-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2016; 6(2): 49-55

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20160602.02

Gender Perspectives in School Health Policy Implementation among Girls in Usigu Division Primary Schools, Siaya County, Kenya

Otiato S. O.1, Omondi D. O.2, Abong’o B. O.3

1Department of Public and Health, Maseno University, Maseno Township, Kenya

2Kenya Nutritionists and Dieticians Institute and Department of Nutrition and Health, Maseno University, Department of Nutrition and Health, Maseno University, Maseno Township, Kenya

3Department of Biomedical Sciences, Maseno University, Maseno Township, Kenya

Correspondence to: Omondi D. O., Kenya Nutritionists and Dieticians Institute and Department of Nutrition and Health, Maseno University, Department of Nutrition and Health, Maseno University, Maseno Township, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

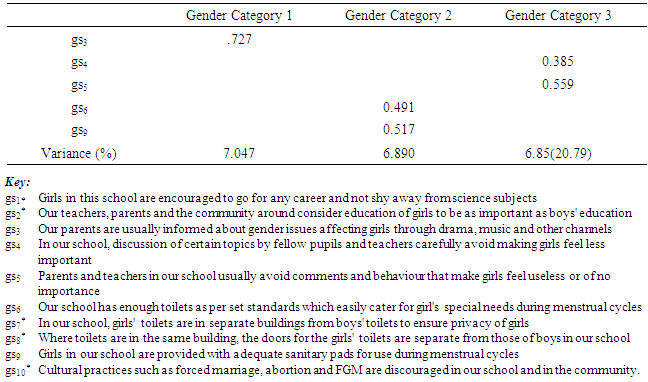

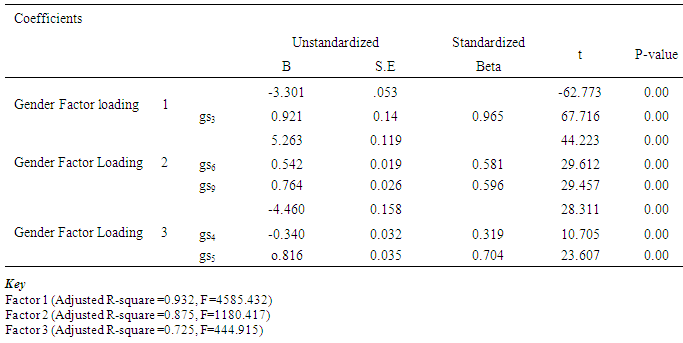

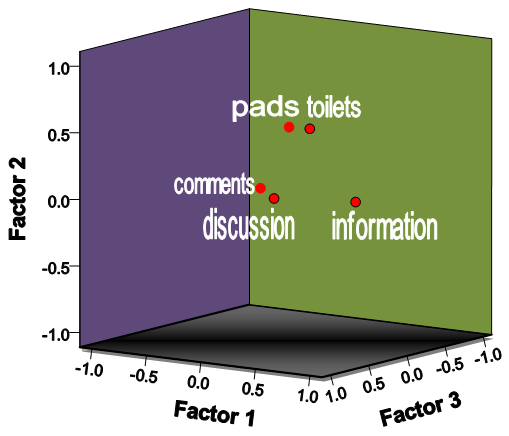

Background: Low school completion rates for girls could be attributed to gender stereotypical biases and preferential treatments usually accorded to male as opposed to female gender in the education system. School health policies have been rolled out in primary schools in Kenya to ensure equity among boys and girls. However, girls still face challenges related to gender issues than boys. This study explored the extent of implementation of gender perspectives in school health policy for primary schools in Usigu division. Materials and Methods:The study was conducted in rural primary schools along the beaches in Usigu Division using cross-sectional analytical design. A sample of 338 girls selected through stratified random sampling, from STD 4-8 was used. Data was collected using structured questionnaires, analysis done using descriptive and inferential statistics mainly hierarchical regression with Principal Axis Factor Analysis Techniques. Results: Implementation threshold of gender policy as perceived by the STD 4-8 respondents (girls) was 20.79% of total variance explained by the three different gender factor loadings based on principal factor axis factoring. Gender factor loading 1 made up of one item,“Our parents are usually informed about gender issues affecting girls through drama, music and other channels” which explained a variance of 7.05% of the gender implementation was the most implemented, followed byGender factor loading 2 with a variance of 6.89%and made up of two implementation indicators: “Our school has enough toilets as per set standards which easily cater for girl's special needs during emergency menstrual cycles” and “Girls in our school are provided with adequate sanitary pads for use during menstrual cycles”. Gender factor loading 3followed very closely with a variance of 6.85% and constituted two items: “In our school, discussion of certain topics by fellow pupils and teachers carefully avoid making girls feel less important” and, “Parents and teachers in our school usually avoid comments and behavior that make girls feel useless or of no importance”. Conclusions: The findings revealed that level of implementation of the gender component of the current policy is still weak based on 50% factor loading out of 10 elements drawn from the policy. The study however, recommends that more evaluations focusing on the broader themes of the policy should be conducted in the wider contexts and further explorations be done to explain non extraction of other factors.

Keywords: Gender perspectives, School health policy, Primary school girls

Cite this paper: Otiato S. O., Omondi D. O., Abong’o B. O., Gender Perspectives in School Health Policy Implementation among Girls in Usigu Division Primary Schools, Siaya County, Kenya, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 49-55. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20160602.02.

1. Introduction

- Despite call for gender equity, episodes of inequalities continue to be manifested in diverse socio-cultural contexts including schools, sometimes in conspicuously explicit occurrences and sometimes in extremely 'silent' forms. Regrettably, schools ought to be neutral grounds for imparting and promoting correct value and belief systems in school children for the development of an egalitarian society. But as Gramsci (1994) observes, the problematic aspect of the school as an institution is that rather than perpetuate equity between boys and girls, it instead serves as an agent of dissemination of the hegemonic ideologies such as gender and patriarchy which are embodied in the curricular in both the formal and the hidden forms. Patriarchy constitutes structural arrangements that initiate, support and legitimize the view that women and hence girls should be oppressed, devalued and dominated by men or boys. It is in fact an ideology anchored on the systematic oppression of women by men and the supremacy of men (or boys) over women (or girls) which enables the former to dominate the latter (Hartmann, 2002). Interestingly, where that ideology is encouraged, over time, it becomes easier to obtain that supremacy primarily by consent rather than by coercion, by moral and intellectual leadership rather than by domination, which in essence constitutes hegemony (Christie, 2008).A study conducted by Verveer (2011) recognized that wide disparities exist between boys and girls and showed that if schools were to achieve the wider goal of maximizing learning for both boys and girls, then they ought to provide gender-neutral teaching materials, update books and curriculums so that teaching materials do not depict girls and women only in traditional roles, encourage girls to try different lines of work and to participate more broadly in society and recruit and train more female teachers. Although this view elucidates the glaring gaps between male and female gender in schools particularly on curricular and pedagogical issues, it is nevertheless important to point out that gender gaps in schools are not only restricted to biases through ideological beliefs or curricula materials and methods, but also socio-economic issues such as nutritional status. Based on this background, this study explored gender perspectives of school health policy for primary school girls in Usigu Division in Siaya County, Kenya. The study sought to evaluate implementation of gender perspectives as prescribed in the Kenya National School Health Policy (2009).

2. Materials and Methods

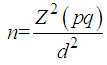

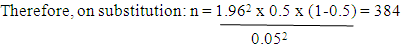

- The study adopted a cross-sectional analytical design. Data was collected within a period of one month and analyzed once for the period. This design was chosen because it does not allow for any manipulation of factors and provides population characteristics as they are at one point in time. The study population consisted of 1531 eligible girls then enrolled in STD 4-8 in primary schools in Usigu division. Sampling unit was an eligible girl pupil. A sampling frame based on the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria was developed and a representative sample size determined.Sample size was determined according to Fisher et al (1991), using the formula;

Where: n = minimum sample size (for population >10,000) required.Z = the standard normal deviate at the required confidence level, (set at 1.96 corresponding to 95%, Confidence level adopted for this study).p = population proportion estimated to be girls in Usigu which now stands at approximately 50% q = 1-pd = the degree of accuracy required (was set at 0.05)

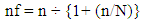

Where: n = minimum sample size (for population >10,000) required.Z = the standard normal deviate at the required confidence level, (set at 1.96 corresponding to 95%, Confidence level adopted for this study).p = population proportion estimated to be girls in Usigu which now stands at approximately 50% q = 1-pd = the degree of accuracy required (was set at 0.05) However, since the targeted population was 1531eligible pupils which are <10,000, the final sample size (nf) was adjusted as follows:

However, since the targeted population was 1531eligible pupils which are <10,000, the final sample size (nf) was adjusted as follows: Where; n f= desired sample size (when target population is less than 10,000) n = desired sample size (when target population is greater than 10,000) N = the desired sample size (target population)nf = 384 ÷ {1+ (384/1531)} =338 (plus 10% expected non-response) Stratified random sampling technique was used to select pupils to be included in the study. Schools were stratified into either public or private before randomly selecting girls proportionately according to sample size. Sampled schools were visited one week before the actual data collection and children were issued with consent forms which their parents or guardians were to sign showing their approval for their children to participate in the intended research. The forms were to be returned on the actual day of data collection and any child whose parents did not consent or who personally did not assent to participate in the study was excluded.The children were responded to questions after reading out the questions loudly alongside the expected responses for each child in confidence and a language that was perceived to be understood by all the respondents and coding their responses appropriately.Measurement of variables focused on 10 key indicators drawn from the school health policy tested using a 5-point likert scale ranging from 1-strongly agree and 5=strongly disagree. Dependent (outcome) variables were all possible gender categories as perceived by girls based on factor loadings within gender framework in school health policy measured by the ten indictors generated from policy guidelines (2009). Independent variables focused on single indicators of gender perspectives of school health policy. Analysis adopted use of descriptive and inferential statistics mainly hierarchical regression with Principal Axis Factor Analysis techniques to show the relationship between the factor loads (which depicted opinion agreement on gender areas being implemented) and key isolated gender policy guideline measures. Factor extraction zeroed in on Varimax rotation and Eigen values equivalent to 1.

Where; n f= desired sample size (when target population is less than 10,000) n = desired sample size (when target population is greater than 10,000) N = the desired sample size (target population)nf = 384 ÷ {1+ (384/1531)} =338 (plus 10% expected non-response) Stratified random sampling technique was used to select pupils to be included in the study. Schools were stratified into either public or private before randomly selecting girls proportionately according to sample size. Sampled schools were visited one week before the actual data collection and children were issued with consent forms which their parents or guardians were to sign showing their approval for their children to participate in the intended research. The forms were to be returned on the actual day of data collection and any child whose parents did not consent or who personally did not assent to participate in the study was excluded.The children were responded to questions after reading out the questions loudly alongside the expected responses for each child in confidence and a language that was perceived to be understood by all the respondents and coding their responses appropriately.Measurement of variables focused on 10 key indicators drawn from the school health policy tested using a 5-point likert scale ranging from 1-strongly agree and 5=strongly disagree. Dependent (outcome) variables were all possible gender categories as perceived by girls based on factor loadings within gender framework in school health policy measured by the ten indictors generated from policy guidelines (2009). Independent variables focused on single indicators of gender perspectives of school health policy. Analysis adopted use of descriptive and inferential statistics mainly hierarchical regression with Principal Axis Factor Analysis techniques to show the relationship between the factor loads (which depicted opinion agreement on gender areas being implemented) and key isolated gender policy guideline measures. Factor extraction zeroed in on Varimax rotation and Eigen values equivalent to 1. 3. Results

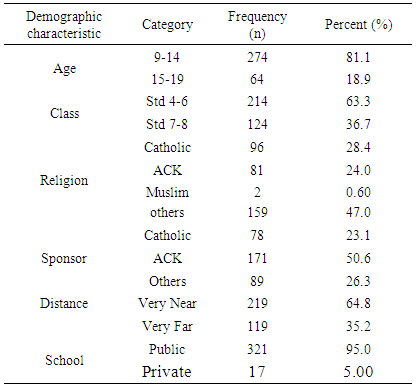

- Data was collected on selected demographic characteristics which included respondent’s sex, age, class and religion. Other important characteristics included the sponsor of the respondent’s school, distance of the school from the lake and school category. The demographic characteristics were summarized in Table 1.

|

|

| Figure 1. Graph showing factor plots in rotated factor space |

|

4. Discussion

- This study has identified three critical factors in gender policy implementation with a total of five gender indicators drawn from the school health policy guidelines passing approval test by the girls. These critical indicators had a focus on parental awareness, girl child support through basic necessities like sanitary towels and toilet facilities for emergency menstrual cycle. The last two aspects focused on teacher and parental gender sensitive comments. Parental awareness seems to be the focus on gender issues related to school health policy. This is evidenced by continuous information flow to parents through media, role play and drama. Some authors argue that earlier exposure to what it means to be a male or female comes from parents (Laucer and Laucer, 1994; Santrock, 1994; Kaplan, 1991). This means that targeting parents would be appropriate in ensuring proper implementation of school health policy. However, despite this knowledge parental focus still accounted for just a small fraction towards successful implementation of the school health policy. Ensuring that safety sanitary measures are put in place somehow received girls’ approval. As second best gender factor loading, it appears that schools were implementing gender issues focusing on sanitary pads and adequate toilet facilities to ensure safety of girls during emergency menstrual cycle. WHO (2012) in Kyalo, P and Wambuyu, M.P (2014) emphasized access to sanitary activities as fundamental right that safeguards health, humility and dignity. Girls’ approval of critical components of sanitation and safety was a clear demonstration of efforts made towards implementing gender issues picked from the school health policy within framework depicted by gender factor loading 2. Although items under Gender factor loading 2 were significantly fairly predictive of adequacy of toilets or sanitary pads, the other two closely related items which sought to demonstrate that sanitary facilities should not only be adequate but also girl- friendly, by either being in separate buildings (gs7) or having separate doors for boys and girls (gs8), failed to meet girls’ approval threshold and were therefore not extracted. This could be a pointer to the fact that it was not a common practice for schools in the study area to have girl-friendly sanitary facilities in which girls’ toilets were separate from boys’ or with different doors for both genders. Since as (Mensch et al., 1998) observed, such poor quality sanitary conditions may have different implications for girls regarding their special needs during menstrual periods as well as their vulnerability to sexual harassment on their way to and from the toilets while at school, non extraction of the two items could justify the fact that sanitary facilities in the study area were indeed not girl-friendly. As (Birdthistle, 2010) noted, in girl-friendly schools, boys’ and girls’ toilets are not only separate for privacy but also ensure that other essential supplies for menstrual management are provided. Supposing that schools were compliant to this prescription, one would expect a different scenario in which these iterations were extracted with a big coefficient of variation (R-square) but that was not the case. The third emerging gender factor loading 3 had a focus on sentiments and comments that are gender sensitive from topical discussions by pupils, teachers and parents. This domain has received scrutiny by number of authors. Ogunbanwo (1998) study explored gender stereotyped beliefs and perceptions of teachers in classroom practices and found out that teachers held more positive beliefs with males than with female gender. Gupta and Yin (1990) arguing that school texts are a major agent of socialization while examining the representation of males and females in two English basal texts, showed that inequities existed in schools and were evidenced by depicting males in exciting situations only in which males were shown as possessors and females, possessed; Boys were shown in active behaviour, girls in passive.Mutekwe and Modiba (2004) study which explored manifestations of gender insensitivity in Zimbabwean school curriculum reported that whereas teachers contributed to the development of gender sensitivity in the school curriculum by disseminating sexist gender role biases and patriarchal ideologies and stereotypes, girls concurred that boys tend to dominate numerically in the subjects traditionally stereotyped as masculine such as Mathematics and Mental Sciences while girls dominated numerically in subjects associated with domesticity such as Food and Nutrition, Fashion and Fabrics. This is consistent with the views of (Stangor & Lange, 1994) who describe men as intellectually competent, strong and brave while women are perceived to be homely, warm, incompetent and passive. They portray the male as a strong dominant person with leadership trait, one who should work outside the home often in prestigious occupations, while female is usually portrayed as being subordinate and confined to the home. Confirming these stereotypical tendencies, (Ogunbanwo, 1988 & Erinosho, 1997), noted that whereas females were portrayed in ‘less superior’ careers such as traders, hairdressers and secretary, males were depicted in skillful professions like doctors, scientists and engineers. This view is also supported by the observation that in many schools, many teachers still operate with the preconception about skills, behavior and performance of pupils based on their gender (Sadker & Sadker, 1982).Despite the efforts being made to address gender gaps in school, it is apparent from these findings that a lot more could still need to be done to address gender stereotyping at school. This is because teachers, who ought to be agents for restoring equilibrium between different genders, may encourage students to pursue domestic curriculum and a few women to take mathematics and sciences or still, because of teachers’ biased attitudes, girls may have to fight several pressures including racism, sexism and patriarchy in school (Grown & Sebstand, 1989). In fact, it has been observed that teachers and curriculum in general reinforce social biases and discrimination practices against women or girls through the content and the method of teaching employed in schools and noted that girls spend more time in fetching water, cleaning classroom than they spend on the educational activities than boys (Subrahmanian, 2002). But, as pointed out by (Mensch & Llyod, 1998), schools in which boys are favoured in class, provided with a more supportive environment, left free to harass girls, in which girls’ experience of unequal treatment is not recognized by boys and where Maths is taken less seriously for girls, discourage girls’ retention and in those circumstances, girls are more likely to drop out of school prematurely and are less likely to excel at end of standard eight exams. They observed that teachers often use adjectives such as 'weak', ‘lazy’, and ‘blind’ to characterize the girls in the classroom and noted that teachers had little preference for teaching girls as compared to boys.While concurring with this assertion, a few other studies in Nigeria have shown that educational system not only reinforce traditional gender roles but are also agents of stereotyped attitudes towards gender stereotypes. For example, Adoyeji (2010) study which explored the gender stereo-typed beliefs and perceptions of secondary school teachers in classroom practices, revealed that most secondary school teachers are largely aware of the gender stereotyped beliefs and must hence learn to recognize and eliminate gender biases in their student-teacher interactions within and outside their classrooms, avoid language that limit one gender or another from participating in classroom interaction and select gender neutral educational materials and texts for use to combat bias. In another related study, Aladejana (2002) found that Nigerian science curriculum for junior secondary school contains more activities that favour boys than girls creating gender inequality in learning in classroom. On their part, Oseji and Okola (2011) have also shown that boys are more favoured to attend school in rural Nigeria than girls due to cultural norms, and incentives and subsidies are recommended to be in introduced in order to boost enrolment of girls. These views explain why schools could be important settings for ensuring equity between male and female genders.Noting that the other items on the importance attached to the education of girls and non-discriminatory practices linked to their career goals were not extracted, it can be argued that their relative docility in the factor exploration process could be a testimony for the existence of stereotypical biases held by teachers and parents towards girl-child education. Ideally, “girls should be encouraged to go for any career and not to shy from any science subject” (gs1) and “parents, teachers and community ought to attach equal importance to boys’ education as well as girls’ ” (gs2).Unfortunately, their non extraction depicts girls as growing up or learning in hegemonic and patriarchic social contexts in which the males are superior and that may allow them to dominate and be given preferential treatment on critical aspect of education (Jacobs & Bleeker, 2004; Camp, 1997; National Science Foundation, 2000). This is contrary to provision of Article 10 of the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 1981) in America which decrees that all state parties should take appropriate measures to ensure the same conditions for career and vocational guidance for both girls and boys in the field of education. When such ideological discrepancies permeate the education system, parents and teachers discriminately allocate the limited education resources and opportunities on the basis of gender with boys having greater odds of accruing more privileges. This tendency has been clearly represented by (Aslam, 2007a) when he argues that in many instances, parents in Pakistan select comparatively better schools, in the context of fees, for their sons while daughters are ignored or enrolled in schools having non or fewer facilities.In conclusion, the findings revealed that level of implementation of the gender component of the current policy is still weak based on factor loadings as approved by girls. The study however, recommends that more evaluations focusing on the broader themes of the policy should be conducted in the wider contexts and further explorations be done to explain non extraction of other factors. Inclusion of boys opinion would be necessary.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML