-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2019; 9(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20190901.01

Community Health Workers Volunteerism and Task-Shifting: Lessons from Malaria Control and Prevention Implementation Research in Malindi, Kenya

Daniel Muia1, Anne Kamau2, Lydiah Kibe3

1Department of Sociology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

2Institute of Development Studies, University of Nairobi, Kenya

3Vector Biology Unit, KEMRI - Wellcome Trust Research Program, Kilifi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Daniel Muia, Department of Sociology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Community health workers (CHWs) operating as volunteers are vital front-line health care workers. They are critical actors in enhancing access to universal health care. The 2006 WHO Report which focuses on human resources for health sees task-shifting as a key response to staff shortage. CHWs thus undertake delegated health care system service delivery at the community level and in most cases for no pay. This paper is drawn from a two years (2015 - 2017) TDR/WHO supported implementation research project which sought to enhance the role of CHWs in malaria prevention and control. The CHWs use community development methodologies to promote work which is otherwise bio-medical. Community engagement is employed not only as a method of passing on critical information on malaria prevention but also as a process of empowering the community to make decisions and to implement and manage change. The CHWs drawing from the Paulo Freire conscientisation process also leads communities to reflect and act on ways of controlling and preventing malaria. The paper also discusses the dilemma of working with CHWs as volunteers whom under task shifting provide services for which compensation could be offered. The study, using a descriptive survey design, collected data from twenty purposively selected CHWs who participated in the project. It found that CHWs are of relatively low socioeconomic status, with only 36.4% having completed primary school education. CHWS are involved in promoting general community health, immunization and sanitation; referring the sick to hospital; and malaria control activities. CHWs perceived their strength as lying in their training and the community recognition and appreciation of their work. CHWs were also aware of the empowerment process that took place in communities out of the community engagement process. While CHWs work as volunteers, they appeared to be keen on getting compensation (Mnyafulo) out of the project. The suggestion was that for sustainability and after the project phase out they could be motivated through some regular stipend as well as uniforms and certification for recognition purposes. This paper concludes that to the extent that task shifting is a reality given the shortage of health staff, policy measures need to be put in place to institutionalize CHWs and their work. This would also entail (and on ethical basis) ensuring some form of compensation for the crucial work done by CHWs in their community units. Continuing capacity building of CHWs also needs to be inbuilt in the county health system.

Keywords: Community health workers, Community engagement, Empowerment, Malaria control, Task-shifting and Volunteerism

Cite this paper: Daniel Muia, Anne Kamau, Lydiah Kibe, Community Health Workers Volunteerism and Task-Shifting: Lessons from Malaria Control and Prevention Implementation Research in Malindi, Kenya, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20190901.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Universal health coverage is seen as a pillar in the global efforts towards the attainment of the sustainable development goals [1]. This is however contingent on all the components of the health system functioning optimally. The 2006 World Health Report focuses on human resources as the key ingredient to successful functioning of health systems. The reality however is that there is shortage of skilled personnel to manage health systems. Globally, the needs-based shortage of health-care workers in 2013 was estimated to be about 17.4 million, of which almost 2.6 million were doctors, over 9 million nurses and midwives, and the remainder represents all other health worker cadres [2]. To cope with this shortage one of the strategies that has been adopted by health systems is task shifting. Task shifting is a process of delegation whereby tasks are moved, where appropriate, to less specialized health workers [3]. Nevertheless, the reality is that universal health coverage in all countries by 2030 is unattainable without strengthening community health systems—enabling community health workers to deliver preventive and curative services, and supporting the empowerment of communities to demand social accountability from their governments and other providers for coverage of quality health services [4]. Again, most of these CHWs are volunteers.The WHO 2016 Global Strategy Workforce report calls upon the International Labour Organization (ILO) to revise the International Standard Classification of Occupations for greater clarity on delineation of health workers and health professions, and in especially given the need to streamline and rationalize the categorization and nomenclature of community health workers and other types of community-based practitioners [1]. Community health workers have increasingly become frontline universal health care workers albeit without pay in most countries, hence their being designated as community health volunteers in most cases. Their role in the health care system has significant bearing on attainment of universal health care. World Health Organisation [3] holds that task shifting is not just a quick-fix solution to a workforce crisis but an approach that has the potential to positively contribute to strengthening health systems overall. Nevertheless the WHO Task force on task shifting cautions in their Recommendation 14 that countries should recognize that essential health services cannot be provided by people working on a voluntary basis if they are to be sustainable [5]. This is the challenge which the interface between volunteerism and task shifting needs to be examined.The term community health worker (community health volunteer in some countries) has come to refer to a cadre of health workers who are selected by the community, trained and work in the communities from which they come. A widely accepted definition as proposed by WHO is that community health workers should be members of the communities where they work, should be selected by the communities, should be answerable to the communities for their activities, should be supported by the health system but not necessarily a part of its organization, and have shorter training than professional workers [6]. CHWs are thus for many, the first point of contact with the health system. Since they live within the community, they know and understand the people and their culture. Further, they possess and carry into communities and homes basic yet critical health knowledge, skills, and tools. Two critical participatory community development approaches are utilised. Foremost is community engagement whereby CHWs involve community members and the households they work with in conceptualizing and understanding the community context so that they could collectively find solutions to the health challenges they face [7]. This entails an open sessions where CHWs share with communities who in turn seek clarifications as necessary. The process of community engagement entails a process for building consensus on the issues of priority, roles to be played by stakeholders and way forward in finding solutions on the issues at hand. In the case of this project this entailed agreement on participation in the project and undertaking malaria control and prevention activities as guided by the CHWs. Secondly, there was the conscientisation process. This is the approach of developing the critical consciousness whereby households’ ability to intervene in their reality so as to change it was developed by the demystification of the causative situations responsible, in this case for malaria [8]. Households are empowered as they are led to discover that such mundane activities as basic hygiene in their households go a long way in the prevention and control of malaria – by eliminating mosquito breeding grounds. This basically entailed getting households to reflect on their material circumstances as related to malaria incidence and through continuous engagement coming to the critical realization that they could actually control and prevent malaria through their deliberate actions at household level. An awakening of the communities ensues as they realize they hold the power to control situations in their locality.Lehmann and Sanders [9] further observe that since CHWs are resident in the communities where they work, they may be a vehicle for scaling up services to underserved populations, addressing geographical, cultural and financial constraints to healthcare seeking. WHO [10] postulates that community health workers should be members of the communities where they work, should be selected by the communities, should be answerable to the communities for their activities, should be supported by the health system but not necessarily as part of its organization, and have shorter training than professional workers. That is where possibly the contradiction starts. CHWs are supposed to be assigned responsibilities and to be supported by the health system, but at the same time be not part of the system – at least in terms of contractual arrangements which might have implications on payment and other benefits. The fact that they are not fully part of the system and are volunteers means that they are exposed to competing loyalties – to serve the health system as well as fend for themselves. This carries the attendant risk of reduced commitment in those times they may not easily meet their livelihood needs. Within the Kenyan context, CHWs serve alongside community health extension workers as part of Level 1 in the Comprehensive Community Strategy that is aimed at organizing communities to take care of their health within the 439 community units established [11]. The Level 1 service is aimed at empowering Kenyan households and communities to take charge of improving primary health care and their own health [12]. This strategy has placed CHWs at the front line staff in health care delivery, although they have also be characterised equally as an invisible backbone working in the shadows of the health care delivery system [4]. CHWs perform many tasks, which include home visits, environmental sanitation, provision of water supply, first aid and treatment of simple and common ailments, health education, nutrition and surveillance, maternal and child health and family planning activities, communicable disease control, community development activities, referrals, and record-keeping [13]. The CHWs in Kenya are expected to serve as volunteers– as service to their community and as part of community participation in their health care delivery and development. Within the Kenya Community Strategy [12], CHWs serve within the “community unit” which comprises approximately 1,000 households or 5,000 people who live in the same geographical area, sharing resources and challenges. On average one (1) CHW serves approximately 20 households. They report to the community health committee (CHC) through the community health extension worker (CHEW), who is the secretary to the committee. They are also linked to the local health facility where they refer cases for review. They are thus the point of contact between the health system and the community. To that extent, despite being volunteers, they could be said to be the vanguard of the primary health care in Kenya.

2. Objectives and Research Question

- This paper is based on a two-year (2015 - 2017) TDR/WHO supported implementation research project which is aimed at enhancing the capacity and role of CHWs in malaria prevention and control in Malindi, Kenya. The emergent question in the course of implementation of the project was the issue of volunteerism (with the context of what was apparently a task shifting situation) and its attendant implications in the course of implementation of the project and subsequently for sustainability purposes. Volunteerism is a widely utilized approach in the delivery of community services, however, there is still the question of how sustainable it is for health systems to ask people to render services in a task shifting arrangement, and therefore for which under normal circumstances should have attracted compensation. Volunteers are real people with real needs and bills to pay. The key questions this paper seeks to address is the extent to which community health workers, involved in task shifting and operating on the basis of volunteerism, could be a useful vehicle in malaria prevention and control, and which is the way forward in terms of addressing the dilemma posed by voluntarism under task shifting.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design

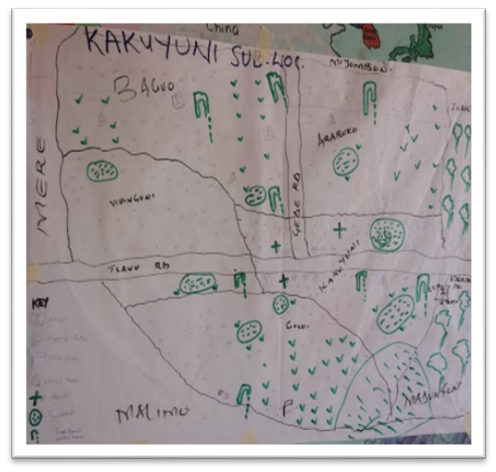

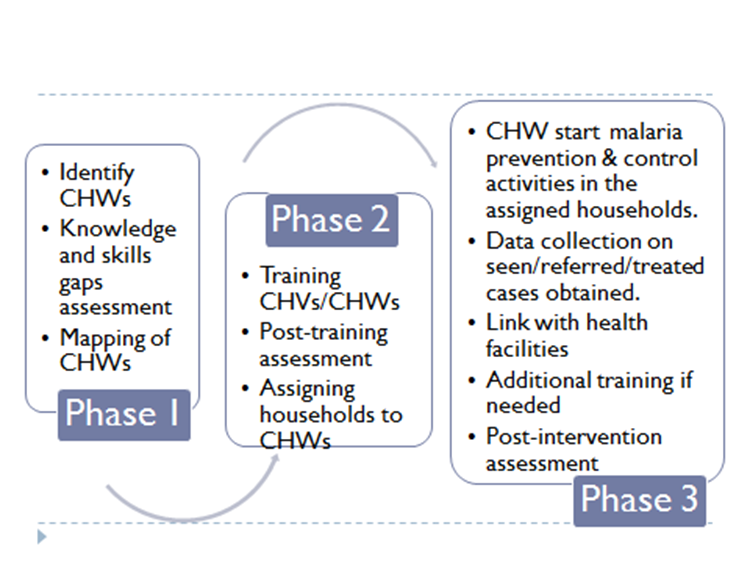

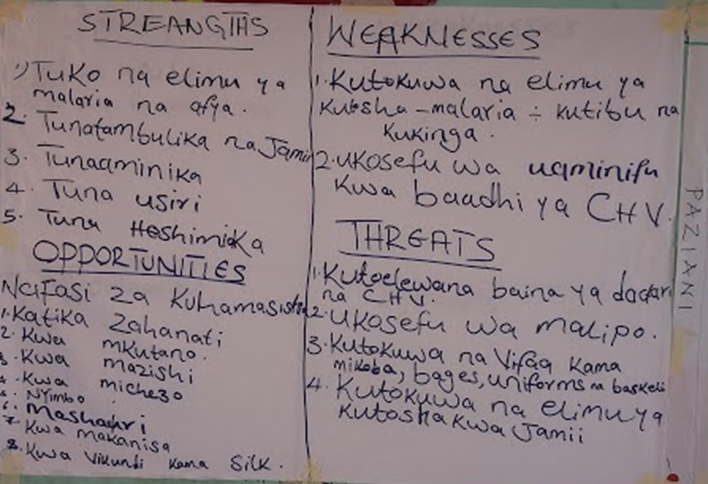

- The study adopted descriptive survey design and used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods and approaches. As an implementation research the project has two components, a research component and an implementation component.Malindi sub-county was purposively selected as site of the study because of it being one of the districts in which the home management of malaria strategy (HMM) was being practiced as well as being a malaria endemic sub-county. Further, the study was being undertaken in Goshi Location, an area purposively selected on the basis of having a relatively high malaria prevalence rate. For operational purposes, two community units in Goshi location (Malimo and Kakuyuni) were covered. The two community units are served by 82 CHWs (Kakuyuni 37 and Malimo 47). Twenty (20) CHWs (11 in Malimo and 9 in Kakuyuni) were selected using stratified random sampling. These two sub-locations have a combined population of 10559 and an estimated 1652 households. The CHWs were supervised by one CHEW per area who was identified from the linked health unit, Malimo and Kakuyuni dispensaries respectively. The inclusion criteria for CHW’s to participate in the study included; consent to participate in the study and in the training; to have served for at least one year as CHWs in the area, and being a permanent resident of respective Unit.Data collection entailed interviews with the CHWs and the households they serve as well as key informant interviews with targeted stakeholders in the malaria control field. Participatory methods such as focus group discussions as well as mapping was also done (see Plate 1 – 2: showing CHWs on a social mapping exercise). The mapping exercise also involved a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats analysis by the CHWs in relation to the functioning.

| Plate 1. Social Mapping |

| Plate 2. Kakuyuni Social Mapping |

| Figure 1. Research Implementation Process |

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of CHS Participation in the Project

- A total of 77 CHWs participated in the study. These include 37 from Malimo community unit and 40 from Kakuyuni community unit. In terms of gender, most CHWs were females (65.7%) while the males constituted 34.3%. With regard to age, the CHWs participating in the project are aged between 22 and 66 years with an average age being 40 years. Majority (83% (64)) of the CHWs are married while only 17% (13) are single. These characteristics compare with the global trend where community health workers, in many countries, hail from modest social, economic, educational backgrounds, and are often women [14-16]. The CHWs in Malindi were largely of very modest formal education status as about 82% of the CHWs has some primary school level of education with only 36.4% having completed primary school level of education. Only 10.4% of CHWs had completed primary school level of education. Generally this level of educational attainment has implications in terms of capacity to acquire and process new information. Any training undertaken with the CHWs had also to take this fact into account in terms pitching the content and thus learning materials had to be simplified considerably. Those who volunteered to serve as CHWs were among those with relative better levels of education. Nevertheless the modest level of education of CHWs is also reflective of the education status in the community units. This also has implications in terms of limited ability to access other livelihood options. Thus serving as a CHWs was offered an opportunity to expect some income through any allowances payable.

4.2. CHWs Level of Involvement in Malaria Prevention and Control

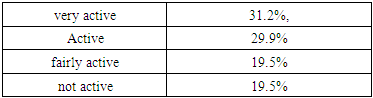

- One of the criteria of inclusion into the project was that CHWs needed to be actively involved as CHWs. The scoping exercise as indicated in Table 1 revealed that about 80% of the CHWs were active in their work.

|

4.3. Volunteerism and the Functioning of CHWs in Malaria Control and Prevention

- A Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis was undertaken with the CHWs to establish the key determinants of their operations. The CHWs were of the view that their strength lay in their relatively better capacity and skills as a result of training on malaria control and health matters (they observed - tuko na elimu ya malaria na afya) as well as in the recognition and appreciation of their work by community members (tunatambulika na jamii). They further saw their mobilization capacity (nafasi za kuhamazisha) as an opportunity they have to serve their community. These findings are also corroborated by [17] study in Uganda where they established that find that CHWs value the opportunity to make a social contribution because of the altruistic drive and the reciprocal appreciation. This is ideally what volunteerism is all about. Nevertheless, the CHWs in Malindi as indicated in Plate 3, pointed out that one of the threats to their service delivery was lack of pay (ukosefu wa malipo). This calls to question the balance between service and volunteerism.

| Plate 3. SWOT Analysis with CHWs |

4.4. Addressing the Volunteerism Dilemma among CHWs

- In as much as CHWs were aware that their work is voluntary, they equally had expectations. The CHWs in Malindi suggested several ways of appreciating them. These included Mnyafulo (pay), uniform and badges, and certificates.a. Payment (mnyafulo) as a way of retaining CHWs servicesThe CHWs expected what they termed as mnyafulo (pay) as reasonable compensation for their work in the project and to the community. Granted there is an ongoing discussion at county level to remunerate CHWs, but the rate and the sustainability issues remain an area of concern. Tanzania has experimented with payment of CHWS. A study in the country suggested that while non-financial factors are important, a commensurate salary is a first step towards increasing the motivation of community health workers [24]. This may be viewed within the premise of [25] motivation theory which does not consider money a true motivator (where intrinsic motivators include achievement, recognition, the work itself, and responsibility and growth); but all the same monetary rewards can serve as an instrument to work satisfaction. Moreover, Amref Health Africa Group CEO, Dr. Githinji Gitahi, observes that more than 50 per cent of Africans cannot access formal health systems and it is community health workers who provide this vital link. Again so far, only Ethiopia, South Africa, Nigeria, Malawi and Rwanda have national CHW programmes which legitimise CHW’s work and offer a sustainable career path [26]. Also one of the largest and most successful community health worker programmes can be found in Brazil, where the Brazilian Family Health Programme has been successful in institutionalizing and mainstreaming community participation; and community health workers have been integrated into health services and are paid wage [5]. Thus as task shifting becomes a reality in light of challenges with resources for health sector, a remuneration system is imperative so as to assure sustainability of using CHWs within the health care system. Of the experience of working with CHWs in Malindi has revealed that the CHWs are actually the backbone of the health delivery system. They support virtually all preventive health service delivery at the local level, including assessing and referring cases that need review to the local health units. In terms of investment of time, it appeared the CHWs were actually on full time employment as they undertook the multiple roles which were required of them, including periodically visiting and taking care of their assigned households within their community units. This left little time for them to pursue their livelihoods and thus the ethical concern – should such “workers” not be compensated?Moreover, the CHWS see themselves as putting in just as much work as most other health service delivery workers, they may also question why they work and are not paid, their being volunteers notwithstanding. This may be looked at within the premise of work equity theory whereby individuals assess the tangible and intangible costs and benefits of their own work against those of others and if feeling unfairly treated may respond with low commitment and turnover [27, 28]. On this basis, so as to keep the commitment of CHWs and for sustainability of health care systems it would be prudent to offer them some remuneration and or at best fit them within the health care systems budget cycle as part of the human resource of the system. The Malindi implementation project offered the CHWs a monthly stipend of Ksh. 2000 as a token of appreciation over the six months they were supporting the implementation process and this to a large extent warded off attrition. The sustainability of their operations after phase out could still be a concern. However the partnerships established with the County health system hopefully will translate into their continued service. The sub-county health system managers indicated they were exploring options of motivating the CHWs across the county.b. Uniform and badgesThe CHWs in the study raised the issue of identification and recognition. In as much as the CHWs served within their community and are literally appointed by their community, their take was that having uniforms and identification badges would enhance their status. They would be much more easily recognized. One said, uniform itafanya tutambulike zaidi (uniforms would make us be more respected). The import of this was that generally the uniform would symbolically confer higher status to the CHW beyond their locality and also recognition in the spaces beyond the community in which they serve. This could be placed with the ambit of intrinsic benefits accruing to the CHWs. According to Manzi [29] Tanzania is experimenting with monetary rewards for CHWS (paid CHWs while at the same time retaining volunteer CHWs) and has also provided them with uniforms. In Malawi the CHWs observed that the uniforms we wear are our identity [30]. Greenspan [31] also documents that the Tanzanian CHWs besides in some cases getting monetary rewards from their clients, they receive non-material rewards, most important, the recognition and encouragement (the society recognizes you and you get fame). It is within this context the Malindi CHWs sought uniforms as an outward sign of their service to the community which would in turn attract admiration and respect. The concern however would be one of setting a path towards formalizing an otherwise noble call to serve the community. But possibly given their immense sacrifice, allowing them to have uniforms could be a small sacrifice by the formal health system. In any case it is standard practice in Kenya for frontline staff to wear uniforms.c. CertificatesThe CHWs receive training as part of capacity building by the various actors they work with besides the formal health system. The concern is that in many cases they are not awarded any certification to attest to the knowledge and skills received. Globally certification is a mark of recognition. Whole most of the CHWs may never seek to be employed, their take was that being awarded a certificate for their training and also involvement in projects would give them something tangible as evidence of their work. Again in as much is this might be seen as an indirect reward, it should also be seen as attestation of the investment the CHWs make in pursuit of service to their community.

5. Conclusions

- The implementation research has revealed that CHWs have largely the same attributes as the rest of the members of their community in that their socio-demograhics largely mirrored those of the community they served. They undertake a multiplicity of roles in support of the community strategy to deliver primary health care at the community level. Their volunteering however should be looked at within the context of a world with real needs where they also have families to take care of. A model that incorporates a stipend on top of any other non-tangible reward would go a long way in ensuring sustainability and that CHWs serve in a system that cares about them and their basic welfare. In any case as rational social actors, CHWs will still need to be assured they have a net benefit of serving their community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This paper is as a result of an implementation research project undertaken in Malindi Kenya with the support of TDR/WHO. An edited version of the paper was presented during the World Community Development Conference (WCDC2018) held at Maynooth University, Ireland, between 24th and 27th June, 2018.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML