-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

p-ISSN: 2169-8759 e-ISSN: 2169-8791

2012; 2(5): 51-60

doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20120205.02

Thriving in the Challenge of Geographical Dislocation: A Case Study of Elite Australian Footballers

Martin Harris1, Marion Myhill2, Judi Walker3

1Department of Rural Health, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia.

2Department of Education, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia

3Department of Rural Health, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

Correspondence to: Martin Harris, Department of Rural Health, University of Tasmania, Launceston, Australia..

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Young adult athletes are often required to relocate as part of their career progression. The transition between their 'old' and 'new' lives can have a positive or negative effect on their future career. The purpose of this study was to identify the processes and characteristics of thriving in periods of geographical dislocation; particularly the move away from the ‘familiar’ to the ‘unfamiliar’. A partially mixed, sequential design was employed, initially to identify the individualities of a group of 24 elite athletes. Despite their homogeneity on a range of instruments, the outcome variations were not adequately explained. Subsequently, the particular characteristics and processes that contribute to thriving were examined through a sequence of semi-structured interviews, and analysis. The responses that led to positive outcomes (thriving), in comparison to less positive (surviving), or even negative (languishing) outcomes are identified and discussed. The findings inform the need for a more nuanced and detailed cyclic, rather than linear, approach to the transition and any associated intervention strategies. Further research is needed to examine this new approach to managing transitions with different groups of participants and in other dislocating and transitional contexts.

Keywords: Thriving, Transition, Positive Growth, Learning, Dislocation

Cite this paper: Martin Harris, Marion Myhill, Judi Walker, "Thriving in the Challenge of Geographical Dislocation: A Case Study of Elite Australian Footballers", International Journal of Sports Science, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 51-60. doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20120205.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. The Challenge of a Geographically Dislocating Transition

- The purpose of this study was to identify the processes and characteristics of thriving in periods of geographical dislocation. The physical relocation of an individual involving the loss of familiar support systems, (i.e. geographical dislocation), constitutes a significant challenge with potential threats to self-esteem[1], destabilising ambiguity of role[2], stress in regard to uncertainty[3, 4], and challenges to autonomy through a reduced sense of control[5].The individual experience of geographically dislocating transitions has been more difficult to describe because of the personal meaning attached to change[6]. Although geographical dislocation is usually considered a time-limited event, there remains an opportunity for negative long-term consequences as well. If the challenge is poorly resolved there is more likelihood of chaos and disruption of routines, greater uncertainty, and a longer period of adjustment. Nicholson’s findings from workplace studies show that high levels of role novelty and role ambiguity also increase uncertainty[7, 8], and the potential for longer term difficulties is high. The significance of this study is to position the qualities of thriving within Nicholson’s framework to create a new model that informs the opportunities for early intervention and support. Regardless of whether the geographical dislocation is desired or undesired, there is often confusion and pre-occupation with the characteristics of the new environment and the loss of the old one[9-11]. These contextual stresses are more particularly felt when there are changes in social networks [12, 13], and there is a perceived loss of environmental mastery[14, 15].The consistent thread of this research is that transition is a move from the familiar to the unfamiliar, with accompanying disruption of routines and psychological uncertainty.

1.2. The Thriving Response to a Challenge

- Engaging a challenge is considered as transformative[16], with three indicated outcomes (a) languishing, affected by the stressor and unable to make progress; (b) surviving, with a return to a baseline of strategies; or (c) thriving, where growth and learning is evident. Thriving is defined as a positive response to a challenge[17] where gain occurs, rather than the minimisation of loss[16]. In contrast to resilience, thriving is not a response to extreme circumstances but a response to the more difficult but everyday challenges of life: a response to challenging circumstances rather than adversity and with a focus on learning and growth. Thriving is a reaction to circumstances that are sufficiently destabilising to require the individual to re-examine the self and is the means through which the individual is motivated to function at a higher level[18].While studies[e.g. 16, 17, 18] have examined the notion of thriving as an opportunity for learning and growth, none have examined this potential within a cyclic transition, where the stages well resolved further enable the individual.

2. Method

- This study involved a comparatively homogenous group of 24 elite Australian football players (young men, aged between 18 and 25) who were required to relocate as part of their contract with the football club. Drafted to their respective clubs, they were drawn from anelite pool of aspiring, domestic athletes in 2006/7. The selection criteria included those young men for whom interstate relocation was a requirement of their contract.Following ethics approval, the strategic selection of young men was designed to provide a cohort of comparable individuals, experiencing a similar transition, rather than to imply characteristics specific to the gender or age-group.All participants provided informed consent.

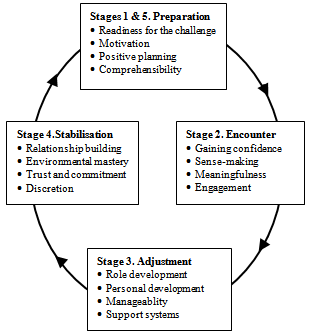

| Figure 1. The thriving transition cycle, showing attributed concepts |

3. Results

3.1. Readiness for the Challenge

- With varying degrees of success, the participants were able to consider their initial reactions and find ways of shaping a useful framework for negotiating the geographically dislocating transition process. Some participants were able to see the transition as purposeful and avoided the distracting preoccupation with the characteristics of the new environment and the loss of the old. Those who thrived strategized the shift from the familiar to the unfamiliar by a purposeful search for patterns: “… it was good to have other guys around you that were going through the same thing … and you could always sit with them … and they would be having the same thoughts as you … or you could ask them something and not feel like a[fool]” (Participant 01).For thrivers the dislocating transition was a process of reorientation[10], rather than an event to be surmounted, and they had an awareness of the changes taking place and how they could be engaged. This underscored the importance of feeling situated, and having a level of awareness to face the challenge in a meaningful way[21]. Those identified as surviving were broadly aware of the challenge ahead but found difficulty in defining it in any meaningful way. This was evident in the difference between their expectations and the experience[22], where they struggled to visualise a pathway for their journey: “I think it’s hard to put all your energy into that. I think at this time of year it’s too hard, like, our training schedules … it’s just out of control and it’s just getting worse” (Participant 24).Those languishing were unaware of the tasks that confronted them, and the strategies that might be usefully devised or applied, and were clearly distinguished by their responses:“… but I was actually having second thoughts about whether I wanted to live that (life) … and I wasn’t really committed in what I was doing anymore” (Participant 11).

3.2. Motivation

- The participants’ willingness to engage in the dislocating transition tended to be either tentative or confident. The data indicated that the participants’ motivation was more closely related to their preparations for the transition and the application of their resources to accommodate the psychological need to plan ahead, than their enthusiasm for the challenging tasks. The participants identified as thriving demonstrated strong associations with the positive aspects of this concept: they were confident, optimistic and had proactive coping strategies. This was particularly evident in their ability to understand and respond to feedback[23], and their capacity to develop confidence in the transition pathways: “I think I always had an underlying confidence that I could do quite well … you get a bit of feedback that you’re doing okay, it gives you a lot of confidence” (Participant 05).Those surviving were less confident and inclined to be overwhelmed by the challenge to move from the known to the unknown. Survivors found it difficult to prioritise tasks, and were motivated by the excitement of the occasion rather than an awareness of the strategic opportunity. Survivors were less likely to seek feedback, and the influence of feedback was confusing and sometimes counterproductive. Those languishing appeared bewildered by the experience and found little guidance in the assistance offered to them. They were excited by the prospect of the transition, but unable to motivate themselves in a way that was productive:“[The coach] didn’t really give you that much confidence, like, you didn’t really talk to anyone … so, I didn’t really know where I was going” (Participant 18).

3.3. Positive Planning

- The ability to negotiate and plan personal pathways requires control and strategies free from the past. The participants’ challenge was to leave a familiar environment and embrace a new, unfamiliar environment. This concept explored the uncertainty of relocation[24] and the ways in which uncertainty was reduced. Attachment to place[e.g. 25, 26], and consequent difficulty in planning for the future, became part of the discriminating criteria. Similarly homesickness[e.g. 27, 28] was examined in relation to the participants’ planning focus. Participants identified as thriving were able to demonstrate more particular associations with the positive aspects of this concept, such as assuredness, positive detachment, and confident planning: “Well it’s still a cut-throat business and you do what you can to help the team, but you’ve got to make sure that your success is ensured as well” (Participant 01).Those surviving were more guarded about the experience and felt their way through the process. Their expectations were often coloured by competing observations within the new environment and they struggled with conflicting interests. Those languishing were confused and struggled with the new responsibilities; they were consumed by fears of failing, rather than seeking support from others:“… just watch other people … I did … I watched people pretty closely and noticed how they went about things and tried to copy” (Participant 04).

3.4. Comprehensibility

- The participants’ grasp of concerns in the transition process provided a structured understanding of the imminent challenge. This awareness was a defining characteristic of a successful transition and required a timeframe that was enabling. To thrive in this transition required participants to understand what the journey might entail[29] and the components of the challenging circumstance. This included perceptions of control[30], purpose[15, 31], and confidence in their ability to master the new environment[32]:“I think I know my part in the team and … I think I know what is required and I think … I know that I can produce it so … I think that gives me a lot of confidence” (Participant 05).By contrast, the survivors were less clear about the tasks ahead and were inclined to follow the example of others rather than to understand the personal nature of the journey. The consequence was often a misfit between expectations and reality[22] and general confusion about how they should engage with the transition tasks[21]: “… it’s pretty self-explanatory; really, just follow in the older player's footsteps, whatever they do, you do” (Participant 20).Those at risk of languishing had little understanding of what was required of them and were only able to engage in the transition process in the most mechanical of ways. Those languishing struggled with the process from the outset, and information designed to be facilitating and supportive was confusing and bewildering:“Oh, you’re obviously a bit unsure, like you’re … sort of wait[ing] for someone else, to follow their lead” (Participant 04).

3.5. Gaining Confidence

- It was important to measure the participants’ ability to learn lessons from the experience of dislocation[33-35] and better understand the mismatch between anticipated pathways and their experience. Thrivers were confident and resourceful, and continued to apply their new-found skills to the challenge: “I wasn’t doing it by myself and I remember thinking we’re all in this together” (Participant 01) Survivors were less confident about the transition and were still searching for direction in regard to the details of what was required of them. Their learning was haphazard and it was difficult for them to apply information and resources to the tasks they faced. Those languishing found it difficult to describe a frame of reference for their transitional journey and were locked into strategies that did not serve them well and as a consequence, their opportunities for productive learning were very limited:“You know, you’ll see someone’s looking at you and you go ‘is he not working hard?’ or ‘what am I doing here?’… it puts thoughts in your head sometimes” (Participant 02).

3.6. Sense Making

- The likelihood of thriving is heightened when it is possible to make sense of the experience of the dislocating challenge. While all participants were keenly experiencing the new environment, only some were able to make sense of the transitions and associated challenges. Responses ranged from being bewildered and confused, to a watchful and adaptive recovery. Those thriving were able to learn from observations and make positive changes that gave them clarity of purpose[32]: “[You] help others as much as you can, but there’s a certain point where you’ve got to say a couple of tricks are my tricks and you can’t have them” (Participant 01).Those surviving struggled for clarity of direction, although they were beginning to understand the range of experiences involved in the transition. They were aware of the challenges and associated tasks[22], but had difficulty in applying the knowledge[24, 30]. Further, they were inclined to see the transition and the challenge as a single entity, rather than a suite of demands: “You’ve got to change your whole way of thinking to the team and do the team thing really” (Participant 20).Those languishing were confused and struggled for direction, they were pre-occupied with the characteristics of the new environment and the loss of the old one[24, 30, 36, 37]. They grasped at any opportunity and mimicked others to try and make sense of their experiences. By not seeing or accepting that the reality had changed they no longer understood what was happening to them[38, p.40]: “I didn’t know what to expect … I guess I wasn’t working hard enough, but I thought I was working hard enough” (Participant 02).

3.7. Meaningfulness

- Thrivers had the ability to identify the components of the challenge as meaningful and worthy of engagement, and to understand why they were committing valuable resources to the components of the challenge[29, 39]. Meaningful engagement[21] allowed the participants to discriminate between the mundane tasks and those that enabled them in the transition process[19]. This focussed orientation allowed thrivers to perform and learn[40], and allowed them to calculate the worthiness of their engagement[41]:“I know a lot more about myself … I’m moving away from having potential and more towards having to produce” (Participant 03).Survivors were less able to identify the reasons for the engagement other than it was an undefined expectation of the organisation, but one they were keen to fulfil. They were inclined towards a ‘goal-prove’ orientation[40], had difficulty in finding meaning in the efforts, and attributed the dedication of resources as an external requirement. Those that languished were inclined to a ‘goal-avoid’ orientation[40] and found it difficult to attach meaning to any aspect of the transition. They were absorbed by the risk of error and were disabled by the process. In the most part they regarded the transition as a series of important, albeit meaningless, activities:“It didn’t make sense to me in the first year … I couldn’t handle it ... it was just a whole shock” (Participant 22).

3.8. Engagement

- Thrivers were significantly involved in the adjustment tasks[42]. They demonstrated engagement by information-seeking and executing thoughtful change throughout the learning process[21] that the transition provided: “I reckon it was sort of good in a way that you moved to here straight away so that you … get all your loose ends sort of tied up … and settled in after that” (Participant 09).The survivors were more likely to be overwhelmed by the transition and wrestled with the competing emotions of leaving the past behind and engaging with the new environment[28]. The survivor’s enthusiasm for the move was tempered by their lack of real engagement, and they found it difficult to discriminate among the engagement priorities: “I can totally understand it ... people come and go and their focus is that whole circle, and when you’re in there you’re the best of mates but when you’re out of it, it’s almost like you’re forgotten” (Participant 07).Those that languished struggled to break with the old environment and engage with the new. They were overwhelmed by the apparent volume of tasks and found their resources stretched to the full. They kept their old life on- hold and made tentative and weak overtures to engage with others in the new environment:“I think it can be overwhelming sometimes, people telling you different things and you don't know who to listen to, or which parts of it to take for yourself” (Participant 22).

3.9. Role Development.

- This concept is concerned with the balance between the participants’ altruism and their competitiveness in the context of the evolving role-fit relationship. Thrivers evolved strategies to develop autonomy in, and some degree of mastery of, the new environment and were able to adapt to the demands of the new environment and the dimensions of the transition[19, 43]. Thrivers also felt connected to the new environment:“I’d been up here for ... three months. I thought I was getting in the groove of it … you’ve got to organise yourself differently” (Participant 21).The survivors had less insight into their opportunity to select strategies and were more likely to conform to group expectations irrespective of their suitability: “As an 18-year-old, you’re trying to fit in with the boys and you’re trying to immerse yourself in the whole environment and it took me a year or so ... to find where I wanted to be in the whole environment” (Participant 07).Those that languished were confused and tried to please others by conforming and applying themselves to strategies they had observed. They mimicked others and resigned themselves to the outcomes that flowed from their efforts, rather than reflecting on the transition, their emerging role, and what had worked for them:“I’d been taken out of one life and thrown into a life that I didn’t know existed and … had no clear warning what it would be like, what to expect, what social life” (Participant 11).

3.10. Manageability

- The thrivers were able to accommodate the pressure of the dislocation with a balanced approach and a sense of the manageability of the requisite tasks:“When you first come down it’s so exciting and it’s so new … and you don’t fully understand how long you could be away … you really understand how important the family side of it is when you’ve been away … but having that understanding from the club point of view is really helpful” (Participant 05).The survivors were more likely to see the transition as a whole rather than the component parts and were less able to access the resources or strategies to assist them. They were aware of the challenging circumstances, but unable to discriminate among the tasks. Survivors were still linked to their old ways of coping[44, 45] and had awareness without direction: “I think when I came here, there were no real expectations of me, but then (after time), there were and I think I struggled a bit with that” (Participant 08).Those that languished struggled to find the manageable aspects of the transition and were often overwhelmed by the apparent magnitude of the experience. They were confused and inclined to embark on strategies that were instinctive rather than connected to a frame of reference:“I’ve barely reached out, been a part of normal life. You know it gets really, really hard; you don’t get the chance to get outside the bubble” (Participant 24)

3.11. Support Systems

- The nature and perceived availability of the participants’ support systems during the dislocating transition is a key component of success[35]. The thrivers were able to mobilise the individual and social resources to facilitate positive physical, emotional and social outcomes. Thriving participants could identify and access support systems (including their immediate friends, family and supporters) and new systems in the form of structures and routines. The more subtle aspects included the participants’ perceptions of these being available, or of value to their particular circumstance. The thrivers were able to identify and use support systems from a variety of sources and select those of most value: “I was lucky to have the[support] I had … and I reckon it would’ve been a lot harder if I’d been living somewhere by myself … Some of the players haven’t been so lucky and I know it’s been harder for them” (Participant 03).The survivors were able to identify the support systems around them, but found it more difficult to access them in a timely fashion: “I reckon it was just hard to get your head around ... actually being here and being amongst them and doing the same thing as them …[it] takes you a while to sort of[say] I’m actually a part of this now” (Participant 09).Those who languished had difficulty identifying sources of support and were troubled investing trust in them. They were consumed by the challenge and clung to dislocated support systems in an effort to survive:“If I did have any spare time it was quite lonely in a foreign place … but they just sort of left us to our own devices, and you know, there probably wasn’t much more they could do I guess, but you do tend to find yourself getting a bit lonely” (Participant 09).

3.12. Personal Development

- The ability to process the experience of the dislocation in a meaningful way and to learn from the experience was important. The participants who thrived were able to identify development pathways and the learning experiences that characterised the process, for example seeking feedback to allay concerns[40]. They were comfortable with the demands made of them and were able to derive substantial satisfaction from the progress they made: “… once you get up here you realise that everyone is on a pretty level playing field” (Participant 21).The survivors were able to identify aspects of the development process, but did not have a sense of satisfaction as issues remained unresolved. They were prepared to work hard towards their goals, but understood the experience less: “I’ve come this far, it would be a shame to walk away … I knew the pathway was, you know, not always clear-cut” (Participant 14).Those who languished were more likely to feel a sense of personal stagnation as the processes were not well understood. They were unable to identify particulars from general praise, and were disabled by criticism:“If you're down, put the poker face on they … you know, no-one knows you're down, sometimes I'm down, but then I try and put the poker face on” (Participant 15).

3.13. Relationship Building

- By definition, the participants had left many of their friends and family behind and were obliged to look for alternate relationships or remain isolated. In that regard, the participants’ shifting attachments were examined[46], as were the strategies employed to form new friendships and embrace the new environment. The dislocation concerns, including missing family and friends and adjusting to independent living[24] weighed heavily on some participants and limited their ability to thrive in the new environment. The importance of particular relationships, such as those with medical staff for recuperating participants[47] and coaching staff[e.g. 48, 49], was evident in this study. The participants identified as thriving demonstrated genuine warmth towards others: “… it’s probably the best thing about playing a team sport and … achieving things together so … you get to know the guys a little bit better or… you know not everyone is the best of mates down here but we all, you know, we all get along really well and that respect’s there” (Participant 05).By contrast, the survivors were able to identify the relationships that had been formed and could appreciate the camaraderie that existed, but they were less sure of the lessons learned from the experience that might allow them to thrive. They were aware of the hierarchical nature of the organisation and were keen to obtain the approval of others[40, 50] rather than forge a relationship: “… the first time I got up here, I actually looked on all of the pin boards up around the place. There was a notice board … aligning senior players to the younger guys … the whole year went through and nothing got spoken about it” (Participant 16)Those that languished struggled with relationships and were disturbed by the transient nature of the friendships that were formed. They found it difficult to invest their trust and learn from the experience, and were reluctant to sever the relationships from before the transition in case their need for them reappeared[28, 51]:“Oh obviously ... it never gets any easier when you’re missing your friends and your family from home and everything … even though I’ve been up here for a few years it doesn’t really get much easier” (Participant 11).

3.14. Environmental Mastery

- Key to thriving was the ability to learn to control and influence the environment. In particular it involved the mastery of strategies to account for the disparity between expectations and experience. Those that were thriving were able to show they had a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the new environment and were able to access the necessary resources to establish a satisfactory level of mastery. They were not concerned with the separation from the old environment and were more likely to attribute their success to clarity of direction, rather than luck. They could identify the trajectory of their transition and the signposts along the way. In particular they were able to learn from the range of experiences and to apply that understanding to a more positive approach to the challenges of the dislocation: “… at the beginning ... you didn’t know if you were making mistakes[but] now … it’s pretty clear what needs to be done and it’s still hard … but there are clear things to do” (Participant 03).The survivors had a blurred sense of the new environment and lacked the self-confidence to attribute their competence to anything except luck, or compliance to the expectations they had identified. The survivors lacked a sense of direction and were inclined to resign themselves to the requirements of the new environment, rather than to take stock of what was required to thrive and develop mastery. They understood that change had occurred but found it difficult to identify the particulars of the transition: “I think I knew what the changes[were], whether I did them … I knew what was required … but I didn’t really knuckle down” (Participant 19).Those who languished struggled with the new environment and had few strategies to deal with the new challenges. They clung to old habits and lacked the confidence to leave those patterns that had become familiar. They articulated consistent concerns that they felt outside of the new environment, despite being part of it and struggled to find a place where they felt included and in control. They resorted to strategies of mimicry and blind obedience to try to immerse them in the new environment and lacked the subtle insights:“When you first rock up, you think you’d know every player, like you’d think everyone would be as well-known as that, and then you meet a few that you’ve never really heard of and you think, … that’s what I’m going to be” (Participant 02).

3.15. Trust and Commitment

- Trust is an acknowledged factor for well-being[52], and generally described as the ‘willingness to be vulnerable’[53]. It also shares many of the character traits emerging in this discussion such as integrity, competence, consistent behaviour, loyalty and openness[54]. The notion of trust in this context was the ability to let go of concerns and to allocate resources in a timely fashion: to have an understanding of the challenging dynamics of the transition. Similarly, commitment to the future involved an understanding of the process events of the transition and acknowledgement of the next phase of the transition as trustworthy[53]. Those who thrived had a vivid impression of their journey since the dislocating moment and a clear agenda for the next stage. They were able to let go of their concerns and were receptive to the challenge of embracing the new environment. They felt reassured by the solidarity of membership of the group and did not feel susceptible to the pressures that surrounded them: “I sort of cut the old and embraced the new … when I moved here you leave your friends and family, but you’ve got your friends that you know will still stay your friends and you’ve got your friends that you know will move on, and you both go your separate ways with life” (Participant 23).The survivors were less assured and the dislocation was still a poignant reference point for them as they contemplated the next stage of the transition. There was significant hesitation in their willingness to commit to the next phase of the transition; a legacy of their uncertainty through the experience of the transition: “I actually had[started] thinking about going back home and stuff like that, so it was pretty confusing, sort of didn’t know what was happening here whether they wanted me to stay here and stuff like that, so probably that sort of thing where I was a bit confused and, yeah, that’s when I was away from my family … that was the hardest thing I had to do” (Participant 17).Those languishing experienced difficulty in balancing the experience of the transition with a future agenda, and they could not discriminate between strategies that had been useful and those that had not served them well. They questioned the trust they had invested in the process to this point and searched for alternatives in a random exploration of possibilities. They were not willing to let go of the past and found it difficult to commit to the future:“This year I didn’t, sort of expect anything, I just sort of thought ‘see what happens, if it happens, it happens, if it doesn’t, it doesn’t” (Participant 04).

3.16. Discretion

- The ability to plan personal pathways (i.e. to determine the content and scheduling of the transition) was important to positive outcomes. Despite the rigidity of the new environment, the process was highly personalised and the expectations for individuals were wide-ranging. Discretion was often unplanned, and was often the product of the gaps in the system[19]. Those that thrived chose carefully from limited options and learned quickly about the benefits of independent thinking[33, 55]. They were also able to set goals and self-regulate behaviour[40]: “… I’ve had to think more independently … make my own decisions” (Participant 03).The survivors were more constrained and lacked the confidence to exercise their independence. They struggled to interpret advice and feedback[23] and were more inclined to follow the lead of others than to exercise discretion. They were acutely aware of the structures of the new environment and longed for approval for the efforts they made[40, 50]: “I mean when you’ve got senior players sort of saying ‘you should be doing this’ and ‘you should be doing this a lot more’… if you knew that right from the start ... it would it would make you get up to speed a lot better … and I guess now I still don’t know what was required because I never fully made it” (Participant 07).Those languishing were unable to make important decisions, and were limited by the perceived constraints of the new environment. They were dependent on the structure around them and resigned to the pathways outlined for them:“I always had the feeling that home was always going to be there, you know, whether I made it or not, and I remember thinking early that I was going to be there for two years and getting half way through that first year and thinking ’oh well, I’m going to be going home anyway’ ” (Participant 11).

4. Conclusions

4.1. Thriving in a Period of Geographical Dislocation

- This study examined the complex personal issues involved in thriving in a period of geographically dislocating transition. The informing literature and data collected in this study indicates there is a potential for the expansion of capacity for well-being, through the successful negotiation of challenging circumstances[18]. For those faced with dislocation, Nicholson’s model[19] has been expanded to include the particular characteristics and the processes involved at each of the stages[20]. The findings indicate that an interaction of individual resources, social resources and the developmental process can produce positive outcomes. The consequential growth achieved through learning and enhanced well-being is described as thriving. A complex pattern appears where some participants thrive, some survive and some languish. Individuals who thrive:• are self-confident, purposeful and pro-active• have a clear and ordered future focus• are acutely aware of the challenge and attach meaning to engagement• respond positively and confidently to tasks• are positively detached and apply learning with strategic insight• are connected and committed to their support systems.Individuals who thrived in a period of geographical dislocation demonstrated readiness for the challenge through purposeful and selective mastery of the new environment. They were confident, proactive and planned carefully. As they engaged with the tasks of the challenge, thrivers were self-assured and positively detached. They found the tasks of the challenge comprehensible and had a clear and ordered, forward focus. As they progressed, the individuals who thrived developed positive self-concepts, confidence and actively linked with support systems. They had clarity of purpose, a commitment to the process of engagement with the challenging circumstances, and attached meaning to the course of action. In this progression there was an increased willingness and capacity to learn from the experience and to apply the learning to the tasks of negotiating the unfolding challenge. Onward progression of thriving was characterised by an increased awareness of the transition process and connectedness with the new environment. Those who thrived were responsive to the challenge and attentive to the tasks; they employed support systems effectively and continued to build upon the learning that had taken place. This enhanced learning and growth allowed them to more readily identify the transition pathways and engage these with confidence. Those who thrived had mastery of the new environment and controlled complex activities. They planned autonomously and had strategic insight into the resolution of the challenge. They were independent, confidently open and receptive to the future challenges for which they prepared. For those that survive and languish, the stages of the transition are, by definition, poorly resolved. At each stage there are numerous opportunities for timely, pro-active interventions that augur towards thriving. For a full description see Harris et.al[20].

4.2. Reflection

- Thriving promotes the possibility of doing well because of, rather than in spite of, the challenging circumstances. Some challenges are more confronting than others and threaten well-being, and yet some individuals thrive. They have a confident awareness, make meaning from the challenge, learn from the process, and apply the learning to increase understanding. The process of thriving provides exciting possibilities in regard to the enhancement of positive adaptations and timely interventions.Thriving is a dynamic process of positive adaptation. The emerging understanding of thriving draws from a number of contributing ideas, for example resilience and psychological well-being, which describe the suite of personal characteristics and resources that facilitate the trajectory of thriving through learning, awareness and confidence. It will be important to better understand the nature of the resources being accessed and how these have assisted the process, for example, whether the resources encourage learning through enhanced confidence, or vice versa.Measures of thriving still require more attention, as outcomes that appear to be measureable might not provide evidence for the process of thriving. Subjective and objective measures of thriving will provide for a better understanding of the character and process of thriving. While this study was constructed around the challenge of geographical dislocation, the skills and competencies are more universal. While no attempt has been made to generalise from these findings the opportunities for further research might include (a) different participant groups (for example varying by gender and age): are the characteristics and processes of thriving in periods of geographical dislocation identified in this study similar for other participant groups? (b) intervention programs: armed with a better knowledge of the thriving process, how can intervention programs nurture or enhance thriving characteristics?; and (c) other challenging circumstances: are the identified characteristics for thriving applicable in other challenging circumstances?

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML