Rana Wadi, Raffaello Furlan

College of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, State of Qatar

Correspondence to: Raffaello Furlan, College of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, State of Qatar.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

During the second half of the 20th century Qatar has beheld its first urbanization period, which was caused by the increase of oil’s production. At present, national development strategies have led to an extensive urban transformation process. The rapid urban growth of Qatar presents a challenge to policy makers and planners for involving environmental-behavior researchers in the process. Namely, studies focusing on the ‘Quality of Urban Life’ (QOUL) provide such opportunities by analyzing the settings and people’s satisfaction of existing neighborhoods. The aim of this research study is to assess the QOUL of neighbourhoods in Qatar through an analysis of the built environment and residents’ satisfaction. Namely, QOUL of New-Salata’s neighborhood in Doha was explored through residents’ perception of the (A) physical environment, (B) the social and (C) perceptual factor. The relevant data was collected through site visits, field observation, walk through assessments and in-depth interviews with residents. The findings reveal that (1) residents spend most of their spare-time in the public park and/or sport fields offered by local clubs; (2) the neighborhood doesn’t provide sufficient recreational spaces or pedestrian pathways; (3) residents are highly satisfied with the neighborhood’s sense of security, privacy and belonging; (4) residents are not satisfied about the areas provided for physical exercises and/or leisure activities. Therefore, the suggested recommendations for implementing the settings of the neighborhood are based on the (A) provision of areas and facilities encouraging physical activities and (B) implementation of green spaces and/or public realm. In turn, the findings provide a tool to policy makers, urban planners and designers for the enhancement of the QOUL of neighborhoods in Qatar.

Keywords:

QOUL (Quality of Urban Life), Built Environment, Human Behavior

Cite this paper: Rana Wadi, Raffaello Furlan, The Quality of Urban Life (QOUL) of New-Salata’s Neighborhood in Qatar, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 14-22. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20170701.03.

1. Introduction

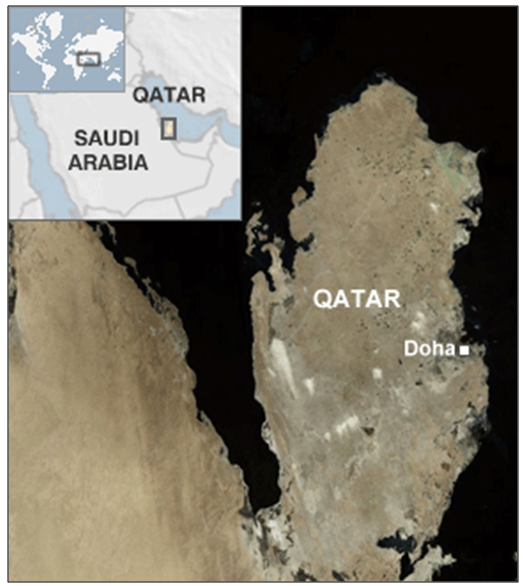

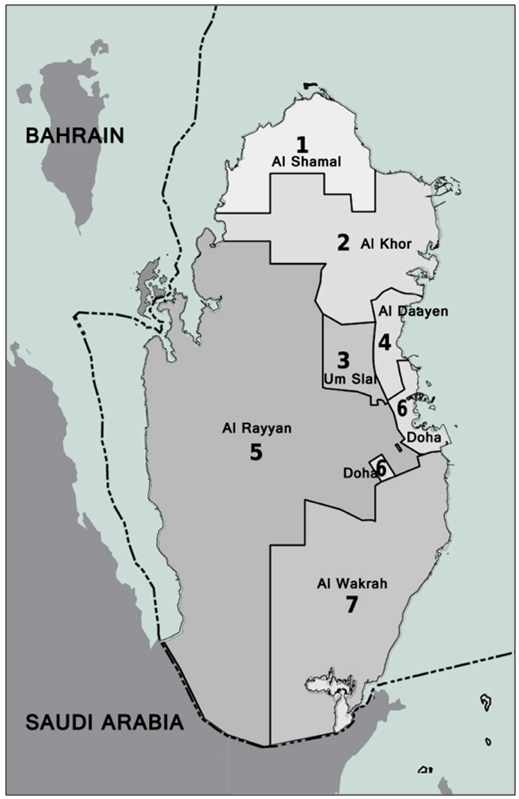

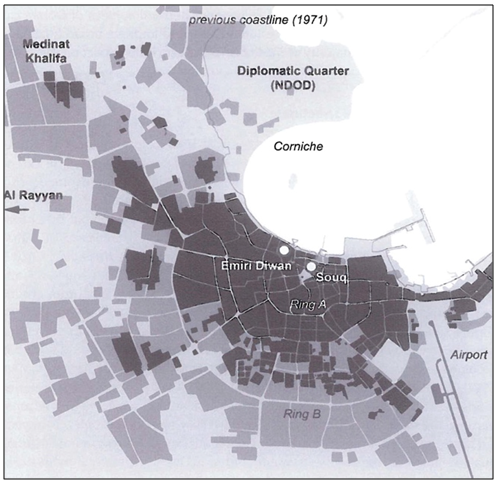

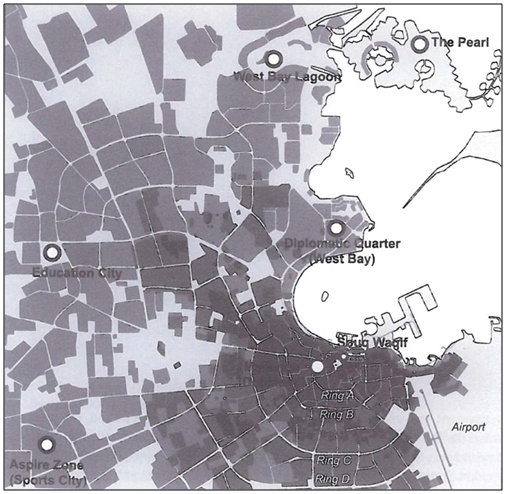

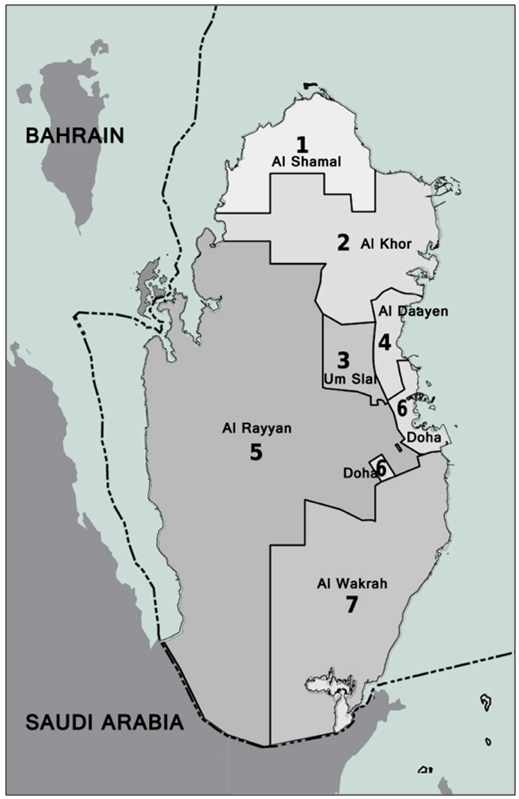

The State of Qatar, located on a peninsula in the Arab Gulf (Figure 1-2), with a coastline of approximately 600km, is a mostly sea level and flat land. Due (1) to the 1950s profitable export of oil, (2) to the 1970s discovery of the world’s largest gas field (known as the ‘North Field’) and (3) to the 1990s production of liquefied natural gas, Qatar went through a recent and rapid urbanization process. Nowadays, Doha, the capital city of Qatar, offers accommodation to expatriates, who reside in neighborhoods and experience long travel of approximately 35 to 50 miles (60 to 80 km) to the capital (figure 1-2). | Figure 1. Geographical Map of Qatar |

| Figure 2. Qatar’s Municipalities |

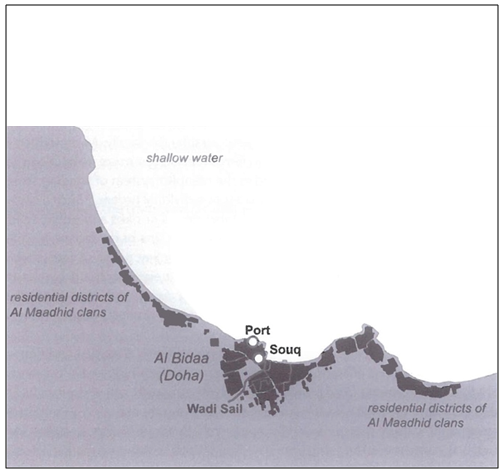

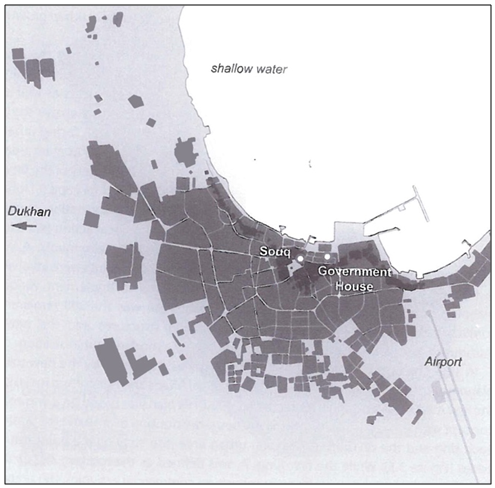

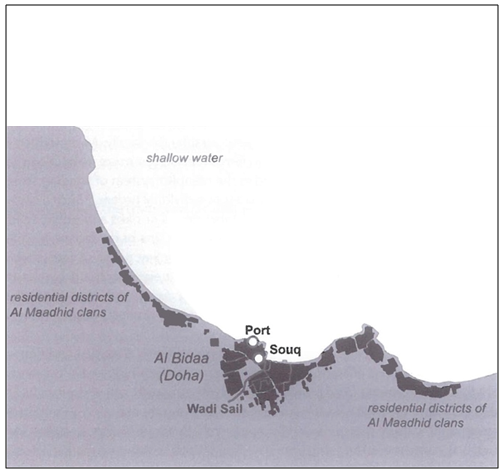

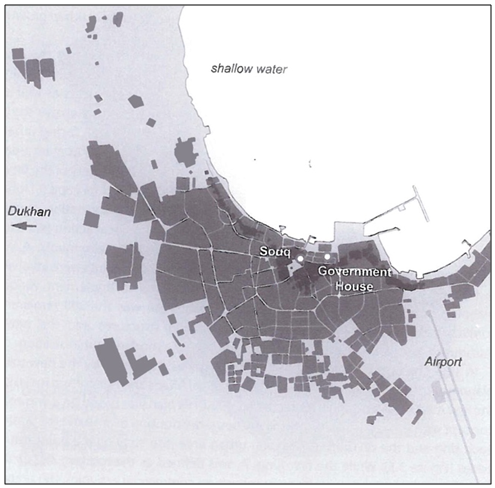

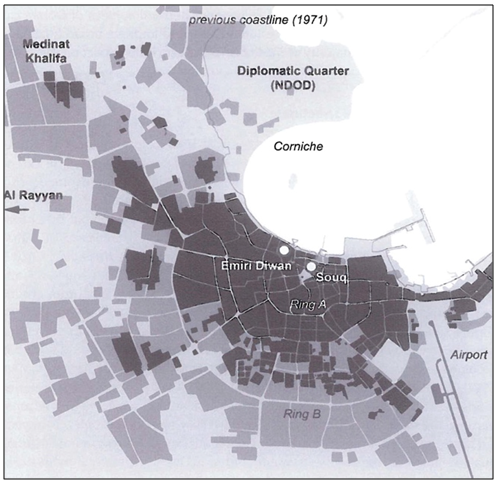

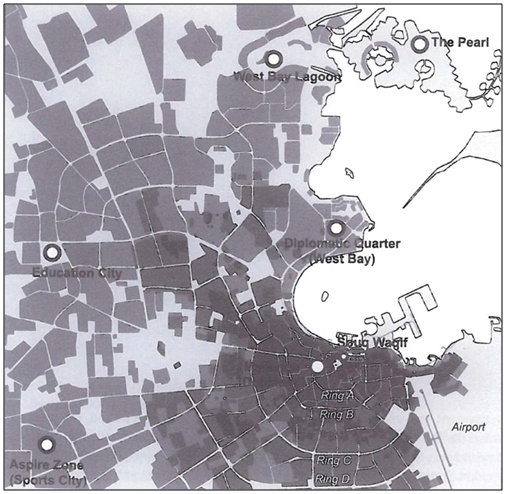

In 1930s, Qatar witnessed poverty, famine and disease prior to any emergence of local architecture (Jaidah and Bourennane 2009). The establishment of ‘Petroleum Development Qatar’ in 1935, highlighted the beginning of an era characterized by a fast urban growth (Salama 2013; Remali, Salama et al. 2016). The oil revenue turned Qatari population into one of the world-widely richest countries. The first school in Qatar was established in 1952 and the hospital was built in 1959. Further large-scale urban developments marked the beginning of large governmental and international investments in the country. Cultural heritage of Qatar was dominant, namely in the design of residential houses, public palaces and open areas (Furlan and Faggion 2015; Furlan 2016; Furlan and Petruccioli 2016).In the 1950s, housing development along with the implementation of infrastructure, drainage, electricity and water distribution, had a cardinal role towards the rapid urban growth of the nation. Housing was the main endeavour, which provided local residents the possibility to develop their construction skills. During this period, several buildings, mainly located around the outer ring of Doha, were built by adopting a specific construction technique: reinforced concrete frame and concrete block infill. Additionally, developments along inner rings of Doha were neglected for decades due to a lack of an urban comprehensive planning strategy (figure 3-4-5-6) (Salama and Wiedman 2013). | Figure 3. Doha’s pre-oil settlements in the 1950s (Salama and Wiedman 2013) |

| Figure 4. Doha’s settlement areas in the 1970s (Salama and Wiedman 2013) |

| Figure 5. The settlement areas in the 1990s (Salama and Wiedman 2013) |

| Figure 6. The past ten years settlement expansion (Salama and Wiedman 2013) |

Recently, urban planning in Qatar envisioned the development of neighborhoods aiming at creating communities away from the town centre of Doha. These neighbourhoods are characterized by different housing types, intended at implementing the lifestyle and /or quality of life of residents within the neighbourhood (Furlan and Almohannadi 2016; Furlan and Petruccioli 2016; Furlan and Zaina 2016).The quality of urban life (QOUL) in residential areas is investigated by measuring (A) objective values based on residents’ physical, social and environmental perception of the living environment, and (B) subjective values, based on residents’ satisfaction about the quality of residential life (Das 2008).Therefore, this research study focuses on investigating the physical settings and the human behaviour and/or activities within the residential neighbourhood of New-Salata in Doha. The purpose is to identify the main parameters that affect residents’ QOUL in the neighbourhood. The findings (1) provide insights into the factors that influence residents’ satisfaction about QOUL, and (2) contribute to define a strategy for designing residential neighbourhoods in Doha.

2. Background

2.1. Quality of Urban Life (QOUL)

The concept of quality of life dates back to philosophers like Aristotle (384–322 BC) who wrote about “the good life” and “living well” and the role of public policy to pursue quality of life. Also, in 1889, Seth wrote: “we must not regard the mere quantity, but also the quality of “life” which forms the moral end” (Marshall and Banister 2007). Quality of urban life has been the focus of several contemporary studies based on different theoretical perspectives and views such as, “the satisfaction in your life comes from having good health, comfort, good relationship etc., rather than from money”, or “The personal satisfaction (or dissatisfaction) is with the cultural or intellectual conditions under which one lives” (Heind 2004).Within a context of time, place and society, specific values contribute to enhance the quality of life. In other words, people’s needs and the fulfilment of their desires can be defined within a specific socio-cultural context: there are elements of quality of life commonly shared a cultural group and/or the members of a society (Marshall and Banister 2007). Generally, health and education are included in most QOUL’s factors. People’s satisfaction about their housing’s settings enhances their psychological state, health and allows them to be more productive. QOUL within a neighbourhood is increasingly associated with a well-planned, healthy and supportive environment. Most of the contemporary urban planning theories such as New Urbanism, Smart Growth, Urban Village and Principles of Intelligent Urbanism, aimed (A) at developing communities that serve successfully the needs of residents and/or users and (B) at constraining the urban sprawl while enhancing QOUL.QOUL within a neighbourhood is affected by different parameters: (1) the environmental QOUL, where there is an access to natural landscapes, clean air, water and land, preservation of resources and minimization of energy consumption; (2) the physical QOUL, where neighbourhood are mixed-used, compacted, walkability is enhanced, a fine network of interconnecting streets and open spaces are clearly defined by well-structured buildings or houses (Din, A et al. 2013); (3) the mobility in urban life, where alternatives to using cars are provided in order to reduce pollution and create a better living environment; (4) the economical QOUL, where there are job opportunities and a potential of having owned business; (5) the political QOUL, where codes and legislations for any future development within the neighbourhood promote the involvement of the community in decision making (Din, A et al. 2013). Namely, the last two parameters, which are related to sociology, play a critical role in enhancing QOUL, because people tend to relate any change to their life to their social conditions: as a result, this research study investigates the social aspect of QOUL (Din, A et al. 2013). The social QOUL promotes social justice and equality by providing affordable housing, economic activities, services and facilities within the neighbourhood. Eliminating boundaries and high-gated walls, achieving privacy and safety through the design of streets and houses and promoting social integration by providing different housing types contribute to social QOUL. Namely, the provision of public spaces acting as hubs to gather people of different nationalities offers an opportunity for social integration, which, as anticipated, plays a cardinal role in shaping QOUL. In addition, the psychological QOUL, based on promoting community identity by preserving heritage and making architecture responding to its context is also of extensive value and, therefore, contribute to enrich people’s satisfaction about QOUL (Din, A et al. 2013).Also, according to Szalai in Kamp et al. (2003), the quality of life refers to “…the degree of excellence or satisfactory character of life. A person’s existential state, well-being, satisfaction with life is determined on the one hand by exogenous (objective) facts and factors of his life and on the other hand by the endogenous (subjective) perception and assessment he has of these facts and factors, of life of himself.” Therefore, residents’ QOUL depends, to a large extent, on the individuals’ sociological and psychological well-being, life satisfaction, happiness, and wellness.In addition, scholars stress that resident defines a neighbourhood according to his/her own life style. Lynch (2007) defines this as ‘imageability’: ‘…every user and resident translates these elements due to his life experience in the neighbourhood and his own understanding and his own uses.’ A neighbourhood should enclose different public spaces and facilities utilized for different recreational purposes. The physical setting of a neighbourhood relates to housing, services, and circulation patterns. The extent to which residents interact with the physical environment contributes predominately to the QOUL. This assertion highlights that the quality of urban life has both an objective and a subjective component: it requires an investigation of both components and the relationship between them in order to understand the level of QOUL within a neighbourhood (Qawasmeh 2014).In Qatar, people of different nationalities co-reside within neighbourhood. Well-designed neighbourhoods give a sense of belonging and encourage social activities between users. Mixed use developments and housing types can be more attractive when their spatial form and configuration contribute to enhance social activities (Furlan, Almohannadi et al. 2015; Furlan and Faggion 2015; Furlan 2016). In Qatar, a variety of housing types is offered in different neighbourhoods (Furlan and Petruccioli 2016). Scholars stress that the development of neighbourhoods is based on enhancing a mix-used compact setting, characterized by residential, educational and commercial buildings, which in turn contributes to the QOUL. This study aims at assessing the social aspect of the QOUL in the New-Salata neighbourhood. It is auspicated that the outcome from this research study will provide recommendations and/or guidelines to authorities to enhance the QOUL of neighbourhood in Qatar.

2.2. The Research Design

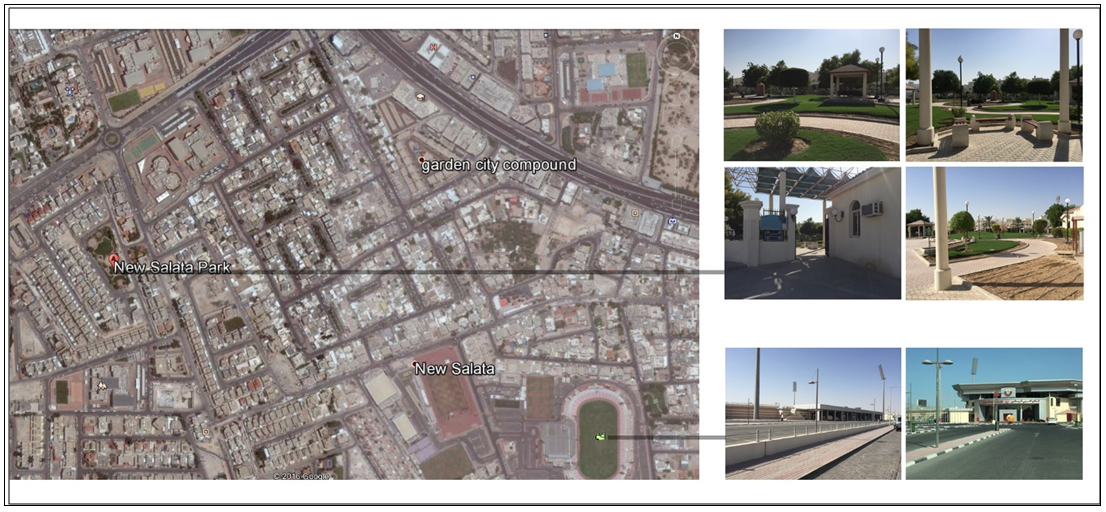

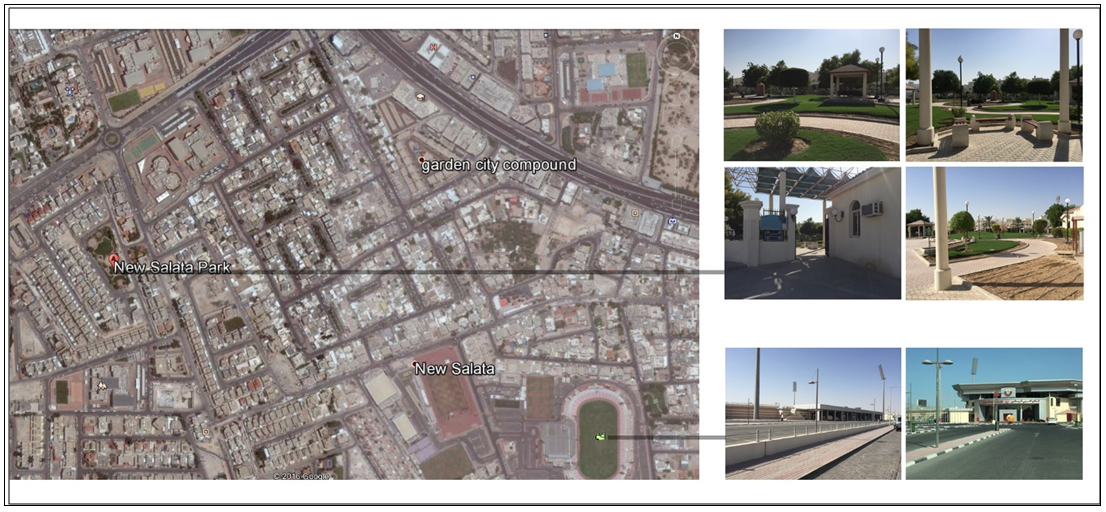

New-Salata is a neighborhood located within Al-Asiri district in Doha (Figure 7-8). It is a compacted neighborhood, consisting of residential compounds enclosing private villas, apartments and townhouses. The neighborhood displays a variety of housing types and facilities. The existing facilities in the neighborhood consist of schools, kindergartens, mosques, sports club, skills development center, beauty spas and a small public park. The neighborhood is accessed through four main roads and the plots or residences are accessed through internal private and semi-private roads. This research study aims to assess the QOUL and residents’ satisfaction within the selected neighborhood. | Figure 7-8. Maps of the New-Salata neighbourhood |

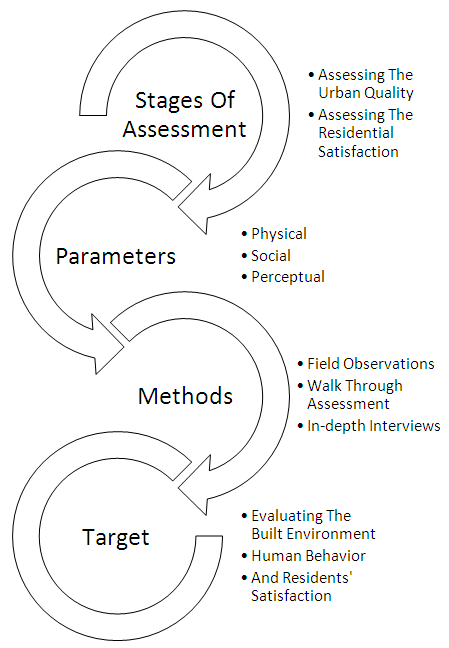

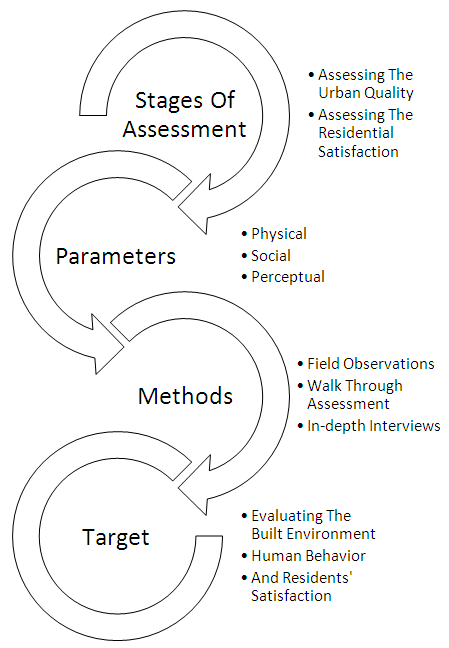

Therefore, the theoretical framework of this research study is structured into two stages: assessing (1) the urban quality of the built environment and (2) residents’ level of satisfaction. The two stages are tested through three parameters: (A) the physical environment, (B) the nature of social interactions and (C) the way residents perceive the neighbourhood. The concurrent analysis of the built environment and users’ human behaviour within the selected neighbourhood is undertaken using three main methods: field observations, walk through assessments and in-depth interviews (Zeisel 1975; Zeisel 1984; Mason 2001; Creswell 2003; Denzin and Lincoln 2005; Charmaz 2006) (Figure 10).  | Figure 10. QOUL research framework diagram |

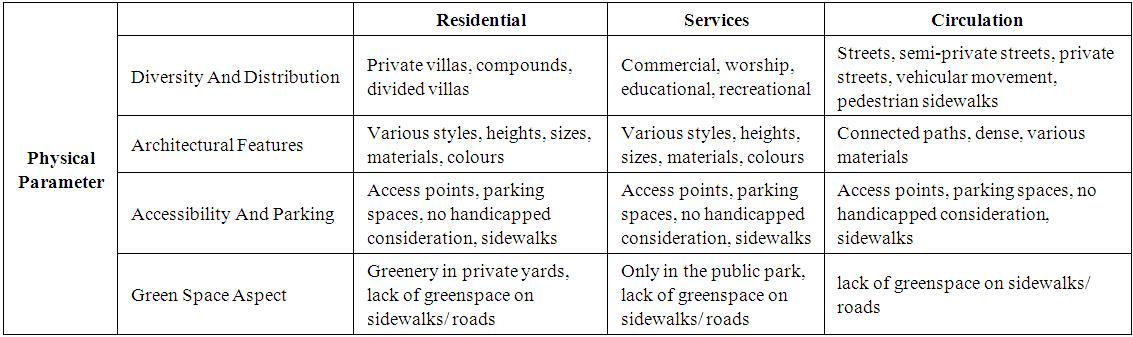

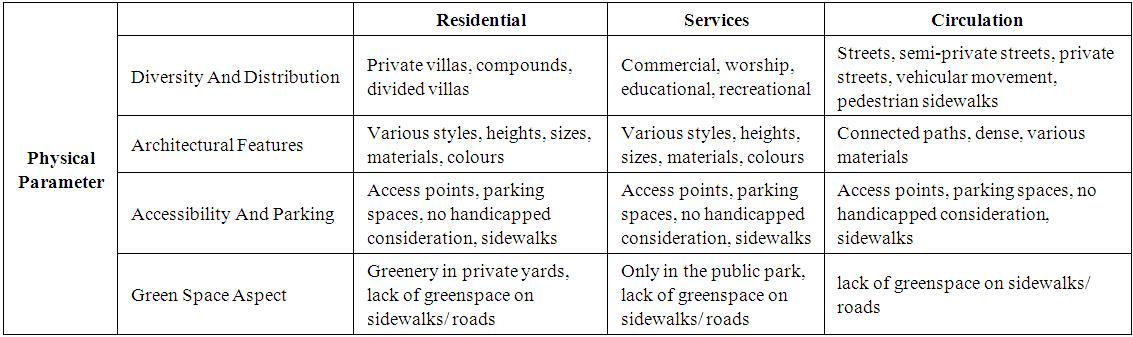

(A) The physical parameter deals with the investigation of the existing residential buildings, services and circulation elements within the neighbourhood. These are categorized according to diversity, architectural features, accessibility and landscape features. The outcome of this partial investigation is highlighted in a table showing the physical characteristics of the neighbourhood and through the collected visual material (Figure 11-12-13-14).(B) The social parameter deals with users’ human behaviour within the facilities and public spaces of the neighbourhood. The investigation consists of on-site observations of the main attracting nodes of the neighbourhood and the activities hereby performed. (C) The perceptual parameter deals with users’ needs and satisfaction about the surrounding built environment. This includes residential satisfaction, attachment to their living area, enjoyment, sense of belonging and sense of place. Richman introduced a categorization of needs as a tool of assessment: (1) the need to escape from stresses, (2) the need to be surrounded by natural landscape (vegetation), (3) privacy, (4) the need for security and safety, (5) the sense of belonging (6), social recognition and status, (7) physical exercise and physical activity services, and (8) tension release (Richman 1979).

3. Findings

3.1. Physical Parameter

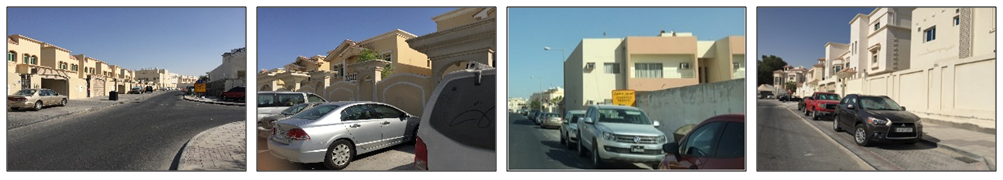

The physical parameter presents the existing residential buildings, services, and circulation elements of the neighbourhood that were categorized according to diversity, architectural features, accessibility and landscape features. The main features were noted with the support of photos to illustrate the current condition of the neighbourhood before analysing the social and perceptual parameters. Results are shown in the following table and photos (Figure 11-12-13-14). | Figure 11. Characteristics of the neighbourhood |

| Figure 12. Residential buildings |

| Figure 13. Public spaces and services |

| Figure 14. Roads |

The physical environment of the New-Salata neighbourhood has different residential buildings, services and circulation paths. Residential buildings consist of villas of different sizes and architectural styles, being the plots owned by individuals who have the freedom to customize their own residences. Ownership of plots in Qatar is only allowed to Qataris. Non-Qatari residents in such neighbourhoods usually rent small villas or sub-divided villas from their Qatari owners. Few villas share the same style and size and usually these are the rentable ones. The building regulations in Qatar usually deal with setbacks, heights and location of openings to guarantee privacy and other regulations related to the percentage of built up and covered area only. Parking spaces are located within the plots and in some cases located on the exterior pavement, shaded by shading devices. Cars of non-residents are parked on random locations, on the sides of the roads and in some cases besides the entrance to the villas. Green spaces in residential buildings are located only within the boundaries of each plot.Services consist of a variety of schools for males and females, as gender separation is a concern in Qatar. For worship purposes, mosques are distributed in the neighbourhood. One local sports club is located in the neighbourhood with different facilities and courses for different age groups of the residents. Also, the courts of the sports club are open to the public in the evenings. Green spaces are also within the boundaries of each facility in courts, small planter boxes or yards. The public park is surrounded by high boundary walls, which do not create a pleasant view from outside. In relation to vehicular circulation, the main roads within the neighbourhood are considered to be semi-private and surrounded by villas. These roads are wider than those leading to groups of villas. The roads are well connected and the different facilities act as nodes within the neighbourhood. Also, there is a lack of bicycle lanes and pedestrian paths/network. All roads are easily accessible and well connected. Parking spaces are available by the sides of the roads and the new development is creating new on the wide semi-private roads.

3.2. Social Parameter

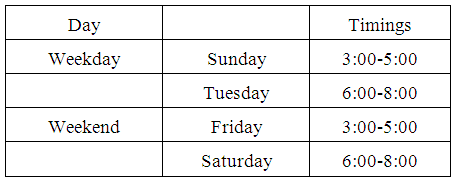

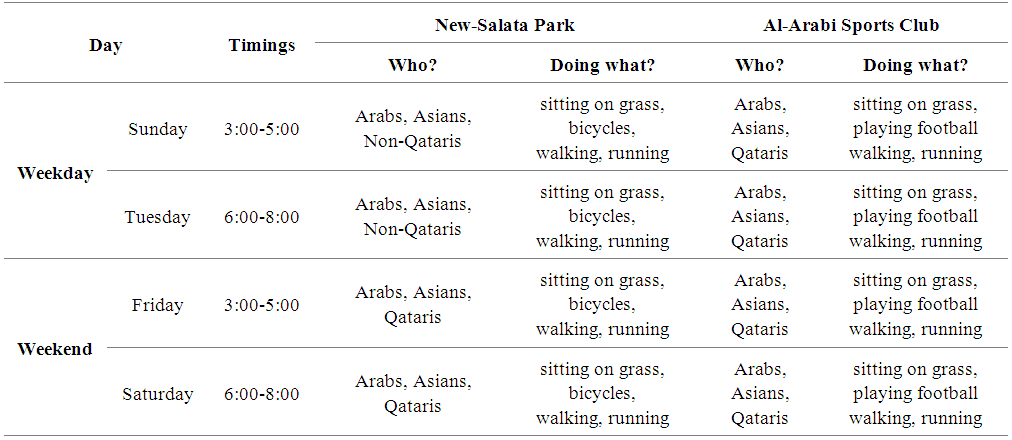

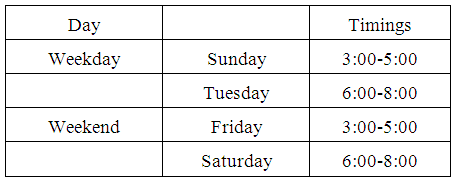

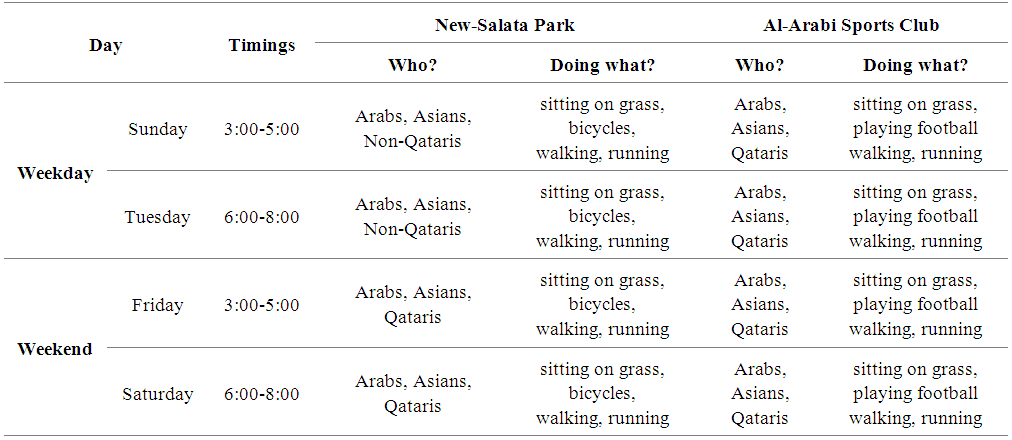

The social parameter of the study deals with the extent to which residents behave and interact within the built environment. This section examines human behaviour and interaction within the facilities and public spaces of the neighbourhood. The investigation consisted of on-site observation of the number of residents in the main attracting nodes of the neighbourhood concurrently with the performed activities (Figure 15). The selected timings for site-observation were based on working and schooling hours (Figure 16-17). | Figure 15. Timings of the observation |

| Figure 16. Analysed places of the observation |

| Figure 17. Results of observation |

During weekdays, groups of Arabs and Asians were present at the park. Unlike the public park, the use of bicycles is not allowed in the sports club. The activities in the sports club were limited as the courts are open to the public with no guidance so people would be walking, running and playing football in the green field. From the number of residents observed, the two places seemed not of great interest to residents. The reasons might be related to the regulations of the sports club and to the distant location of the park and sports club.

3.3. Perceptual Parameter

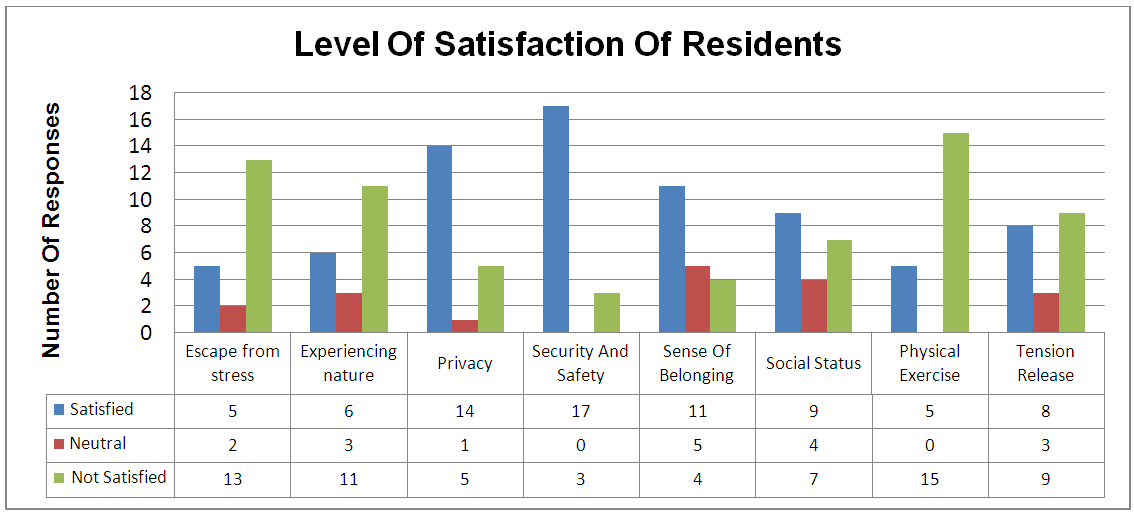

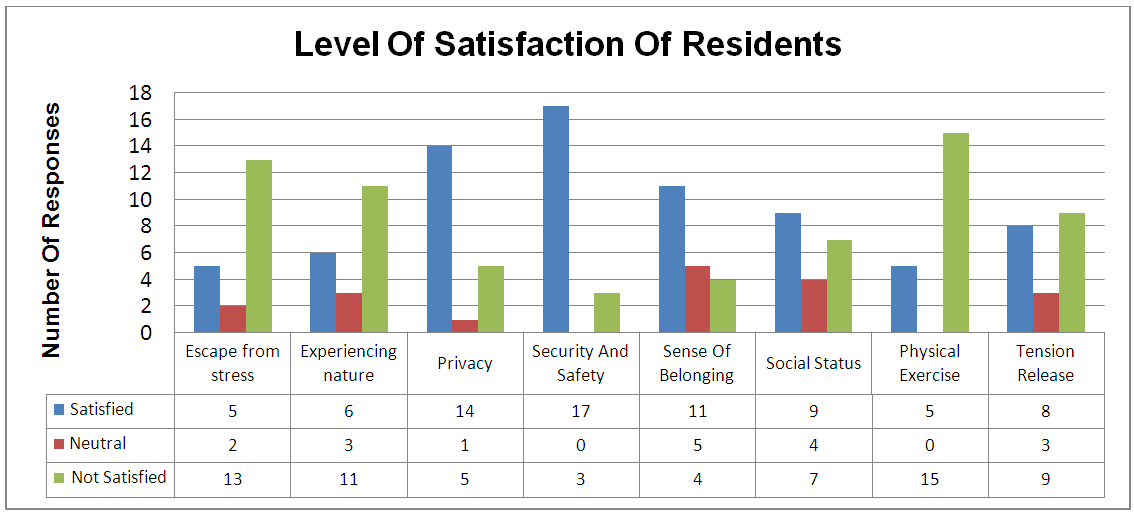

Perceptual parameter is classified under the level of residential satisfaction and residential sense of belonging to the neighbourhood. Residential satisfaction is accomplished if/when the needs of residents are satisfied. Richman introduced a categorization for the needs of residents in a neighbourhood as follows: (1) the need to escape from stresses, (2) the need to view nature (vegetation), (3) the need for privacy, (4) the need for security and safety for self and family, (5) The need for a sense of belonging (6) and social recognition and status, (7) the need of physical exercise and physical activity services, and (8) the need for tension release (Richman 1979). The insights of Richman constitute a tool of assessment of residents’ needs within the research study. Different nationalities residents (4 Qataris, 4 Asians, 6 Arabs, 2 European and 4 others) were selected randomly for the investigation. The categories envisioned by Richman were investigated through an evaluation of the level of satisfaction of residents (figure 18). | Figure 18. Level of satisfaction of residents |

The responses reveal that residents are highly satisfied with the sense of security privacy, belonging and safety within the neighbourhood. All villas of the neighbourhood are surrounded by high boundary walls, which provide privacy to the private yards of each house. Residents are not satisfied about the provided areas for performing physical exercises, releasing tension and escaping from stress. Few residents only don’t like the public park or walking in the field of the sports club. They argue that these two destinations are limited in terms of views and space. Residents prefer to see the sea whenever they’re stressed and/or experiencing an appealing water feature, which contribute to relax and relieve stress. Most residents stress the need to provide further areas for jogging or walking, which could be accomplished by developing a pedestrian network within the neighbourhood.

4. Conclusions

The aim of this research study was to assess the QOUL of New-Salata neighbourhood in Doha. The assessment was accomplished through the evaluation of the urban settings’ quality and residents’ satisfaction. The findings reveal that the physical environment of New-Salata neighbourhood has various residential buildings, facilities and circulation paths; there are various sizes/scale and architectural styles of villas; there is a lack of parking spaces and green spaces around the residential buildings. The public park doesn’t have a pleasant view from a distance and greenery can only be seen from inside the park. Other public facilities are the sports club where the fields are open to public during specific hours of the day. Roads of the neighbourhood lack pedestrian pathways, greenery and public parking. For the social parameter, residents revealed that the two active places in the neighborhood are the public park and the local sports club. Residents tend to walk, sit and run, being the use of bicycle not allowed in the sports club. Residents stress the need to have more facilities to encourage physical exercising: the sports club has few constraints. Within the neighbourhood green spaces are neglected and/or lacked. The addition of green areas by the sides of the roads, such as trees and small shrubs, could provide an appealing view to residents and also enhance shade on the sides of the roads. Having pedestrian walkways and bicycle lanes would facilitate people to freely do physical exercising around the neighbourhood.

Implications for Practice and Advancement of Research

This research study contributes to the development of residential neighborhood in Qatar. Attention of authorities and policy makers should be directed towards implementing strategies to improve the quality of urban life in neighborhood in Qatar. Also, in order to achieve a better quality of urban life for existing communities, specific priorities must be identified. These priorities must be extrapolated from the findings of investigative studies where appropriate qualitative standards and methodologies are adopted to determine residents’ perceptions of the built environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Rana Wadi graduated from the department of Architecture and Urban Planning at Qatar University in June 2015 with a high distinction award. Currently, she is undertaking a Master’s Degree in Urban Planning and Design at Qatar University. Raffaello Furlan has 18 years work experience as an architect. He has been involved in managing the design and construction of residential and commercial developments from inception through to completion. He has 10 years teaching experience at university.The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Qatar University for creating an environment that encourages scientific research. This research study was developed as an assignment at the core-course ‘Urban Design in Practice’ (MUPD-711, Fall-2016) for the Master in Urban Planning and Design (MUPD) and ‘Adv. Spec. Top. I in Urban Planning’ (PHUP751, Fall-2016) for the PhD program at Qatar University, College of Engineering, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning (DAUP), taught by Dr. Raffaello Furlan. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the leading planners and architects from the Ministry of Municipality and Urban Planning (MMUP), Ashghal-Public Works Authority and Qatar Rail for their collaboration, for participating in the meetings, handling relevant visual data and cardinal documents to the research aims and finally to discuss the conclusive results of this investigation. Finally, the authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which contributed to an improvement of this paper. The authors are solely responsible for the statements made herein.

References

| [1] | Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications. |

| [2] | Creswell, J. (2003). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, California, Sage Publications. |

| [3] | Das, D. (2008). "Urban Quality of Life: A Case Study of Guwahati." Social Indicators Research 88(2): 297-310. |

| [4] | Denzin, N. K. and Y. S. Lincoln (2005). Handbook of Qualitative Research. London, Sage Publications. |

| [5] | Din, S., F. A, et al. (2013). "Principles of urban quality of life for a neighbourhood." HBRC Journal 9(1). |

| [6] | Furlan, R. (2016). "Modern and Vernacular Settlements in Doha: An Urban Planning Strategy to Pursue Modernity and Consolidate Cultural identity." Arts and Social Sciences Journal 7(2): 171-176. |

| [7] | Furlan, R. (2016). "Urban Design and Livability: The Regeneration of the Corniche in Doha." American Journal of Environmental Engineering’ 6(3): 73-87. |

| [8] | Furlan, R. and M. Almohannadi (2016). "Light Rail Transit and Land Use: An Integrated Planning Strategy for Al-Qassar’s TOD in Qatar." International Journal of Architectural Research-ArchNet-IJAR’ 10(3): 170-192. |

| [9] | Furlan, R., M. Almohannadi, et al. (2015). "Integrated Approach for the Improvement of Human Comfort in the Public Realm: The Case of the Corniche, the Linear Urban Link of Doha." American Journal of Sociological Research 5(3): 89-100. |

| [10] | Furlan, R. and L. Faggion (2015). "The Development of Vital Precincts in Doha: Urban Regeneration and Socio-Cultural Factors." American Journal of Environmental Engineering 5(4): 120-129. |

| [11] | Furlan, R. and L. Faggion (2015). "The Souq Waqif Heritage Site in Doha: Spatial Form and Livability." American Journal of Environmental Engineering 5(5): 146-160. |

| [12] | Furlan, R. and A. Petruccioli (2016). "Affordable Housing for Middle Income Expats in Qatar: Strategies for Implementing Livability and Urban Form." International Journal of Architectural Research-ArchNet-IJAR’ 10(3): 138-151. |

| [13] | Furlan, R. and S. Zaina (2016). "Urban Planning in Qatar: Strategies and Vision for the Development of Transit Villages in Doha." Australian Planner Dec 2016: 1-16. |

| [14] | Heind, O. (2004). "Space Energy and Total Thermal Comfort." Faculty of Engineering Cairo University. |

| [15] | Jaidah, I. M. and M. Bourennane (2009). The History of Qatari Architecture from 1800 to 1950, Skira Editore. |

| [16] | Lynch, K. (2007). The Image of the Environment and The City Image and Its Elements, Routledge: New York, NY, USA. |

| [17] | Marshall, S. and D. Banister (2007). "Land Use and Transport." Elsevier. |

| [18] | Mason, J. (2001). Qualitative Researching. London, Sage Publications. |

| [19] | Qawasmeh, R. (2014). "Identification Of The Quality Of Urban Life Assessment Aspects In Residential Neighbourhoods In Doha." WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 191: 391-402. |

| [20] | Richman, A. (1979). "Planning residential environments: the social performance standard." Journal of the American Planning Association 45(4): 448-458. |

| [21] | Salama, A. and F. Wiedman (2013). Demystifying Doha. Uk, Ashgate Publishing Limited. |

| [22] | Van Kamp, I., K. Leidelmeijer, et al. (2003). "Urban environmental quality and human well-being: Towards a conceptual framework and demarcation of concepts; a literature study." Landscape and urban planning 65(1): 5-18. |

| [23] | Zeisel, J. (1975). Social Science Frontiers.Sociology and Architectural Design. New York, Russell Sage Foundation. |

| [24] | Zeisel, J. (1984). Inquiry by Design: Tools for Environment-Behaviour Research. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML