-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2017; 7(5): 123-132

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20170705.01

The Artistic Performance and Social Significance of Nso Incantations

Andrew T. Ngeh1, Ngeh Ernestilia Dzekem2

1University of Buea, Cameroon

2University of Bamenda, Cameroon

Correspondence to: Andrew T. Ngeh, University of Buea, Cameroon.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper sets out to investigate whether the incantations performed by the people of Nso in the North West region of Cameroon are relevant in the contemporary society that is mostly characterized by enormous scientific and technological innovations. The study contends that “Lamnso” which is the language spoken by the Nso people of the North West region of Cameroon constitutes a reservoir and cultural quarry for Orature. The culture it houses is rich in oral literature even though it is being threatened by globalization, cultural imperialism, neo-colonialism and modernism. It is for this reason that, this study, considers the examination of Nso oral tradition as an integral global concern. In order to attain the objectives of this study, the ecocritical and sociological readings imposed themselves on these incantations. The study further argues that though most material of Orature comes from the past and was commonly seen to be rooted in the distant past, it can still be used to interpret contemporary and historical realities because it reviews the past, evaluates the present and anticipates the future. Raph Perry notes in the Foreword to African Culture: The Rhythms of Unity that “The past as embodied in contemporary adults is both the bed of reactionaries and springboard of innovations” (110). It is in this light that this study contends that the traditional society and the modern one are mutually inclusive entities with regard to African oral literature.

Keywords: Performance, Relevance, Incantations, Poetry, Contemporary and Context

Cite this paper: Andrew T. Ngeh, Ngeh Ernestilia Dzekem, The Artistic Performance and Social Significance of Nso Incantations, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 123-132. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20170705.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction and Background to the Study

- The main concern of this study is to investigate the contributions of African oral literature in the interpretation of contemporary realities within the Nso socio-cultural setting. In this regard, the incantations studied in this paper are a response to social, economic, cultural and philosophical concerns. This investigation is crucial because of the transcendentalism of African oral literature. Given that African oral literature in a globalised context is a response to the social, economic, political and cultural concerns of the contemporary society, it can be used to address societal concerns. Jan Vansina in Oral Tradition as History quotes the following Akan proverb from Ghana: “Ancient things remain in the ear” (45). The implication of this proverb is that though it is rooted in the past, it is linked to the present and can in turn be used to interpret the future. In this regard, one of the contentions of this study is that African oral literature reviews the past, evaluates the present and anticipates the future. As Ngugi wa Thiong’o has contented in Homecoming, (1972:39), “Time present and time past are both perhaps present in time future, and time future contained in time past.”Though oral literature is old, it is shared by everyone in the community since it defines group identity and has values that manifest in people’s actions. Kashim Ibrahim Tala and Henry Kah Jick in their article “Lapiro De Mbanga and Political Vision in Cameroon” have argued that since oral literature is a changing activity, the oral artist “finds that he has to transcend his immediate cultural environment to embrace the concept of a new nation” (34). Seen from this perspective, this study borrows a leaf from Lupenga Mphande in the introduction to the Encyclopedia of African Literature, who points out that,Despite the ravages of slavery and colonialism on Africa’s political, economic and social systems, the continent’s cultures and aesthetic sensibilities remain independent and vibrant, particularly in the orally based forms of cultural expressions. Although African societies have developed writing traditions, Africans are primarily an oral people, and it is that tradition that has dominated the cultural forms created on the continent. (579)The implication of the above citation is that African oral literature has the sense of being simultaneously old, almost timeless in its themes and forms, and new, the latest addition to global literary culture. The same source notes that “forms of creative expression developed in Africa outside the orbit of colonialism and that continent’s living heritage of oral literature bears witness to this autonomous tradition” (xi).

2. The Nso People, Origin, Location, Occupation, Beliefs, and Administration

- According to Lamnso-English Dictionary, Nso refers to an ethnic group which left Rifem in 1370 under the leadership of Ngonso. It also refers to the region inhabited by the Nso people. The people from this part of Cameroon have a passion for their culture and the celebrations of their culture are manifested dance, songs, legends, initiation, incantations and even the way the people dress.In his Towards an African Literature: The Emergence of Literary Form in Xhosa Lupenga Mphande points out that “if literature reflects the society which produces it, then understanding the social forces at work in that society is vital to appreciating that society’s literature” (viii). Since this study borrows a leaf from this assertion, it is considered pertinent for us to have some knowledge about the Nso society.Nso is found in the North West region of Cameroon. Its division is Bui which constitutes one of the largest and densely populated ethnic groups in Cameroon. More than four fifth of the Nso people is farmers. Beans, maize and potatoes are cultivated both for subsistence and commercial purposes. The men mainly preoccupy themselves with farming, hunting expedition and the tapping of raffia wine. Nso is the largest Fondom in the Bamenda grassfield. It occupies the Eastern region of the North West region of Cameroon, lying between latitudes 5.60°N and 6.25N and longitude 10.20°E and 11.50°E. The division is bordered to the West by the Fondom of Kom, to the East by the Bamum dynasty, to the South by the Fondoms of Ndop and to the North by the Mbum villages of Donga and Mantung division. Like many African languages Lamnso (the language spoken by the people of Nso) is not well written and studied. Until recently, the best medium of communication of Nso Orature has been the spoken word. The various genres of Nso oral literature before now have been preserved in the people’s memories, and it was only during performances that they were communicated verbally to their audiences. These trends are experiencing change since researchers have started recording and preserving some of the oral genres in print and using other equipment of the electronic media. There are literacy centres for the study of Lamnso in most villages of the Nso Fondom.The Nso people have a mixed economy. They practice subsistence agriculture. A greater population of Nso is involved in farming and cattle rearing due mostly to the influence of the Fulanis in the area. They rear animals like cows, goats, pigs and also do poultry. A smaller proportion of the population is involved in trade and craft alongside farming to earn a living. Their main food crops are beans, maize, Irish potatoes, plantains, cocoyams, yellow yams and groundnut. The Nso people have coffee as their main cash crop. The Nso oral traditions hold that its dynasty originated from Tikari, a plain in the region of Mbam River and has occupied the present area since 1370 and are perhaps one of the oldest dynasties in the North West region of Cameroon. The people of Nso believe that the dead who have stubbornly refused to die regulate the activities of the living. The communication between the living and the dead is done through rituals, incantations, the pouring of libation and ancestral worship. In spite of globalization, modernism and colonialism which find expression in Christianity, the Nso man still holds very tight to his cultural values.The Nso people cherish their culture and traditions and these institutions are headed by a traditional administrator known as ‘Fon’. He is assisted by sub-chiefs known in the Nso land as Shufaáy or Fai. These are quarter heads that assist the Fon in the day to day running of the administration. In addition to these are the regulatory authorities called the Nwerong and Ngiri that discipline deviants and non conformists in the society and check the excesses of the Fon. The fact that these sacred societies are for men only demonstrates the male dominance of such a society. It is these titled men (Fon and Shufaáy) who perform these rituals and incantations in the Nso society.

3. Conceptualization

- For this study to be properly comprehended, it is important to define some key concepts. This is in keeping with Bernard Fonlon’s submission in “The Idea of Literature” that the first principle of any scientific discourse is the definition of one’s terms or concepts so as to know “clearly and precisely right from the start” what these terms or concepts mean (179). These terms are “Performance” “Incantations” and “Contemporary”. The Encyclopedia of African Literature defines Performance as “…a contested concept with no agreed-up definition and calls into question conventional understanding of tradition, repetition, mechanical reproduction, and ontological definitions of the social order and reality” (582). The Collins English Dictionary defines the same concept as “the act, process or art of performing an artistic or dramatic production”. Consequently, this paper approaches performance and text from a balanced perspective that avoids projecting incantations as a fossilized artifact, or the performer and audience as passive, disengaged bystanders. Thus performance is viewed here from the process paradigm which is temporal, participatory, and interactive.The Cambridge Advanced Learners Dictionary defines incantation as “(the performance of) words that are believed to have a magical effect when spoken or sung” Nol Alembong in Standpoints in African Orature writes that “By their very nature, incantations stem from ritual performance…. Given that rituals are part and parcel of religious worship and that ritual performance usually occasions the rendition of incantations, religious worship is a binary activity consisting of ritual performance and the rendition of incantations. (71). He defines incantations with focus on the activity and occasion: An incantation is a verse form, the words of which are believed to have a magical effect when spoken or chanted during the performance of rituals or any other occasion that calls for the intervention of the supernatural in human affairs. This verse form manifests itself in such categories as blessings, curses, invocations, prayers and spells. (72)Therefore, the art of chanting incantations is a composite activity which combines ritual performance and the production of context-based utterances by a defined live performer in the presence of a defined live audience. Alembong identifies four main levels of ritual performance which may occasion the rendition of incantations in Africa. He observes that, “These levels have to do with the individual or groups of individuals belonging to a guild or some form of association, the family, secret societies, and the community” (72). According to Kashim Ibrahim Tala in Orature in Africa, “Incantations are magically-oriented formulaic expressions. They are saturated with mystical powers and loaded with images that are highly mythopoetic. They are used to ward off evil, to evoke evil on enemies, to curse offenders, and to boast one’s personality” (52). This definition emphasizes the functionality of incantations.What is common in these definitions is that both reiterate the fact that they are word imbued with magical powers performed during specific occasions for specific purposes by specific individuals in the presence of a specific audience. Tala further points out that “they are used by man to solve the spiritual, economic and social problems confronting him …they constitute a vital force in the survival of men” (52). Nso incantations fall within the paradigm of Alembong and Tala’s definitions of incantations and this is the direction adopted by this paper. It is also important to observe that Nso incantations are believed to have spiritual, religious, political, economic and social functions. This method used in the realization of incantation brings out ritual, performance, audience, performer and occasion as major elements in the production of this oral genre. Ruth Finnegan in the text quoted above defines oral literature with focus on performance: Oral literature is by definition dependent on a performer who formulates it in words on a specific occasion – there is no other way in which it can be realized as a literary product…. The significance of performance in oral literature goes beyond a mere matter of definition: for the nature of the performance itself can make an important contribution to the impact of the particular literary form being exhibited. (2-3) This study closes ranks with Finnegan’s submission and contends that, the performance of Nso incantations gives the performer and the audience the channel to respond to social, moral, economic, political and cultural issues of the society. In other words, the social, political, cultural and economic concerns of the Nso society find expression in Nso incantations.On its part, the word ‘contemporary’ as defined by the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary means “existing or happening now (325). This study perceives the word ‘contemporary’ as an on-going, modern setting, process in a society.

4. Statement of the Problem

- Some scholars are of the opinion that African oral traditions are outdated, obsolete and anachronistic. The English Literary critic Fredric Jameson, for instance, has argued that “Orature is obsolete and if remnants of it exist at all today it will be under marginalized and declining conditions” (qtd in Jick and Ngam, 4). But the present study takes a contrary position and argues that Orature is not a fossilized form of a primitive past of a people’s culture, but it is a vibrant aspect of a people’s existence that can be used to review the past, evaluate the present and anticipate the future. Ruth Finnegan in Oral Literature in Africa shares this view when she writes that, “oral poetry is not an odd or aberrant phenomenon in human culture, nor a fossilized survival from the past, destined to wither away with increasing modernization” (3).

5. Research Questions

- Given the above problematic, the following research questions are crucial in the understanding of this paper:(a) What is the relationship between oral literature and society?(b) What is the place of aesthetics in Nso incantations?(c) Can African oral traditions still be relevant in the present global dispensation?(d) Can incantations address socio-political, cultural and economic concerns?

6. Hypothesis

- In view of both the statement of problem and questions raised, the argument of this paper is built around the hypothetical contention that while Western oral art forms may have become obsolete, outdated and anachronistic, African Orature is alive, dynamic, healthy and sensitive as they can be used to review the past, evaluate the present and anticipate the future. This art form is elastic and preoccupies itself with both public and private matters. David Kerr in Dance, Media Entertainment and Popular Theatre in South East Africa remarks that,The stereotype of the rural folklore informant cut off from the modern world, is no longer valid. That world impinges on his/her everyday life and needs to be dealt with. What is required is an equal exchange between investigators, interacting from different cultural perspectives so that the folk informant becomes not simply the subject of the research but the agent of his/her involvement in cultural creativity, consciousness and cultural transformation. (240)This study hopes to substantiate this contention with the use of Nso incantations to argue that though incantations like other variants of oral literature are mostly rooted in the distant past, they are also relevant because they become interpretive tools of the Nso/ African contemporary society. African oral literature in general sustains, maintains and preserves the history, culture and identity of individuals at all times through performance using components such as proverbs, myths, songs, incantations, storytelling and riddles.

7. Methodology and Theoretical Framework

- The incantations we have selected for this study are presented as closely as possible to the way they were originally performed by the performers who also acted as informants. Some of the data was first collected by one of the researchers when she was writing her post graduate dissertation titled “The Ideological and Aesthetic Significance of Incantations: The Example of the Nso Tradition”. Between January 2014 and November 2016, one of these researchers being of Nso origin also recorded other incantations during live performances on different occasions in Lamnso (the language spoken by the Nso people) and one of them is on “Numerous Untimely Deaths”. This incantation was recorded live among others and translated into English. In order to attain the objectives of this study, the ecocritical and sociological critical criteria were employed in the interpretation, evaluation and analysis of the Nso incantations. Consequently, these critical and analytical tools were employed in order to ascertain the relevance of Nso incantations in modern and contemporary contexts. A plethora of literary theories exists in literary criticism; for example, Marxist critical theory, new historicism, post modernism, psychoanalysis, Black aesthetics and formalism. However, this analysis is informed by both the eco-critical and sociological theories since the study borders on the Nso society and its environment.Even though nature writing and studies in nature have existed for some time now, ecocriticism as a literary theory is just making its debut in literary discourse. The word ecocriticism has its origin from the articulations of the American scholar Cheryll Glotfelty who coined it to refer to a theory that examines the way nature in general is presented in literary works. Also prominent in ecocritical discourse are names like Harold Fromm, Lawrence Buell and Michael Branch.Though ecocriticism has influenced critical perspectives such as Marxist critical theory, feminism, postmodernism and post colonialism, it has some basic tenets that undergird its discourse. Ecocriticism looks at the relationship that exists between man and his natural elements that make up his environment and how this is presented in literary works. Secondly, it focuses on the attitude of man toward these natural elements and how he is affected by them. This theory therefore emphasizes the fact that plants, animals and other elements of the ecosystem have and deserve their rightful place within the environment. Finally, ecocriticism reiterates the greening of landscape; thus, there is emphasis on the word “green” wherein one hears of words like green Sahel, green cities, green peace, green glass, green revolution, shades of green, global green and others. By laying a lot of emphasis on “green”, ecocriticism symbolically stresses originality, peace, birth and rejuvenation. Consequently, the focus is on the natural coexistence between man nature and his environment. According to Richard Kerridge,The ecocritic wants to tract environmental ideas and representations wherever they appear....Most of all, ecocriticism seeks to evaluate texts and ideas in terms of their coherence and usefulness as responses to environmental crises. (qt in Garrard 4)Kerridge’s submission above is an indication that ecocriticism lays emphasis on the coexistence between man and nature as it is incumbent on man to protect and preserve his environment because its depletion and degradation threaten the very existence of human beings.In addition to the above tenets of ecocriticism, this theory also dwells on issues of eco-activism, and looks at the ways literary critics view issues of equity and justice and their place in environmental concerns. The Free Library in the introduction to its “Special Issue Ecocriticism Part 1” states:According to Levin (1999:1097) ecocriticism is marked by a “tremendously ambitious, intellectual, ethical, political and even (sometimes) spiritual agenda.” He (Levin) states that ecocritical dialogue often aims at transforming the human environment and ecological consciousness by guiding the historically egocentric Western imagination towards a newly emerging ecocentric paradigm. (http://.thefreelibrary.com).Ecocriticism and the sociological theory are the analytical tools utilized in this study. Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm define ecocriticism as “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” (xviii). Jelica Tosic in “Ecocriticism – Interdisciplinary Study of Literature and Environment” says that “Ecocriticism is concerned with the relationships between literature and environment or how man’s relationship with his physical environment is reflected in literature” (qtd in Fondo, 97). William Rueckert in “Literature and Ecology” sees ecocriticism as the application of ecology and ecological concepts to the study of literature, because ecology as a science, as a discipline, as the basis for human vision has the greatest relevance to the present and future of the world” (qtd in Fondo, 97). Ecocriticism studies the relationship between literature (spoken or written) and the natural environment. This study hopes to demonstrate that Nso incantations refer to social and cultural distinctions while presenting the fauna, flora and the physical surrounding. The main aim of ecocriticism in the context of this study is to ascertain a harmonious and symbiotic union between man and the natural environment that surrounds him. Through literary ecology, the study hopes to highlight the economic significance of traditional or indigenous knowledge inherent in Nso incantations.The sociological approach to literary criticism emphasizes the symbiotic relationship between literature and society. Literature taps from society and society in turn influences literature. Given that the Nso incantations emanate from a particular sociological background which is the Nso cosmic, this study intends to establish the relationship between the Nso oral tradition and its society. Proponents of this critical approach are: Abiola Irele, E. Emenyonu, Chinweizu, O. Jemie and I. Madubuike. Establishing a relationship between sociology and literature, these critics affirm that like sociology, literature is basically concerned with man’s social world, his adaptation to it and intention to transform it. Thus, the incantations studied in this work are essentially meant to reshape the Nso cosmic.

8. The Social Background and Performance Principles of Nso Incantations

- The Nso people refer to incantations as ‘Kiŋka’. It is not easy to trace its origin and historicity, but it is obvious that the act of chanting incantations around shrines is not a recent development in Nso history. ‘Kiŋka’ (incantations) among the Nso is as old as the Nso history goes. Unlike proverbs, riddles, folktales and songs, incantations have limited audience and performers. The kind of occasion or event determines the performer and defines the audience. Nso oral culture reveals sufficient evidence that the act of chanting incantations has existed in Nso traditional life in the primordial past. Incantations like other elements of oral tradition come from the past and respond to the changing times. The titles of the three oral poems or incantations under reference in this study illustrate the fact that they have a contemporary relevance. The poems under study are: “Drought” “New Churches” and “Numerous Untimely Deaths”. These incantations are poetically appealing and ideologically fulfilling. The three are incantations because they are performed when the community disagrees with what is observed. Ruth Finnegan in her, Oral literature in Africa writes that,There is no good reason to deny the title of literature to corresponding African forms just because they happen to be oral. If we do treat them as fundamentally of a different kind, we deny ourselves of a fruitful analytic approach …. We need of course to remember that oral literature is only one type of literature, a type characterized by particular features which have to do with performance, transmission, and social context with the various implications these have for its study. (25) Incantations fall under religious poetry and Finnegan identifies three main ways in which poetry can be regarded as religious: “Firstly, the content may be religious, as in verse about mythical actions of gods, or direct religious instruction or invocation. Secondly, the poetry may be recited by those who are regarded as religious specialists. Thirdly, it may be performed on occasions which are generally agreed to be religious ones” She clarifies that “These three criteria do not always coincide” (67) Nso incantations are considered as religious poetry since they are about mythical actions of gods. They are invocations performed around shrines during specific occasions to invoke the spirit of the ancestors to intervene in a particular situation especially crisis situations.

9. Textual Analysis

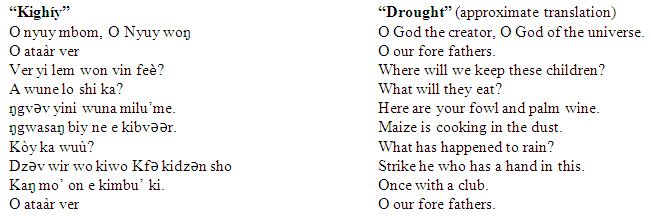

- According to Finnegan, “oral poetry is not an odd or aberrant phenomenon in human culture, nor a fossilized survival from the past, destined to wither away with increasing modernization. In fact, it is a common occurrence in human society”. (3)In line with Finnegan’s submission, this paper is concerned with the application of incantations to demonstrate that they have a legitimate place in the modern culture of Cameroon and are relevant to the contemporary Cameroonian society, in particular especially if the indigenous knowledge that they harbour can be utilized in all sectors of the economy. The point emphasized here is that this kind of legitimacy does not only come from its original Nso (African) quality and flavour but from its original Nso contemporary existence and it is here that incantations performed in Lamnso assume a wider social and cultural significance.Andrew T. Ngeh and Nformi Dominic Nganyu in “Folklore and Commitment in Anglophone Cameroonian Poetry: A Study of Bongasu-Tanla Kishani and Nol Alembong opine:The people of Africa, like all other peoples of the world are inseparable from their history and culture, for their history is the record of what they did, thought and said; and their culture is the totality of the ideas, concepts and values that characterize their societies. These cultural elements are manifested in their literatures (oral as well as written), religions, social, economic and political institutions, music and dance, arts and drama, and their languages- all these have been and are still profoundly influenced by their environments. (16)The implication here is that man cannot survive without his past because the short cut to the future is via the past. One of the arguments raised in this paper is that the relationship between the individual, his past and society constitutes the main focus of oral literature in general and incantations in particular. The social, economic, cultural and political concerns in a society can determine its literature, and that literature can change the direction of the lives of its producers. It is from this perspective that this study becomes relevant to the performance of Nso (Cameroon) incantations in a contemporary context.In the pre-colonial Africa, oral literature functioned as a medium of education, entertainment and the revival and redemption of society. Our focus in this study rotates around these same functions. In the contemporary context, Tala perceives the oral artist as one operating in “a heterogeneous society with no unified body of norms and with no clear-cut expectations from its members” (164) Jick and Ngam in “Performance and Relevance of Kom (Cameroon) Riddles in a Contemporary Context” explain that “this means sensibility and a new medium” (12) In line with this assertion, Emmanuel Ngara contends: The dynamics of political struggles and social change affect the content and form of works of art so that if we are to understand fully and appreciate the rise, development, concerns and styles of the literature of a nation, we must see that literature in relation to the history and struggle of its people and in relation to the various ideologies that issue from socio-economic conditions. (29)From the foregoing submission, therefore, this study makes bold to argue that the traditional artist who was originally limited to the confines of his village now develops orally transmitted material into global commodities. Thus, the relevance of the study of the performance of Nso incantations is essentially meant to demonstrate and ascertain whether they are relevant in a contemporary context or are still basking in the euphoria of their distant past. This is one of the fundamental questions that this study grapples with.Religious poetry in general involves all aspects of society and therefore difficult to understand unless one has a good knowledge of the society from which it is produced and performed. In this regard, Finnegan emphasizes that “In any case the religious significance of a poetic product can only be assessed with a detailed knowledge of its social and literary background, for only then can one grasp its meaning (or meanings) for composer, reciter, and listeners” (200).Nso incantations emanate from the background of the Nso society and incorporate all the ways of the Nso community including its physical, socio-cultural, metaphysical, philosophical and political backgrounds. For instance, the Nso people see children as the future of the community since their presence symbolizes and ensures continuity. The community feels threatened when they register numerous untimely deaths within a limited period. The general conception and perception about life is that the children should bury their parents and when the reverse is the case, it becomes a call for concern. In the first incantation in this study, the focus is on the occurrence of a drought which in science may be viewed as the vagaries of nature, but within the Nso cosmology, it is not a natural occurrence and something has be done to bring it to an end. “Kighiy” which is translated as ‘drought’ is performed against the backdrop of this misfortune. The views of the performer are expressed in his invocation which is an appeal to both gods and his ancestors to wake up and intervene thus:

In Nso cosmological system, there is nothing like a natural occurrence. Just as someone can withhold the rain, so too can someone unleash drought on the people with its devastating consequences. It is against this backdrop that the performer during his performance appeals to both his gods and the ancestors to intervene.To reinforce his thematic preoccupation, he uses a series of literary devices such as metaphors, symbols, rhetorical questions and repetition. Through rhetorical questions and the metaphorical use of language, we can deduce that the performer is trapped by the fever of nothingness. He senses doom and questions his ancestors for he believes that what is happening is either caused by the negligence of their ancestors or induced by wicked spirits. This is not a normal or natural occurrence in a typical Nso society. This belief brings out an aspect of the Nso custom where it is believed that nothing negative happens without some supernatural forces. Maize is used by the Nso people to produce their staple meal, corn flour which is used for the preparation of corn fufu. The Nso people feel uncomfortable when they go for some time without this important and special meal. Maize becomes a symbol of life and its destruction is a threat to their collective survival. The performer uses the metaphor of maize to decry rampant untimely deaths in his community. He compares maize with children. As maize is central to their well being as individuals and as a community, so are children. He feels empty without maize and laments, “The compound is deserted”.In addition to the corn fufu which is produced from maize is a locally brewed drink known as nkang. This is the most popular drink amongst the Nso people which is used in occasions and ceremonies. The scarcity of maize or the absence of it threatens their unity. The Nso man believes that the philosophy of the truth resides in the cup of nkang. It represents truth; it symbolizes unity and love amongst the Nso denizens.This lamentation is anchored on the philosophy of the Nso community which is communal and not individualistic. The Nso people emphasize the importance of a person to another and when they lose a member or members due to untimely deaths, they are worried. They see the importance of people living together as a community till old age and believe that a “deserted compound” symbolizes emptiness as it threatens their collective existence as a people. This view is shared by other African communities as demonstrated by Uchendu, Okonkwo’s uncle in the conclusion to his prayer in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart when he comments: “An animal rubs its itchy flank against a tree, a man asks his kinsman to scratch him”. (67)Culturally, incantatory poetry helps reveal aspects of the Nso customs and tradition. The Nso people appease the gods or ancestors when their peace is threatened. The oral performer or chief priest calls the ancestors by their names to evoke their spirits to fight those who have offended them and have unleashed calamity on the land. Such people are seen as undesirable elements by the community and the performer who acts as the voice of the people wishes that; “The sun should not rise on him tomorrow.” This is a cursed that has been placed on anyone who has a hand in the mishap.In the incantation performed against drought, the performer shows concern for children because among the Nso people, children are placed at the heart of all agricultural activities. The fact that children will go hungry because, ‘maize is cooking in the dust’ is what has triggered the performance of this incantation regarding the devastating consequences of drought. What this statement by the oral artist means is that drought announces, misery, hunger, diseases, pain, anguish, famine and malnutrition which are serious mishaps in Africa especially in the sub-Saharan region. This situation is a call for concern in the modern society. Therefore, the performance of Nso incantations has relevance in a contemporary context. The people of Nso have a traditional religion that holds the spirit of unity in high esteem. The Nso man believes that one cannot be individualistic in a communalistic society. They share their aspirations, hopes and fears together. That is why in a crisis situation, the chief priests or the family head assumes his responsibilities in order to avert it. It is believed that the deity or ancestral spirit torments heirs or relatives because of the need for their timely and regular performance of the correct rites or sacrifices of propitiation since in their opinion spiritual contamination comes from evil doing, abominable acts, taboos and failure to adopt the right ritual posture. Ancestral spirits that departed in peace are very sensitive to negative acts of disgrace by the living because defilement renders the community vulnerable and susceptible to evil and negative occurrences and requires atonement or purification which is necessary to cleanse the land and appease the ancestors or gods. Prayers chanted and sacrifices offered around shrines are common redressive rites practised among the Nso people to cleanse the effect of spiritual contamination. The performance in this context can also be used as a preventive measure to check any impending evil force from exerting its ugly influence on the community. They feel dejected when their unity is threatened as seen in the incantation performed against new churches in the third poem. The performance of this incantation is anchored on the belief that the proliferation of churches is helping to fragment and disintegrate their families and community in general. Against this background, the performer laments:

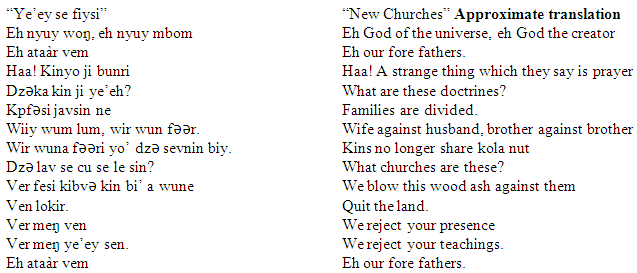

In Nso cosmological system, there is nothing like a natural occurrence. Just as someone can withhold the rain, so too can someone unleash drought on the people with its devastating consequences. It is against this backdrop that the performer during his performance appeals to both his gods and the ancestors to intervene.To reinforce his thematic preoccupation, he uses a series of literary devices such as metaphors, symbols, rhetorical questions and repetition. Through rhetorical questions and the metaphorical use of language, we can deduce that the performer is trapped by the fever of nothingness. He senses doom and questions his ancestors for he believes that what is happening is either caused by the negligence of their ancestors or induced by wicked spirits. This is not a normal or natural occurrence in a typical Nso society. This belief brings out an aspect of the Nso custom where it is believed that nothing negative happens without some supernatural forces. Maize is used by the Nso people to produce their staple meal, corn flour which is used for the preparation of corn fufu. The Nso people feel uncomfortable when they go for some time without this important and special meal. Maize becomes a symbol of life and its destruction is a threat to their collective survival. The performer uses the metaphor of maize to decry rampant untimely deaths in his community. He compares maize with children. As maize is central to their well being as individuals and as a community, so are children. He feels empty without maize and laments, “The compound is deserted”.In addition to the corn fufu which is produced from maize is a locally brewed drink known as nkang. This is the most popular drink amongst the Nso people which is used in occasions and ceremonies. The scarcity of maize or the absence of it threatens their unity. The Nso man believes that the philosophy of the truth resides in the cup of nkang. It represents truth; it symbolizes unity and love amongst the Nso denizens.This lamentation is anchored on the philosophy of the Nso community which is communal and not individualistic. The Nso people emphasize the importance of a person to another and when they lose a member or members due to untimely deaths, they are worried. They see the importance of people living together as a community till old age and believe that a “deserted compound” symbolizes emptiness as it threatens their collective existence as a people. This view is shared by other African communities as demonstrated by Uchendu, Okonkwo’s uncle in the conclusion to his prayer in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart when he comments: “An animal rubs its itchy flank against a tree, a man asks his kinsman to scratch him”. (67)Culturally, incantatory poetry helps reveal aspects of the Nso customs and tradition. The Nso people appease the gods or ancestors when their peace is threatened. The oral performer or chief priest calls the ancestors by their names to evoke their spirits to fight those who have offended them and have unleashed calamity on the land. Such people are seen as undesirable elements by the community and the performer who acts as the voice of the people wishes that; “The sun should not rise on him tomorrow.” This is a cursed that has been placed on anyone who has a hand in the mishap.In the incantation performed against drought, the performer shows concern for children because among the Nso people, children are placed at the heart of all agricultural activities. The fact that children will go hungry because, ‘maize is cooking in the dust’ is what has triggered the performance of this incantation regarding the devastating consequences of drought. What this statement by the oral artist means is that drought announces, misery, hunger, diseases, pain, anguish, famine and malnutrition which are serious mishaps in Africa especially in the sub-Saharan region. This situation is a call for concern in the modern society. Therefore, the performance of Nso incantations has relevance in a contemporary context. The people of Nso have a traditional religion that holds the spirit of unity in high esteem. The Nso man believes that one cannot be individualistic in a communalistic society. They share their aspirations, hopes and fears together. That is why in a crisis situation, the chief priests or the family head assumes his responsibilities in order to avert it. It is believed that the deity or ancestral spirit torments heirs or relatives because of the need for their timely and regular performance of the correct rites or sacrifices of propitiation since in their opinion spiritual contamination comes from evil doing, abominable acts, taboos and failure to adopt the right ritual posture. Ancestral spirits that departed in peace are very sensitive to negative acts of disgrace by the living because defilement renders the community vulnerable and susceptible to evil and negative occurrences and requires atonement or purification which is necessary to cleanse the land and appease the ancestors or gods. Prayers chanted and sacrifices offered around shrines are common redressive rites practised among the Nso people to cleanse the effect of spiritual contamination. The performance in this context can also be used as a preventive measure to check any impending evil force from exerting its ugly influence on the community. They feel dejected when their unity is threatened as seen in the incantation performed against new churches in the third poem. The performance of this incantation is anchored on the belief that the proliferation of churches is helping to fragment and disintegrate their families and community in general. Against this background, the performer laments: The Marxist critic and African prolific writer, Ngugi wa Thiong’o has argued in Homecoming (1972) that Christianity and colonialism are twin brothers and capitalism is their first cousin. If capitalism is the by-product of colonialism and Christianity, then the division and individualism which capitalism breeds are clearly evident in this particular incantation. The Nso society by its very nature is communal and it abhors any individualistic tendencies.This incantation reinforces the social and cultural life of the Nso people. Communalism is an essential aspect of their life. The new churches and their different doctrines have contradicted the communal spirit in that some prevent their members from participating in cultural activities such as death celebrations and commemorations. This has created a shacky cultural atmosphere and foundation because the people believe that when there is no unity their cultural strength is weakened. The Nso people believe that unity is strength; and this strength fosters and enhances development. This performance is relevant to the contemporary context where new churches with new names and new doctrines crop up every day and bring confusion, conflict and frustration to many through their strange beliefs and teachings.The incantations reveal the Nso ecological environment. The material used to appease the gods such as goat, palm wine, palm oil, rat mole, egusi and fowl paint the picture of their natural environment and what it produces. They rear goats and fowls and cultivate maize, egusi and plant raffia palms. They also hunt rat moles for food. This implies that agriculture, hunting and tapping of raffia wine are some of their economic activities. Oral literature thus becomes a mirror through which one can view a society and how man lives and adapts in it. The titles of the poems under reference in this paper, “Untimely Deaths”, “Drought” and “New churches” exemplify the fact that literature is linked to a people’s collective experience and consciousness, and can fully reflect a society both economically, socially, metaphysically, philosophically and culturally.The natural environment of the Nso society has a great significance in the well being of its elements. The different materials used in the performance of these incantations enhance the importance of the physical, metaphysical and ecological environment to a people’s Orature and culture. Orature and culture anchor on nature. The performance of Nso incantations as a tributary of African oral literature offers the Nso elements the education that grows out of their natural environment. The people through these performances are encouraged to rear goats, fowls and cultivate palms and produce palm oil and tap palm wine. They do not only use these items during occasions to offer sacrifices but also sell some and use part as food. Thus, their lives are intricately linked to these elements of their physical environment.The performance of the incantation against new churches reveals kola nut as a symbol of unity among the Nso as the performer regrets: ‘Kins no longer share kola nut’. Kola nut is shared by people with the same aspiration and it is one of the cultural practices in Nso. Jick and Ngam in their already quoted article emphasize the importance of kola nut from the perspective of the Kom tradition when they write: It is important to note here that every old compound in the Kom Fondom has at least a kola nut tree and almost all new compounds today have at least young kola nut trees. … Kola nut is sold throughout Kom and neighboring markets of the Fondom. Consequently, its economic value cannot be ignored. (14)Among the Nso people like the Kom people, kola nut has economic, cultural and social values. It is used to entertain guests. It is shared during sad and happy moments. During burials kola nut is shared. It is also shared and eaten during marriages or any other occasions where people come together in Nso. The Nso people move about with kola nut so as to share with friends on their way. Thus eating and sharing kola nut is one of their cultural practices. It is kept in homes by individuals to entertain visitors and this applies to palm wine. Consequently, kola nut and palm wine are used among the Nso people to maintain cultural continuity since they play a key role in all their social gatherings. The third incantation performed against new churches and their conflicting doctrines focuses on the family. The Nso people are aware that for any community to develop there must be peace, love and understanding among its members. Pessimism always looms in the air when family members disagree. The family is the basic unit and nucleus of any society and when it disagrees, it slows down development in a nation. The nucleus of any nation is the family and husband and wife form the basic economic unit of the economy for they represent the earliest division of labour in human history. Consequently, disagreement between husband and wife must be avoided to ensure peace and development in the community. When a brother stands against a brother just because he belongs to this or that church the community is thrown into chaos. To the Nso man, disunity is a period when kin are denied the opportunity to share kola nut. Such a situation steals their joy and makes them hopeless and unhappy. When kola nut is shared and eaten among the people, information circulates as people eat and comment, share their joy and sorrows and talk about the weather and the issues in the community and the nation as a whole.Through the rhetorical question, ‘What are these doctrines? ‘, the performer who stands on the occasion of the performance as the voice of the entire Nso community shows disgust and rejection. He is taken aback by the way the doctrines of the new churches have gained grounds in the Nso society and how people’s minds have been fragmented. The community is in disarray because of this strange teaching brought by Christianity. The tone in the incantation reveals frustration and confusion among people who are filled with regrets. The rhetorical question further reveals that they are scared of the prevailing situation and desperately need intervention from their gods and ancestors. They invoke the spirit of the gods the Creator of the universe as they denounce the situation. Commenting on the Nso traditional religious practice Augustine Bame Nsamenang in Human Development in Cultural Context: A Third World Perspective contends that: Although God looms so large in Nso life and psychology, the belief is that human beings can only reach him through multiple intermediaries – ancestral spirits and various classes of deities associated with specific mundane objects, places, and phenomena. Hence the ancestor cult - an elaborate set of rituals of homage and supplication developed around ancestors (and deities) rather than around the Supreme Being. The ancestor cult seems to be a universal religious phenomenon: … The ancestor cult prescribes appropriate contacts with ancestors and deities. (90)The argument here is that the Nso people believe in God but to them that God cannot be reached directly except through ancestors. This belief occasions the act of chanting incantations around shrines. They can only have access to the almighty God through their gods and ancestors.Incantations are used by the Nso people to address contemporary issues. There is a vast repertoire of incantations among the Nso people which keeps increasing due to technological developments and new occurrences. New occurrences and new philosophical views that contradict the Nso way of life, especially those that threaten their spirit of oneness as in the “new churches” trigger occasions of performance. The performance brings out the instructive dimension of incantations in the Nso society of old and in the modern one. It creates a channel for the performer who is the voice of his community to express the feelings of the people about events around them. Incantatory poetry among the Nso people serves as artifacts produced by the heritage domain, a resource for local administration, a library for traditionalists and a marketable source of value for cultural entrepreneurs. The Orature of a people transports their history, archaeology and shows how the life ways of the past were made into capital, a shore of authentic knowledge on which political and cultural entrepreneurs could draw. For example, when the performer calls the names of the departed and reminds them: ‘You put me here to head this family’, he reveals himself as the link between the past and present. His wish is for the present to be peaceful. The voice in the poem insinuates regret and fear as he laments: ‘The compound is deserted’. He hopes to lead a life that is as good as that of those who left him “to head this family”. This particular incantation presents the Nso cosmic as a mode of political and cultural organization, a means by which the relics of the past are stored up, reconstructed and revalued.

The Marxist critic and African prolific writer, Ngugi wa Thiong’o has argued in Homecoming (1972) that Christianity and colonialism are twin brothers and capitalism is their first cousin. If capitalism is the by-product of colonialism and Christianity, then the division and individualism which capitalism breeds are clearly evident in this particular incantation. The Nso society by its very nature is communal and it abhors any individualistic tendencies.This incantation reinforces the social and cultural life of the Nso people. Communalism is an essential aspect of their life. The new churches and their different doctrines have contradicted the communal spirit in that some prevent their members from participating in cultural activities such as death celebrations and commemorations. This has created a shacky cultural atmosphere and foundation because the people believe that when there is no unity their cultural strength is weakened. The Nso people believe that unity is strength; and this strength fosters and enhances development. This performance is relevant to the contemporary context where new churches with new names and new doctrines crop up every day and bring confusion, conflict and frustration to many through their strange beliefs and teachings.The incantations reveal the Nso ecological environment. The material used to appease the gods such as goat, palm wine, palm oil, rat mole, egusi and fowl paint the picture of their natural environment and what it produces. They rear goats and fowls and cultivate maize, egusi and plant raffia palms. They also hunt rat moles for food. This implies that agriculture, hunting and tapping of raffia wine are some of their economic activities. Oral literature thus becomes a mirror through which one can view a society and how man lives and adapts in it. The titles of the poems under reference in this paper, “Untimely Deaths”, “Drought” and “New churches” exemplify the fact that literature is linked to a people’s collective experience and consciousness, and can fully reflect a society both economically, socially, metaphysically, philosophically and culturally.The natural environment of the Nso society has a great significance in the well being of its elements. The different materials used in the performance of these incantations enhance the importance of the physical, metaphysical and ecological environment to a people’s Orature and culture. Orature and culture anchor on nature. The performance of Nso incantations as a tributary of African oral literature offers the Nso elements the education that grows out of their natural environment. The people through these performances are encouraged to rear goats, fowls and cultivate palms and produce palm oil and tap palm wine. They do not only use these items during occasions to offer sacrifices but also sell some and use part as food. Thus, their lives are intricately linked to these elements of their physical environment.The performance of the incantation against new churches reveals kola nut as a symbol of unity among the Nso as the performer regrets: ‘Kins no longer share kola nut’. Kola nut is shared by people with the same aspiration and it is one of the cultural practices in Nso. Jick and Ngam in their already quoted article emphasize the importance of kola nut from the perspective of the Kom tradition when they write: It is important to note here that every old compound in the Kom Fondom has at least a kola nut tree and almost all new compounds today have at least young kola nut trees. … Kola nut is sold throughout Kom and neighboring markets of the Fondom. Consequently, its economic value cannot be ignored. (14)Among the Nso people like the Kom people, kola nut has economic, cultural and social values. It is used to entertain guests. It is shared during sad and happy moments. During burials kola nut is shared. It is also shared and eaten during marriages or any other occasions where people come together in Nso. The Nso people move about with kola nut so as to share with friends on their way. Thus eating and sharing kola nut is one of their cultural practices. It is kept in homes by individuals to entertain visitors and this applies to palm wine. Consequently, kola nut and palm wine are used among the Nso people to maintain cultural continuity since they play a key role in all their social gatherings. The third incantation performed against new churches and their conflicting doctrines focuses on the family. The Nso people are aware that for any community to develop there must be peace, love and understanding among its members. Pessimism always looms in the air when family members disagree. The family is the basic unit and nucleus of any society and when it disagrees, it slows down development in a nation. The nucleus of any nation is the family and husband and wife form the basic economic unit of the economy for they represent the earliest division of labour in human history. Consequently, disagreement between husband and wife must be avoided to ensure peace and development in the community. When a brother stands against a brother just because he belongs to this or that church the community is thrown into chaos. To the Nso man, disunity is a period when kin are denied the opportunity to share kola nut. Such a situation steals their joy and makes them hopeless and unhappy. When kola nut is shared and eaten among the people, information circulates as people eat and comment, share their joy and sorrows and talk about the weather and the issues in the community and the nation as a whole.Through the rhetorical question, ‘What are these doctrines? ‘, the performer who stands on the occasion of the performance as the voice of the entire Nso community shows disgust and rejection. He is taken aback by the way the doctrines of the new churches have gained grounds in the Nso society and how people’s minds have been fragmented. The community is in disarray because of this strange teaching brought by Christianity. The tone in the incantation reveals frustration and confusion among people who are filled with regrets. The rhetorical question further reveals that they are scared of the prevailing situation and desperately need intervention from their gods and ancestors. They invoke the spirit of the gods the Creator of the universe as they denounce the situation. Commenting on the Nso traditional religious practice Augustine Bame Nsamenang in Human Development in Cultural Context: A Third World Perspective contends that: Although God looms so large in Nso life and psychology, the belief is that human beings can only reach him through multiple intermediaries – ancestral spirits and various classes of deities associated with specific mundane objects, places, and phenomena. Hence the ancestor cult - an elaborate set of rituals of homage and supplication developed around ancestors (and deities) rather than around the Supreme Being. The ancestor cult seems to be a universal religious phenomenon: … The ancestor cult prescribes appropriate contacts with ancestors and deities. (90)The argument here is that the Nso people believe in God but to them that God cannot be reached directly except through ancestors. This belief occasions the act of chanting incantations around shrines. They can only have access to the almighty God through their gods and ancestors.Incantations are used by the Nso people to address contemporary issues. There is a vast repertoire of incantations among the Nso people which keeps increasing due to technological developments and new occurrences. New occurrences and new philosophical views that contradict the Nso way of life, especially those that threaten their spirit of oneness as in the “new churches” trigger occasions of performance. The performance brings out the instructive dimension of incantations in the Nso society of old and in the modern one. It creates a channel for the performer who is the voice of his community to express the feelings of the people about events around them. Incantatory poetry among the Nso people serves as artifacts produced by the heritage domain, a resource for local administration, a library for traditionalists and a marketable source of value for cultural entrepreneurs. The Orature of a people transports their history, archaeology and shows how the life ways of the past were made into capital, a shore of authentic knowledge on which political and cultural entrepreneurs could draw. For example, when the performer calls the names of the departed and reminds them: ‘You put me here to head this family’, he reveals himself as the link between the past and present. His wish is for the present to be peaceful. The voice in the poem insinuates regret and fear as he laments: ‘The compound is deserted’. He hopes to lead a life that is as good as that of those who left him “to head this family”. This particular incantation presents the Nso cosmic as a mode of political and cultural organization, a means by which the relics of the past are stored up, reconstructed and revalued. 10. Conclusions

- The concluding part of this paper seeks to answer questions posed by the clergy, university lecturers, researchers, educators and evangelists in a Conference held in Mvolyé, Yaoundé from 2nd to 4th September 1975 on the theme “Herméneutique de la litterature orale”. The participants’ principal worry in the conference was whether with the invention of writing, in modern time, the oral literature of different indigenous groups can still play an important role in the development of their communities. They arrived at the conclusion that:“La littérature orale a une fonction importante dans la plupart des sociétés, d’équilibre politique, de prise de conscience soi et dynamisme créateur”. They were of the opinion that: “que l’on travaille plus efficacement à la promotion culturelle, religieuse, ou même économique et sociale de l’homme africain, en reconnaissant et en respectant sa personnalité culturelle fortement marquée jusqu’ ici par l’oralité. (qtd in Jousse, 16)In conclusion, it could be argued that although Nso incantations have their roots in the distant past, they connect with the modern society. They are dynamic and are performed when occasions demand. In other word, they are time-honored performances. They thus provide checks and balances in order to ensure responsible behaviour, morality, the harmonization of society, commitment, hard work and discourage excesses such as dishonesty, laziness and impatience. Due to its elasticity, incantatory poetry in the Nso cosmology can be used to review the past, evaluates the present and anticipates the future In this vein, therefore, this study submits that Nso incantations house Nso culture and connect the present to the past to build a better future thus highlighting the relevance of their religious poetry in a modern setting.In the study of the performance and relevance of Nso incantations in a modern setting, this paper has highlighted the content and functions of three important incantations. They instruct and entertain and it is due to this entertainment that they are brought to the literary market place. During performance, material plucked out of the performer’s mouths is developed into global commodities. It is from this angle that Nso incantations have demonstrated that they provide recreation to their audience at all times. Consequently, these incantations are relevant in the contemporary Nso society where one social event or the other crops up and occasions the performance of oral literature. Numerous untimely deaths, natural disasters like droughts and new and contradictory doctrines as observed in the three poems under reference in this paper are exploited by the oral artist and the community to provide entertainment and instruction. Incantations provide a forum for the promotion of Nso culture and language. The content of the selected incantations introduce the audience to various aspects of the Nso cultural life. They have contributed in the enrichment of the audience’s knowledge of the Nso philosophy, archaeology, history, culture, metaphysics and its natural environment. Through the material used during performance the geography, climate and what it produces is revealed and these help to emphasize the specificity of Nso agricultural practices. The performance preserves the history, geography and philosophical views of the people. In this regards, incantations are a very spontaneous responsive and sensitive art form that cannot only be relevant in the past, but have a lot to do with the present and future. Besides, the present comes from the past and what is relevant in the past cannot ignore, isolate and disconnect itself from the present. In invoking the spirit of the ancestors, the artist metaphorically compares the present to the past in order to build a better future. Therefore, Nso incantations transport important cultural information and knowledge from generation to generation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML