-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2017; 7(4): 99-108

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20170704.01

Socio-Economic Impact of Family Size Preference on Married Couples in Kogi State University Community, Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria

Eboh Alfred1, Akpata Grace Oremeyi2, Owoseni J. S.3

1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Kogi State University, Anyigba, Nigeria

2Department of Sociology, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria

3Department of Sociology, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Eboh Alfred, Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Kogi State University, Anyigba, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

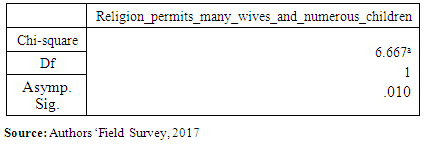

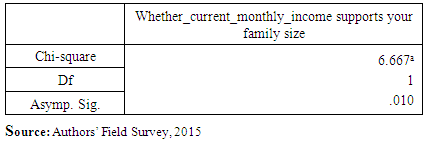

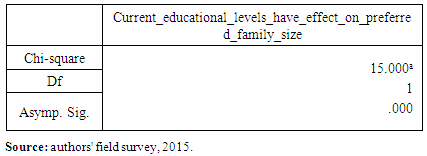

Family size preferences stand as a “silent norm” guiding married couples on the number of children they are expected to bear. Thus, this trend influences the decisions of couples to the extent of having more children than they generally can cater for. This is not without its consequences like decrease in the standard of living, childhood nutritional deficiency, lack of education, increasing crime rate, overcrowding, burglary, prostitution among others. This can grossly add to the excessive population growth in the community with the attendant negative consequences. Against this background, the study investigated the influence of the socio-economic factors on family size preference among the married couples in Kogi State University community, Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria. This study employed a cross-sectional descriptive survey design to investigate 240 married couples using Taro Yamane (1970) and the proportionality formulae to determine the sample size. The semi-structured questionnaire served as the instrument of data collection. The data presentations were made using tables, simple percentages and frequency counts. The hypotheses were tested with the aid of chi-square statistical test at a predetermined 0.05 level of significance as the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17 was used to aid the analysis. Findings showed that religious orientations and beliefs, the current monthly income and educational attainment of the respondents had impact factors on the family size preference. In other words, socio-economic factors of the married couples acting independently or jointly with other variables in the university community could predispose them to opt for a particular family size. The study, therefore, recommended that the university-based religious associations and the various fellowship leaders should enlighten their members and followers on the need to maintain moderate, standard and manageable family size. To this end, incentives including but not limited to affordable school fees and subsidised healthcare services through the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) should be granted to the couples with moderate family size. This could be reinforced by the government in conjunction with the university management organising enlightenment programmes and knowledge-based theatrical shows on the campus in order to promote the culture of standard family size maintenance in consonance with the government policy of a four-child family.

Keywords: Family size, Socio-Economic, Preference and Married Couples

Cite this paper: Eboh Alfred, Akpata Grace Oremeyi, Owoseni J. S., Socio-Economic Impact of Family Size Preference on Married Couples in Kogi State University Community, Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 7 No. 4, 2017, pp. 99-108. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20170704.01.

Article Outline

1. Background to the Study

- It has been noted that the family remains the cornerstone of society. Both in pre-modern and modern societies, the institution of the family has been recognised as the most basic unit of social organisation vested with the responsibility of carrying out certain important tasks like socialisation (Haralambos, Holborn & Heald, 2008). In other words, from simple to complex societies, some traits of the family are likely to subsist even though their nature, patterns and processes might differ markedly (Olutayo & Yusuff, 2012). Family size is an important population, socio-economic and reproductive health issue globally (Hyeladi, Alfred & Gyang, 2014; Arthur, 2005; Sam, Peltzer & Mayer, 2005; Ajao, Ojofeitimi, Adebayo, Fatusi & Afolabi, 2010). While the total fertility rate of various countries varies, low figures predominate in industrialised/developed countries with developing countries/regions of the world witnessing increasing higher growth. Paradoxically, there was a point at which the global total fertility rate fell from 5 children per woman-lifetime in 1950-1955 to 2.7 children in 2000-2005 (Cohen, 2003).Nigeria is the most populous black nation in the world and has experienced high fertility levels over the last three decades, despite the implementation of the national policy on population in 1988 which stipulated four children per woman (James & Isiugo-Abanihe, 2010), with the current fertility rate being 5.7 births per woman which is higher than the average rate recorded for sub-Saharan Africa (5.2) and the average rate recorded across the world (2.7) (Population Reference Bureau, 2005). This might not be unconnected with a high premium being placed on the existence of children either as an asset of labour in an agrarian economy, social symbol or for physical and security purposes (Owumi, Eboh, Owoyemi & Akpata, 2016; Alaba, Olubusoye and Olaomi, 2017). The family which constitutes the primary point (foundation) upon which society is formed (Scott & Gordon, 2006) varies in size and form exists in various notions and is determined by numerous factors, such as cultural (norms and values), socio-economic condition, and political factors. As the major reproductive unit, the family produces new members and their upbringing in the society through socialisation. The capacity of the family to cater for the new members or children is a function of the resources available and accessible (Jennings & Barber, 2013). The status of the new members of society are drawn from that of their family, thus a poor family yields poor children (Sahleyesus, 2005). As a result, this affects the status of the society in general.Furthermore, the number of children noted to be preferred in a society generally influences the population of the society and the population growth rate. To that extent, there is a great need to study and assess the implications of this seemingly “harmless” decision (family size preference) not just at each individual family but also the implications for the university community in question, and the society at large (Adesola, 2012).

2. Statement of the Research Problem

- Family size preferences stand as a "silent norm" guiding married couples on the number of children they are expected to bear. Thus, this trend influences the decisions of couples to the extent of having more children than they generally can cater for. This is not without its consequences like the decrease in the standard of living, childhood nutritional deficiency, lack of education, overcrowding, prostitution, street hawking among others. In Nigerian context, marital fulfilment has a lot to do with childbearing. Studies have shown that marital satisfaction and childbearing have a sort of mutually reinforcing linkage (Owuamanam, 1997; Adesola, 2012). Credence is further lent to the fact that in Africa, most couples desire to have more children probably as a source of honour, wealth and prestige (Thompson, 2001). These trajectories incidentally have some profound implications for family size compositions. Family size is the number of household members comprising children and the head, irrespective of wherever they live (Kamuzora & Mkanta, 2013). The size of the family could be one of the important determinants of the welfare and health of the individual, the family and the community as well as the country (Nigeria) at large (Hyeladi, Alfred & Gyang, 2014). A woman’s family size is said to be the number of children she has at the end of her child-bearing years. In other words, it is her total fertility capacity. The number of children a woman actually does have could be different from the desired number that she would like to have, but for predictive information, this desired number could give a piece of information about the actual number she might finally have (Habiger, 2007; Okolo, N. C & Okolo, C. A., 2013). Family size could be considered large or small, ideal or actual. Depending on the family in question, every family size decision and reproductive health behaviour are naturally laced with some consequences (National Population Commission of Nigeria and Health Policy Project, 2015; Hyeladi, Alfred & Gyang, 2014; Arthur, 2005; Adebayo, 2012; Li, Wi, Dow & Rosero-Bixby, 2014; LeGrand & Mbacke, 2003; Sahleyesus, 2005; Kaur, 2000; Yidana, Ziblim, Azongo, & Abass, 2015). According to Hyeladi, Alfred and Gyang (2014), there is a strong relationship between family size and poverty levels. Large family size has a negative effect on the health of the mothers (Alam, 2012) and household food security (Adebayo, 2012). In terms of children’s access to qualitative basic life-sustaining goods like food, shelter, clothing, healthcare, education among others, family size is largely a determinant factor (Li, Wi, Dow & Rosero-Bixby; Sam, Peltzer, & Mayer, 2005). It has been noted with a disturbing concern by LeGrand and Mbacke (2003) that large family size preference decision and status connects to poverty, deviance and illiteracy. The larger a family is, the more resources it would need for proper upkeep of its members. In other words, having a large family can have negative effects on the health and well-being of both parents and children (Ushie, M.A. Enang, & Ushie, C.A., 2013). Grossly, large family size desirability among a significant number of people has the potency to increase population growth as alluded to by Safdar, Sharif, Hussain and Arasheed (2007). In comparison with smaller families, large families tend to have more closely spaced births with more dependents and less time for a mother to recuperate between births. Consequently, mothers and children of these growing families may be at risk of nutritional deficiency or other negative health outcomes (Wu & Li, 2012; Magvanjav, Undurraga, Eisenberg, Zeng, Dorjgochoo, Leonard, & Godoy, 2013).Furthermore, parents have limited resources to distribute among their children such that the ones available to each child are reduced as family size increases (Sahleyesus, 2005). For example, parents may invest less in a child’s education when they have an unmanageable large family size (Knodel, 1991). Additionally, larger families may “reduce parental emotional investment” in each child (Kidwell, 1981), which can impede social and emotional growth and development. These negative consequences are likely if one or more of the births are unintended (Barber & East, 2009). From the foregoing several research studies conducted on family size preference, it is obvious that desiring large family size is not a celebrated phenomenon in this 21st century Nigeria.The desirability of a large family size is not without the interplay of some underlying key socio-economic factors. Worthy of attention and curiosity is the need to investigate some of these socio-economic determinants of family size preference among married couples. A couple of scholars have noted the impact of income (Yidana et al, 2015), occupation (Li, Wi, Dow & Rosero-Bixby) and religious affiliations (Adesola, 2012; Kinfu, 2000) on rising family size preferences, while others have linked the phenomenon to parental influence (Murphy & Knudsen, 2002). Alaba, Olubusoye and Olaomi (2017) noted a variation in the family size preference among urban and rural dwellers. Also, among many determinant factors influencing family size preference is the educational status of couples (Dibaba & Mitike, 2016; Alaba, Olubusoye & Olaomi, 2017) which has a lot to do with women empowerment towards the use of family planning techniques and family size predisposition (James & Isiugo-Abanihe, 2010). This is further confirmed that the total fertility rate for Nigerian women with no education is about 6.4 and that for women with post-secondary school education is 2.1. The implication is that highly educated women have smaller family size than uneducated ones (Okolo, N. C & Okolo, C. A., 2013). Socio-culturally, religious beliefs and doctrinal practices (Yidan et al, 2015) influence the choice of family size preference among some people. Other factors that jointly or independently influence family size preference among couples include age of husband, age of women at marriage, work status of women and fertility, son preference, geographical location, place of residence, consanguineous marriages, fertility intention (ideal family size), child mortality, polygyny, husband/wife’s desire for more children, wealth index and marital duration (Kamal & Pervaiz, 2011). Factors influencing family size preference have been investigated across several societies. However, there seems to be no single study of such in Kogi State University (KSU) community, Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria. This study is, therefore, designed to investigate the influence of the socio-economic factors on the family size preference among married couples in the university community. The Research QuestionsIn the light of the above, this study is guided by the following pertinent questions to be addressed in due course, namely:1. Do the married couples’ religious beliefs and orientations influence the family size preference in Kogi State University Community, Anyigba?2. What is the effect of the respondents’ income status on the decision to opt for a particular family size in the study area?3. Do the educational levels of the respondents influence their family size preference? Objectives of the StudyThe main objective of the study is to examine the socio-economic factors influencing the adoption of the various family sizes among couples in Kogi State University community, Anyigba. The specific objectives, on the other hand, are to:1. Examine the influence of the respondents’ religious beliefs and orientations in the university community, Anyigba.2. Determine the effect of income of the respondents on the decision to opt for a particular family size in the study area.3. To investigate the relationship between the educational levels of the married couples and the choice of family size in the community. HypothesisIn the course of this research, the following hypotheses were generated and tested in due course.Ho1: the religious beliefs and orientations of the respondents have no significant influence on the kind of family size being preferred in the university community.Ho2: there is no significant effect of the respondents’ monthly income distribution on the family size preference in the study area.Ho3: the educational levels of the respondents have no impact on their family size preference.Conceptual ClarificationsFertility: this refers to the ability of individuals to reproduce themselves in the form of raising children.Fertility Rate: this refers to the actual level of childbearing of an individual or a population.Family Size: this is the total number of children combined with the parent in a nuclear family. In other words, it is the sum total comprising mother, father and children. Family Size Preference: it refers to the family size preferred by people as individuals and community. It varies across societies and levels, with four (4) children constituting the average family size. This is in tandem with the Nigerian population policy of 1988 as adopted in this study.University Community: it is the aggregation of individuals affiliated with the university system who conduct one form of activity or the other within the university's premises. They include the students, academic and non-academic staff, and the campus business operators among others.The Empirical Review on Family Size PreferenceThere have been quite a lot of studies on fertility behaviour and family size determination, including the various variables affecting the upward or downward, large or small, ideal or actual family size preferences among married couples (Arthur 2005; Yidana et al, 2015; Li, Wi, Dow & Rosero-Bixby; Adesola, 2012; Kinfu, 2000). However, findings emanating from some of those studies have been mixed. In line with the objectives of these current study, the following studies are hereby teased out and reviewed empirically.Dibaba and Mitike (2016) conducted a study titled “Factors Influencing Desired Family Size among Residents of Assela Town”. The study adopted a community-based cross-sectional research design spanning between March 25 and April 4, 2013. A total of 428 residents were included in the study. The age of women ranged from 15 to 49 years and men above 15 years. The desired family size was determined using mean score. Respondents were asked to determine which factors were influential on their desired family size. Descriptive analysis, 95% CI and multiple linear regressions were used to investigate the relationship between the independent variables and desired family size. After recording the variables, logistic regression was used to see the association between family size preference and predictor. Among the major findings, it was discovered that women belonging to Protestant and Catholic religious groups had relatively lower mean desired family size when compared to those following orthodox Christian and Muslim. Also, respondents who had primary education desired higher family size than those who had more than secondary education. The study concluded that it was quite possible that increasing educational level and age at marriage might influence couples to desire lower family size. Educational level and knowledge of family planning affected family size preferences. Similarly, James and Isiugo-Abanihe (2010) carried out a study to examine Adolescents’ Reproductive Motivations and Family Size Preferences in North-Western Nigeria. A community-based and cross-sectional research design was adopted. Primary data were obtained using quantitative methods. A survey of 1,175 adolescents aged 12-19 years was carried out, using multi-stage sampling techniques involving States, Local Government Areas (LGAs), towns/villages, main streets, houses, households and individuals. Frequency distribution, multiple classifications, chi-square, and regression analyses were used for data analysis. The results of the current study show that gender, residence, ethnic origin, religion, educational level, knowledge and approval of contraceptive methods were significantly associated with family size preferences (p<0.05)The link between religious orientations and fertility behaviour has been explored in another study conducted to determine the socio-cultural and economic factors underscoring family size preference among the Obstetric population in Orlu South East Nigeria by Egenti, Chineke, Merenu, Egwuatu, and Adogu (2016). The study utilised the cross-sectional descriptive study in which systematic sampling technique was used in selecting the respondents. Data were collected using both self and interviewer-administered questionnaires and analysed with the aid of standard statistical method. The major findings showed that not much variation exists in the family size preferences among the major religious faiths of Catholic, Anglican and Pentecostal. However, the study showed that 3 (50%) of adherents of Islamic and Traditional religions said they desired to have 7 children and above. The Roman Catholic respondents showed the least contraceptive usage while those who attained tertiary education desired fewer children than those with primary and secondary educational levels. Unemployed respondents and civil servants preferred to have 0-3 children on the average. Marital status, place of residence and use of contraception were the other factors that had significant influences on family size preference (p<0.01, p<0.001 and p<0.000 respectively). The conclusion drawn from the study was that socio-cultural and economic factors were important determinants of family size in Orlu, South East Nigeria.Similarly, Ojo and Adesina (2014) investigated in a study titled “Women Empowerment and Fertility Management in Nigeria: A Study of Lafia Area of Nasarawa State. Two hundred women of working age married were selected in the study area. The selection of the 200 respondents was done using the stratified random sampling technique, to ensure the representativeness of the sample, and this covered the political wards that constitute the study area. One hundred and eighty-four (184) copies of the questionnaire out of the two hundred sent out were returned and treated for the analysis. The coefficient contingency and the chi-square (X2) techniques were employed. The findings show that the level of women’s education, women’s employment status and women’s level of income, influences them to adopt small family size. The study concludes that fertility management is a very potent tool for women empowerment and vice versa. The study concluded that there existed a positive relationship between the women’s level of income and their preference to adopt small family size. Women's levels of income have a central role to play in determining fertility management among women. When women are empowered through education, capacity enhancement, more skills, high income, more opportunities and options in the superstructure they will voluntarily reduce their fertility.According to Okolo, N.C and Okolo, C. A. (2013), education and income are variables influencing family size preference amongst female health professionals in Uduth Sokoto. The authors used a cross-sectional descriptive survey design with the population participants made up of female health professionals working in UDUTH. There were two hundred and thirty-four (234) female health professionals working in UDUTH comprising doctors (10), pharmacist (2), laboratory scientist (8) and Nurses (214). The instrument for data collection was a self-administered questionnaire while the data were analysed manually using appropriate statistical methods with the level of significance at ≥0.05. The major findings showed that A total of 29 (16.1%) of respondents choose religion as the determinant of their family size decision. Since it is known that Islam allows for a large family size, and most of the respondents are Muslims, yet the percentage is low; this goes to show that, even though religion is a factor, it is not so much a major factor to determine family size among educated women. Only 42 (23.3%) of the respondents indicated that their educational background had contributed to the choice of their desired family size. One would have expected that educational background would have played a greater role in the decision of these women to have a particular family size. These health professional are aware of the risks and problems associated with a large family size and so are supposed to be educationally primed but from this study, 76.7% did not agree that their educational background had an influence on their family size decision.

3. The Methodology

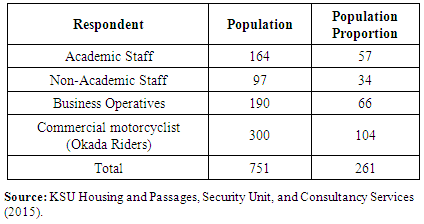

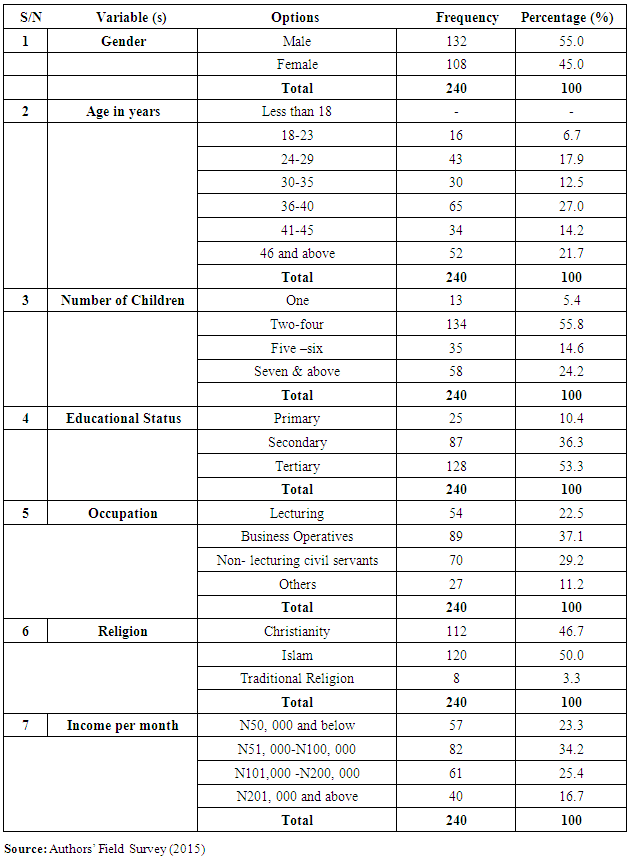

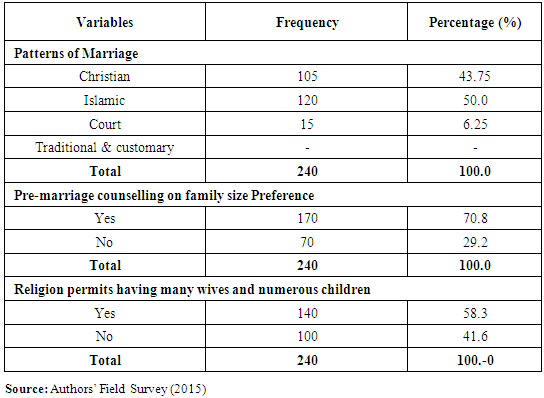

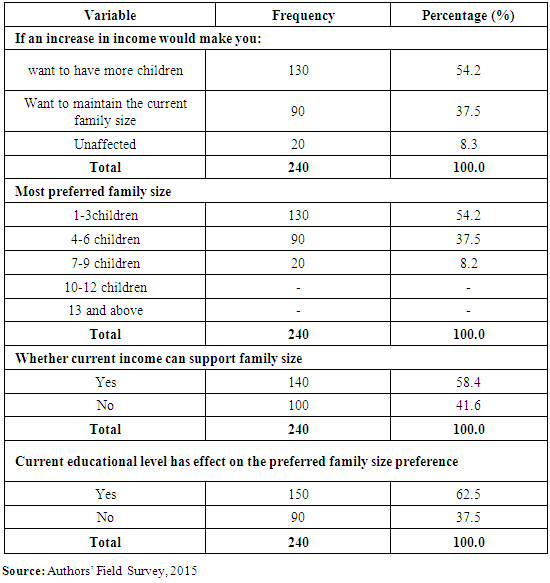

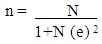

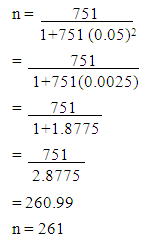

- This study employed cross-sectional descriptive survey design, which was used in studies spanning a short period of time and assesses the prevalence of the outcome of interests, for the subgroup within the population.The Study Area/Population The study was conducted in Kogi State University Community, Anyigba. Anyigba town is the eastern flank under Dekina Local Government Area of Kogi State. Parts of the university community covered by the research include the academic staff, non-academic staff, business operatives, motorcycle riders and others. The study thus excludes single and unmarried subjects, university staff resident outside the school quarters from the survey. The population of the study includes the academic staff resident in the university quarters numbering 164; the non-academic staff numbering 97; the business operatives numbering 190; and the Okada riders numbering 300 (KSU Housing and Passages, Security Unit, and Consultancy Services, 2015). Thus a total of 751 research subjects. Sample size and Sampling TechniquesThe study made use of a sample of 261 married couples as respondents. This was determined using Taro Yamane formula (1970). This time-tested formula is:

Where:n = sample;N = Population size;e = Degree of tolerance error;with a significance level put at 95%, the degree of error term will be 5% (i.e. 0.05).Therefore:

Where:n = sample;N = Population size;e = Degree of tolerance error;with a significance level put at 95%, the degree of error term will be 5% (i.e. 0.05).Therefore:  Sample size = 261.To further ensure representative sample size distribution, the study utilised the proportional sampling method with the aid of the proportionality formula thus:Q = (A/N) n/1. Where:Q = the number of the questionnaire to be allocated to each segment.A = the proportion of each segment.N = the total population of all the segments.n = the estimated sample size used in the study.

Sample size = 261.To further ensure representative sample size distribution, the study utilised the proportional sampling method with the aid of the proportionality formula thus:Q = (A/N) n/1. Where:Q = the number of the questionnaire to be allocated to each segment.A = the proportion of each segment.N = the total population of all the segments.n = the estimated sample size used in the study.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The main objective of the study is to examine the factors influencing the adoption of various family sizes among the married couples in Kogi State University community, Anyigba. When other factors like son preference, age of women, age of husband, age of women at marriage, work status of women and fertility, region of residence, place of residence, consanguineous marriages, fertility intention (Ideal family Size), child mortality, polygyny, husband/wife's desire for more children, wealth index and marital duration are held constant, the trio, namely: religious beliefs and orientations, the current monthly income and educational attainment of the respondents had impact factor on the family size preference. In other words, socio-economic factors of the married couples acting independently or jointly with other variables in the university community could predispose them to opt for a particular family size. In view of the findings emanating from this study, the university-based religious associations and the various fellowship leaders should intensify their education on the need to maintain moderate, standard and manageable family size. This is regardless of gender preference in the family. Furthermore, the knowledge of the national population policy is vital for attaining the standard family size of 4 children. To this end, incentives including but not limited to affordable school fees and subsidised healthcare services through the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) should be granted to the couples with moderate family size. This could be reinforced by the government in conjunction with the university management organising enlightenment programmes and knowledge-based theatrical shows on the campus in order to promote the culture of standard family size maintenance in consonance with the government policy of a four-child family.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML