-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2017; 7(4): 117-122

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20170704.03

Referendum as an Institution of Democratization in the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe

Małgorzata Podolak

Faculty of Political Science, Maria Curie Skłodowska University in Lublin, Poland

Correspondence to: Małgorzata Podolak, Faculty of Political Science, Maria Curie Skłodowska University in Lublin, Poland.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The views on the institution of direct democracy have changed during the period of democratic transition. They were referred to, pointing to their various advantages and positive effects, confirmed by the practice of some democratic countries. The referendum is especially treated as the purest form of correlation between the views of society and the decisions of its representatives. The referendum is nowadays becoming more than just a binding or consultative opinion on a legislative act, especially a constitution. First and foremost, it is important to see the extension of the type and scope of issues that are subject to universal suffrage. Apart from the traditional, i.e. constitutional changes, polarizing issues which cause considerable emotion become the subject of the referendum. Problems of this type include, in particular, moral issues, membership in international organizations, or the so-called New Policy. The article presents the role and importance of the referendum institution in shaping the democratic systems of Central and Eastern European countries. The transformation of political systems in Central European states from socialist/communist to democratic ones resulted in increasing interest in the notion of referendum, one of the common forms of direct democracy. The aim of this paper is to analyze referenda in the selected countries of Central and Eastern Europe: Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine.

Keywords: Democracy, Direct Democracy, Referendum, Central and Eastern Europe

Cite this paper: Małgorzata Podolak, Referendum as an Institution of Democratization in the Countries of Central and Eastern Europe, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 117-122. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20170704.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The referendum institution has become a very popular tool in decision-making in Central and Eastern Europe in recent years. It should be noted that in most countries it was relatively rarely used in the years of the communist system. This was mainly due to the lack of appropriate constitutional and legal solutions as well as the specificity of the previous system. The "new democracies" of Central and Eastern Europe have become an interesting topic of research in political science (Puchalska, 2011). One of the methodological reasons is that the political systems in these countries had to start the process of democratization at the same time. The process of building democratic institutions and market economy began (Krouwel, Verbeek, 2001). Nowadays Central and Eastern European countries became the subject of comparative studies, including referendum institutions. The referendum is one of the most popular tools of direct democracy, as citizens thus have the opportunity to participate in the decision-making process (Marczewska-Rytko, 2002). The twentieth century is the time of direct democracy, and therefore the institution of the referendum.Central and Eastern Europe is an area where referendums are frequently held. Anneli Albi argues that it can be called a direct democracy area. The frequency of holding referendums can be partly attributed to the totalitarian past and the newly regained independence, which entails the need to grant the decisions a higher mandate and to glorify the nation as a sovereign (Albi, 2004). The first referendums in Europe after World War II were organized mainly in Western countries, and concerned various issues that voters would decide. Another "wave" of referendum voting took place during the period of political transition in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe in 1990s. The citizens decided on the independence of the state, the privatization, the adoption of the constitution, or the accession to the European Union (Musiał-Karg, 2012). There are decisions made in the referendum which, for various reasons, are of particular importance to a state. In this respect, it is assumed that the subject matter of the vote is a specific case, which does not directly lead to the establishment of the law, but to provide the basis for the competent authorities to make the appropriate decision or other action (Jabłoński, 2001).The main thesis of the article is the view that the institution of the referendum played a significant role in the emergence of states and the formation of their political systems. It is used in decision-making processes related to internal affairs of a state, such as the establishment of a president's institution, the functioning of the parliament, the privatization, the construction of a nuclear power plant, etc.

2. Methodology

- We can accept that the analyzed states will be divided into three groups. The first are the countries in which the referendum institution is used to push for the specific political objectives of its leaders, such as Belarus, Ukraine and Russia. The second group consists of countries where state authorities sporadically refer to referendum: Poland and Czech Republic. The third group consists of countries in which the referendum, apart from the elections, is an important tool of democracy: Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Hungary and Slovakia. Certainly, all these states are far from the level, which is represented by Western countries where there are well-established democracies. The aim of the article is to analyze the political practice in these countries on the basis of constitutional and legal regulations. The research, mainly focused on political practice. The choice of countries is not accidental. They are the countries that share common characteristics:- the communist system was in the states;- there were no constitutional regulations for the organization of the referendum;- the lack of political practice related to referendums;- the lack of civil society;- in the transition period, direct democracy institutions were introduced.Central and Eastern European countries show similarities in terms of political systems, but are culturally, religiously, historically and linguistically diverse. This variation is also due to the susceptibility to the influence of USSR institutions, and to their own path of development.The objectives of the article determined adequate research methods. Firstly, a comparative method was used to demonstrate the differences and similarities in the use of referendum institutions in each country. The use of this method allowed us to determine how often and on which issues referenda are organized. The institutional and legal method was also applied in order to analyze constitutional provisions and referendum bills. This method made it possible to establish that in the legislation of all the states regulations on the referendum can be found.The statistical method proved helpful in determining the frequency and effectiveness of the referendum in each country. This allowed us to say that the Czech Republic is an exception, because there was one referendum in 2003. In other countries referendums are organized, but often, because of low attendance, they are not binding.

3. The Essence of the Referendum

- The etymology of the word "referendum" comes from Latin (referendum - something to be conveyed, referred to; ref ero - to present something for evaluation, to opinion, to inform officially, to answer verbally or in writing). Referendum means turning to a nation as a sovereign for a decision (expression of will) about a specific matter (Olejniczak-Szałowska, 2002). Taking into account that the nation is a collective entity, this decision is made by voting (Czeszejko-Sochacki, 1997). The Latin expression ad referendum signifies that some decisions taken by the representatives must be ratified by the parties represented for full validity (Bouissou, 1976).In the initial period of the formation of representative referendum systems, it was part of the ordinary legislative process without which the resolution adopted by the assembly could not apply. As the role of the representative system grew and expanded, the approval procedure was limited to instances when the resolution of the assembly aroused strong opposition from the public. This procedure was usually initiated at the request of the citizens themselves. Transition of this initiative from citizens to state organs is the moment that decided about the dusk of the referendum as a democratic institution (Zawadzka, 1989).The actual designs for the contemporary construction of the referendum were provided by:1. The Swiss practice of assembly of the inhabitants of the municipality, which in the subsequent stages of the transformations finally took the form of a vote, in which all eligible citizens expressed their will in a particular case (Steiner, 1993);2. On the doctrinal level, the views of Jean Jacques Rousseau, which justified the need and ability to implement the attributes of power directly by a collective sovereign (Jabłoński, 2003).It is not enough for the people once assembled to establish a state system, sanctioning a set of statutes. It is not enough to organize a perpetual government or to make an election of officials once and for all. In addition to the extraordinary assemblies that unforeseen events may require, there should be permanent, periodic meetings that can not be abolished or postponed so that on the appointed day, the people will be called without the need of any other formal convocation (Rousseau, 2002, p. 72).By national referendum, we mean macro-democracy, which could theoretically replace direct democracy. Although there are no known governing systems based solely and even largely on referendum institutions, it can not be denied that from a technical point of view such a way of governance would be possible today. Any citizen entitled to vote could have a computer and by pressing the appropriate key ("yes", "no", "abstaining") they would be able to send their decisions on the issue to the central office of an institution. There is, obviously, a problem to solve - who will formulate questions. Securing the rights of minorities could cause similar difficulties in applying the referendum as a way of governance. There seems to be no other way, apart from dividing the voters into supporters and opponents, and thus transferring without appeal the decision to those who have obtained the absolute majority (Kowalak, 2004).John Naisbitt noted that in today's state of information, people want to personally decide on important matters. More people take part in referendums where they can speak directly in disputable cases, than in the vote for governors. There is not enough trust in the democratically elected representatives, and it is better to speak for yourself in person (Naisbitt, 1984, p. 159).This institution is most often run when the traditional mechanisms of representative democracy fail or are ineffective for specific political or social reasons. It is supposed to be a means of establishing a social agreement, contributing to the easing of political conflicts. It plays an important role in empowering society and shaping political culture (Kiljan, 2001).The referendum becomes more than just a binding or consultative opinion on a legislative act, especially a constitution. First and foremost, it is important to see the extension of the type and scope of issues that are subject to universal suffrage.

4. Motives for Conducting a Referendum

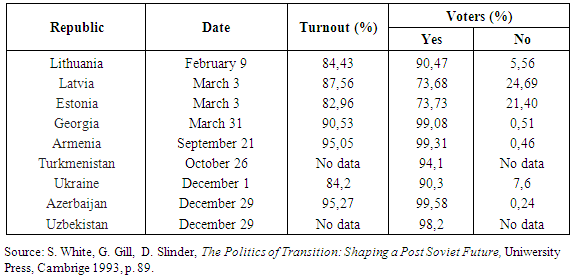

- Motives for referendum are very different. They depend on the experience of the past, as well as the situation of the state, the transformation stage, as well as the functioning of the constitutional organs. He distinguished four distinctive motifs:• deciding on one's own national fate;• legitimization of political power;• systemic constitutionalization;• deciding on systemic disputes (Zieliński, 1997).It should be emphasized that the choice made by participants in the referendum is reduced to an alternative: to accept the whole project or to reject it. They can not therefore bring changes or corrections, and thus influence the shaping of the content of the project. The voting decides on the fate of the project. It is a political act of great importance, but of a specific character. It constitutes the form of allowing or refusing consent to the actions of other ruling groups, representatives. It can be said that the referendum is an intermediate form between the representation system and the direct rule of the people. The decision taken in the referendum can be classified as a form of community control over the actions of representatives, the sovereign control, and not all of their actions, only in specific cases. Referendum is not a typical form of direct exercise of power, because in direct political decision making it should be possible to shape the content of the decision according to the will and the views of the voter (Ciepaj, 1991).Most of the constitutions of the Central and Eastern European countries have a referendum institution (Podolak, 2014). Its place in the decision-making process of the state, the subject of a referendum, types, requirements of validity, etc. have been defined in different ways. However, changes in the basic constitutional principles of the state have been referred to the subject matter of mandatory referendums, organized by law and not at the initiative of a representative body or other authority (Zieliński, 1999).The referendum is decided by the parliament (Poland, Estonia, Hungary) or the head of state (Poland, Slovakia). The following entities have the initiative:- the government (Hungary);- the citizens (Hungary 200,000, Poland 500,000, Lithuania 300,000, Slovakia 350,000);- Members of Parliament (Hungary);- the head of state (Hungary).In the Constitutions provisions have been made for the validity of the referendum. Usually the subject of the referendum can not be laws and freedoms, taxes, military recruitment and state budget (Barański, 2004).Constitutional regulations also provide for the possibility of carrying out so-called constitutional referendum (Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia).In the theoretical dimension we can talk about the developed constitutional structure (model) of the referendum institution, as indicated by the constitutions of many states, which are the subject of analysis. At the same time, it is possible to talk about the limited structure (model) of the referendum institution, occurring as a trace in the text of the constitution, such as the Constitution of the Czech Republic. Not to overestimate the regulation of the constitutional institution of the referendum, we can say that its creation gives some guarantee of appealing to the public and settling of public affairs (Zieliński, 1997).As far as the practice of the above institution is concerned, it should be noted that in Central and Eastern European countries it is used relatively rarely and occasionally but in very important areas.First of all the independence referendums that were held in the former Soviet Union in 1991 should be mentioned. In 1991 the authorities of the republics of Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia, still under the authority of the USSR, called on the public to comment on the restoration of independence. In the polls, the people of Estonia (77%), Lithuania (90%) and Latvia (73%) voted for a return to independent existence and state sovereignty.The Transcaucasian republics of Armenia and Georgia acted in a similar way (Kużelewska, Bartnicki, 2008). Armenia set the issue of its independence, for which 99% of the population opted. Georgia voted to restore independence. In the vote, 99% of citizens voted for independence. The results of the referendums became the legitimacy of proclaiming the independence of the republics.A referendum constituting the question of the independence of the republic was also held in Ukraine. In the 1991 vote, more than 90% of the population voted for independence. This result confirmed the long-term aspirations of Ukraine to state independence. The referendum has become an instrument for expressing the will of the people and for advocating for independence. This form of appeal to the nation proved to be effective in the case of a community with a strong sense of national consciousness and a belief in the need to revive statehood within sovereign states. In all the Baltic States as well as Ukraine, the results of the referendum confirmed the will to live in the national state.

|

5. Discussion

- According to its supporters, the referendum procedure creates the possibility of personal participation in the exercise of power, the impact on the functioning of the state, as well as limitations on the omnipotence of the parliament, in particular in the implementation of the vested interests of certain political groups. It is therefore intended to serve as a sort of "antidote" to the activities of the parliamentary majority, which does not always make decisions in the name of the good of the public. The referendum is the most democratic form of governance, which in its assumption does not intend to resolve conflicts arising between members of the representative bodies, but to give full expression of the will of the sovereign. The very conduct of the referendum is of major importance for the political education of the collective sovereignty and for the creation of civil society (Jabłoński, 1997). The referendum used in this manner becomes a direct democracy institution that values parliamentary democracy and does not oppose this democracy. The use of the referendum brings democratic elements to the decision-making process of creating a new systemic order and enables the realization of the idea of the sovereignty of the nation in direct form (Banaszak, 1999).The opponents of the institution argue differently, claiming that resolving to hold the referendum leads to inconsistencies in the law, and thus undermines respect for representative government. In their opinion, this institution can only be identified with a time-consuming and very costly vote of no confidence referring to the actions of democratically elected representatives. They highlight the lack of social insight on the subject of voting, noting that any suffrage can turn into a peculiar opinion poll, rather than being a substantive solution to an important state problem (Jabłoński, 2003). Political activity and public interest in governance are very limited, adding to the fatigue of voting in areas where they are often carried out. Low voter turnout during referendums is a confirmation of this fact.In order for the referendum to fulfill the function of a school of democratic governance and decision-making, the issues that are to be resolved must be clearly and comprehensibly addressed. It must be preceded by a sufficiently long and comprehensive campaign in which society will have time to get acquainted with various posts. In this way, it is empowered and the opportunities for manipulation that some political forces can reach are diminished.The practice of applying the referendum in the modern world indicates that the way of using it can be very controversial, which is facilitated by a set of objective and subjective shortcomings of this form of direct democracy. The voter is often forced to reduce his opinion to a very high degree, which in combination with the appropriate choice of questions can cause considerable deformation of the will of society. The motives of the voters’ decisions are diverse. Often they are not based on their pool of knowledge and the level of substantive competence. Instead, they occasionally tend to transform into plebiscitary support or refusal of the same for a particular person or persons (Brenner, Höffer, 1996).It seems that in most cases the most appropriate and the most reliable form of referendum is an alternative presentation of several competently prepared variants of the solution. They should also concern a clearly formulated and specific issue. This allows voters not only to express their opinion on a specific proposal, but also to realize what other possibilities are available in the given case. This also helps to some extent to increase the role of substantial motivation in shaping the voters’ decisions. Depending on the subject matter of the referendum and the way in which the questions are formulated, it may, however, become an institution for the verification of expert opinions, social control or supervision (Malinowski, 1996).

6. Conclusions

- In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the referendum institution effectively complements the form of representative government. In the post-communist democracies, the fascination with the general election (presidential and parliamentary) is clearly visible, and it is hard to be surprised since the public has only had a chance to participate in the general election since the early 1990s. The universality and directness of Western European elections is completely different. Western European society is tired and slightly bored by parliamentary democratic mechanisms. The referendum introduces a breath of freshness in legislation. Comparing the interest of citizens to participate in the referendum (measured by turnout) in countries with strong and stable democracies and in the countries that adopt the mechanisms of the democratic state, it is evident that the referendum is more appreciated by those voters who use this institution very rarely (Kużelewska, 2006). The referendum can also engage with representative bodies in shaping social consensus and mitigating social conflicts. Problems arising in the process of systemic reconstruction are difficult to solve in a way that would satisfy different social groups. The majority opting for a particular solution is a factor that allows for unity around specific social values. It fosters the actions of representative bodies and creates a climate of social approval for them (Zieliński, 1997). The referendum institution may not be the future of democracy, but democracy of the future will increasingly refer to the various forms of direct democracy, including the referendum itself. This tendency is now becoming crystallized due to two beliefs pertaining to the essence of democracy. The former shows that the institutions of direct democracy are the protection against over-centralization of the state and the partisocracy – a product of indirect democracy - which leads to the narrowing of areas of freedom and the questioning of the democratic ideal. The latter is that democracy means equality of citizens in both legal and political terms, for whom new forms of implementation still need to be sought.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML