-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2024; 14(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20241401.01

Received: Aug. 1, 2024; Accepted: Sep. 1, 2024; Published: Sep. 12, 2024

Factors Contributing to Adolescent Pregnancy and the Utilization of Contraceptives amongst Girls Aged 10-19 in Ada East Municipal District, Ghana: A Cross-Sectional Study

Nana A. Owusu Sekyere1, Misheal Yankey2, Rex K. Bonsu3, Maame D. Boateng4

1Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Legon, Ghana Health Service

2Community Health, University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana (University of Ghana, KBTH)

3Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana

4Department of Surgery, Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana

Correspondence to: Nana A. Owusu Sekyere, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital, Legon, Ghana Health Service.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In Ghana, adolescents comprise 22.4% of the population, with teenage mothers reporting 16.1% of all registered births in 2019. The Ghana Health Service has indicated an alarming rise in the number of teenagers in Ghana. Despite the measures taken by Ghana to combat teenage pregnancies, teenage pregnancy continues to be a public health challenge. This study was a community-based cross-sectional study among females aged 10-19 years using a structured interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was an appropriate modification of the WHO [1] standard tool. The results from 189 girls revealed that age, marital status, religion, educational level, and ethnicity showed significant associations with teenage pregnancy. Overall, the study found that age, marital status, education level, ethnicity, and the use of contraceptives significantly influence teenage pregnancy in the Ada East District. It is therefore imperative for the district to expand its adolescent health services and community-based programs to educate the community on adolescent pregnancy and the use of contraceptives.

Keywords: Adolescent, Pregnancy, Contraceptives, Health, and community-based cross-sectional study

Cite this paper: Nana A. Owusu Sekyere, Misheal Yankey, Rex K. Bonsu, Maame D. Boateng, Factors Contributing to Adolescent Pregnancy and the Utilization of Contraceptives amongst Girls Aged 10-19 in Ada East Municipal District, Ghana: A Cross-Sectional Study, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2024, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20241401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The World Health Organization defines adolescents as individuals aged 10-19 years [2], while adolescent pregnancy (A.P.) is defined as pregnancy in girls within said age group [3]. A.P. is a global issue, primarily affecting 1.2 billion adolescents, with 86% residing in developing countries [4]. The World Health Organization reports that annually, around 21 million 15-19-year-old girls in developing regions become pregnant and around 12 million give birth. Teenage mothers (T.M.) face higher complications compared to older women, and complications during pregnancy and childbirth are the second cause of death for 15-19-year-old girls globally [5]. Furthermore, early and unintended pregnancy leads to an enormous loss of educational opportunities for these teenage girls, which virtually results in limitations in life chances [6]. 5.7 million adolescent pregnancies end in abortions annually, with the majority being unsafe abortions [4]. A wide range of factors contribute to high rates of unintended pregnancies and unplanned births among adolescents; lower levels of education, early marriage [7], family-related factors [8], peer pressure, and lack of use or availability of contraceptives to adolescents [9]. Adolescents can prevent teenage pregnancy (T.P.) through abstinence or effective contraception, but barriers exist in assessing contraceptives when abstinence is not feasible. This is because of restrictive laws regarding the provision of contraceptives based on their age. Also, they are faced with an unmet need for sexual and reproductive health care (S.R.H) [4].Adolescents in Ghana comprise 22.4% of the total population [10]. Of all births registered in the country, T.M. were reported at 16.1% in 2019. Ghana's health services have reported a concerning rise in teenage pregnancy rates among teenagers.Adolescents and young women’s welfare have become a major concern for governments and policymakers [11]. In 2000, Ghana established targets to help guide adolescent reproductive health policy, the Ministry of Health and Ghana Health Services has established youth-focused services in health centers, providing a range of sexual and reproductive health services to young people to combat the high rise in teenage pregnancy [12]. However, T.P. continues to be a public health challenge in Ghana, as evidenced by, the 2017 maternal health survey which indicates that 14% of adolescent women aged 15-19 are already mothers or pregnant with their first child. Teenage childbearing is higher in rural areas (18%) than in urban areas (11%) [13]. The 2014 maternal health survey revealed that there has been no significant improvement in the prevalence of adolescent pregnancy in Ghana [14]. Both surveys indicate a decrease in teenage pregnancy with increased education and an increase in childbearing amongst teenagers with no education. 109,888 teenage pregnancies were recorded in 2020, from the Ghana Health Service District Information Management Health System (DHIMS) and Greater Accra had 9,018 of these cases, with Ada East District being the preeminent [15].Ada East District was formerly Dangbe East District in the Greater Accra Region and was established in 1989 by local government instruments (L.I. 1491) with its capital as Ada-Foah. It has a total population of 76,411 representing 1.8 percent of the region’s total population. Males constitute 47.5 percent and females represent 52.5 percent [16]. Establishing risk factors for teenage pregnancy in Ada East Municipality is crucial for better planning and effective programs for policymakers, stakeholders, and healthcare authorities. This study is aimed at determining the factors associated with adolescent pregnancy and the use of contraceptives amongst adolescents in the Ada East Municipality of Greater Accra Region.

1.1. Study Aim

- There have been research articles conducted in several regions in Ghana on the factors associated with adolescent pregnancy, however, there has been no research article on these risk factors in the Ada District. Hence, the main aim of this study is to determine the social, cultural, and demographic factors associated with adolescent pregnancy and the use of contraceptives in Ada East District. This study will, consequently, offer a concrete basis for the increasing prevalence of adolescent pregnancy in Ada East, and as such, appropriate policies and programmatic responses to adolescent pregnancies can be adapted.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

- This study was a community-based cross-sectional study among females aged 10-19 years using a structured questionnaire. This study was conducted in the antenatal and postnatal clinics of the Ada District Hospital, Ada Foah Polyclinic, and Kasseh Polyclinic from April 1 to May 30, 2022. As per the definition of adolescents by WHO [2] aged 10-19 years, the study participants were all female adolescents 10-19 years of age in these selected source populations of the study. Participants were adequately informed about the study's objective and only willing participants were interviewed. Written consent was sought from participants before administering the questionnaire. To ensure privacy and confidentiality, all personal identifiers were excluded, and the questionnaire was secured so that only the investigators had access.Ethical approval to conduct the research was sought from the Community Health Dissertation Review Committee before the commencement of the project. The study excluded anyone refusing to consent to the study for some reason such as an underlying illness.

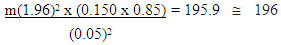

2.2. Sample Size Calculations

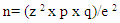

- The required sample size was determined using the Cochran formula shown in the equation below.

where n is the sample size, p is the population proportion (successes) using a value of 0.15 [17], q is the population proportion (failures) using a value of 0.85, and e is a margin of error. Using a confidence level of 95%, the sample size of the z-score value is 1.96 and a 5% margin of error.

where n is the sample size, p is the population proportion (successes) using a value of 0.15 [17], q is the population proportion (failures) using a value of 0.85, and e is a margin of error. Using a confidence level of 95%, the sample size of the z-score value is 1.96 and a 5% margin of error.

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Inclusion criteria for the study were as follows:1. Female adolescents (10-19 years of age).2. Female adolescents who are currently pregnant at the time of the survey and those who have had one or more children.3. Participants who reside in the study area.4. Female adolescents who are willing to participate in the study.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- The exclusion criterion for the study was anyone refusing to consent to the study for reasons such as an underlying illness.

2.3. Data Collection

- The data was collected from pregnant adolescents aged 10 to 19 years using a structured questionnaire. It was administered through face-to-face and telephone interviews in the antenatal and postnatal clinics of the Ada district hospital, Ada Foah Polyclinic, and Kasseh Polyclinic. Females who consented to the study were interviewed using a structured questionnaire by trained interviewers with the assistance of midwives and the nurses in charge of the clinics. The questionnaire consisted of primarily close-ended questions and a few open-ended questions. The questions were specific and structured to address all objectives of the study. The sampling technique was convenience sampling. This was done based on their availability. The structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was adapted from the WHO (Illustrative – questionnaire for interview survey among young people developed by John Cleland) standard tool which was developed to assess the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and youth. Modifications were made to fit the local area.

2.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

- Data obtained from this research was analyzed using Excel and the Statistical Product and Service Solutions V.28 software. The sociodemographic factors, cultural factors, and the awareness of family planning methods and their utilization were statistically analyzed descriptively using frequencies, graphs, figures, and percentages. To evaluate statistically significant results, Pearson’s chi-square Test was used. Pearson’s chi-square was also used to determine the relationships between the dependent variable (adolescent pregnancy) and the individual independent variables.

3. Results

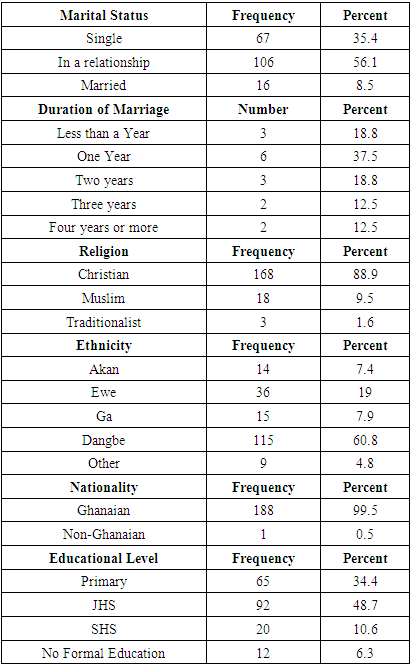

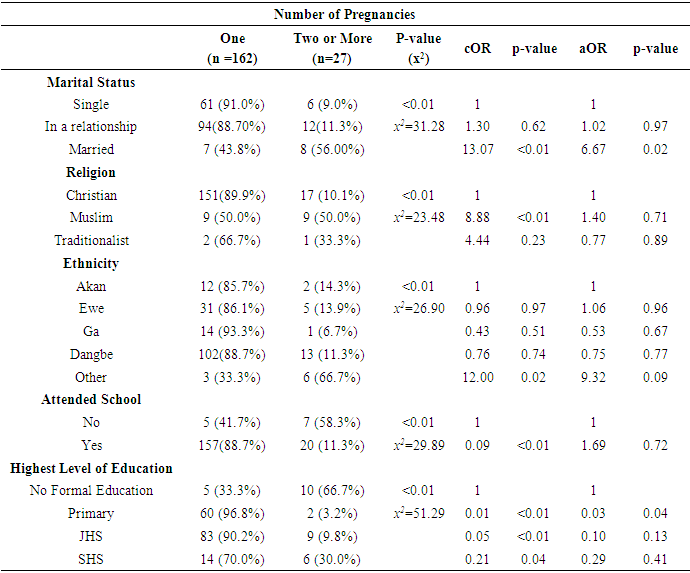

- This study aimed to assess the factors contributing to adolescent pregnancy in the Ada East District in the Greater Accra region. The independent variables were the number of pregnancies while the dependent variables included sociodemographic factors such as age, marital status, ethnicity, religion, and level of education; economic factors and family characteristics and health system factors such as accessibility to services and contraceptives, knowledge of contraceptives and reproductive health. This study enlisted 189 adolescent girls in antenatal and postnatal clinics of the Ada District Hospital, Ada Foah Polyclinic, and Kasseh Polyclinic.Findings revealed that the mean age of respondents was 16.79 (±1.76 years) with ages ranging from 12 to a maximum of 19 years. The majority of respondents were in relationships 106 (56.1%) while 16 (8.5%) were already married and 67 (35.4%) were single. The majority of the respondents were Christians (88.9%) and 60.8 % were Dangbe. Findings also revealed that most respondents had some form of education, 48.7% had at least junior high school education, 34% had just primary education, and 10.6% had senior high school education. With only 6.3% revealing they had no form of education. In addition, most of the girls (59.8%) had never worked a job while 40.2% had jobs previously. Yet only 19.6% of the girls were working at the time of the study with the majority largely in unskilled labor (45%) and with majority earning less than GHS 200 a month in wages (78.8%). Concerning family characteristics, 62.4% of participants indicated that their parents were married, with the majority living with their mother (86.8%) than with their father (77.2%) or both parents. All these sociodemographic factors were revealed to have an association with the number of pregnancies. The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1.

|

|

|

|

|

|

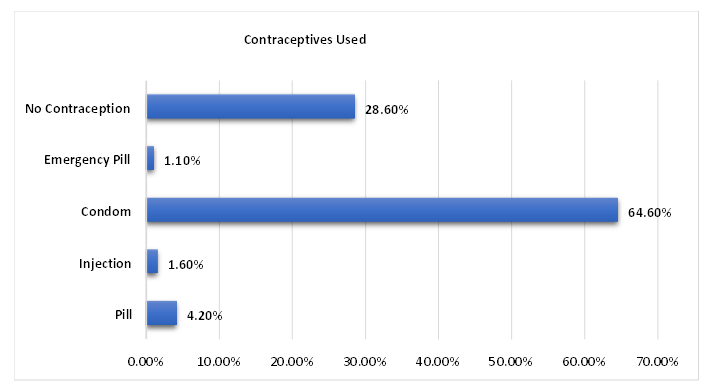

| Figure 1. Contraceptives Used by Study Participants in Ada East District |

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

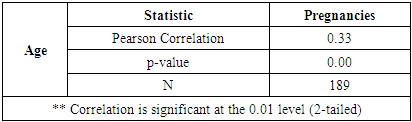

- There were 189 adolescent girls enlisted in this study. They were aged from 12 years to 19 years, with a mean age of 16.79 (±1.76 years). Despite the juvenile nature of the participants’ age, 16 (8.5%) were already married and 106 (56.1%) were in a relationship. Only 67 (35.4%) were not in any form of relationship at the time of this study. This does not differ much from the findings of Stephenson et al. [18] who found that 8.9% of adolescent Ghanaian girls were married. Most of those married in this study (37.5%) had been married for a year or less (18.8%) while 18.8% of them had been married for 2 years and a combined 25% had been married for more than two years. The majority of the participants (88.9%) were Christians, while the rest were made of Muslims (9.5%) and Traditional worshippers (1.6%). Most of the participants (60.8%), in this study area were Dangbe or Ewe (19%). The remaining were Ga (7.9%), Akan (7.4%), and other ethnic minorities (4.8%).The majority of the participants (48.7%) had at least a junior high school education while 34% had just primary education and 10.6% had a secondary school education. There were some individuals (6.3%) who had received no formal education at all. There was a higher pregnancy rate in those who had never attended school (p<0.01). In a meta-analysis study of published and unpublished studies in Africa, among ten articles, it was found that adolescent girls who were not attending school are more likely to start childbearing than those who were in school [19].In this study, people with higher educational backgrounds were more likely to have more children (p<0.01), but this is explained by the fact that educational level seems to correlate with age in this study; a factor that has already demonstrated an effect on birth rate. Reports from Ghana’s Volta Region, Village Exchange Ghana [20] found pregnancy as the main cause of girls dropping out of Junior high School. Once a young girl becomes pregnant, especially in most developing countries, they are more likely to drop out of school [21].Age was shown to be positively correlated with pregnancies (p<0.01). This finding is consistent with those of Uwizeye et al. [22], which showed a significant association between age and adolescent pregnancy. The study found that families with younger household heads exhibited an increased number of pregnancies. The result highlighted the significant influence of marital status, religion, ethnicity, and education on the likelihood of multiple pregnancies. Being married, practicing Islamic religion, and identifying with other ethnic groups, were strong predictors of having multiple pregnancies, while higher levels of education, particularly primary education, provided a protective effect against multiple pregnancies. However, after adjusting for confounding variables, adjusted logistic regression demonstrates that while some associations are influenced by other demographic factors, the role of married women remains particularly robust as they were 6.67 times more likely to have multiple pregnancies compared to the single marital status. Yussif et al. [10] also demonstrated that the majority of Muslim women were more likely to have their first pregnancy at age 19 or less, as compared to Christians. In this study also, it was found that while people usually had one child, people from ethnic minorities were more likely to have more than one child. This however included people with Akan ethnicities (p<0.01).

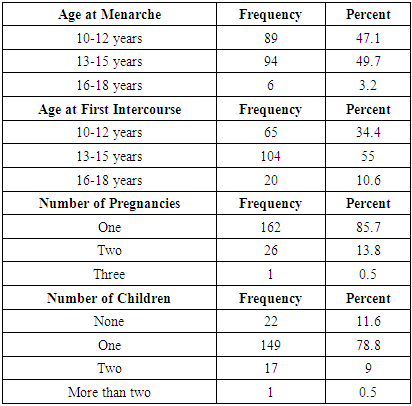

4.2. General Medical Records

- In this study, an almost identical proportion had their menarche between 10 and 12 years (47.1%) and 13 and 15 years (49.7%). Only 6(3.2%) had this experience later between 16 and 18 years. This seems to corroborate other studies carried out in other parts of Ghana. In northern Ghana, the age at menarche was 13.66 years [23] and in Madina, Accra, the mean age was 13.6 years [24].When asked at what age respondents had their first sexual intercourse, it was revealed that most (55%) did so when aged between 13 and 15 years, 65(34.4%) while between 10 and 12 years, and 20 (10.6%) while aged between 16 and 18 years. In Teye-Kau & Godley [25] (2020), the mean age at first sexual intercourse among Ghanaian women was explored and an average of 18 years was discovered, with some outliers according to ethnicity. However, according to a previous study, the median age at first intercourse is 16 years [18]. This suggests that the participants in this study had sex earlier than their counterparts from previous studies. Most of the girls in this study (85.7%) had one pregnancy, while the remaining had two (13.8%) or three (0.5%). Because of the nature of this study, not all the girls had delivered their babies yet meaning 22(11.6%) had no children yet per se, but again, the majority (78.8%) had one child, 17(9%) had two children and only one person had more than one child (0.5%). The mean age at first pregnancy was 16.16 (±1.67 years). These figures are supported by evidence that 11% of adolescent girls between 11 and 15 years have already had a child [26].

4.3. Economic and Family Characteristics

- In this study, most of the girls (59.8%) had never worked a job while 40.2% had jobs before. Yet, only 19.6% of the girls were working at the time of the study, largely in unskilled labour (45%) and with majority (78.8%) earning less than GHS 200 a month in wages. Participants started working at various ages; from 10 to 19 years and the average age of starting work was at 15.04 (±1.95 years). The unemployment figures are not as dire as they appear, considering that most of the girls in this study are about 16 years of age, with a quarter still in school. The general unemployment rate in Ghana is high; in youth, this figure is even higher, with 72% of people between 15 and 32 unemployed as of 2010 [27].In this study, the majority of respondents indicated that their parents were married (62.4%) and it was shown that slightly more of the participants had their mothers alive, but more participants lived with their mothers than their fathers (86.8% vs 77.2%). Fewer participants found it difficult to talk to their mothers about important subjects and on the matters of sex, more participants (35.4%) have never had discussions with their fathers, while only 11.6% had not discussed this with their mothers. This suggests that young girls felt more comfortable discussing important subjects including sex with their mothers more than their fathers. It is important to note that parental involvement has been found to affect early age at first sex and subsequent teenage pregnancy. Living with both parents was associated with lower odds of early sexual intercourse among females [18]. The role of parenting is important in reproductive health counselling as evidenced by the effect on early sexual intercourse and subsequent pregnancies.

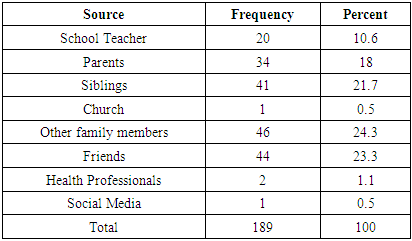

4.4. Source of Information and Knowledge of Reproductive Health

- In this study, the main sources of information about puberty were other family members (24.3%), friends (23.3%), siblings and parents (18%). Other sources included schoolteachers (10.6%) and health professionals (1.1%). Only 0.5% of the population cited church or social media as their primary sources of information regarding puberty. Similarly, the primary sources of information on sex were explored and it was found that other family members were responsible for socialization in 34.4% of cases. Other sources include siblings (19.6%), schoolteachers (16.9%), friends (14.8%), and parents (13.2%) with church and social media contributing only 0.5% respectively. It is worth noting that the proportion of respondents citing parents is concerning. Seeing as most participants mentioned living with at least one parent, it is interesting to note that parents are not the first source of information on puberty or sex. As was established by Stephenson et al. [18] (2014), leaving socialization to friends and other family members in society often promotes risky behavior such as early coitarche.Most participants (95.2%) admit they wish they had received more information about sex and reproductive health, while 9(4.8%) felt they had enough information. In this study, 27% of respondents held the belief that a woman cannot get pregnant on her first sexual intercourse. Also, 29.1% of respondents have the belief that a woman stops growing after she has had sexual intercourse for the first time. This represents nearly 3-in-10 people holding beliefs that can only be described as myths at best. Despite citing sources of information, it is alarming to note that some of these myths are held by participants. This suggests that the quality of information they are receiving from various sources can be considered questionable and more effort should be put in by all parties to ensure that the adolescent girls in the community are getting credible information based on facts.

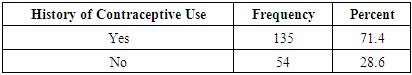

4.5. Knowledge and Ever Use of Contraceptives

- Most of the participants had used contraceptives in the past (71.4%); mainly Condoms (64.6%), Pills (4.2%), Injections (1.6%) and emergency pills (1.1%). The remaining 28.6% had not used any contraception. The reasons being unavailability (24.1%) or no particular reason (75.9%). Most of the participants did not know any other contraceptive methods besides those mentioned above. Only a small proportion knew IUDs (3.2%), female sterilization (1.6%), implants (0.5%), spermicide (0.5%) and other methods (2.6%) like local remedies. In a similar study in Kintampo, Ghana, it was found that only 22.9% used contraceptives consistently, and male condoms were the most known and used contraceptives among adolescents, followed by pills and injections [28]. Oppong et al. [29] (2021) found that only 43% of the adolescent population use contraceptives routinely. These findings suggest a poor knowledge of contraceptives and limited use of contraceptives among this population. Condoms appear to be the most known and used contraceptive in this population, with poor knowledge and use of other contraceptives.

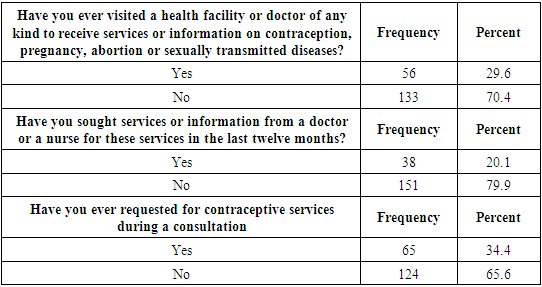

4.6. Use and Perception of Health Services

- In the last 12 months, only 30.6% of adolescent girls in this study visited health facilities for services or information on contraception, abortion, and sexually transmitted diseases. Only 20.1% have gone to health facilities in the last year and contraception services have only been requested by 34.4% of the population in their visits to health facilities. Subjects discussed in such visits have included pregnancy (88.4%) and STIs (64%). The use of reproductive health services can be described as poor, as nearly 7-in-10 have not seen a doctor in this regard in the past year. The subject of discussion in the same period is understandably about pregnancy, but it is worth noting that contraceptives, which are usually included in family planning services have been requested only 34.4% of the time, suggesting a negative attitude towards contraception overall.

5. Conclusions

- Adolescent pregnancy remains a growing issue in developing countries, including Ghana, despite efforts to curb it. Premature pregnancies often hinder socioeconomic advancement, education, and job opportunities. This study identified key sociodemographic factors—age, marital status, Islamic religion, ethnicity, family characteristics, economic status, and education—that increase the likelihood of multiple teenage pregnancies among girls aged 10 to 19 in Ada. Age was strongly correlated with pregnancy rates (p<0.01), though educational status was not significantly linked after adjusting for confounders. The study also revealed poor reproductive health knowledge and limited contraceptive use among the participants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- My profound gratitude goes out to my fellow authors, whose hard work and cooperation have been crucial to finishing this manuscript.

DISCLOSURE

- Not applicable.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML