-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2016; 6(4): 111-116

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20160604.03

Subjective Well-Being and Social Networks in Urban Asia

Momoyo K. Shibuya

Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Saitama University, Japan

Correspondence to: Momoyo K. Shibuya , Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Saitama University, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper explores the relationship of the perceived level of life satisfaction with social human networks that individual have in urban Asia. Although existing knowledge suggests that being network-rich and a high level of life satisfaction are potentially correlated, little has been known about that in the Asian urban context. The focus was on life satisfaction and personal relationships of the middle and lower classes in Shanghai in comparison to Tokyo and Bangkok cases, and the data were obtained through a questionnaire survey and supplemental focus group. The analyses of the data found that Shanghai is just in between Bangkok and Tokyo in terms of life satisfaction as well as social networks, but that Shanghai had clearer social stratification than Tokyo or Bangkok did. By showing how people in Shanghai as well as Tokyo and Bangkok live within difficulties, the findings will contribute to further discussions about the concept of urban development and individual well-being.

Keywords: Asia, Subjective well-being, Social network

Cite this paper: Momoyo K. Shibuya , Subjective Well-Being and Social Networks in Urban Asia, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2016, pp. 111-116. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20160604.03.

Article Outline

1. Background

- Seeking economic growth for a better life has come into question in advanced cities. Economic wealth has been commonly believed to be closely connected to the sense of happiness, though it is true only to a certain point (up to $75K of annual income in Kahneman & Deaton, 2010); above the point, ‘happiness paradox’ takes place and income and happiness are no longer correlated (Brickman & Campbell, 1971; Easterlin, 1974; Scitovsky, 1976). In return, people grow more aware than before of quality of life and subjective well-being, and not a few researches have explored the influential factors on it. For instance, Layard’s ‘big seven’ (2005) factors drawn from the US data include social relationships, health, work, personal freedom and values in addition to financial situation. Among those factors, social human relationships have received a large attention as ‘social capital’ since Putnam’s ‘Bowling Alone’ (1995), and an argument has been developed around subjective well-being with human relationships in an urban setting. In fact, some research results indicate that people who can establish human networks and earn a place in the city are healthier as well as happier than those who remain isolated. Tachibanaki and Urakawa (2006) have shown that a high rate of interfamilial interaction correlates with happiness, regardless of income levels. Community relationships are also confirmed to be correlated with the degree of happiness (e.g., Easterlin, 2003; Birkman & Kawachi, 2000; Putnam, 2001).Nonetheless, because western notions of individuality and community relationships are contributing to this conception of social capital, it remains to be seen whether it can be similarly applied in an Asian urban context. Asian cities have experienced a dramatic change in the process of globalisation, and thus, to clarify how people there can improve subjective well-being will serve an opportunity to reconsider our global society and the possible approach to high quality of life in our times.This study, therefore, focuses on the relevance between individual well-being and the characteristics of people’s social networks in East Asia. Urban human relationships are characterised by uniplex ties and intimate-secondary relationship (e.g., Lin et al, 2001; Wireman, 2008). Uniplex ties are a single role relationship, formed between different people according to different aims. Intimate-secondary relationships are, on the other hand, an intimate relationship but without deep involvement as in a primary group. Yet, we still do not have enough knowledge to judge whether or not these characteristics are also found in East Asian cities, and thus a close attention will be paid to there in this study.

2. Methods

- In order to obtain data for achieving the research objectives, this study chose Shanghai as a main research case. In 2010, China overtook Japan as the country with the second highest GDP worldwide, after enjoying double-digit growth rates since joining the World Trade Organization in 2001. As a result, Shanghai in particular, with the urban industrial structure, has sustained a massive population influx from the surrounding rural areas. Cities in East Asia have become spaces offering the lifestyles similar to the world cities as a result of ‘subsidiary integration’ (Yoshihara, 2003) through the process of globalisation, but the Chinese culture also has an influential power in the value system of the East Asian region. Looking at Shanghai’s case would contribute to the further understanding of the East Asian region, as well as being of significance in its own right. The data on subjective well-being and social networks was collected through questionnaire surveys and focus group. The questionnaire surveys were conducted in Shanghai, Bangkok and Tokyo, from 2012 to 2013, for primary earners in the middle and lower households aged 20 or older. Respondents were recruited through an online survey company in each city and selected by stratified sampling. Valid responses were 417 (male 51.1%, female 48.9%) in Shanghai, 769 (male 46.7%, female 53.3%) in Bangkok, and 1256 (male 52.3%, female 47.7%) in Tokyo. Of surveyed, 71.7% were in the middle class in Shanghai, which was a higher ratio than counterparts in Bangkok (53.6%) and Tokyo (49.9%). The questions asking both actual (used) and potential (perceived) social networks were included in addition to self-rated life satisfaction, an indicator of subjective well-being, and all answers were coded and quantitatively analysed. Specifically, the questions went as below:Q22. Are you satisfied with your recent life as a whole? Please rate on a scale of 1 to 10, where 10 is best (life satisfaction/subjective well-being);Q27. When you tried to solve the problem, who actually helped you? (actual social network); and Q30. If the problems/difficulties occur to you, who would you seek help from? (potential social networks) Q27 and Q30 provided choices for answers, and respondents were asked to think of specific persons before they answered each question. The given options were: Spouse; Parent; Parent-in-law; Child; Brother/Sister; Other Relative; Neighbour; Colleague; Friend in social activity; Friend from school; Religious group (temple, church, etc); Other friend; Government; NPO; and Other. For the focus group, participants were recruited through a local research firm for the session held in Shanghai in January 2013. After screening of potential participants based on pre-set criteria such as annual income, age (from 20 to 60 years old), and sex, 12 participants were selected. They were divided into two groups based on income level (the middle and lower classes) prior to the focus group session. The moderator was a local Shanghai-based Chinese, trained by the local research firm, and thus the focus groups were conducted entirely in Chinese. The questions to frame the discussion were: (1) What kind of life do you think is a happy life? (definition of happiness);(2) What are the problems/difficulties with living in a city? (negative influencers); and (3) Who do you consult when you need help? (impact of social capital).All conversations were audio- and video recorded and then transcribed. The transcript was coded for qualitative analysis.

3. Findings

3.1. Life Satisfaction

- All surveyed were asked to rate the degree of life satisfaction on a 10-point scale, where 1 is ‘extremely dissatisfied’ and 10 is ‘extremely satisfied’ (Q22 in the questionnaire survey). The average score of Shanghai respondents was 6.84, while 7.32 in Bangkok and 5.34 in Tokyo. This suggests that Shanghai residents were generally satisfied with their life, at a considerably fair level among Asian cities. The score had no significant differences between sex, marriage status, or income level groups, but the narratives from focus group showed a different picture.In the focus group session, the middle-class group responded that they are ‘reasonably satisfied’ with their present living conditions. They cited ‘to live with family’ and ‘to watch own child(ren) grow up’ as major reasons for feeling happy and satisfied. It does not mean that they have no stressful incidents in daily life. Even when they have, being able to lead ‘ordinary life’, including activities like traveling or dining out with friends, means a lot to them: the phrases like ‘stop comparing with others’, ‘have an attitude of accepting status quo’ and ‘material wealth does not bring you happiness’ were frequently heard in the discussion.There seem reasonably satisfying lives in their own personal space, nonetheless it becomes hard to claim a happy life once they consider the larger society. The urban environment of Shanghai was perceived as a factor obstructing individual well-being, as it exerts a negative influence on their lives due to delay or omission of government’s measures on environmental and social issues. Meanwhile, the stories of the lower class were significantly different from those of the middle class. In response to the question if they are happy, they expressed as ‘not happy’. The reasons why they themselves could not feel happy were mainly ‘having no money’ or ‘being in poverty and living rough’. They understand all problems, difficulties or anxieties they face now are rooted in the lack of money, and thus their definition of a ‘happy life’ emphasises material conditions, that is, sufficient money.

3.2. Social Networks as Capital

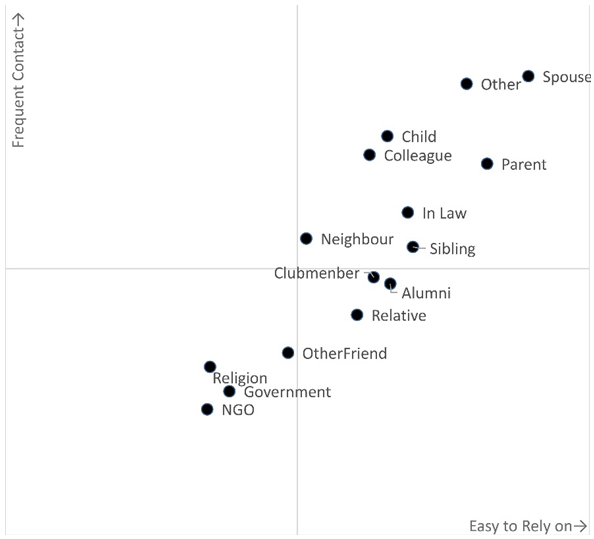

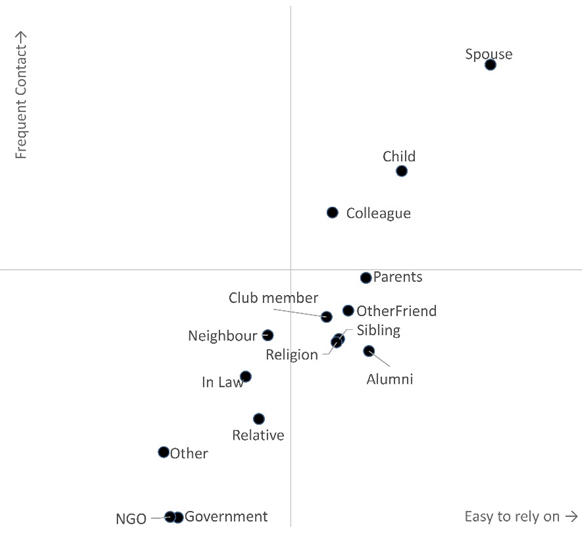

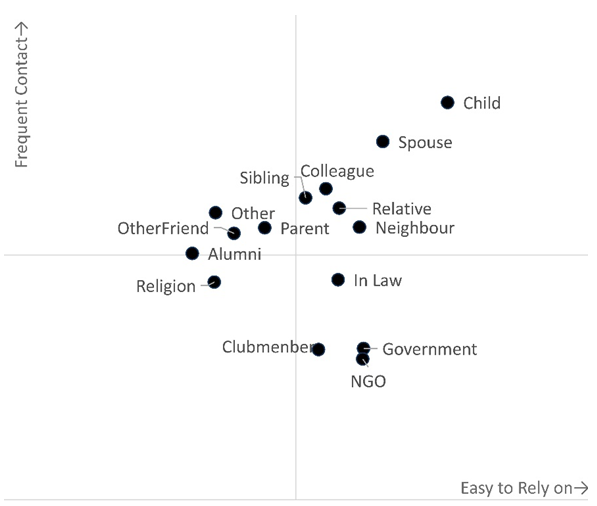

- In Q27 and 30, the respondents were asked their great concerns in the past 10 years as well as in the current situation, and then who helped/would help them. The past problems most frequently answered were: work-related problems (27.1%), living environment concerns (14.1%), and financial situation (11.2%). These three problems were also claimed in Bangkok (financial situation 13.5%, work-related problems 16.1%, and living environment concerns 13.5%), while in Tokyo, health problems (16.3%) came to the third after work-related problems (26.2%) and financial situation (18.3%). That is, Shanghai and other two Asian cities share a certain similarity in this regard. As for their concerns in the current situation, the respondents listed housing cost (18.9%) and living cost (17.8%), followed by inflation (16.3%). Compared to the past concerns, the current ones were heavily concentrated in the financial aspect, and this tendency was similarly found in other cities as well.In the focus group narratives, on the other hand, the middle class group mentioned about health issue. Nevertheless, the health issue here does not mean a simple personal health problem they have. Their narratives are more about concerns for environmental issue (air pollution) and food fraud problems, both of which possibly contribute to insecurity of living environment and a threat to individual health. They bear the high cost of living by understanding it is a result of securing living environment for healthier life, such as buying air cleaners and water filters, importing organic food, and dining out at high-quality restaurants. Like the middle class group, the lower class group also listed health issue. Their concern, however, is stemmed from their poor health insurance: because of the rural household registration, their health insurance does not cover much, which makes them worry about expenses they would pay when they fall ill. For those whose family members are living in hometown, or home village, their concern is more about family’s (particularly parents’) health rather than their own, since they would not be able to go back home to look after them. To solve those problems, the respondents actually asked for support from 1.71 persons, which means a lot of them had more than 1 person, possibly 2 persons, they can connect and become ‘capital’. Once compared with Bangkok (1.91 persons) and Tokyo (1.49 persons), Shanghai seems to have a moderate level of human network community. On the other hand, the respondents answered that they would ask 1.84 persons for a help in facing the current concerns. It is the same that Shanghai comes in the middle, but interestingly Bangkok (1.76 persons) and Tokyo (1.92 persons) switch their position for the number of their potential supports. The supports the respondents relied on depends on the nature of problems. For work-related problems, colleague (33.3%), parent (21.6%) and spouse (13.5%) were the most cited. When living environment became the issue, family members like spouse (63.6%) and parents (50.0%) came first to ask for a help, while alumni fellow (25.0%) became another support other than family members (parent 56.3% and spouse 25.0%) in the financial problem. Potential supports for current concerns, which were mostly financial problems, were parent (19.0%) and spouse (18.5%), followed by brother/sister (10.2%). Although family members similarly came first in Bangkok and Tokyo, minor variations were observed in three cities in how to use other supports such as neighbour, friends, or government.When looking at the nature of each support, more about their social networks can be understood. Figure 1, 2, and 3 depict each city’s social networks, divided by axis X and Y, indicating how easy they can rely on (psychological closeness) and how often they contact (physical closeness) respectively. The first quadrant is where both physically and psychologically close persons are placed; the second one is for physically close but psychologically distant relationships; the relationships fall in the third quadrant is most distant; and the fourth quadrant is where physically distant but psychologically close relationships fall. The number of relationships each quadrant has is, from the first to the fourth 8, 0, 4, and 3 in Shanghai, 6, 3, 2, and 4 in Bangkok and 3, 0, 6, and 6 in Tokyo. From these, it became clearer that Shanghainese put each relationship closer than Tokyo and Bangkok counterparts.

| Figure 1. Social Networks in Shanghai |

| Figure 2. Social Networks in Tokyo |

| Figure 3. Social Networks in Bangkok |

3.3. Life Satisfaction and Human Networks

- On examining the correlation between life satisfaction and personal networks in Shanghai, the fact that only two variables relevant to human environment were statistically correlated with life satisfaction became evident. The one was the number of relatives living nearby and the other was the number of children living together. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were .144 (p<.01) and .126 (p<.05) respectively. Correlated variables differs among three cities, indicating what relationships are significant in their life varies. In Bangkok, the number of workers within family (ρ = .111, p<.01), the number of support (ρ = .151, p<.01) were statistically significant, while in Tokyo, the number of children was significant (ρ = .086, p<.01). This analysis suggests that how close they feel and how much they trust their potential supporters is as important as to whom people perceive to be connected and how many they have such supports. People in Tokyo seem to be happy when they have a good relationship with their own immediate family, children in particular. Bangkok data showed that how much they can extend their network seems important. In Shanghai, on the other hand, the importance of family is seen in a good relationship with relatives. This may be because their situation living and working away from home in order to satisfy their material needs leads the increase of the importance of relatives.The focus group narratives depict such situations well. The lower class work hard to connect with the hometown friends and classmates, or create favourable relationships with new colleagues and in-laws, just in order to avoid the isolation in Shanghai. Some appreciated Shanghai’s tolerance ‘isn’t that bad’; others described their own personal situation as ‘I feel like an outsider’, or ‘I’m lost, wandering in Shanghai’. Regarding family relationship, they are deeply aware of their inability to fulfil their family obligations in leaving home to work in Shanghai. Sentiments like ‘I worry about my parents but I can’t look after them so I feel terribly sorry’, or ‘my brother is looking after my parents but I can’t help out so I feel so guilty’ were repeated in discussion. For the middle class, whose social network is based in Shanghai, the family is simply one of several networks they have and available. They feel that they can trust their family the most, but at the same time utilise their networks of other relatives, colleagues, alumni fellows, and hobby friends, each of which does not overlap with others. They enjoy urban style (uniplex) human relationships, where one should maintain a respectable distance, as in traditional ‘fellowship among the virtuous’.

4. Discussion

- Life in Shanghai is not so simple as described as a subsidiary integrated global city, or as a typical Asian city. It looks different from that in Bangkok or Tokyo, but at the same time, not completely different: Shanghai seems just in between Bangkok and Tokyo. Besides, Shanghai, and other cities as well, has many layers in a society, and life there are quite different to the middle class and the lower class. Correspondingly, they define their sense of well-being differently. The difference is that the middle class defines life satisfaction in terms of living an ‘ordinary life’, whereas the lower class thinks of a satisfactory life as fulfilling all of their material desires. The ‘ordinary life’ described by the middle class is not focused on the physiological needs necessary for survival, but neither is it an ambition to aspire to great heights. The sense of well-being they are seeking is not economic wealth; rather ‘stability’ in the sense that they and their families will be able to continue their middle-class life into the future. The life they are leading can be called urban-type in terms of human environment, surrounded by uniplex networks; their relationships with relatives and friends are selective by necessity and convenience, and they often distance themselves from fellow alumni, who requires multiplex relationships. Meanwhile, the lower class have a strong desire to remedy the situation, due to a clear lack of physical conditions in an ongoing way. At the same time, they feel deeply insecure about their (economic) future, which pushes them to work even in poor conditions to earn money for future and, at the end of the day, draws them into a downward spiral of life. For social networks, they sense an immense deficiency, due to the situation where they are not able to be with their family members. Some are even with guilt over their inability to care for their parents. As their relationships with their families are not being fulfilled, they compensate by relying on a ‘pseudo-family’ or community of fellow alumni and friends from their hometown or province. The constant insecurity of a drifting lifestyle and the high cost of urban living are surely exhausting for them, though more than anything, they are caught in a dilemma as they cannot escape their present lifestyle. They think the source of these various problems is that their physiological needs are going unfulfilled; moreover, for them, satisfying those needs is the path to happiness.In some existing research on social networks, the richness of social networks and subjective well-being or life satisfaction are correlated. However, the findings of this research could not clearly support it. There were some hints of correlative tendencies, but it was not enough to claim the correlation between two concepts. That is to say, the rich social network does not guarantee the owners’ life satisfaction. Difficulties and problems in the urban life are negative factors having an impact on well-being for everyone; however, how middle and lower classes react to such risks differ from one another, and even the degree of impact the same factor gives would vary. Similarly, the factor of family means different for the two groups, resulting in the different level and form of impact would be observed.This study of Shanghainese life satisfaction and social networks in comparison with Bangkok and Tokyo brought us to the starting line in understanding individual well-being in East Asian cities. In future, with the findings here, more qualitative and quantitative research will be designed and carried out in other Asia cities, in order to draw a picture of the world from an Asian perspective and provide better data for thinking through how people can achieve high quality of urban life in East Asia. One hypothesis on the relation between social networks and life satisfaction in Asian cities arises from this study: The quality of social capital would matter more than quantity of it would for life satisfaction, but not always in a direct way. Verifying this hypothesis should wait until the further advanced analysis. At the moment, suggesting this hypnosis is an achievement of this research to open up the discussion around well-being and social capitals in East Asia for future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- This paper is based on a research carried out as one part of a research project on ‘Individual Well-Being in East Asian Cities in the Era of Globalization’, which was conducted with the financial support of the Saitama University Development Fund (2011-2014).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML