-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2017; 7(1): 39-44

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20170701.06

Inclusive Education: Determinants of Schooling in Urban Slums of Islamabad, Pakistan

Usman Sattar, Dunfu Zhang

School of Sociology and Political Science, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China

Correspondence to: Dunfu Zhang, School of Sociology and Political Science, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper seeks to identify the factors determining school enrollment in slum localities of Islamabad, Pakistan. A quantitative research design with the survey method was adopted to obtain data from household heads. The sample was consisted of 220 respondents. The data was collected with convenient sampling technique. A structured questionnaire was prepared as a tool for data collection. The data was analyzed with logistic regression model on STATA 0.9 software. The results disclosed that child’s gender, household income and household head’s education are important factors determining school enrollment in slum localities of Islamabad, Pakistan.

Keywords: Children Education, Gender, Poverty, Slums, School Enrollment, Pakistan

Cite this paper: Usman Sattar, Dunfu Zhang, Inclusive Education: Determinants of Schooling in Urban Slums of Islamabad, Pakistan, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 39-44. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20170701.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

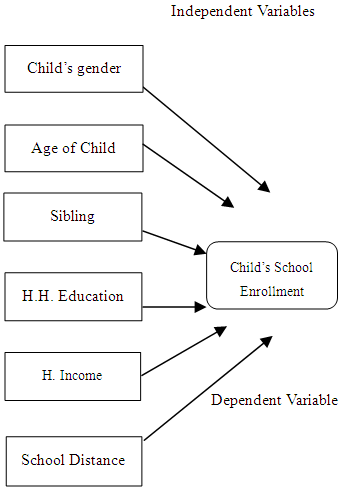

- It is evident in the literature that 100 % school enrollment is still challenging for many developing countries though providing free educational opportunities to impoverished communities [1]. However, few people among them, although having similar underprivileged lifestyle e.g. lack of healthy nutrition, clean clothing, social security etc. yet they send their children in school (inclusive education). They realize the possibility that education can play vital role in turning their marginalized living to a prosperous and productive resource at larger level. It is most probably that countries with high literacy rate are more frequent in handling challenges in the process of development as compare to countries with low literacy rate. It strengthens economies, political structures and enables people for sustainable growth and overall societal development. United Nations is still in progress to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (sustainable development goal 4).Universal primary education schemes failed to achieve 100% participation of children in schools worldwide by 2015. It shows still there is missing something to cope with such gap. Literature shows many factors behind such failure however keeping aside those issues, this study focuses on those circumstances which contribute to lightening the lamp (formal education) in the darkness (backward communities). [2] found that household characteristics matters a lot in determining schooling decisions made by household heads. These characteristics involve household economic condi-tions, parental education, gender, sibling, location of household, heath problems, cultural factors etc. The situation is alarming at more backward and remote localities of urban areas where huge population of nomads live without basic infrastructure. They are usually unable to meet their daily needs such as food, shelter, sanitation systems etc. and such vulnerable communities are defined as slums. Here people live in tent houses and their main enterprise is house to house garbage collection. They collect glass, board, plastic etc. and sell it for their livelihood. They usually engage their children in garbage collection that reduce their chances to be enrolled at school. Such communities are also part of federal capital of Pakistan, Islamabad.According to Population Census 1998 of Pakistan, there were total nine slum areas with different number of habitants in Islamabad. These slums include Sumbal Korak, Dheri Qila, Sector, F-7/4, G-7/1, F-6/2, G-7/2, I-11, and G-8/1. The total population of these slums at that time was 34412. All these slums were located in urban settings on the bank of nulls in different sectors of the city. Capital Development Authority (CDA) has tried to shift these slums outside of urban settings many times but failed. However, limited success in case of demolishing I-11 slums in August 2015 (Dawn News Islamabad). Earlier, CDA established a colony namely Farash Town for slum dwellers but they sold out their plots and returned back to slums at variably same locations of urban areas in the city.It was hypothetically due to their enterprise and transport issues that they did not get settled in Govt. approved colonies. Most of them historically migrated from rural to urban localities for their better living. However, some of them who planned it well according to future requirements, successfully started their enterprise and became temporarily settled but due to lack of awareness about changing environment significant people fail to meet their future needs as [3] highlights that uncertainty and urban life pressures of urban areas exhaust people in Asia but they can’t escape. Resultantly, those who had an option to go back, they probably moved and others built up tent houses in city area. Such migrants mostly referred to as less educated, might therefore, they were being exploited as laborers with minimal remuneration and thus compelled to live in slums. Their dreams mostly become illusionary and immense suffering makes them very disappointed. Most of them were failed to enroll their children in schools due to many reasons. But, at the same time, there were few people living in these areas who sent their children in school.This study focuses to identify household characteristics of school going children aged 5-14 living in slum localities of Islamabad. Although there were many factors that might be considered as a barrier in the way of children’s education but particularly those encountered with more backward slum people, is the whole concern here. The relationship of many household socio-economic factors with children education has been examined in this study. This is first study of its type focusing on child enrollment from slum localities of Islamabad. It would help to many international and local ongoing projects on education to make sure school participation from impoverished communities. It is evident that Universal Primary Education (UPE) under the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and local Free Primary Education (FPE) schemes by Govt. and Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) did not achieve 100% enrollment rate. It is hypothetically because of overestimating the needs of the people.This study has highlighted household’s social, economic and demographic characteristics that lead to child enrollment in schools from slum people which may lead to policy arrangements and field operations to mobilize slum household heads to send their children in schools which enclose great sociological significance for sustainable development. The study has focused on the question that how child’s enroll-ment status changes with changing household heads’ income, education, and child’s characteristics such as gender and siblings; and how locality of slum has an impact on school enrollment? Keeping in view the research questions, the objective of this study was to identify the factors contributing to such a pro-poor push to school by slum children.

2. Literature Review

- [4, 5] developed household production function approach which has often been used by researchers in economics and sociology of education to show that household characteristics such as levels of parental education and income determine whether a child enrolls in school or not. Such predictors were strongly attributed with schooling of children and have largely been used to understand children’s educational attainment.[6] examined the factors that prevent slum children gaining access to schooling in the light of urban poverty and rural urban migration. The results demonstrated a bias against gender and caste. [7] identified that those parents who live in slum areas had less motivation for their children’s schooling as compare to those who live in non-slum areas. [8] reported in Kenyan slums that a child’s access to schooling diminishes as he or she ages. The study further revealed that major cause of such situation was household poor financial conditions. [9] found that the education of boys was linked with fathers’ education and the education of girls with mothers’ education.[10] identified that children’s educational attainment has mainly been associated with parental education levels and with the household socio-economic profile. They further found that gender bias in schooling decisions still present. [11] explored that income and socio-economic status of a household, including its educational status have for long time been known to be a consistent predictor of children’s educational attainment. [12] indicated that the value of education was equally important for both girls and boys among Muslim slum dwellers. However low-income had its effects on literacy rate among Muslim dwellers in Kolkata. [13] concluded that child’s age and household income are significant indicators of schooling, gender of the child is important in rural areas; girls have lower enrollment than boys.[14] have given recommendations to facilitate schooling attainment to underprivileged children living in slum localities. [15] indicated that factors such as awareness building and involvement of parents in their children’s education were also crucial. [16] identified interlinks among the lack of education, deprivation, poverty, low income levels, and caste and gender divides in society.[17] has argued that the urban poor might be denied access to basic services because they lack political clout. Although many attempts have been made to understand the reasons behind low school enrollment in many developing countries but less work is done to specifically highlight the low school enrollment in slum localities where people face severe kind of deprivations. These are poorest of the poor who lack basic needs and are mostly neglected by the Govt. agencies. A further study was needed to understand the household characteristics of slum children and try to make sure their participation in schools through some policy arrangements. The present study is first of its type examining the problems of schooling in slum localities of Islamabad. A recent study conducted by the author identified research gap stating that as developing countries undergo rapid urbanization, further research on the schooling of slum children is required. The research gap on particular issue has also been highlighted by many other international researchers. For example, in India, where the populations of the slums account for nearly a quarter of the total population in metropolitan cities, the limited number of previous ad hoc attempts at slum studies has not been able to successfully examine children’s education. Therefore, the indicators of schooling for slum children are still under-researched [6].Therefore, it is evident in the literature that many social, economic and demographic factors have been causing low school enrollment but less is known that how to make sure 100% school enrollment. Many researchers have shown the importance to focus on poorest people in society others felt parental education as important determinant for schooling of children. In addition, this study has also focused household head’s education hypothesizing as an important indicator for children’s schooling as they own power to make schooling decisions as well.

| Figure 1. Conceptual Framework |

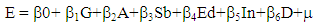

| (1) |

|

3. Methods

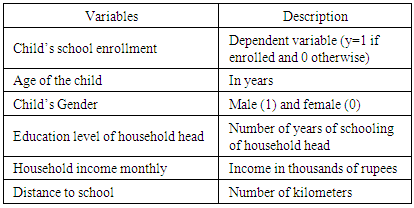

- A quantitative research design was chosen due to quantitative nature of variables selected for the present study. The targeted population was the households with children of school going age (5-14) living in slum areas of Islamabad, Pakistan. A convenient sampling technique was used in this study as a complete and updated list of households (Sampling frame) was not available to any agency in the country. The sample size was limited to 220 households conveniently obtained from different slum localities. The nature of this study required field visits in each slum therefore survey method was used for data collection. The respondents were household heads. A structured questionnaire was developed as a tool for data collection. In order to validate the tool, 20 responses were collected from different sectors.The data was analyzed on statistical software STATA 0.9 and the process has been given here. The responses were coded by mathematical numbers for statistical purposes to check the relationship between independent and dependent variables. Two variables were coded in categorical form. The first was dependent variable (child enrollment) and second Independent variable (child’s gender). All other variables were measured in quantitative form. The variables were automatically decoded on main windows of STATA.The data was inserted in columns represented dependent and independent variables on STATA data editor. The respondents were numbered in rows on the same sheet. The data editor was closed after putting all responses. All responses were automatically converted in variable forms on STATA main window. The theory underlying the model was that child’s school enrollment was attributed with household characteristics. The present study contained one dependent variable which was qualitative in nature and presented in categorical form. There were six independent variables which were both quantitative and qualitative in nature. A multiple logistic regression model was used to check the relationship between independent and dependent. variables as it allows simultaneous comparison of more than one variable [14].

4. Results

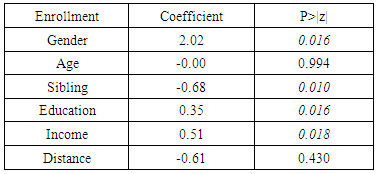

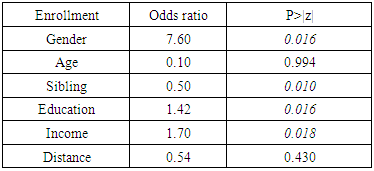

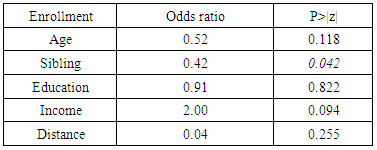

- The results were generated by statistical software STATA 0.9 and the detail of results has been presented in this section. The results have been explained in three different sections. The first section explained results of both genders and schooling, second described only male children and schooling and third showed only female children and schooling. Hence, the conclusion of following results has been given at the end of this chapter.Section 1 Both Genders The results were on the basis of 220 observations taken from slum household heads. The value of R square is 0.59.

|

|

|

|

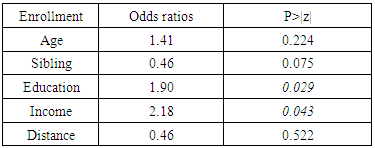

5. Conclusions and Further Discussions

- The overall results concluded that one kilometer increase in distance of nearest school and one-year increase in age, negatively affected child’s school enrolment 46% and 1% respectively. Similar results were found earlier but they were not significant indicators determining schooling in slum localities of Islamabad. It showed that if financial position of household head is good with some schooling experience, they were more likely to send their children in schools regardless of age of the child and distance of the nearest school.Sibling has turned not to be significant factor for predicting school enrollment of children in slum areas of Islamabad. It was persistently affecting both male and female children collectively as well as individually. The education of the household head and the income of the household were also significant determinants of schooling when taken together. However, on individual level, these factors were significant predictors of school enrollment for male children and insignificant for female children in slum areas of Islamabad, Pakistan.This study was limited to slum areas of Islamabad only. Further, this study represented limited explanations of response variable and more research is needed to assess the reasons behind low school enrollment of slum children. A comprehensive case study on slum people is needed to explain their culture and mind sets with regard to schooling of their children and which factors reduce the chances of female education even as the education of household head increases, which could be further addition to this area of investigation.The study did not focus on other important variables such as cultural factors and difference of school enrollment among legal and illegal slums, Christian and Muslim slums which can be focused further.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML