-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2017; 7(1): 33-38

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20170701.05

Gender Biases Against Women in Labor Division in Kenya’s Ministry of Education

Solomon Wachara Omer1, Pamela Raburu2, Jack Ajowi2

1Faculty of Education Foundations, St Agustine University of Tanzania, Mwanza, Tanzania

2School of Education, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology, Bondo, Kenya

Correspondence to: Solomon Wachara Omer, Faculty of Education Foundations, St Agustine University of Tanzania, Mwanza, Tanzania.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The study invstigated gender biases against women in labor division in Kenya’s Ministry of Education. The research study was guided by the African feminism as a theoretical frame work. The concurrent triangulation design, which is one of the Mixed Methods Approach models, was used in the current study. The target population in this study consisted of the thirty six Sub-County Education officers in the six sub-counties of Kisumu county. These are the six Sub County Directors of Education (SCDEOs), the six Quality Assurance and Standards officers (SCQASOs), the six Deputy Assitant Directors (Teacher Management), the six Sub-County Examinations Officers (SCXO). In view of the number of Education officers in the six Sub-Counties of Kisumu county, the current study employed saturated sampling technique. Thus, all respondents were given opportunity to participate in the study. The main Instruments of data collection in this research were the questionnaires, interview schedules and document analysis guide.In order to ensure this, the researcher sought the expert judgement from lecturers in Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST). The split-half method was used to ascertain the reliability of the questionnaires. In this research study, the correlation coefficient was 0.845 and thus was considered appropriate. The results show that the multiplicity roles that women play in the domestic, productive and reproductive spheres which the labor policy seem not to recognize, limit women’s capabilities to seek top management positions. The study recommended that The Ministry of Education should strive to put in place and affect the policy that will ensure gender equality and equity in the recruitment and promotion of education officers in top management positions.

Keywords: Gender biases, Women, Labor division, Kenya, Ministry of Education

Cite this paper: Solomon Wachara Omer, Pamela Raburu, Jack Ajowi, Gender Biases Against Women in Labor Division in Kenya’s Ministry of Education, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 33-38. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20170701.05.

1. Introduction

- Societies worldwide at different times and different geographical locations have never been egalitarian. An egalitarian society where all men are equal and no one will experience the indignity of being relegated to a lowly position is yet to be found [1]. All human societies have some forms of social inequalities because power, prestige, social status, wealth and other resources are unequally distributed between individuals, groups and societies. The study revealed that one of the major social inequalities that has been sustained from time immemorial is gender inequality, which is the male domination of women in the society. The foundation of modern education in Kenya was laid by Christian Missionaries who introduced writing and reading to spread Christianity, and throughout the colonial period, women in Kenya experienced considerable social, economic and political inequalities relative to men. The state favoured males in the provision of paid labour needed by settler economies, thus, resulting into women being grossly underrepresented in paid labour but served as unskilled labour in the agricultural sector [2]. Another related study [3] showed that 33.3 percent and 32.1 percent of top and middle management positions respectively were held by women. In terms of professional qualifications, 55 percent and 51.5 percent of M.Ed. and B.Ed. holders respectively, were women. Both male and female genders were rated ‘high’ in possession of skills and personality characteristics the respondents considered important for top educational management and leadership positions. This view received support [4] that the barriers which retard women’s progress in management include the endocentric bias and partriachal nature of the society, the traditional stereotypical perceptions of women’s abilitites and attitudes towards women’s family roles which makes it difficult for women to be accepted as managers. The national gender policy in Zimbabwe [5], states that a gender just society in which men and women enjoy equity, contribute and benefit as equal partners in the development of the country.Although there has been significant shifts in terms of policies and legislations on gender equity, government often lack the financial resources and political will to implement them and the progress is slow [6]. In the Republic of Kenya, the new constitution that was promulgated on 27th August, 2010 has far reaching provisions that will enable gender equality and freedom threshold. The guiding principle here is that the achievement of gender equality, equity and women’s empowerment are accepted development goals and essential planks for Kenya to become a developed country by 2030. The Kenya National Commission for Human Rights [7] reported that although the discriminatory laws have been addressed in Kenya’s New Constitution, women still face many challenges in regard to accessing top management and leadership positions. From the fore going, the studies point to the fact that women are under-represented in the top management positions in higher education due to the societal cultural view of women as a group and or individuals.The research study was guided by the African feminism as a theoretical frame work developed by African scholars [8-12], who argued that, African Feminism is opposed to how Western Feminism dichotomises human relations by placing males against females, as well as the individualism and competitiveness which is dentrimental to the African female course. Gender bias against women therefore shows that while male adult literacy is the highest, female adult literacy is lower. This means that inadequacy in educational preparedness for the females results in their under employment or end up in informal sector with little or no opportunity for advancement; [1, 14]. A research study [15] established that women do experience a strong gender bias when being evaluated for promotions on both their level of performance as well as their potential impact. Furthermore, [16] it is argued that although it is widely acknowledged that educational attainment has the potential to equalize the distribution of employment and earnings, empirical evidence in Kenya has mainly focused on monetary return to educational attainment. International Labor Organization [17] confirms that in Kenya, employment is governed by the general law of contract, as much as by the principles of common law. According to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [18], the employment rate of prime-age women in 2005 was 10% to 20% smaller than that of their male counterpart in most Organizations for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Smaller gaps are found only in the Nordic countries, with Finland being the country with the smallest gap (6%). The gender employment gap is highest in Turkey, Mexico, Greece, Korea and Italy. The gap is still well above 30%, and therefore, these countries still lag dramatically behind the OECD average (20.6%). Thus the practice of glass ceiling worldwide prevent large number of women and ethnic minorities from obtaining and securing the most powerful positions in higher grossing jobs in the workforce regardless of their qualifications and achievements [19].Studies done in Kenya [20-27] have largely concentrated on women under representation in the Higher Education leadership and or career advancement, leaving out women’s promotion to top management in educational system. Thus, there is not much research about gender biases against women in labor division in Kenya’s Ministry of Education. The present study therefore investigated gender biases against women in labor division in Kenya’s Ministry of Education.

2. Research Methodology

- The concurrent triangulation design, which is one of the Mixed Methods Approach models, was used in the current study [28]. Accordingly, this model is selected when the researcher uses two different methods in an attempt to confirm, cross-validate or corroborate findings within a single study. The research design employed both qualitative (interview and open-ended questions) and quantitative (questionnaires) to collect data from the respondents. The target population in this study consisted of the thirty six Sub-County Education officers in the six sub-counties of Kisumu county. These are the six Sub County Directors of Education (SCDEOs), the six Quality Assurance and Standards officers (SCQASOs), the six Deputy Assitant Directors (Teacher Management), the six Sub-County Examinations Officers (SCXO), to whom the questionnaire was administered and the six senior Sub-County officers from the Kisumu County Director of Education’s Office, who were interviewed by the researcher on the day and time that was agreed upon. Thus, they were to form a total 42 education officers/participants in the research study.The current study employed saturated sampling technique. Thus, all respondents were given opportunity to participate in the study. The main Instruments of data collection in this research were the questionnaires, interview schedules and document analysis guide [29]. In order to ensure this, the researcher sought the expert judgement from lecturers in Jaramogi Oginga Odinga University of Science and Technology (JOOUST). The split-half method was used to ascertain the reliability of the questionnaires and a correlation coefficient of 0.845 was reported. Descriptive statistics was used in data analysis which entails the use of frequency distribution tables and percentages to summarize data on the closed-ended items in the questionnaire [30]. The current research study employed the thematic analysis approach which was found relevant due to its importance in giving personal feelings from the respondents.

3. Findings & Discussion

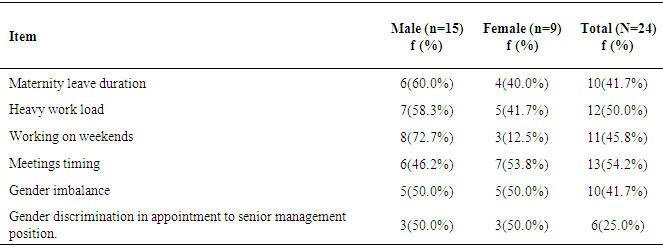

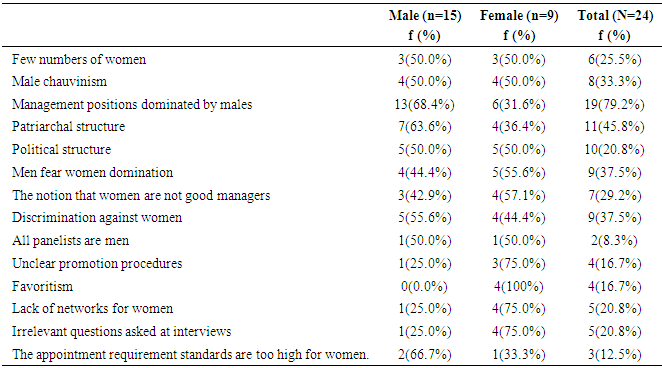

- The study established the existence of any gender biases in labor divisions in Kenya’s Ministry of Education. The researcher developed two sets of statements to examine this construct. The items were designed in such a manner that they were linked to gender biases in labour divisions in the Ministry of Education which were associated to obstacles to women in accessing top management positions. The statements were put in two different sub-headings; the labour policies that are insensitive to women managers’ multiple roles and the ministerial reasons that explain the absence of women managers. The respondents were asked to tick the appropriate response in each case given their perception on the statement in regard to women opportunity at top management positions. From the responses, the researcher computed percentage frequencies of the responses. Table 1 presents the summary of the responses on the labour policies in the Ministry of Education that are insensitive to women managers’ multiple roles.

|

|

4. Conclusions

- The study concludes that, labor policy of gender equality, equity and women empowerment which are also enshrined within development goals and Kenyan’s own development strategies are yet to be achieved fully in Kisumu county as well as the entire country. Thus, the organizational culture to include a democratic process of appointing the leaders based on one’s qualification and achievements rather than those other factors like political correctness, patronage and personal relationships. It is incumbent upon the Ministry of Education to notice that the appointment process, stereotypical tasks and nomination of top leadership which is male friendly lowers the women’s self-confidence and career aspirations. The study recommends that the Ministry of Gender to sensitize the society to recognise the significance of women’s contribution and allow them meaningful participation in developement and decision making process at the top managerial position and foster equitable sharing of profits.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML