.3. Results

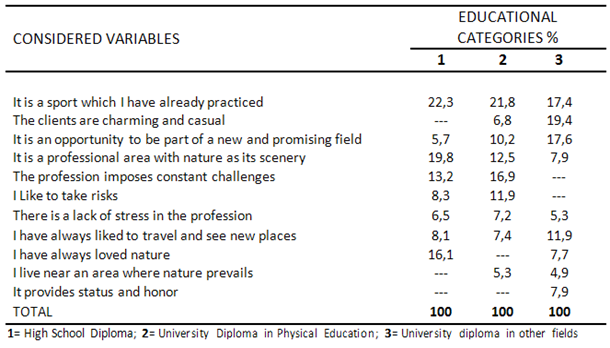

- Table 1 presents the motives which contributed to why the interviewed participants decided to become instructors. Among the principal motives, the most evident were that they already had experience in the chosen sport and that nature served as the scenery, independent of the educational level.

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

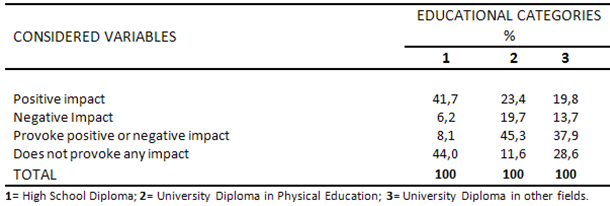

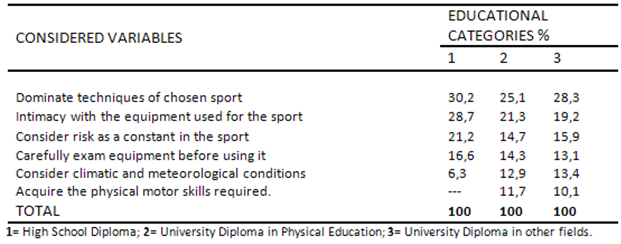

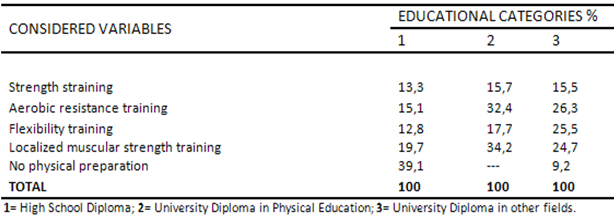

- This type of professional activity does not generally belong to the formal economy and occurs sporadically during certain times of the year, i.e. vacations, holidays, and many times, it is considered a hobby instead of a job, not being recognized as a profession, except when working for recognized sportive institutions. As such, the participants indicated that it is difficult to be employed by a company and to exercise their specialty as a full time job. The fact that the instructors belong to three educational levels demonstrates that in Brazil, there does not exist uniformity in the regulation of the activities for these sports. In other words, until the present date, there is no formal requisite stating that a radical sports instructor has to have a specific diploma (technical or university) in order to teach the chosen sport. Commonly, in terms of a requisite to exercise the profession as an instructor in a given radical sport, the only one is that of a certificate from a technical course, normally of short duration, emitted by confederations and associations of that respective modality. According to Costa, this situation indicates that these instructors have not been officially professionalized[4]. Among the principal motives that contributed to the chosen job of radical sports instructor, there was no significant difference within the educational levels. Most important was there prior experience and refined skills in the given sport. The characteristics that influence those that practice this type of sport are: practiced in nature, sense of risk, and strong emotions. In reference to possible environmental impacts that the practice of radical sports provoke, attention is called to the perception of the instructors with high school education. This is a situation that suggests the need for everyone, especially companies that specialize in offering this type of service, to closely and critically examine the form in which the human actions affect the different natural environments when practicing radical sports for competitive events or leisure. Since radical sport instructors are not officially professionals - a fact that directly focuses on the type of education and minimum skills required for these instructors – the awareness of this profession in relation to environmental preservation becomes relevant and deserves constant attention. If on one side, there is a positive relationship between the interaction of man with nature while practicing this type of sport, on the other side, this process merits attention, since the growing popularity of this activity results in an even greater exploration of the major environmental factors involved in the development of this activity[15, 17]. Usually, when nature is perceived only as scenery for a given sport, environmental impacts provoked by it, becomes irrelevant [11]. Regarding the procedures to be adopted by the student during the course of his chosen sport, taking into consideration his security and physical integrity, the instructors of this study were in general consensus. The most important procedures agreed upon were: dominium of the skills of the chosen sport, intimacy with the equipment and maintenance of the equipment used, awareness of the risks involved and employment of the technology available for the practice of the same. This fact occurs because although there are no specific diplomas for this type of sports, information is constantly being exchange between those participating in a given modality. This includes specialized updating of information through congresses and events, courses, and exchange of experiences among co-workers. As for the adoption or not of complementary forms of physical preparation by the instructors from the three educational levels, those cited were: exercises for strength, resistance, aerobics, flexibility, localized muscle building. It was verified that the instructors graduated in Physical Education adopted or even recommended these exercises to be integrated in their courses. A significant parcel of the instructors with university diplomas in other areas and those with just a high school diploma did not have the custom of implementing physical exercises in their courses. Rarely would the beginning student have the specific physical conditioning required by the chosen sport, i.e. to be able to go for long walks in a hostile land relief, or to be able to survive in adverse temperatures without being able to count on a period of body adaptation, support team, or adequate security equipment to face nature during the practice of the sport. When considering the relevance of the procedures to be adopted for the development and biological, physical, psychological, and motor skill adaptations to be made for the specific sport, it is understood that in radical sports, these procedures acquire greater magnitude and complexity. This is due to the intrinsic characteristics related to the corporal practices involved, such as risks, fear of heights, man-nature contact in different natural environments (water, air or land, including in the latter, deserts, mountains, forests), which in turn demand specific forms of conditioning, skills and capabilities that need to be developed. Among the aspects (aerobics, strength, coordination adaptation, climate, equipment and manipulation, etc.) that deserve attention during the learning process for radical sports, the instructor must pay special attention to the particularities for the chosen sport. Depending on the sport, for example, a set of muscles could be more solicited than others due to the type of muscular contraction (isotonic or isometrical); there is also the influence of altitude and intensity predominant in its practice. Noteworthy is the fact that even though non-competitive perspectives demand less intensity in the performing of these aspects, in nothing does it diminish it relevance in the teaching process. This is because other aspects are also important, such as technique, correct manipulation of equipment specific for the chosen sport, awareness of the natural environment and the procedures required for risk control, not to mention the increased emotions that these sports create. These and other aspects that integrate the physical-motor skill dimension, coupled with the most diverse situations imposed by the outside environment, modifying the perception of the physical-motor skill behavior of the individual, should be considered by the professionals that conduct practices connected with radical sports, so as to orientate the participants during the teaching process. Regarding the State of Minas Gerais, mountain climbing is the most practiced radical sport, due to the State’s geographical relief. It is a sport that demands localized force, especially in the upper members of the body. This requires greater attention on the part of the instructors to develop this area of the body as part of their course. This type of physical-motor skill inclusion in the course applies to other sports modals found int the State. The different modalities of radical sports, practiced in different natural environments, have particularities and independent characteristics. It can happen that the instructors develop, as necessary, determined skills for their performance, which are often intuitive, coming from the practical experience of themselves or others, or from short courses taken in their specific areas. These results confirm the idea that the participants involved in radical sports in Brazil still does not have a professional identity. This fact could directly affect the quality of the services provided in this branch of sports in Brazil.

5. Conclusions

- From the analyses and interpretation of the results obtained in this investigation, and considering the limitations of its methodology, it is possible to affirm that the principal motive that contributed to the adhesion of the individual as an instructor of radical sports to this sector, as well as his permanence in this non-professionalized segment, was his previous experience in practicing it. This situation confirms the uniqueness of this branch of sports in comparison with other traditional sport branches. Together with this, there is nature as the privileged scenery in which these sports are practiced, the risks, the strong emotions and the opportunity to maintain part of the practicing environment: radical sports, whether as a participant, an ex-participant, but mainly in the condition of “instructor”. As for the educational levels of the professionals observed in this study, it was verified that the category in which the instructors presented the least variations regarded actions and procedures that demanded practical experience, such as technique, equipment usage and certain procedures to minimize the risks in the chosen sport. However, due to the limitations in the framework, as well as the education of the instructors in areas so different from that which is involved in the chosen sport, it was perceived that the instructors with high school education and those with diplomas in different fields from that of Physical Education, had difficulty in articulating their knowledge with the actions adopted along the teaching process. For example, they had difficulty in perceiving the importance of the complementary forms adopted for the physical preparations of the students during the course and while practicing the radical sport. Even if the category of radical sports instructors in Brazil is represented by individuals with diversified educational levels and in a majority of cases, in areas other than that of sports, when it comes to teaching, it was verified that these instructors have the necessary knowledge to perform their jobs. Besides their personal training, they obtain addition education through short courses, congresses and an exchange of information between friends and co-workers. Therefore, it is desirable and advisable for the entities, confederations and associations to try to standardize the education and profession of the radical sports instructor, and in doing so, support those who are interested in learning one or more of these sports in Brazil. As a final recommendation, it is important to point out the need for new studies along these lines, involving other aspects connected to radical sports instructors and their practice locations, supplementing or differing from the characteristics presented in this study. Finally, when considering the nature of this instructor’s job, it particularities, the attributions and skills needed by him/her, it is suggested that studies be made that aim at methodological proposal for radical sports practiced in different natural environments, such as land, air and water.

Notes

- 1. This formula employed to calculate the size of the finite population sample was suggested by the Mathematics Department of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML