-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2013; 3(3): 81-91

doi:10.5923/j.sports.20130303.04

What do Coaches Think about Psychological Skills Training in Soccer? A Study with Coaches of Elite Portuguese Teams

Simão de Freitas, Cláudia Dias, António Fonseca

Faculty of Sport, University of Porto, 4200-450, Portugal

Correspondence to: Simão de Freitas, Faculty of Sport, University of Porto, 4200-450, Portugal.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

It is widely recognized that the coach is a key element in the Psychological Skills Training (PST) process. However PST research targeting coaches is very limited, specifically in a soccer context. Therefore, thirteen elite coaches from Portuguese Premier Soccer League were interviewed to explore their thinking about PST process. It was also our aim to examine the coaches’ educational background in sport psychology, as well as their opinions about the role of sport psychologists in soccer. Content analysis of the data revealed that participants acknowledge the importance of PST and the role of the sport psychologist in elite soccer. Nevertheless, participants seem to be unprepared to implement and conduct PST programs. A list of barriers to PST interventions in soccer also emerged from the data. Findings provide several applied implications for practitioners (coaches, directors and sport psychologists). They also serve as a guide to future research and contribute to the development of more specific and effective PST interventions with soccer players and coaches.

Keywords: Psychological Skills Training, Elite Soccer, Sport Psychologists

Cite this paper: Simão de Freitas, Cláudia Dias, António Fonseca, What do Coaches Think about Psychological Skills Training in Soccer? A Study with Coaches of Elite Portuguese Teams, International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 81-91. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20130303.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The main goal of psychological skills training (PST) is to assist sport participants in the development of psychological skills to achieve performance success and personal well-being[1]. PST comprises of a systematic and consistent practice of psychological skills for the purpose of enhancing performance, increasing enjoyment, or achieving greater sport and physical activity self-satisfaction[2]. In order to enhance the psychological preparation of athletes, coaches and teams a systematic PST is required[3]. According to several studies, PST programs have been shown to be an effective strategy for improving athletic performance in a wide variety of sports[4, 5]. In this sense, the study of PST has emerged as one of the main topics in sport psychology.A successful implementation of PST programs is dependent on the head coach because he or she is the manager of the team. Therefore a need exists for an examination of coaches PST knowledge. An in-depth examination of expert coaches’ knowledge would enhance the development and standards of PST programs for coaches and athletes[6]. According to Côté and colleagues[6] it becomes important to examine in more depth the knowledge domain of expert coaches in order to provide useful insights to sport psychologists and new coaches concerning the art of intervening with athletes. It is also important to think not only of the psychological preparation of athletes and coaches in general but also the PST programs for a specific sport. In fact, the different psychological skills, variables and techniques do not exert the same influence in achieving success across the different sports. Thus in attempting to prepare specific PST programs for a certain sport it is crucial to examine the knowledge of the coaches of this sport. In this regard some PST studies were conducted with tennis[7] and netball[8] coaches. Grobbelaar[8] reported that despite the fact that 89,9 % of the netball coaches regard PST as very important, only 46,43% implement PST programmes themselves or made use of sport psychologists. They also found that goal-setting, self-confidence and concentration were the most frequently implemented skills by the coaches who implemented PST programs[8]. Similary, Gould et al.[7], indicated that enjoyment/fun, focus/concentration, self-confidence, emotional control, honesty/integrity, motivation/passion, and positive self-talk/thinking were the most important psychological skills for junior tennis players to develop. These authors[7] stated that while the junior tennis coaches felt that they were fairly knowledgeable in sport psychology their PST knowledge was more influenced by the experience of working with the players rather than by formal courses or books. According to several studies, trial-and-error learning becomes a common procedure among strategies for psychological preparation[7, 9].Although PST is recognized as an invaluable training tool by coaches of various sports[7, 8, 9, 10], it is often excluded from coaching practices because some coaches can be unwilling to implement PST programs and express a negative view point towards using a sport psychologist. Possible explanations for this trend include several stigmas toward PST. A lack of PST knowledge was suggested to be a primary reason why coaches often fail to implement PST programs with their athletes[7, 8, 10]. In this context, a recent study showed that 98,4% of coaches of elite athletes recognized a need for more support in the area of PST[11]. The lack of time for the coaches to teach psychological skills is another frequent barrier to justify the lack of psychological interventions[7]. The lack of finance is also identified as a common barrier for the inclusion of sport psychologists within a team’s staff[12]. Another recurrent barrier that sport psychologists have to face is the stigma that links the sport psychologist to a “shrink”. Martin, Wrisberg, Beitel and Lounsbury[13] stated that the athletes that approach a sport psychologist may fear being stigmatized by the coach or team-mates for having psychological problems. According to Hanrahan, Grove and Lockwood[14] better results could be reached if a sport psychologist was responsible for conducting the PST program. Since the coaches have the power to allow or not allow the interference of external collaborators (e.g., sport psychologists) in their coaching process[15], their attitude regarding to the sport psychologist will interfere with the degree of adherence in PST programs expressed by athletes.Although the aforementioned studies[7, 8] offer valuable insight into the PST with athletes, it should be noted that they do not include the psychological preparation of the coaches. According to Gould, Greenleaf, Guinan and Chung[16], coaches are often required to deal with difficult situations (e.g., selection, tactics, team and athlete performance related issues, decision making) while also ensuring that their own psychological and emotional states remain optimal. For Vealey[1], the purpose of PST is to assist athletes and coaches in the development of psychological skills to achieve performance success and personal well-being. Therefore, a more detailed understanding of this area of research is necessary, because as Thelwell, Weston, Greenlees and Hutchings[17] stated, “the coach can, or should be considered a performance”.Despite being the centre of much public interest and media attention worldwide, little is known about the PST knowledge of expert soccer head coaches. For Potrac, Jones and Cushion[18] it could be suggested that there is a certain degree of “mystique” surrounding the top-level soccer coaches and the means and methods that they utilize in their respective quests to produce successful soccer players and teams. Given the above, a need exists to examine the expert soccer head coach’s knowledge and opinions regarding the PST in soccer. Thus, the present study with coaches of Portuguese elite teams was designed to examine their: a) educational background on sport psychology; b) perspectives on PST with soccer players and teams (including importance of PST, crucial psychological skills, ability to conduct PST programs, and roadblocks to PST), c) perspectives on PST with themselves, and d) receptiveness to work with sport psychologists.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

- The sample of the current study was composed of 13 male professional Portuguese high-level soccer coaches, who ranged in age from 43 to 63. Their experience as soccer coaches ranged from 10 to 29 years. The sample was selected based upon the following criteria: i) have worked, or currently work with “elite-level” athletes’[19], ii) be employed by their respective governing bodies of sport (national squads) or by professional clubs[17] and iii) had a minimum of ten years of soccer coaching experience[20,21].At the time of the interview, all the participants occupied head coach positions in Portuguese Premier League soccer clubs. Furthermore all of the soccer coaches had the highest level of the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) coaching qualification: UEFA Pro License. This research was reviewed and approved by the commission responsible for the ethical issues. All coaches gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

2.2. Instrument

- A semi-structure interview guide was used to conduct the interviews. The interview guide was developed based on the interview protocol of Taylor and Schneider[22] and was organized into five sections. Section 1 contained demographic information and other introductory comments. In this section participants were informed about the purpose of the study and the structure of the interview. Several brief key definitions (e.g. “sport psychology”, “psychological skills”, “psychological techniques” and “psychological skills training”) were clarified for the participants in order to establish rapport and to orient them to the interview process. Section 2 analysed the coaches’ educational background on sport psychology (e.g. Did you have formal education in Sport Psychology? Where did your sport psychology knowledge come from?). Section 3 examined the importance assigned to PST in soccer (e.g. What is your opinion about the importance of Psychological skills training in soccer? Which psychological skills do you consider crucial for soccer players and the team’s performance? ). Section 4 explored the coaches’ perceptions regarding the sport psychologist services in soccer (e.g. What is your opinion about the importance of sport psychologists in soccer? Are you receptive to work with these experts?).The last section of the interview guide provided the opportunity for any final comments and summary questions from both the interviewer and interviewee.

2.3. Procedures

- All interviews were conducted face-to-face by the first author of the present investigation. The interviewer had previous experience as assistant soccer coach in the Portuguese Premier League and was therefore familiar with the history, experiences and terminology used by the participants. For Lincoln and Guba[23], this was one method of ensuring the trustworthiness of the data collection. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and was conducted face to face in an environment comfortable for the participants. Nine of the 13 interviews took place in the coaches’ office before or after a training session. Of the remaining interviews, three were conducted in the coach’s home, and one in a hotel room.

2.4. Data Analysis

- Interviews were analyzed in a process of inductive-deductive content analysis[24], which consisted of several steps. First, interviews were transcribed, read and reread by the first author in order to become completely familiar with the content. Second, raw data themes i.e. quotes or paraphrasing to represent a meaningful point or thought, were identified and coded. Different levels of coding were developed to refine categories until saturation of data was reached. First-order subthemes, second- order subthemes and general dimensions were established according to a progressive level of higher abstraction. Next, in order to establish trustworthiness, all findings were presented and discussed with another author to serve as a “devil advocate”[25]. After discussion, different suggestions were presented, changes were made as appropriate and a final consensus was reached. Finally, the first author checked all the findings again in depth to provide a validity check.

3. Results

- The inductive-deductive analysis exposed four general dimensions that emerged from 66 raw data themes identified by the participants. The dimensions were abstracted from 14 second-order subthemes and these from 25 first-order subthemes represented in figures 1-4.

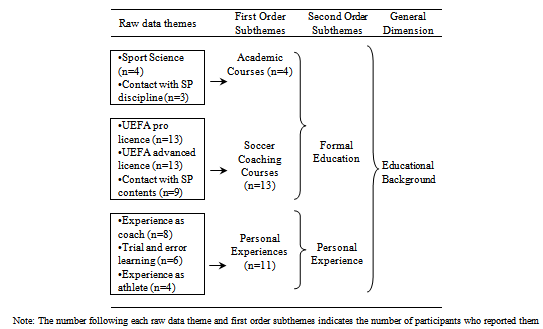

3.1. Educational Background in Sport Psychology

- This dimension comprised of the coaches’ education in sport psychology. Eight raw data themes were included in this dimension and two second-order subthemes were used to define it (Figure 1).The formal education of the participants in Sport Psychology was based on academic courses (n=4) and coaching training courses (n=13). Four participants indicated having contact with Sport Psychology discipline in their sports science academic courses. They also referred to additional contact with sport psychology discipline due to their participation in soccer coaching training courses. However, others coaches mentioned that their only formal psychological education was the hours of sport psychology within their soccer coaching courses. For example, one participant stated:I haven’t got any academic education. The only study I’ve had has been my soccer course at level III and IV. A discipline with sports psychology content exists within these courses and this is the only formal education I’ve received.

| Figure 1. Soccer coaches’ educational background in Sport Psychology (SP) |

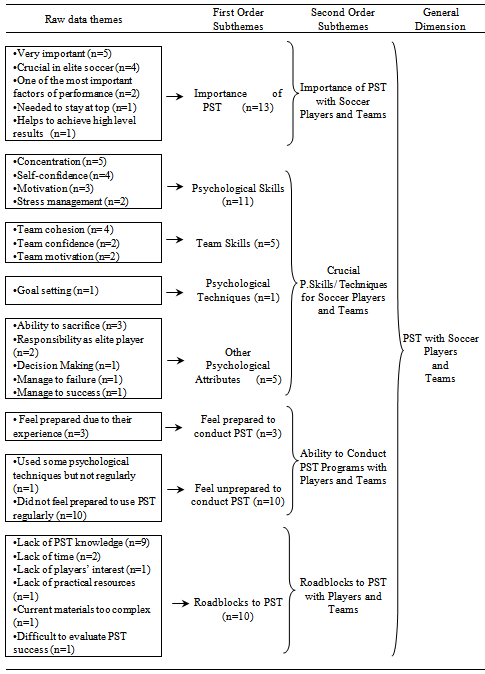

3.2. PST with Soccer Players and Teams

- The second dimension is related to the coaches’ perspective about the PST with soccer players and teams. This dimension included 27 raw data subthemes that were grouped into four second order subthemes: importance of PST, crucial psychological skills, ability to conduct PST and roadblocks to PST with soccer players and teams (Figure 2).

| Figure 2. Soccer coaches’ perspectives about PST on soccer players and teams |

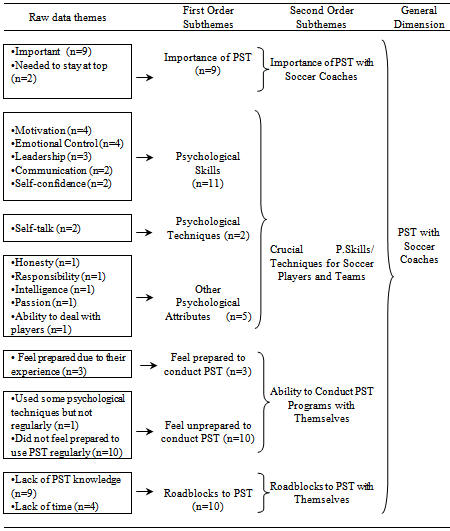

3.3. PST with Soccer Coaches

- The third general dimension pointed out the coaches’ perspectives about the PST with themselves. Eighteen raw data themes comprised this dimension and four second-order subthemes were used to define it (Figure 3).The first second-order subtheme highlighted the importance of the PST with coaches. Nine of the participants recognized the important role of their own PST. Additionally two coaches also mentioned that the coaches PST was needed to stay at the top (n=2).The second second-order theme, crucial psychological skills for soccer coaches, illustrated the importance given by eleven participants to psychological skills such as motivation, emotional control and leadership. In this second-order subtheme, some participants also mentioned a range of other psychological attributes (n=5) and a specific psychological technique (n=2) that they consider important for their own performance.With respect to the third second-order subtheme, ability to implement PST programs with themselves, the majority of the sample (n=10) reported not feeling prepared for this.The last second-order subtheme, roadblocks to the coaches PST, illustrated two roadblocks identified by the participants: lack of PST knowledge (n=9) and the lack of time (n=4).In my opinion the biggest obstacle that a coach faces regarding his own psychological preparation is the lack of knowledge as well as the lack of time to implement the PST programs.

| Figure 3. Soccer coaches’ perspectives about PST on soccer coaches |

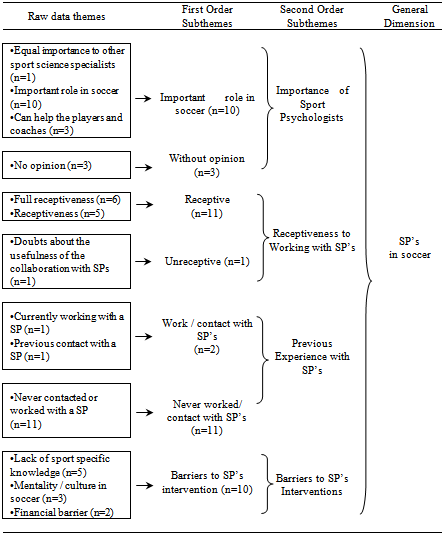

3.4. Sport Psychologists Service in Soccer

- The last general dimension is related to a group of issues regarding the coach’s opinions about the role of the sport psychologist in soccer.Thirteen raw data themes were included in this dimension that was grouped directly into four second-order subthemes: importance of sport psychologists, receptiveness to working with sport psychologists, previous experience with sport psychologists and barriers to sport psychologist’s interventions.Ten of the participants were unanimous in stating the important role of sport psychologists in soccer. For instance, one participant said: It is evident that the sport psychologist could be important in soccer. Soccer involves many branches of science and these exist in conjunction with several specialists that include the sport psychologist. I believe that these experts can and should be in elite soccer.Regarding the coaches receptiveness to work with sport psychologists in soccer, eleven participants showed receptiveness to this type of collaboration.If I feel that the collaboration with the sport psychologist is going to bring benefits for the players, and if the administrators don’t object to hiring these experts, I would be receptive to working with them.In contrast one of the coaches expressed some doubts about the usefulness of the collaboration with these experts in soccer. The following quote illustrates this opinion: I think an experienced coach is perfectly capable of managing their players and teams psychologically. I could say to you that I am receptive to working with a psychologist but I wouldn’t be honest with you. At the moment, for lots of reasons, I can’t see myself working with an expert in this area.When the participants were asked about their previous experience with sport psychologists, more than half of the sample stated that they have never worked with these experts. On the other hand, one of the coaches mentioned currently working with a sport psychologist. However this coach reported that the sport psychologist had no direct contact with the players and team, as is well illustrated in the following expression: I worked with a sport psychologist for a couple of years, but he was never hired by the club. The sport psychologist was a personal service and consequently he had no direct contact with the team or with the players. He was a consultant that helped me to coordinate the psychological preparation of my players and teams as well as my own preparation.Also in this context, the same coach expressed one idea that can be linked with some of the barriers to a sport psychology intervention.I know that this isn’t an ideal type of intervention but as you know sometimes we can’t hire all of the assistant coaches that we want for the club. We are limited to hiring one or two assistant coaches because the club already has other internal assistant coaches. With respect to the aforementioned (barriers to sport psychologist intervention in soccer) the participants listed other possible reasons, such as lack of sport specific knowledge (n=5), mentality / culture in soccer (n=3) and lack of time (n=1) and finances (n=1).

| Figure 4. Soccer coaches’ perspectives on sport psychologists (SPs) |

4. Discussion

- The current study was designed to examine the thoughts of Portuguese soccer coaches regarding the PST process. Additionally, we intend to explore the soccer coaches’ educational background in sport psychology and their opinions about the role of sport psychologists in soccer.With respect to the formal education in sport psychology, only four of the coaches were exposed to sport psychology in their academic courses. On the other hand, all of the coaches reported had formal contact with sport psychology contents during their coaching training courses (UEFA licence, promoted by the Portuguese Federation of soccer). Therefore it should be expected that this group of coaches would be well educated in the field of sport psychology. However, doubts can be raised regarding soccer coaches psychological education in these courses. In fact, these soccer coaching courses do not seem to give the necessary importance to the discipline of sport psychology. For example, according to the regulation of the UEFA Pro licence[26] only 15 hours were used in the discipline of the behaviour of science (that includes sport psychology contents). In contrast, 56 hours were used in the discipline of training methodology and 50 hours for the disciplines of technical/tactical and physical skills. In line with this, Fonseca[27] stated that soccer coaching courses in Portugal give less importance to psychological factors since the amount of hours designated to sport psychology within these courses, is significantly less than others modules.Therefore it is not surprising that more than half of the sample considered that their sport psychology knowledge came from personal and practical experiences, especially coaching experience. In the same way, Gould and colleagues[7] found that tennis coaches’ knowledge of sport psychology was more influenced by the experience of working with players rather than by formal courses. Gould et al.[7] and Sullivan and Hodge[9] stated that trial and error learning becomes a common procedure among strategies for psychological preparation. In this regard, Grobbelaar[8] reported that although the majority of netball coaches made use of trial and error methods, they perceived these methods rather ineffective.Given the above, it seems important that the Portuguese Federation of Soccer (responsible for the coaching soccer courses) should pay more attention for the good practice examples of other countries. For example, the Football Association of England has recently introduced its ‘Psychology for Football’ strategy to develop better players and coaches in England[28]. A range of courses aimed at coaches, players and support staff has been developed to educate these groups in the concepts of sport psychology[28]. Similarly, Morris[15] indicated that coaching organizations in several countries (e.g. UK, USA and Australia) have established sport psychology modules in their different levels of coaching education programmes.The second research question sought to determine the importance assigned by the coaches to the PST in soccer. All of the coaches revealed a positive and favourable perspective about the importance of PST, which are in agreement with the PST literature[29, 30, 31, 32]. This is an encouraging finding and reflects the high status that PST in soccer has among these elite national coaches.When evaluating the crucial psychological skills for soccer players and teams, one could argue that concentration, self-confidence and team cohesion were the skills most frequently mentioned by the coaches. These findings are not surprising, because the importance of these three psychological skills is often addressed in the psychological skill literature as well as in the soccer media. Several studies show the crucial role that self-confidence and concentration play in athlete’s performance[33, 34, 35, 36]. Relative to group cohesion, investigators showed this skill as being effective for improving relationship patterns among all elements of the group, pursuing the established goals that lead to team success[37, 38, 39]. It is also encouraging that the three psychological skills most mentioned by our coaches are often discussed in the psychological skills literature. However, a review in soccer PST literature shows that few or no studies investigated the concrete strategies that coaches used to enhance the concentration, self-confidence and cohesion of their players and teams. Given the above, sport psychology researches should consider exploring these issues.With respect to the psychological skills considered most relevant for the soccer coaches, the results of our analysis revealed that motivation and emotional self-control were the skills most frequently mentioned by the sample. The professional instability and the high psychological pressure that the soccer coach is constantly subjected to, may explain this finding.For Vealey[1], it seems important to identify key psychological skills that are related to performance success and personal well-being to guide the development of psychological skills interventions. In this sense the set of psychological skills identified in the present study should serve as a relevant indicator for the development of more specific and effective psychological interventions in soccer. However, for this support to be most effective and specific as possible, future research should identify the key psychological skills according to the players and coaches characteristics (e.g. gender, age), as well as the players position in the field (e.g. goalkeepers, defenders, midfielders and attackers). Although participants were aware of the importance of PST on soccer players and coaches performance and elected a set of crucial psychological skills (that are consistent with the sport psychological literature), they have given less relevance to the psychological techniques. According to the above it is not surprising that the majority of the coaches admitted to feeling unprepared to conduct and apply the PST process. This finding is in agreement with the PST literature that showed that coaches have difficulties in understanding deep psychological techniques[40].In this context it should be noted that even the coaches who considered themselves to be relatively well prepared to conduct psychological training, mentioned that their intervention was based only on their experience as coach and previously as players. Thus, it seems evident that these coaches do not have the correct understanding about the PST process. According to Fonseca[41] “one thing is the coach had general knowledge about sport psychology that allowed them to perform better and positively influence their players and teams psychologically. Another thing is the coach was prepared to use the different psychological techniques and help their players to develop strategies in this sense”.Results of the current study also revealed information about the roadblocks to the development of PST in soccer. In particular, the biggest roadblocks identified by this sample of coaches included the lack of PST knowledge. Malete and Feltz[42] stated that a lack of knowledge on PST was a barrier to coaching effectiveness. Similarly, Vealey[43] indicated that coaches usually neglected the PST because they lacked the knowledge to train these skills. To help overcome these obstacles, coaches may benefit from collaboration with sport psychologists. Therefore, the agreement of the majority of the sample about the importance of sport psychologists and the receptiveness to work with these experts was not surprising. Similarly, Sullivan and Hodge[9] found that 97% of the coaches’ surveyed in their study indicated interest in working with a sport psychologist. In this context, Anderson [44] described a twofold perspective of collaboration between coach and sport psychologists. One form of coach consultation is focused on the coaching practices in order to support the psychological preparation of his/her athletes. Another situation occurs when coaches seek consultation not for their athletes but for their own personal and professional needs (e.g. anxiety). This study did not attempt to evaluate the type of soccer coach/sport psychologists’ collaboration. Future research could explore this topic. According to the previous finding, we would expect a high level of collaboration between elite Portuguese soccer head coaches and sport psychologists. However, when the coaches were asked about their previous experience with sport psychologists, only one coach reported that he had the support of a sport psychologist. In this respect, Fonseca[41] referred that the existence of a sport psychologist in professional, Portuguese soccer teams is an exception not the rule.Therefore we are faced with a paradox which is important to understand. If the soccer coaches are receptive to working with sport psychologists, why are they not hired by the clubs?The coaches of the sample mentioned a list of barriers that limited the sport psychologist intervention in soccer. A lack of sport-specific knowledge on the part of the sport psychologist was cited as the most significant barrier. Gould, Murphy, Tammen and May[45], found that Olympic coaches suggested that sport psychologists should increase their sport-specific knowledge and, consequently, the specific psychological skills strategies. For this purpose, one of the most recognized soccer coaches in the world, Fábio Capello [cit. in 41], stated that “is crucial that a sport psychologist working in elite soccer completely understands soccer, is involved in this sport, and is prepared to understand the problems related to this type of activity”.Other barriers that are well described in literature such as lack of time and lack of finances[28], also emerged in the present study. However, in our opinion these perspectives are quite questionable. In fact, with the huge budgets that currently exist in professional soccer the inclusion of a sport psychologist will not endanger the budget of the club.Therefore, the question of background seems to be connected with the idea that some of the coaches believe that sport psychologists, have a small contribution to the performance of soccer players and coaches. At this level, it should be noted that three of the participants stated that the general cultural mentality in Portuguese soccer was a barrier to sport psychologists. For Pain and Harwood[28], despite the continued success of sport psychology across the globe, negative connotations of the field still exist, particularly within sports such as soccer, that have tended to resist change. An educational program on the psychological concepts, targeting coaches and directors may help to remove negative connotations of sport psychologists and consequently change the culture of soccer. At this level, soccer coaching courses promoted by the Portuguese Football Federation could play an important role because for the majority of the participants these courses are the only source of formal education in sport psychology. It should be noted, however, that it is fundamental to reformulate these courses, increasing the number of hours devoted to sport psychology.If the Portuguese Federation of Soccer delivers the appropriate Psychology education to the soccer coaches and administrators and if sport psychologists can enhance their soccer knowledge, the barriers could be overcome and the opportunities for the collaboration between coaches and sport psychologists will increase.

5. Conclusions

- The findings of our study may be interpreted as being supportive of the importance of the PST process in professional soccer. However, although the participants acknowledge the importance of PST and the role of sport psychologists, they did not feel able to design and apply PST programs with players, as well as, with themselves. Therefore the need to educate soccer coaches providing more applicable, concrete and practical PST information is necessary. While the present study provides important implications relative to PST process in the context of Portuguese professional soccer, it should be noted that the findings are related to the unique characteristic of our sample and transferability of the results is limited. Therefore, methodological limitations must be considered when making interpretations about the type of sport (i.e., only one sport-soccer) and gender (i.e., only one gender – male) of the sample. However, since the purpose of the current study was not to make comparisons between groups, these issues did not affect the trustworthiness of the research. On the other hand the sport represented (soccer – one of the most important sports worldwide) and the high quality of the sample (i.e. coaches of elite Portuguese Teams) can be considered a strength of this research. Finally it should be noted that the current study reflected the thoughts and not necessarily the actual behavior of the coaches. Therefore, further research is needed to assess the actual PST behavior of coaches.In summary, the current study can serve as a guide to future PST soccer research and, from a practical perspective, may serve to highlight several recommendations for making PST more effective in the context of Portuguese soccer.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML