Buzuayew Hailu Asfaw

Sociology Department, Jigjiga University, Jigjiga, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Buzuayew Hailu Asfaw, Sociology Department, Jigjiga University, Jigjiga, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The aim of this study was to explore the dynamics of Agro-Pastoralist -Extension Workers Communication in Jigjiga and Gursum Districts. A combination of data collection techniques like household survey, in-depth interview, FGD and field observation were employed to collect qualitative and quantitative data.By using probability-sampling techniques, 36 household heads and 14 extension workers were selected from the study kebeles. The study shows that most of extension workers (92.9%) believe that agro-pastoralists are satisfied by their services while only (44.5%) agro-pastoralists are ‘satisfied’ enough by extension workers services. Another finding regarding advices given by extension workers of all agro-pastoralists respondents 55.6% of them stated that they agree. Agro-pastoralists moans include extension workers are not motivated to serve their client and engagement of extension workers in non-agricultural related activities. However, lack of regular trainings, incentives and shortage of educational promotion were the main complains of extension workers. Thus, there is a need of establishing a forum where the collaboration of agro-pastoralists and extension workers can be strengthened though continuous trainings.

Keywords:

Agro-pastoralists, Challenge, Communication, Extension workers, Sampling

Cite this paper: Buzuayew Hailu Asfaw, The Dynamics of Agro-pastoralist - Extension Workers Communication: Maiden Evidence from East Ethiopia, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 7-13. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20170701.02.

1. Introduction

Agriculture in Ethiopian economy contributes 50% of gross domestic production (GDP), and employs 85% of the population and the main income-generating sector for the majority of the rural population [1]. It also generates 90% of the foreign exchange earnings [2]. Despite its national economic importance, the sector has remained at subsistence level. Recurrent and prolonged drought, environmental degradation, lack of inadequate financial services and human capital, weak markets and poor infrastructure are believed to have responsible for low productivity of the sector [1]. Given Ethiopia’s history of chronic food insecurity and recurrent catastrophic famines, it is hardly surprising that food security has always featured strongly as a priority in successive Government development plans and strategies [3]. The current development policies entitled ‘Agricultural Development Led to Industrialization’ (ADLI) and the ‘Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty’ (PASDEP), which are ratified by the incumbent government, are good examples to show the commitment made by the government [4]. As to achieve agricultural policies like the above one, the lion share of the responsibilities rely mainly on the development agents. Development Agents (DAs) are considered critical stakeholders in the agricultural development strategy, in nearby assisting and consulting the farmers [5, 6]. According to International Food Policy Research Institute [7] report, there are about 45,812 Development Agents (DAs) on duty in kebeles all over the Ethiopia. Few studies in the field have emphasized the competence problem of the development agents [7-10]. Effective extension service involves maintenance of the knowledge and skill of development agents [5, 9].Due attention to the technical competence and performance of extension workers highlights the relevance of their knowledge, skills and orientations that agricultural educators and employers assume essential. Technical skills involve not only knowledge of the discipline but also the ability to impart that knowledge to learners. As the above researches’ findings indicate, the DAs competence problem is caused from poor education background, lack training, lack of coordination, irregularity and limited in-service training and lack of on-farm experience [7]. Despite the above attempts, all previous studies were focused on highland areas of the country while in agro-pastoral areas yet not uncovered. Methodologically, researchers only took DAs as their unit of analysis (mainly focusing of their competency) but neglected the view of the farmer or rural people. Besides, they gave no or less consideration on the dynamic features of agro-pastoralists- extension workers relationship and its impact on the successive resultant of the extension work in Somali region. Thus, it is difficult to assert that studies undertaken elsewhere in Ethiopia about the farmers-DAs interaction are representative of agro-pastoralists in Somali region. Thus, this research gave broader analysis on the dynamics of agro-pastoralist and extension workers’ communication in Jigjiga and Gursum Districts.

2. Research Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

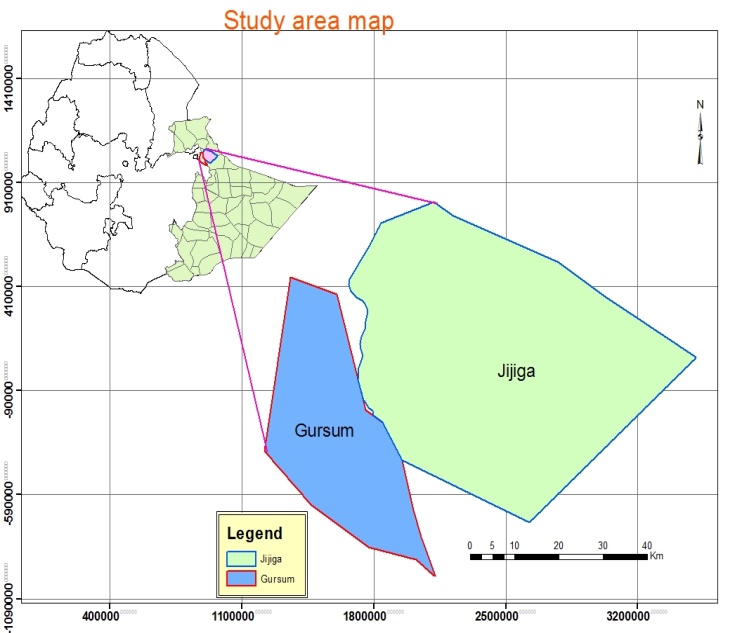

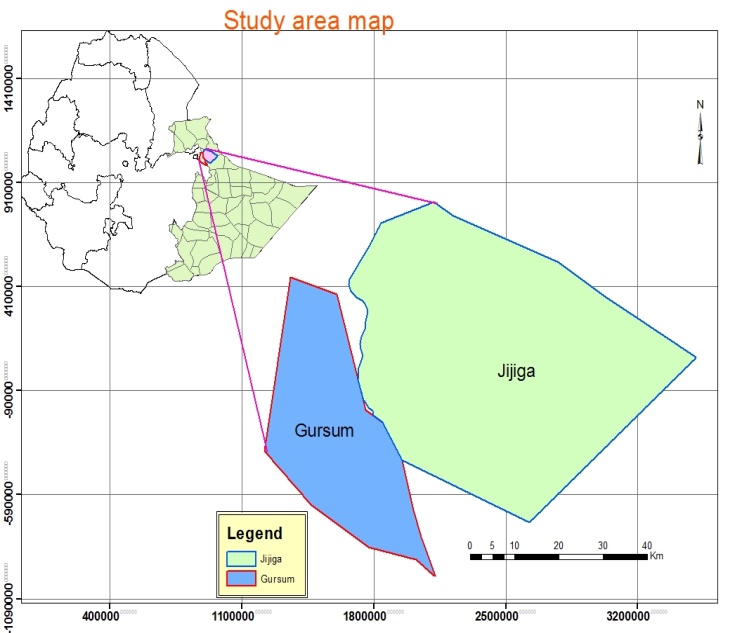

The study was conducted in Jigjiga and Gursum Districts of Fafan Zone, Somali Regional State of eastern Ethiopia. According to [11], Jigjiga District has a total population of 334,674 of whom 177,092 (53%) are men and 157,582 (47%) are women; 180,491 (54%) are rural and 154,584 (46%) are urban dwellers. The district receives an annual rainfall that varies from 500 to 600 mm [12]. The district is known by smallholder agro-pastoral farming system, where mixed farming is well known and practiced by the farmers and agro-pastoralists. Sorghum, maize, barley, wheat, and bean crops are cultivated. Livestock kept include camel, cattle, sheep, donkey and goats [13]. Gursum Districts is located between 9.35° N latitude and 42.38° E longitude. According to [11] the District has a total population of 32,846 of whom 17,275 (53%) are men and 15,572 (47%) are women; 3,637 (11%) are urban and 29,209 (89%) are rural dwellers. The largest ethnic population of Gursum District is Somali people (99.14%). The district is characterized by bimodal type of rainfall classified as a short from March to April rainy season and a main rainy 890.55 mm. The mean annual temperature of the area is 28.21°C. The farming system of area is mainly agro-pastoralism and they mostly produce sorghum, maize, wheat, and khat. Camel, cattle, sheep, donkey and goats are the main livestock types kept in the study area [13]. | Figure 1. Map of the study area |

2.2. Research Methods

Cross-sectional study design composed of qualitative and quantitative approaches was used for the study. Both probability and non-probability sampling techniques were used. Probability sampling was employed to ensure representativeness while non- probability sampling was used for it allows flexibility and reflexivity [14]. Thus, using non-probability sampling, two kebeles: Amedile from Jigjiga and Bombas from Gursum Dstricts were selected since they accommodate farming and agro-pastoral production.Moreover, by using list of households obtained from the districts office as a sampling frame, 360 of household within the study kebeles were randomly drawn by lottery methods. In addition, households from each kebeles were given a 10% representation. Thus, 20 and 16 randomly selected households from sample frame of 200 from Amedile and 160 from Bombas kebeles were taken. Hence, both open and close-ended questionnaire were administered for 36 agro-pastoral household heads and 14 extension workers in both kebeles. In-depth interviews were held with seven community representatives and local government officials. Three separate FGDs were conducted with agro-pastoralists and extension workers. Qualitative data were analyzed textually to substantiate the survey results. To analyze the quantitative data SPSS version 21 with descriptive statistics operations were used to draw an eloquent research results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

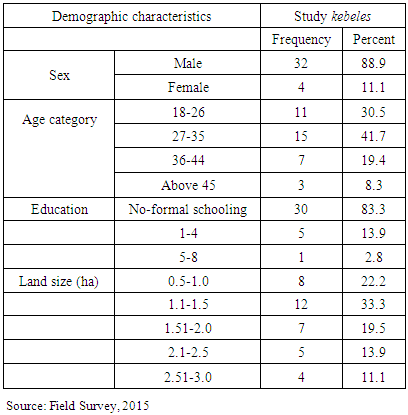

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

|

| |

|

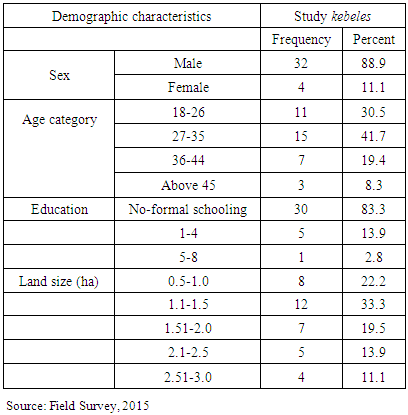

As shown in the above table, of all 36 respondents 32 (88.9%) are male-headed households while the remaining 4 (11.1%) are female headed households. All respondents were between 18 and 50 age group which fall within the economically productive age range for Ethiopia between 15 to 64 years. Concerning respondents’ educational attainment, the finding shows that 83.3% of them do not have the necessary basic literacy that is thought to be very essential for efficient management of agricultural activities and new technologies adoption skills. Access to land is one of the most crucial factors of production. The average size of land holding is represented as 1.75 hectares. The minimum land size owned by the sampled respondents is 0.5ha whereas the maximum land size owned is 3ha. Of all respondents, 22.2% of them have land size between 0.5 to 1 hectare and 52.8% are in the range of 1.1 to 2 hectares, while the remaining 25% fall in the category of 2.1 to 3.0 hectares.

3.2. Agro-pastoralists Views on the Role and Importance of Extension Workers

3.2.1. Agro-pastoralists’ Attitude towards Extension Workers’ Work Competency

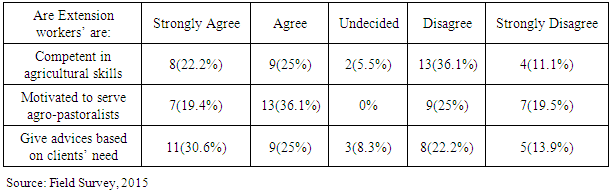

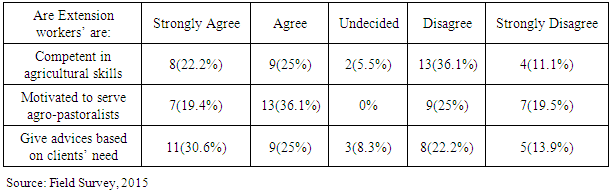

Competent extension professionals are the assets of agricultural extension services. As shown in table 2, of all respondents 17 (47.2%) of them agree that extension workers are competent in agricultural activities, while equally 17 (47.2%) do not agree. On the other hand, 20 (55.5%) of the respondents agreed that extension workers are motivated to serve the agro-pastoralists while the rest 16 (44.5%) do not agree. Nonetheless, four interviewed extension workers express their commitment to serve their client. Drawing from the study result, yet, 11 (30.6%) and nine (25%) of the respondents believed that they ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ with advices given by extension workers, respectively. Whereas, the rest 13 (36.1%) of the respondents totally disagree on the advices given by extension workers.Table 2. Attitudinal score distribution of respondents’

|

| |

|

Here, some of the interviewees agro-pastoralist also disclosed that they were unable to implement the advices of the extension workers for many reasons like high price for purchasing fertilizers, inaccessibility for marketing channels and climate related changes such as natural resource limitations and degradation, water scarcity and increasing desertification. In addition to these, inadequate land and inputs in combination with limited access to information about alternative production technologies were frequently stated by the agro-pastoralists in both kebeles.

3.2.2. Extension Workers’ Competence Level Evaluated by Other Extension Workers’

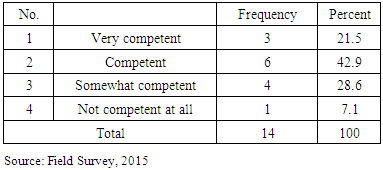

Table 3. Competence of Extension workers assessed by their colleagues (other staffs)

|

| |

|

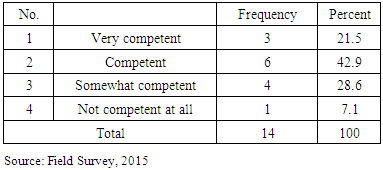

Nowadays extension professionals are judged on how they serve their clients, whether they listen to their clients, how their rapport is with their clients and how familiar they are with their clients’ contexts and issues [15]. The result shows that most extension workers are positive about themselves in relation to their competency level. From the 14 extension workers who participated in the survey, three (21.5%) and six (42.9%) of them stated that their colleagues are ‘very competent’ and competent’, respectively. Conversely, four (28.5%) and one (7.1%) of the respondents stated that their colleagues are ‘somewhat competent’ and ‘not competent at all’, respectively. Yet, extension workers think that they are competent while agro-pastoralists less likely to accept that extension workers are competent enough. During FGDs with extension workers, the issue of competence controversy has been raised within group discussion. It was also found that lack of resources and equipment are creating an impression of extension workers as being incompetent on the parts of agro-pastoralists. That is, as one informant explained the case as follows: “we did not get an opportunity to let the people see what we know. All the time we have been doing almost what ordinary knows.” It is identified that the agro-pastoralists associate competence with receiving specific benefits. According to DAs informants, among people there are inclinations of defining competence of extension workers in terms of benefits they receive from extension workers. For example, those who have varieties of improved seed and fertilizers have positive attitude towards extension workers and consider them as competent, while for several reasons those who did not get the benefits label the extension workers as incompetent. Studies conducted on main competencies for agricultural extension professionals in Ethiopia [5, 10] revealed that farmers are demanding continuous and good quality services than before. Similar to the above findings, this study also shows that extension workers have to be prepared with the necessary knowledge and skills to the minimum meet their clients’ needs.

3.2.3. New Emerging Roles of Agricultural Extension Services

According to [15] the need for active participation of farmers in extension processes, including decision making and collaboration and cooperation among extension service providers in various aspects of extension services, such as in knowledge, information and resource sharing is noted by scholars of the field. In this regard, the study confirmed that the communication and coordination between extension workers and researchers institutions and NGOs is weak. Thus, improving the existing irrigation practices, educating the agro-pastoralist to minimize the impacts of climate change and sustainable natural resource management techniques is vital. In coordination with concerned government and NGOs, moreover, facilitating the market linkage for their products and income-generating activities are also needed.

3.2.4. Agro-pastoralists’ Level of Satisfaction

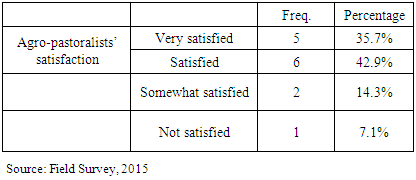

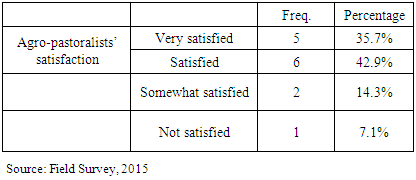

As table 4 shows, about 13 (92.9%) of the extension workers respondents perceived that the agro-pastoralists are satisfied with the services provided by them. Surprisingly enough, most of the extension workers had doubt on the possibility that farmers might be unsatisfied at all. Conversely, the graph below shows the actual satisfaction level of agro-pastoralists with the services provided by the extension workers in both study kebeles.Table 4. Agro-pastoralists’ satisfaction level assessed by Extension Workers’

|

| |

|

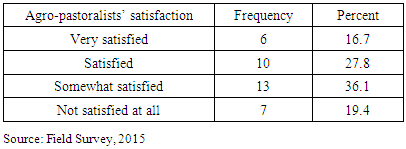

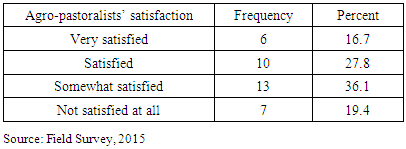

Table 5. Agro-pastoralists’ Satisfaction with the works of Extension Workers’

|

| |

|

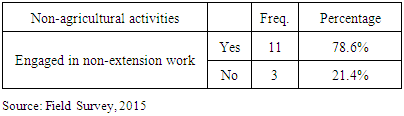

Table 6. Number of Extension workers engaged in agricultural related works

|

| |

|

In the above table, 6 (16.7%), 10 (27.8%) and 13 (36.1%) of the agro-pastoralists respondents said that they are ‘very satisfied’, ‘satisfied’ and ‘somewhat satisfied’ with the service given by the extension workers, respectively. Whereas, the rest seven (19.4%) of the respondent said that they are ‘not satisfied at all’. Here, it is important to crosscheck the satisfaction level of agro-pastoralists as perceived by extension workers and the real satisfaction as specified by the agro-pastoralists. As has been indicated in Table 4, 35.7% and 42.9% of the extension workers think agro-pastoralists are ‘very satisfied’ and ‘satisfied’ respectively. However, from agro-pastoralists’ perspective, only 16.7% and 27.8% of the expected agro-pastoralists said they are ‘very satisfied’ and ‘satisfied’ respectively. This enabled to conclude that there is a disparity between the actual satisfaction level of the agro-pastoralists and the extension workers perceived level of satisfaction of the agro-pastoralists. In-depth interviews and focus group discussion that held with community elders also confirm that there is flaring gap between agro-pastoralists and extension workers communication particularly with the knowledge and practices of agricultural resources over the last two decades.

3.3. Agro-pastoralists- Extension Workers Communication Challenges

3.3.1. Extension Workers Level of Engagement in Agricultural Activities

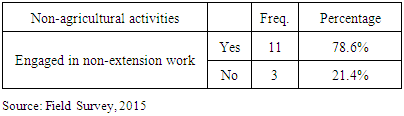

Regarding extension workers involvement in non-agricultural related activities, the survey result revealed that 11 (78.6%) of the respondents are engaged in non-extension activities such as collecting loan repayments (fertilizers and improved seeds) and political activities such as convincing people to vote during election time. Whereas the rest three (21.4%) of the respondents stated that they had never been engaged in it. In this regard, [4] also argue that staff of agricultural extension workers is under pressure to recover the government loans that naturally leads to a selection bias towards households that are perceived as being creditworthy and have potential to generate income from their agricultural activities. In order to be succeed, extension worker should follow central principles such as they should treat the rural people as rational adults who are capable of making their own decisions and interests like politics should be put aside in working with them [16].

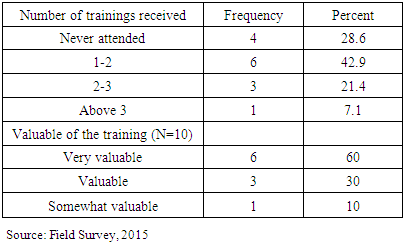

3.3.2. Attending Professional Skill Development

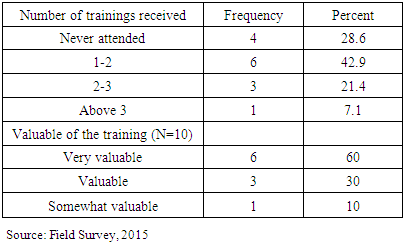

Some research findings showed that there is a great need for competence-strengthening programs through in-service training so that DAs have practice-oriented skills [9]. Extension workers were also asked to indicate how many times over the last 12 months have received trainings and the role of the training for their skill improvement. Of all respondents, 10 (64.3%) of them have attended the trainings 1-3 times in a year while four (28.6%) of them do not attain for various reasons. The one who has attended more than 3 times is due holding extension workers representatives position of the study kebeles. From those who got the chance to attain various trainings, nine (90%) of them have believed that the trainings were useful. Interviews held with extension workers also confirmed that the presence of various skill development trainings helps better to serve the works of agro-pastoralists. Aberra et al. (2001 cited in [9] also suggested that regular on-the-job training for extension agents is essential to disseminate technologies and thereby increase production and productivity of their farmers.Table 7. Extension workers numbers of trainings attended in the past 12 months

|

| |

|

However, few extension workers informants argue the duration of trainings is too short, which makes difficult to understand new technologies and adapt to the local context. The government has focused on extension workers to reach the agro-pastoralists; some of the extension workers have no clear picture on the required task of new approaches that are changing across time. In line with this, one informant clearly state that “the main reason for the less success of those previously introduced new technology in our woreda was it does not incorporate indigenous knowledge and practices.” Besides, extension workers should continuously update their technical knowledge to meet the needs of modern of agricultural industry [9]. Thus, training in the area of their specialty is essential to cope up with advanced knowledge levels.

3.3.3. The Role of Benefit Packages

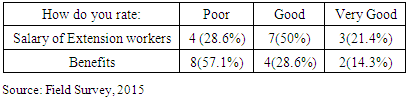

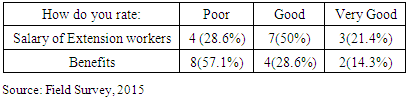

Table 8. Extension workers salary and work incentives

|

| |

|

It is obvious that employees’ satisfaction with their job largely depends on their salary scales and work incentives thus directly influencing their performance in their organization [7]. Similarly, in the study area, attempt was made to assess extension workers satisfaction in relation to their day-to-day work and benefits are received (such as over time fee, salary increment as well as the opportunities for further education that is vital to personal development) with the periods of employment. Thus, individuals are in receipt of benefits as long as employers fulfill their obligation to report to their offices.Concerning extension workers salary, 3 (21.4%) and 7 (50%) of respondents argued that their salary as “very good” and good” respectively while 4 (28.6%) of them said “poor. However, in line with the satisfaction of the works in the incentives packages the pattern of responses is very different to responses given for salary scale. To reduce the rate of turnoff, recently, some extension workers are allowed to pursue their education with the government sponsorship. While other are attaining various private colleges through self-sponsorship.

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Extension workers should possess core competencies such as knowledge, skills, attitudes and behaviors that help them attain excellence in their professions. The study result shows that majority of the extension workers are confident about their competency level while 47.2% of the agro-pastoralists respondents believe that extension workers are not competent. In contrast, 55.6% of the respondent agro-pastoralists stated that advices given by extension workers are based on agro-pastoralists’ need. Similarly, there is a gap between the agro-pastoralists’ actual satisfaction level and as it perceived by extension workers. About 92.9% of the respondent extension workers perceived that the agro-pastoralists are satisfied by services, still, 19.4% of the agro-pastoralists said that they are ‘not satisfied at all’. Besides, most of extension workers reported that the trainings they take were very useful. Lack of clarity of extension operations and weak work commitment to bring agricultural development are identified as challenges. Due to lack of demonstrations made by extension workers substantial agro-pastoralists do not recognize the competence of extension workers. Thus, concerned governmental offices should provide technical and resources support to enable extension workers proficient that help the agro-pastoralists might develop confidence on them. In addition, agro-pastoralists’ level of satisfaction with the services provided by extension workers is identified inadequate. Hence, extension workers should be encouraged to develop a habit of undertaking regular assessments of their works so that they can identify their knowledge gaps by discussing it with their clients. Moreover, involving agro-pastoralists and extension workers in planning and implementation phases are necessary in order to bring the desired changes. Lastly, increasing the role of extension workers in agricultural activities can be achieved through minimizing their involvement in non-agricultural tasks and providing necessary benefits package.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to acknowledge the contribution of data collectors and research assistants. The author also thanks the woredas and kebeles officials for providing the necessary information. Moreover, the author would like to thank all those people who has supported during the fieldwork and for their encouragement and words of comfort. Thank you PIRS for support in finance of the study.

References

| [1] | Tigist, Petros. 2010. Adoption of Conservation Tillage Technologies in Metema Woreda, North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. (Unpublished M.Sc Thesis), Haramaya University, Ethiopia. |

| [2] | Getahun, Degu. 2004. Assessment of Factors Influencing Adoption of Wheat Technology and Its Impact: The Case of Hula Woreda, Ethiopia. (Unpublished M.Sc. Thesis), Alamaya University, Ethiopia. |

| [3] | Elias, E. Dube. 2013. Wireless Farming: A Mobile and Wireless Sensor Network based Application to Create Farm Field Monitoring and Plant Protection for Sustainable Crop Production and Poverty Reduction. (Unpublished Master Thesis) Project 30p. Malmo Hogskola. |

| [4] | Devereux, Stephen and Bruce, Guenther. 2009. Agriculture and Social Protection in Ethiopia. FAC Working Paper No. SP03. www.future-agricultures.org |

| [5] | Wasihun, Berhanu, Kwarteng, Joseph & Okorley, Ernest. 2013. Professional and technical competencies of extension agents as perceived by male and female farmers and the extension agents themselves: The need for data source triangulation. Journal of Agriculture and Biodiversity Research, 2(1), 11-16. |

| [6] | Belay, Kassa and Degnet, Abebaw. 2004. Challenges Facing Agricultural Extension Agents: A Case Study from South Western-Ethiopia. African Development Review. 16(1): 139-163. |

| [7] | IFPRI [International Food Policy Research Institute]. 2009. Review of Agricultural Extension in Ethiopia. On the behalf of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, draft report, June 30, 2009. |

| [8] | Degsew, Melak. 2006. Agricultural Education and Competency of Development Agents in Ethiopia: A Case Study in North Gonder. (Unpublished Master Thesis). AAU, University, Ethiopia. |

| [9] | Degsew Melak and Workneh Negatu. 2012. Agricultural education and technical competency of development agents in Ethiopia. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development. 4(11): 347-351. |

| [10] | Wondimu, Dutamo. 2011. A Study of Farmer-Development Agent Interaction: the case of Soro Woreda, Hadiya Zone, SNNPR. (Unpublished MA Thesis) Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. |

| [11] | Central Statistical Agency [CSA]. 2007. Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census. FDRE. Population Census Commission. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. |

| [12] | Wudie, Bekelu. 2006. Gender Analysis of the Agro-pastoral System Households: The Case of Jigjiga Woreda, Somali Region, Ethiopia. (Unpublished MSc. Thesis), Alamaya University, Ethiopia. |

| [13] | Sisay, Kebede. 2015. Economic Contribution of Camel Milk to Pastoralists Livelihood and Assessment of Feed Resource Availability in the context of Climate Change in Pastoral areas of selected districts of Fafan Zone, eastern Ethiopia. (Unpublished M.Sc. Thesis), Haramaya University, Ethiopia. |

| [14] | Chambers, R. 2007. Poverty Research: Methodologies, Mindsets and Multidimensionality. IDS Working Paper 293. |

| [15] | Murari, Suvedi and Ramjee, Ghimire. 2015. How Competent Are Agricultural Extension Agents and Extension Educators In Nepal? Michigan State University. |

| [16] | Adedoyin, F. and O. A. Onasanya. 2006. Communication Factors Affecting the Adoption of Innovation at the Grassroots Level in Ogun State, Nigeria In: Journal of Central European Agriculture. 7 (4): 601-608. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML