-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Sports Science

2012; 2(2): 11-15

doi: 10.5923/j.sports.20120202.02

Prevalence of Orthopedic Injuries in Athletes of Rodeo Brazilian (Vaquejada)

Gudson Gleyton Queirós

Hand Institute Maceió, Department of Sports Sciences, José Afonso de Melo, 68. Maceió, Alagoas, 57035-380, Brazil

Correspondence to: Gudson Gleyton Queirós, Hand Institute Maceió, Department of Sports Sciences, José Afonso de Melo, 68. Maceió, Alagoas, 57035-380, Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The rodeo Brazilian (vaquejada) is a genuinely native sport, with a tradition of more than 100 years. Epidemiological study reporting orthopedic injuries arising from its practice could not be found in the present literature. The injury was the most prevalent sprain with 84 lesions(40%), followed by contusion (24%) and strain 39(19%). The Brazilian rodeo vaquejada is associated with a high rate of orthopedic injury and may exclude competitors for long periods of time. Due to the absence of any work done about this kind of sport, the present study demonstrates important and pioneer data regarding the orthopedic lesion nosology of the sport in question.

Keywords: Athletic Injuries, Sports Medicine, Prevalence, Rodeo Brazilian (Vaquejada)

1. Introduction

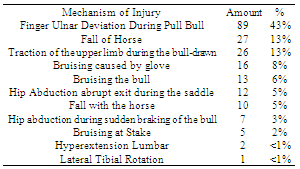

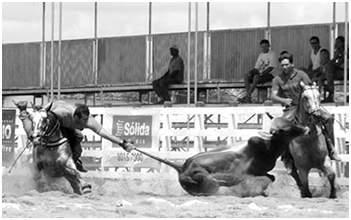

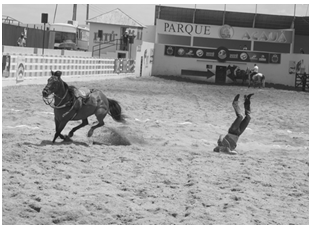

- The vaquejada (rodeo Brazilian) is a genuine Brazilian sport, with a tradition of more than 100 years. In the last ten years has been modernizing and professionalizing. Despite the focus on the North, Northeast and Midwest, are now performed over 1,000 rodeos each year throughout Brazil[1]. Participants contribute to three times per week and travel several miles demand event.The vaquejada is a sport regulated by Federal Law 4.495/98, as well as the profession of "cowboy" by Law No. 10220 of April 11, 2001, which considers the professional athlete "cowboy of vaquejada"[1,2].An event lasts three days with the athlete reaching compete dozens of times. The demands of the sport are short and intense, requiring the athlete's maximum effort for short periods. In this as in most equestrian sports, there is the unpredictability of the accident, and the ability of the horse to move at speeds up to 75 km per hour, with the rider's head at a distance of approximately three meters above the ground, create opportunities for injury serious[3].Races are committed by two athletes, who mounted their horses around the track chasing a steer that often comes out of the stall speed and try to knock him into the demarcation made on the track, usually with ten meters wide[4,5].A race lasts about 12 seconds, depending on the dimensions of the track, handling of the bull by the athletes and speed of the animals.Each "cowboy" has a specific function. The “treadmill” is in charge of positioning the bull the best on the track, quickly pick up and deliver the tail of the ox to his companion. After the fall of the ox in the range, the athlete, his horse, has a responsibility not to allow the cattle, standing up, exceeding the demarcation[4,5].The “handle” is responsible for pulling the bull by the tail and bring it down within the demarcation made in the arena. For good fixation of the tail of the ox in the wrist Cowboy, this is used for a particular product, called "glove of vaquejada." This is made of leather and has straps that hold the handle of the athlete strongly[4].The "glove" has a prominence in its upper part, which the athlete is positioned in the distal radius and ulna, to remain fixed during the pulled bull(Figure 1).The horses run around the track at high speed, and often can be seen athletes droptheir animals violently(Figure 2). The upper extremity of the handle suffers intense stress predispose to injury, as the athlete tries to overthrow the bull that can weighover 660 pounds.

| Figure 1. Cowboy knocking the bull |

| Figure 2. High risk of accident with injury |

2. Material and Methods

- The study included seventy-four athletes, male, mean age 33 ± 9 years. Individuals were addressed during the Stage 1o Circuit of Pernambuco in Vaquejada - (Sovaca Park - State of Pernambuco) and Vaquejada Luke Madeley Park – (State of Alagoas) in April 2009. The instrument used for data collection was a questionnaire with objective and subjective, in which data were collected regarding the athlete's name initials, age, gender, class, position, time of sports practice, prevalence of injuries in the last twenty-four months of work, time off, mechanism of injury, body segments most affected, type of injury and use of materials for individual protection. Inclusion criteria were vaquejada professional athletes and amateurs(handles and / or “tracks”) aged between 18 and 65 years, engaging in sport for at least five years and with a frequency of at least one practice or competition per week. We excluded the category aspiring athletes.The convenience sample was used in the study period. The results were expressed by their frequencies. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations. When the degree of dispersion was high, we used the standard deviation as a measure of the degree of dispersion. We used the chi-square test for evaluation of possible differences between frequencies. Data were analyzed using BioEstat 5.0. The significance level was set at p <0.05.

3. Results

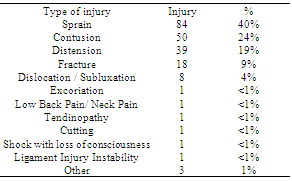

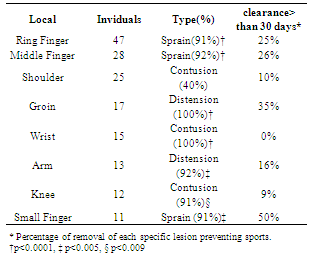

- Among the 50 respondents(68%) were the amateur category and 24(32%) professionals, with a mean time sports 13.0 ± 6.7 years and median of 13 years. Of respondents, 15(30%) act in the position of handle, 1(1%) and belt 58(79%) both. There were 208 injuries in 74 athletes, making an average of 2.8 injuries per athlete over a period of 24 months. The affected sites are expressed in absolute and relative frequencies.The injury was the most prevalent sprain with 84 lesions(40%), followed by contusion (24%) and strain 39(19%). Were 12 different types of lesions(Table 1).

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The vaquejada is a sport very widespread, especially in the Northeast, attracting thousands of participants. Until then, this sport had no epidemiological data to describe the profile of the athletes and the prevalence of injuries. This article has the responsibility to bring scientific data and pioneers on the frequency, location, severity, and the mechanisms that predispose lesions in this unique equestrian sport.In the population studied accidents caused by the practice of vaquejada were frequent. The horse is an animal with characteristics that give it some potential for harm, and this is increased when combining races in which the editor has to master the horse while trying to overthrow the bull that can weigh over 660 pounds.Equestrian activities are considered by some as a sport of high risk[13]. Horseback riding is more dangerous than auto racing, skiing, soccer and rugby[3].In vaquejada handles athletes are constantly and repeatedly subjecting the joints of the upper limbs to large tensile forces, which seems to predispose this segment to overuse injuries (repetitive strain).Report on the occurrence of previous-upper labro lesions, often close to 10% of partial tears of the biceps in athletes subjected to repeated traction, upper limb, were described by Andrews et al., 1985. Our results in 6% of total lesions were found in the upper limb caused by strain in the biceps brachii, this muscle is responsible for 96% of all strains focused arm. From this there is a clear relationship between the tensile forces of the upper limb during the overthrow of the ox and the episode biceps injuries.In the United States of America, demographics of injuries caused by falls in equestrian activities[14] are similar to results reported in this study. The balances show that falls can cause abrasions from mild to more severe fractures affecting a greater proportion of his collarbone and forearm away from the athlete on average 69 days.As previously mentioned, 100% of the lesions of 3rd, 4th and 5th fingers originated the mechanism of ulnar deviation of fingers. There is strong evidence based on the reports of athletes that this injury occurs as a result of ulnar deviation of the fingers caused by the tail of the ox at the time of the pull.When examined the association of the sites of injury, types and removal of sports injury has been observed that the little finger, sprain has caused the largest index of scaring, in about 50%.In the present study, we observed that a considerable proportion (39%) of the athletes do not wear helmets during competition, and (23%) did not use any protective equipment, and regarded of paramount importance. It is known that the helmet is a device that can make a difference regarding the severity of the injury when it affects the head. Perhaps the absence of this simple equipment can negatively influence the injuries caused by head injuries.The falls are relatively common in vaquejada, representing the second most common injury mechanism. In most cases involving athletes handle when the bull abruptly decreases the speed and the rider has his hand looped his tail and can not shake off quickly, or more frequently when the ox-drawn when the athlete does not stand firm on top Horse due to the great weight of the ox or an imbalance generated during the pull.Most athletes who practice vaquejada is willing to continue exercising with pain, reporting only stop when the sports itself considers the serious injury or when there is risk of life, which makes sports great concern in these conditions. This manuscript paper is to present epidemiological data from the risks of injury associated with the practice of vaquejada (rodeo Brazilian) and from this draw the attention of athletes through the federations and associations and the protective measures that can be taken to minimize the risk of serious injury. In particular awareness of the use of helmets to prevent head trauma common in equestrian activities in general[16,17].The analysis suggests that it is necessary to warn the population about the risks involving vaquejada and encourage preventive and education campaigns in an attempt to avoid or minimize the occurrence of injuries in this sport. Accident prevention programs should be implemented both for athletes as for animals. The use of protective equipment and educating athletes can provide a vaquejada with less risk of accidents, making this sport a safer practice.

5. Conclusions

- The vaquejada showed high rates of injuries in this population, sometimes competitors away for long periods. Due to lack of work carried out this kind of sport this study demonstrates important data and pioneers with respect to the epidemiological profile of the sport in question. This research may provide a direction for development of preventive programs and counseling to athletes and professionals involved in this sport.Conflict of InterestThe authors declare that there is any potential conflict of interest in this journal.ThanksProf. Dr. Mauricio Trinity Euclides Filho for their help in the statistics of this journal, Prof.. Dr. Carlos Brandt for reviewing and friend Dr. Rui Ferreira for the tips presented in the moments preceding the interviews with the athletes.PicturesAll photographs and drawings presented in this manuscript are the work of the authors.DeclarationThe authors guarantee that the procedures employed in the study follow the ethical principles governing research with human subjects in accordance with the resolutions of the National Health Council and has been duly approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Biological Sciences and Health FEJAL / Cesmac, Maceio – Alagoas, Brazil, with protocol number 659/09.Financial SupportThis study did not have any kind of financial support for its realization.Conflict of InterestThere were no conflicts of interest for conducting this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML