-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2015; 5(4): 119-133

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20150504.03

Neighborhoods and Social Interactions: The Case of Al-Najada Area in Doha

Bassma Eissa , Rana Awwad , Reem Awwaad , Raffaello Furlan

College of Engineering Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Correspondence to: Raffaello Furlan , College of Engineering Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Cities provide places for people to live, work, learn and socialize. As urban environments, cities nowadays are typically characterized by urban sprawl in which open public spaces (1) are neglected and/or (2) social interactions are discouraged. In fact, the encouragement of social interactions among neighbors is a vital factor implementing livability among city dwellers. Recent evidence suggests that social interactions occur infrequently in contemporary urban neighborhoods. Therefore, it is worth investigating how communities can be designed in the future with the aim to increase social interactions. Al-Najada area in Doha provides a useful case study because it is a traditional area, built based on formal social structures aiming to the formation of social interaction in old neighborhoods (which is called Fereej in Arabic). This paper investigated how the urban fabric of Al-Najada area can be implemented in order to enhance social interactions and become an effective sample of sustainable development. Also, this paper examined the factors that contribute to socially sustainable development in the regeneration of Al-Najada as a traditional asset in the heart of Doha. Literature review is conducted on topics of sustainable urbanism, urban sociology, and built heritage to learn about design implementation in order to enhance social interactions within the urban fabric of neighborhoods. Therefore, content analysis, site observations, and walking tour assessments are adopted as the main research methods in order to investigate how social interactions at Al-Najada area can be encouraged, namely how the spatial form can be implemented in order to enhance social interactions. The research study findings led to the definition of a set of recommendations for a design approach, based on smart planning and design guidelines, aiming at implementing Al-Najada neighborhood in order to facilitate social interactions. The recommendations are genuinely plan-led, empowering local people to shape their surroundings, with concise neighborhood plans setting out a positive vision for the future of Al-Najada area.

Keywords: Sustainable Urbanism, Social Interactions, Al-Najada, Doha, Traditional Neighborhood

Cite this paper: Bassma Eissa , Rana Awwad , Reem Awwaad , Raffaello Furlan , Neighborhoods and Social Interactions: The Case of Al-Najada Area in Doha, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 119-133. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20150504.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Neighborhoods are the source of dynamic growth of cities. People tend to structure their neighborhoods according to their cultural and social needs. In the Gulf region, the neighborhoods design proves this cultural connotation where the fereej is the core place for social interaction and bonding (Jaidah, and Bourennane, 2009). Nowadays, globalization and modernism forces have greatly affected neighborhood designs that discourage social interactions. At present, neighborhoods within Doha are not pedestrian-friendly and do not support sustainable development aspects. Al-Najada area is a significantly traditional area in the heart of old Doha. The significance of its history, location, architecture and people makes it worth studying to preserve it for future generations through implementing it as a livable neighborhood for social interactions.With the aim to regenerate Al-Najada area and implement it for social interactions and sustainable growth, the paper is developed on the crux of sustainable development aspects. It aims to investigate the urban fabric and its social connotations of Al-Najada area, which is one of the few districts in Doha that contains treasurable remains of traditional houses along with Al-Asmakh area and Souq Waqif area. This included an overview about the area’s history to explain the evolution of Al-Najada throughout the years. Accordingly, a comprehensive study about Al-Najada from different aspects is presented with a major focus on the social aspect; location, land use, architectural style, accessibility, open spaces, and the public realm are the main aspects of the study. To achieve this, relevant literature works are reviewed to acquire knowledge on three main disciplines: sustainable urbanism, urban sociology, and built heritage. Site observations and walking tour assessments are used in conducting this research. Also, investigation of the previous literatures is conducted in order to overlook the studied area with relevant recommendations and design guidelines.In the context of this research study and relevant to its questions, the following investigation focuses on the major objectives that serves the research’s outcome. The first major objective deals with the evaluation of the current social aspect within the studied area and investigating different methods to improve the social connectivity between users. The second objective is related to assessing the urban spatial form that supports and boosts social activities and interactions through a set of recommendations and design guidelines.

| Figure 1. Location Map of Al-Najada Area in Doha, source: Google Maps |

2. Background

2.1. Historical Overview

- Life in Qatar, even before the collapse of the pearl market in the 1930s, was marked by widespread poverty, malnutrition and disease prior to any emergence of local architecture (Jaidah, and Bourennane, 2009)The arrival of oil prospectors and the establishment in 1935 of Petroleum Development Qatar signaled the beginning of a challenging new world. Although not huge in comparative terms, the oil revenue instantly turned the tiny, impoverished population into one of the richest per capita countries in the world. Qatar’s first school opened in 1952 and a full scale hospital followed in 1959, marking the beginning of long-term investment in the country, most importantly the cultural heritage of Qatar was dominant, such as residential houses, palaces, and public areas.In the 1950s, a number of new buildings have been constructed. The housings of this period formed a significant percentage of construction, along with the beginnings of the infrastructure construction – roads, drainage, sewerage, electricity and water distribution (MDPS, 2014). But it was housing that gave ordinary Qataris the opportunity to develop their construction and management skills while developing the economic basis of the country as they produced housing both for themselves as well as for the increasing numbers of foreigners. This was a period that saw a number of buildings constructed, mainly around the outer ring of Doha, without effective controls on either their designs or construction, and in a variety of styles but all based on a reinforced concrete frame construction with concrete block infill. The inner ring of Doha, as well as the smaller settlements around the peninsula, was left more or less as they had been for decades with no significant constructions due to a lack of a comprehensive plan for development or redevelopments.

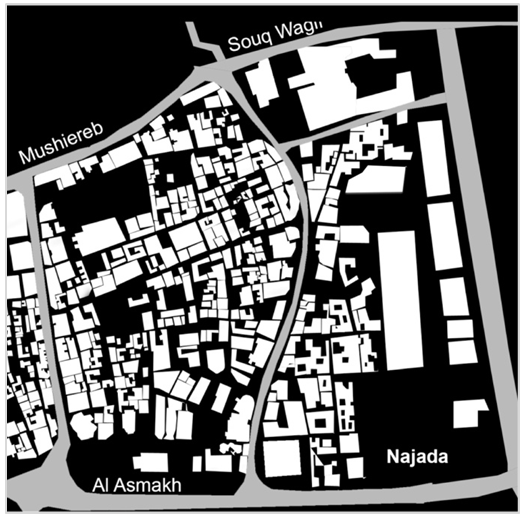

| Figure 2. Figure-Ground Map of Al-Najada showing its Urban Massing, source: Photoshped Google Map |

2.2. Physical Aspects of Al-Najada Area

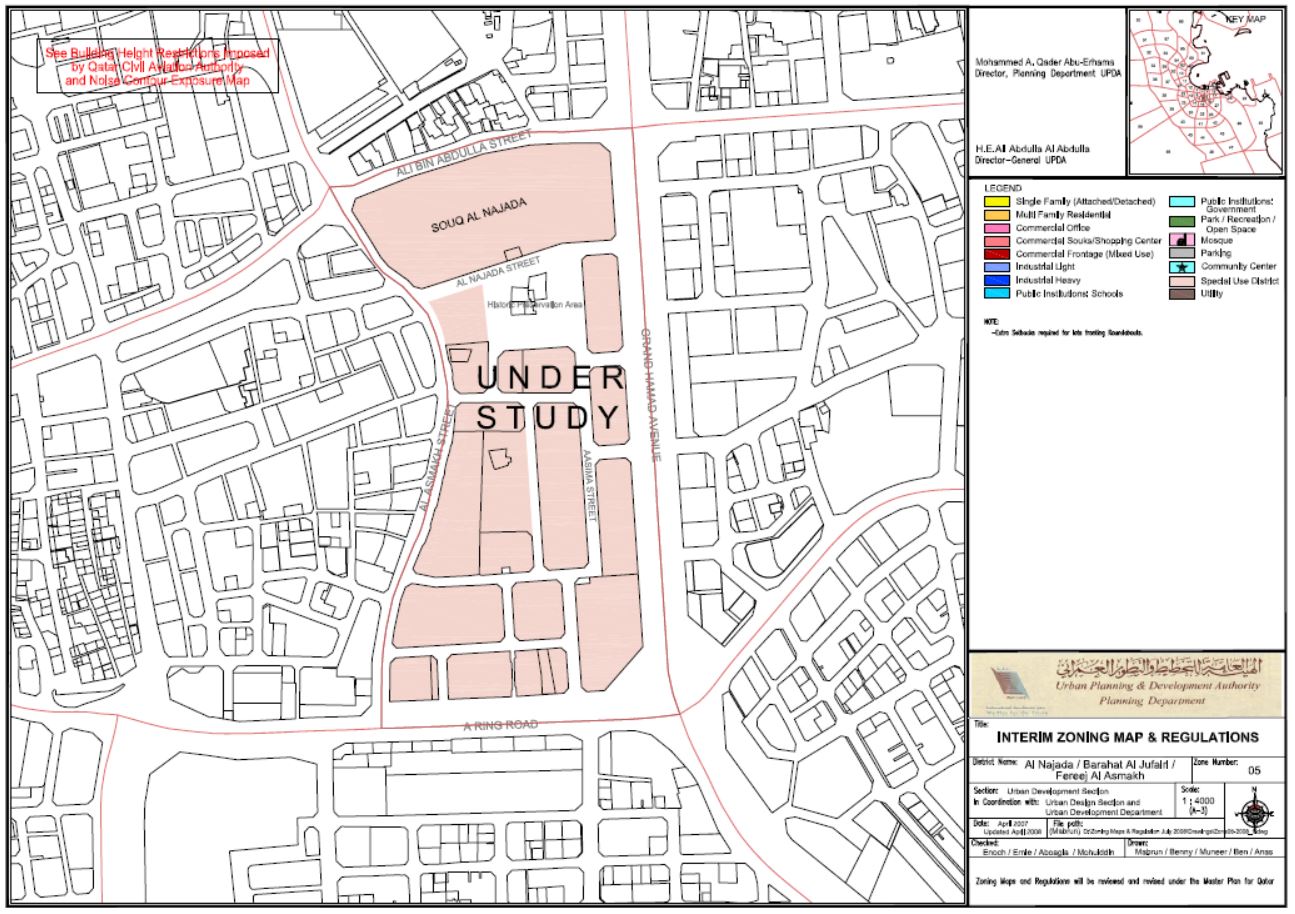

- Al-Najada is one of the major remains of the old city of Doha in Qatar, surrounded by the most attractive retail area of Souq Waqif and the emerging project of Musheireb Downtown. Approximately, it has a total area of 186,517 square meters (MDPS, 2014). According to the administrative division of the State of Qatar, the zone of Al-Najada (zone number 5) is located within the municipality of Doha. The current land use varies between residential, commercial and open spaces with no future plans for the area as it is considered “under study” based on the latest land use map generated by the Ministry of Municipality and Urban Planning (MMUP).The house is the smallest urban unit in the socially generated urban pattern of al-Najada. The courtyard, which forms the heart of the family life is open to the sky and provides a source of ventilation and daylight. It was also considered as a private space where domestic activities were carried out. Certain coastal examples of Qatari vernacular architecture suggest that their builders either came from Iran or were influenced by its architecture. Similarities are seen to exist between Arabian Gulf architecture, the main difference being due to the amount of finance available for construction (Richardson, Bae, and Baxamusa, 2000). In contrast the builders of houses within Doha were influenced more by the architecture of Najd.The modern architecture can be also observed in some of the buildings at the parameters of Al-Najada includes commercial and retail activities. As of the current condition of area, the lack of proper maintenance of its buildings is obvious in addition to the huge percentage of these buildings in poor condition. Also the old urban fabric of Al-Najada is neglected. Being located at the old center of Doha, Al-Najada area can be easily accessed especially with having it surrounded by four main streets; Ali Bin Abdullah Street (North), Grand Hamad Avenue Street (East), A-Ring Road (South) and Al Asmakh Street (West). It has also a number of internal streets that facilitate the access to the different plots within the area. The major issue in relation of the accessibility in the current condition of this area is the congestion resulted from the lack of planning and the construction works in the surrounding sites. The area lacks the availability of public spaces. Many old buildings were demolished to provide parking spaces for the residents, workers and visitors of the area. Al-Najada Park located at the North-Eastern part of the area is the main and most crowded intersection situated at the street corner which is surrounded by towers such Al-Fardan tower, similarly this park is a continuous link to the traditional context of Al-Najada. The park doesn’t have a significant style, but mostly is seen as a mix between a traditional and modern park. Modern in the context that it consists a lot of green areas with trees and flowers. The park is mostly attracting the migrant workers who live and work in this area which exemplified in Al Najada and Al Asmakh streets. Groups of people are also gathered in the existing park (Barahet Al Jufairy), in intersection points of the secondary streets and space that is surrounded by different types of shops.

3. Literature Review

- The background on the topic of traditional urban fabrics and sustainable development is related to cultural and social norms in multicultural societies in the Gulf region. In the context of this research study and relevant to its objectives, the topic was investigated from the perspective of three main disciplines: sustainable urbanism, urban sociology, and built heritage. These disciplines are identified by default since they tackle major issues in the field of sustainable development in traditional urban fabrics.

| Figure 3. Land Use of Al-Najada Area as of 2008, source: MMUP Planning Authority |

3.1. Sustainable Urbanism

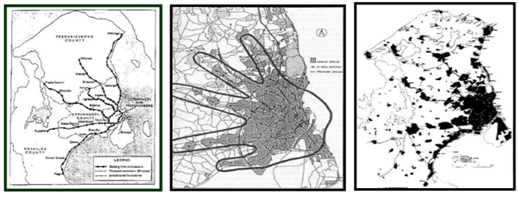

- Contemporary literature on sustainable development has emphasized on the importance of social aspects of urban environments (Farr, and Hoboken, 2008). Urban settlements and buildings are founded upon social interactions (Saleh, 2002). In essence, the concepts of social sustainability and urban sociology, according to Saeidi and Oktay, are fundamental human concepts that are grounded on sets of relationships that order and define the status of individuals in relation to society (2012). An interesting paper on the discipline of sustainable urbanism has reviewed and discussed the various approaches to sustainable urban development (Hassan and Lee, 2015). In their paper, Hassan and Lee have reviewed 10 topics that are highly relevant to sustainable urban development (SUD): a balanced approach to SUD, socio-cultural awareness, urban sprawl, economic urban development, transportation, urban renewal, mitigating greenhouse gases, urban vegetation, assessment systems, and city structure and land use (Hassan and Lee, 2015). The critical reading of the relevant publication on the topic is the main method used. Their analysis showed that Asian countries, especially China, are making changes towards SUD more than nations of other continents (Hassan and Lee, 2015). The main finding concludes that transportation is the most prominent challenge in the field of SUD, followed by socio-cultural awareness (Hassan and Lee, 2015). Thus, transportation should be the starting point for attaining SD in urban areas. According to them, researchers who have addressed the need for SUD around the world have reached a consensus that transportation policies can help create urban sustainability (Hassan and Lee, 2015). Similarly, transit oriented development (TOD) is one of the emerging aspects that define sustainable urbanism (Haag, and Lagunof, 2004). Another remarkable paper on “Public Transport and Sustainable Urbanism: Global Lesson” by Robert Cervero, defines TOD as a viable model for transportation and land-use integration in many rapidly developing cities of the world (Cervero, 2014). According to Cervero, TOD can be defined in a simple concept as a concentration of a mix of moderately dense and pedestrian-friendly development around transit stations to promote transit riding, in order to increase walking and cycling. His paper focuses in its framework on Asian cities that have historically been transit oriented, featuring mixes of land uses, plenty of pathways for pedestrians and cyclists, and sufficient transit services on major roads. However, recently, these cities have changed to meet the global demands occurred in the last century in car ownership (Cervero, 2014). Globally, TOD is more developed in Europe, and in particular Scandinavia. It is note-worthy that step-one in bringing TOD from theory to reality is the formulation of a vision and conceptual image of the future metropolis, such as the celebrated “Finger Plan” of Copenhagen in Denmark that is illustrated in Figure 6 (Cervero, 2014). The figure reveals the evolution of Copenhagen from a Finger Plan, to a directed rail-investment program along defined growth axes, to finger-like urbanization patterns. Cervero also pointed out that public interventions are a necessary ingredient of successful TODs. In this respect, global experiences demonstrate that leadership, combined with forward-looking urban planning and efficient pricing of scarce resources; provide the necessary complements to make TOD a viable and sustainable form of urbanism.

| Figure 4 |

| Figure 5 |

| Figure 6 |

3.2. Urban Sociology and Social Sustainability

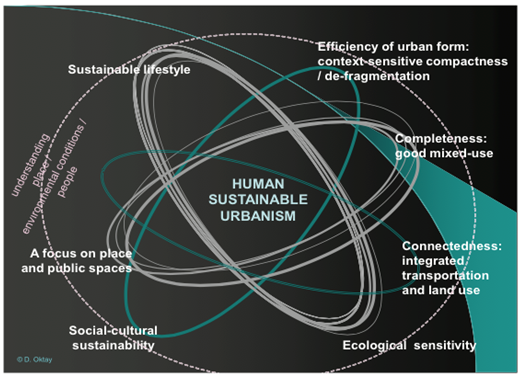

- At a time of uncontrolled globalization, there is an urgent and a demanding need for a major transformation towards a holistic strategy for sustainable urbanism in cities worldwide (Al-hagla, 2010). The matter of sustainable urbanism and social sustainability is widely discussed in the paper entitled “Human Sustainable Urbanism: In Pursuit of Ecological & Social-Cultural Sustainability”, by Derya Oktay, as he calls for sensitivity to the traditional urbanism and impact of global ideas, practices and technologies on local social and cultural practices. It is essential to point out that changes which have taken place in the world over the past twenty years have produced cities that are not just chaotic and uninteresting in appearance, but have serious environmental problems threatening their inhabitants (Oktay, 2012). Throughout the paper, the author has provided a theoretical framework of defining sustainable urbanism, which includes three different movements: sustainable development, the new Urbanism, smart growth, and green architecture (Oktay, 2012), and a critical review of its philosophical and practical background. In addition to assessing the emerging contemporary approaches to sustainable urbanism and analyzing the mentioned case study exemplified in the traditional Turkish (Ottoman) City. The produced framework by the author has proposed a holistic structure for sustainable urbanism that incorporates environmental sustainability with social sustainability as shown in Figure 7. Also, Oktay suggested a mechanism of a sustainable community, which endeavors to promote multi-functional rather than mono-functional settlement patterns by providing compact urban behaviors, with a broad range of services and amenities in close proximity. This reduces the need for vehicular and public transport, thereby decreasing demands on infrastructure and energy resources, while promoting pedestrian accessibility and community.

| Figure 7. Copenhagen’s Figure, source: Cervero 2014 |

| Figure 8. A Holistic Framework for Human Sustainable Urbanism |

3.3. Built Heritage and Preservation

- The reviewed literature on the discipline of built heritage presents specific investigations on the value of traditional districts of the city, which proved to be sustainable (Nasser, 2003). In their paper on “Sustainable Development and the Rehabilitation of a Historic Urban District”, the authors examine the attributes and factors that contribute to socially sustainable development in the rehabilitation of historic districts in China (Yung, Chan, and Xu, 2014). They have identified social sustainability factors as contributing to the rehabilitation of historic districts. The important factors are: maintain good physical condition to fulfill educational role, provide public involvement opportunities, enhance sense of place and local culture, enhance cultural identity and collective memory, and retain significant meanings and associations to the community (Yung, Chan, and Xu, 2014). Their resulting framework is considered a good reference to examine other sensitive heritage sites worldwide. The main finding of their paper is that rehabilitation of historic urban districts should be made more sustainable through a better understanding of the social dimensions, in order to contribute positively to avoiding the eviction of poor tenants and owners and the destruction of the community’s social fabric. Another research paper entitled “Non-Destructive Techniques as a Tool for the Protection of Built Cultural Heritage” focuses on the recent technological developments in the field of non-destructive techniques in the field of built cultural heritage protection in cities. The work in this paper discusses the use of Digital Image Processing (DIP), Infrared Thermography (IRT), Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), Ultrasonic (US) testing, and Fiber Optic Microscopy (FOM) for the diagnosis of decay and assessment of conservation interventions, and the results are processed with Computer Aided Design (CAD) software and Geographical Information Systems (GISs) in order to support strategic planning of the conservation interventions on monument scale and environmental impact assessment for the protection, management and sustainable development of built cultural heritage of a city. (Moropoulou, Labropoulos, Delegou, Karoglou and Bakolas, 2013). In essence, another paper entitled “Correlations between Public Appreciation of Historical Building and Intention to Visit Heritage Building Reused as Retail Store” focused on the appreciation of the reuse of the old and historical buildings as retail spaces by analyzing two variables: appreciation of the historical buildings, and the visitors’ behavior through a quantitative research conducted in Bandung in Indonesia (Adiwibowo, Widodo, & Santosa, 2015). The paper showed that treating the historical buildings as tourism objects is the most common way that helps in building the public appreciation and maintain the buildings existence. Other studies concluded that the preservation of the building exterior attracts the visitors to enter the retail stores within (Tweed and Sutherland, 2007). It was also found that the more additions to the buildings the more negativity the perception of the building façade would be. Therefore, we find that historical buildings with minimum changes and alterations to their exterior can be considered as a value in adaptive reuse as retail especially that we can say that the public still care about the existence of these buildings (Herzog and Shier, 2000).In brief, it is noted from the reviewed literature that sustainable development strategies are achievable from the social dimension (Glanz, 2011). This is because it supports strong, vibrant, and healthy communities by creating a high quality built environment, with accessible local services that reflect the community’s needs and social and cultural well-being. Consequently, a place that supports and encourages social interactions is said to be highly sustainable (Lynch, 1960). Also, since the studied area is historical, the appreciation factor for the buildings is associated with the public evaluation of the façade as the building exterior facing the public street (Goulding, 2001). The color, building material, and proportion elements of the façade should be considered in evaluating any building esthetically. The emotional factor has an important role in the evaluation of historical buildings by the visitors as the perception of the environment affects firstly the mood and then the people behavior (Nasar, 1983). As understood from the literature, in order to achieve sustainable development, economic, social, and environmental gains should be sought jointly and simultaneously through the planning system. The planning system should play an active role in guiding development to sustainable solutions (Gamba, 2011). This indicates that sustainable development should be an integral part of planning, especially historical districts that are built responding to social needs, as what Al-Najada area used to be. In brief, it is noted from the reviewed literature that sustainable development strategies are achievable from the social dimension. This is because it supports strong, vibrant, and healthy communities by creating a high quality built environment, with accessible local services that reflect the community’s needs and social and cultural well being. This is reflected on the case of Al Najada area, as the social dimension is achieved through different social settings which are provided unintentionally within the context, however it is restricted to a certain group of people exemplified in migrants communities. Consequently, the literature refers to the idea of ‘Sustainable Places’ that support and encourage social interactions among its users. However, the resulted interactions ought to satisfy the variation of ethnic backgrounds, which is absent in the case of Al Najada. Despite the fact that Al Najada is placed in the oldest neighborhoods in the heart of Doha, it promotes a multi-functional settlement patterns, and that is what makes Al Najada area is unique in its urban settings. The close proximity of the different functions and services ease the creation of a successful TOD system in the studied context, which counted to be one of the major confronts in the area. It is well understood from the reviewed literature that the obvious reliance on cars in the neighborhoods discourages walking and cycling while the opportunity for rich community life is being lost, and this exactly what outlines Al Najada area, as the dependence on motorized vehicles is dominantly expanding and this negatively affects the urban quality of the area.When it comes to built heritage and cultural perseveration, Al Najada area celebrates the largest percentage of authentically traditional structures dated back to 1930’s. The appreciation factor for the buildings is associated with the public evaluation of the façades facing public streets. The current misuse, which has exerted on the studied area, has led to the lessening the traditional significance and weakening the local identity. It is noticed that the Lack of public awareness of the preserved heritage value and the misconception of practice by the migrant individuals are the major causes of weakening the local existing treasures placed in the area for more than 80 years. Recently, the area has gapped the attention of the government and the local authorities, which focused on preserving built heritage in several cities around Qatar, including Al Najada and the surrounding neighborhoods. Furthermore, the planning system should play an active role in guiding the development through sustainable solutions in terms of economic, social, and environmental expansions, which should be sought jointly and simultaneously through the planning system. This indicates that sustainable development should be an integral part of planning, especially historical districts that are created responding to social needs and individual preferences, as what Al-Najada area used to be in the early establishment of its built environment.

3.4. Theoretical Framework of the Study

- From the discussion presented earlier, the main objective of this research study is to investigate the urban fabric of Al-Najada area in order to enhance the social capital and achieve sustainable development targets. Also, another objective is to examine the factors that contribute to socially sustainable development in the regeneration of Al-Najada as a traditional asset in the heart of Doha. A theory by William Whyte on Place-making is an overarching approach for improving a neighborhood, city, or region. It has inspired people to collectively reinvent public spaces as the heart of every community (Lynch and Rodwin, 1958). Strengthening the connection between people and the places they share, the theory of Place-making refers to a collaborative process by which we can shape our public realm in order to maximize shared value. More than just promoting better urban design, it facilitates creative patterns of use, paying particular attention to the physical, cultural, and social identities that define a place and support its ongoing evolution. This approach will guide the theoretical part of this paper since it is believed to result in the achievement of the research objectives: the creation of quality public spaces that contribute to people’s health, happiness, and well-being. Standing from this point, some variables are defined influencing the objective of the research and supporting its main question. These research variables are: streets profile, and open public spaces that are subject to investigation in the upcoming sections of the paper.

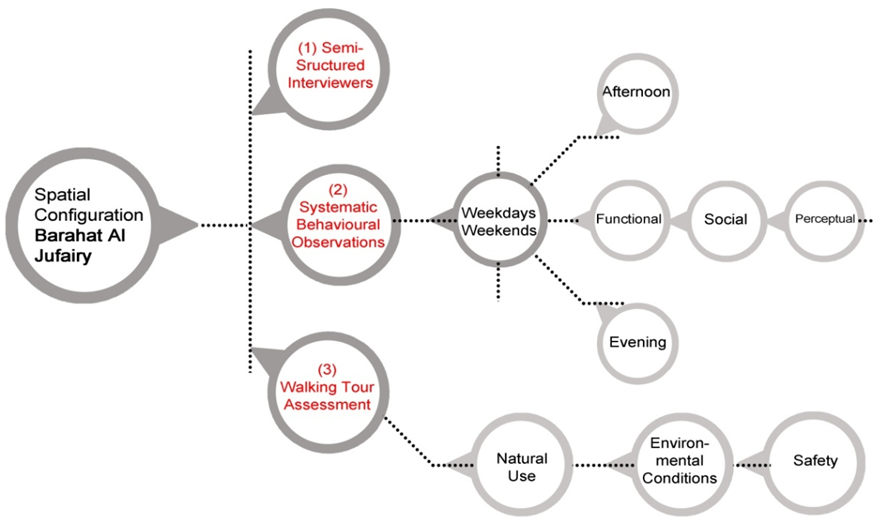

4. Methodology

- As understood from the reviewed literature, environment-behavior studies depend on experimental investigations (Andrea and Dixon, 2011). Sustainable urban development that constitutes a major part of environment - behavior studies is tested and measured through site observations, semi-structured interviews, and walking tour assessments. Also, illustrative sketches are used as common and intuitive method for communicating spatial information and knowledge (Girardet, 2004). In this study, observations and walking tour assessments are the main methods to collect data. Also, morphological analysis of Al-Najada area is considered to understand its spatial configuration and the physical elements that define it. Collectively, these methods help in gathering relevant personal, behavioral, cognitive, and spatial data to achieve the research objectives (Lynch, 1960). The main technique of data presentation and analysis is illustrative images of a 3D massing model developed for Al-Najada area. The following paragraphs describe the research methods in details.

| Figure 9. Spatial Configuration of Al Najada Area, Barahat Al Jufairy |

4.1. Walking Tour Assessment

- This is the starting point of analyzing Al-Najada area. The main aim is to conduct a self-guide tour that begins from the surrounding context, the major points of access, to the urban space. The walking tour assessment facilitates a deeper understanding among the research group of what is meant by an urban space in Doha (Dillard, Dujon, and King, 2009). It is structured in a form that highlights three major aspects: functional, social, and perceptual. This exercise is considered necessary in forming the preliminary impression of the profile of Al-Najada area to indicate its spatial quality. This expands the overall understanding of the everyday life issues that are marginally thought of. Also, this method helps in selecting a specific social profile in a public area for study and analysis in Al-Najada Neighborhood. The following aspects consider the existing conditions of Al-Najada neighborhood: - Natural use: Looking at who goes to the area (the selected study area at al-Najada), in terms of types and mixed users (Heath and Tim, 2012). - Environmental conditions: Witnessing how the surrounding environment enables people to act

naturally in Al-Najada, through displaying their behaviors of comfort and relaxation, and also studying how the people demonstrate personalization and territoriality over the different public spaces in the studied neighborhood. - Safety: Noticing if the study area is safe for the users who are using it and to the users who are visiting it.

This includes considering the social uses of the space; what people do together, how, when, and why (Manzi, 2010). A consensus among the research group concluded the selection of the most popular part of Al-Najada area: Barahat Al-Jufairy. It is a traditional park or open public spaces in the neighborhood. This urban setting is selected based on the dense percentage of people gathering in this particular area. The park is located on the corner of Al-Corniche Junction, which provides a plenty of continuous behavioral actions by people visiting the area as shown in Figure 11.

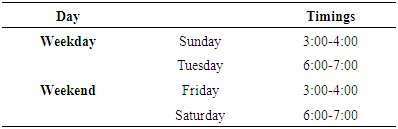

4.2. Behavioral Mapping

- As one of this research methodological approach is Behavioral mapping and systematic behavioral observations in which were conducted of the park or Barahet Al-Jufairy to examine the following aspects: functional, social, and perceptual. According to Worthing, Derek, and Bond systematic observation has followed specific timings in both weekend and weekday to obtain consistent results to serve the purpose of the research (2008).

|

| Figure 10. Location of Barahat Al-Jufairy (The study area highlighted in yellow), source: Google Maps |

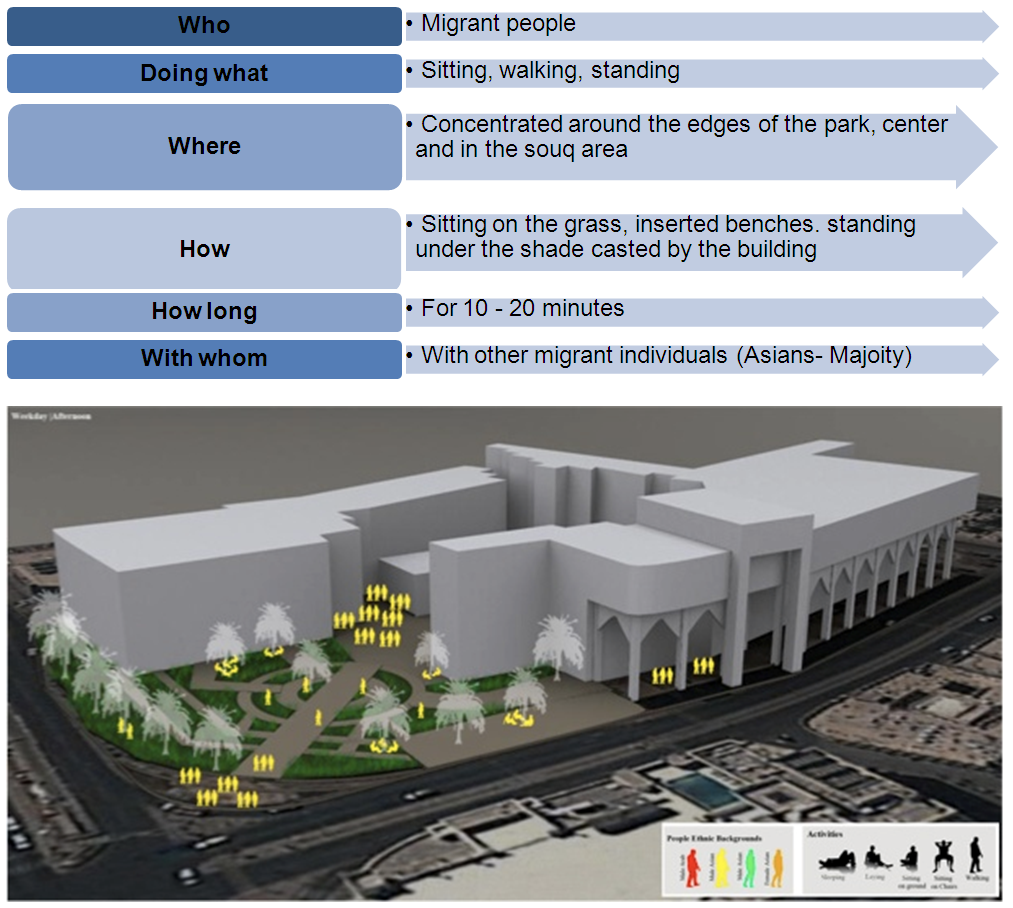

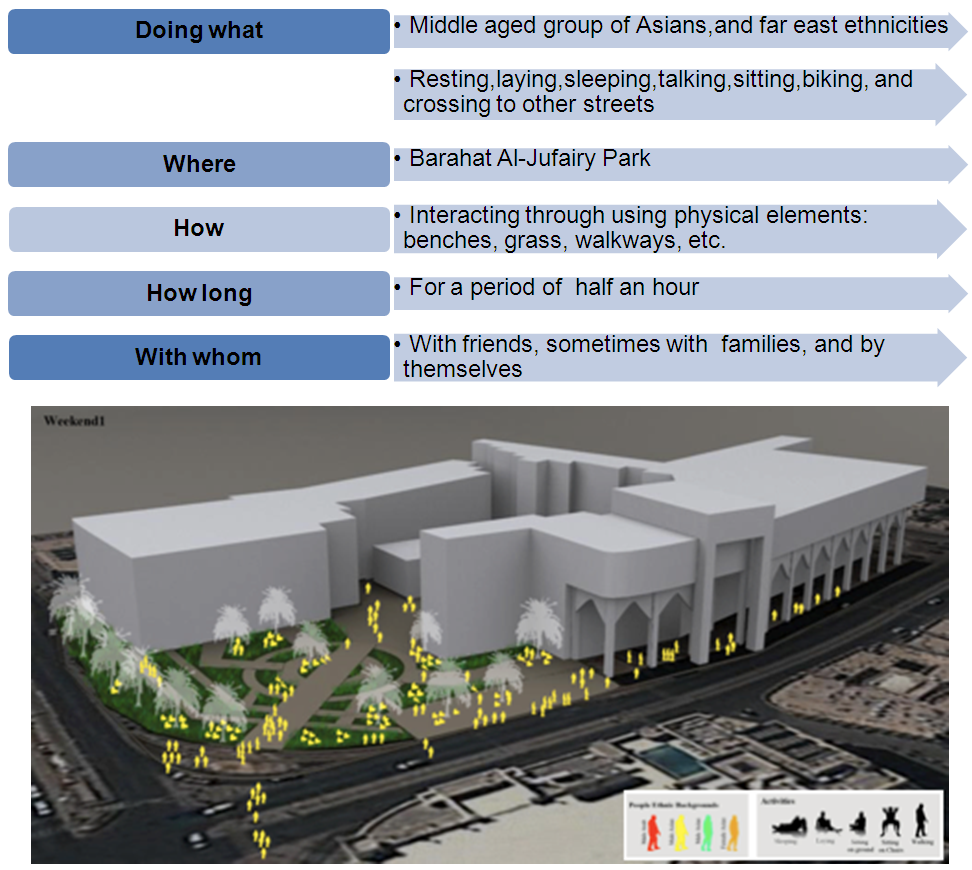

| Figure 11. Observations of Weekday - Afternoon (3:00 - 4:00pm), source: computer generated |

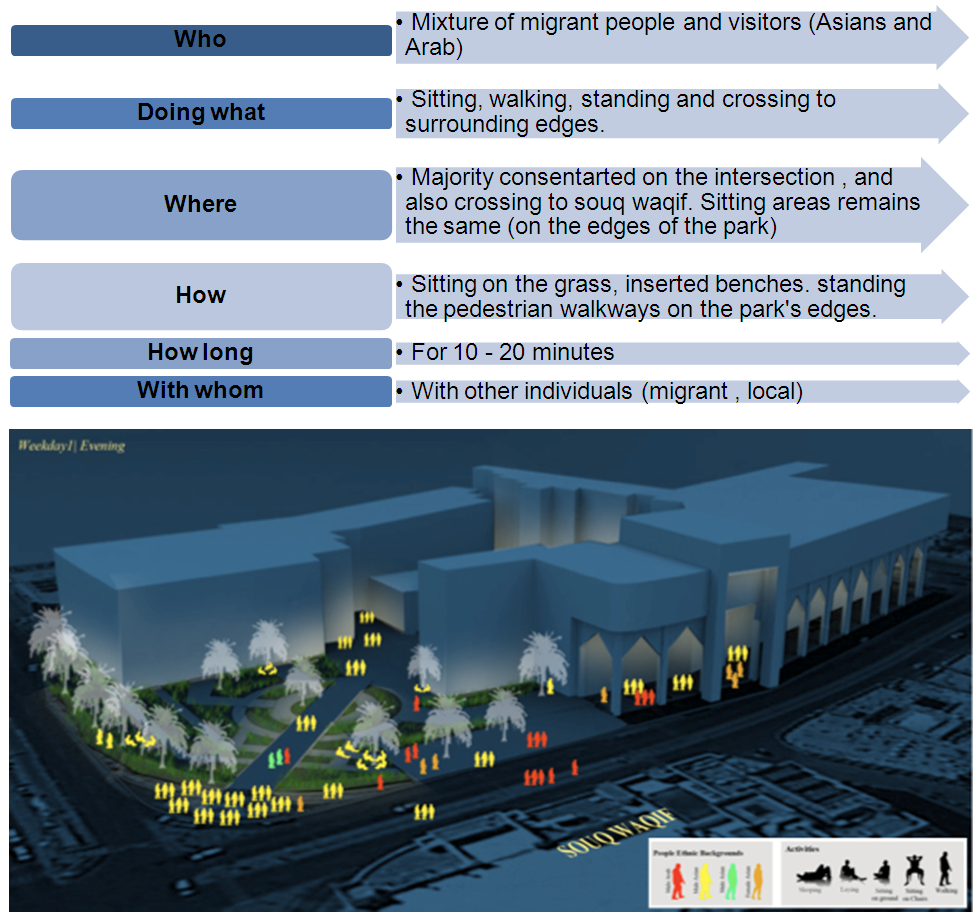

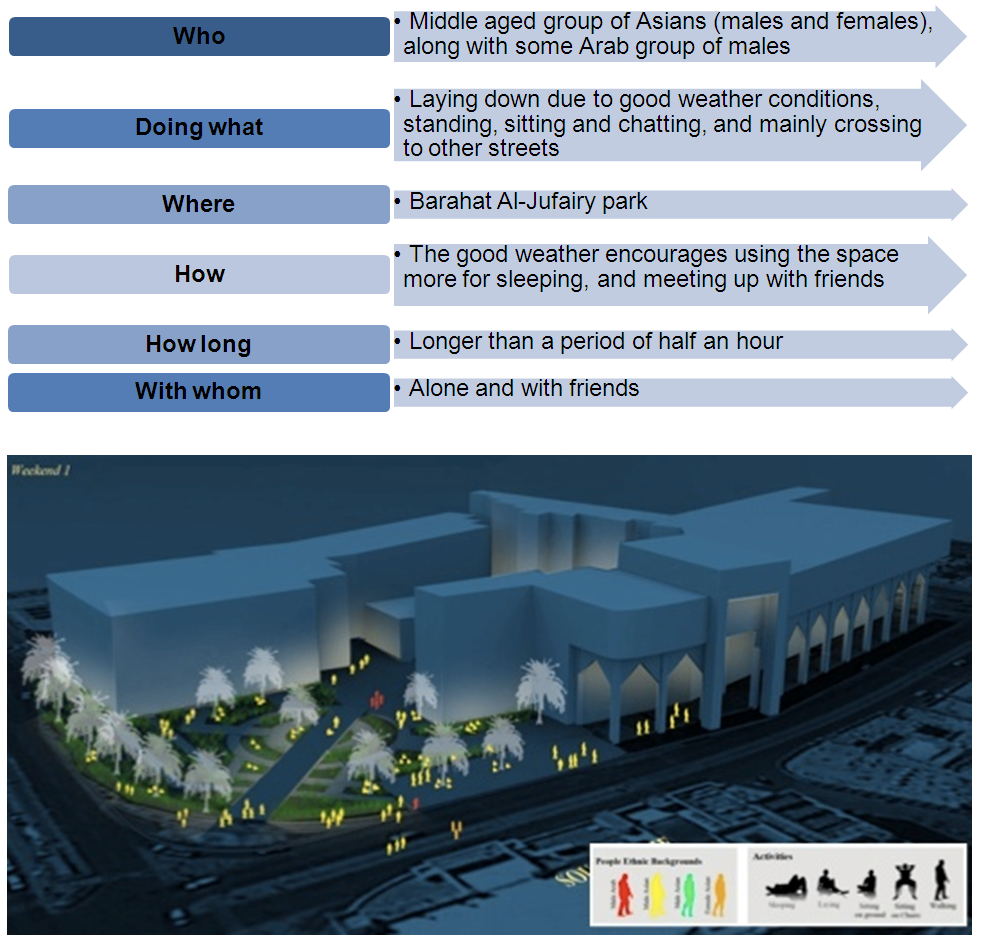

| Figure 12. Observations for Weekday - Evening (6:00 - 7:00pm), source: computer generated |

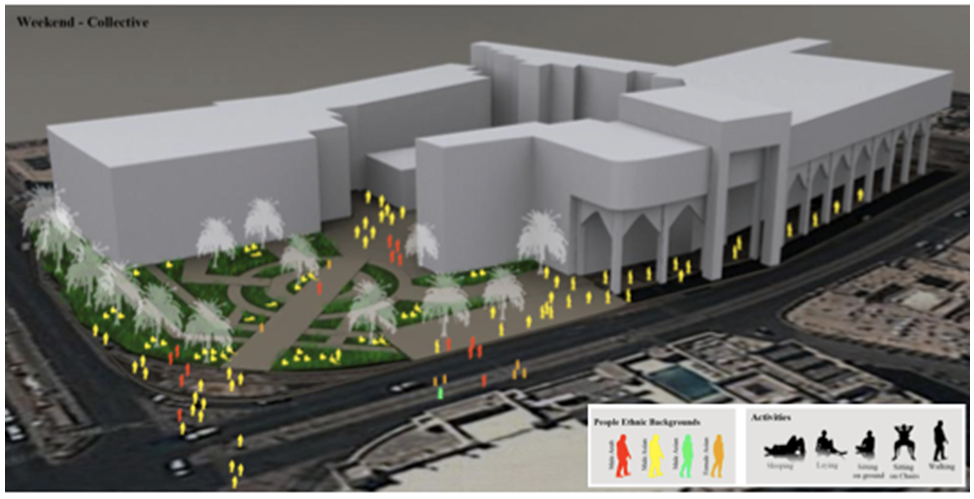

| Figure 13. Observations for Weekend - Afternoon (3:00 - 4:00pm), source: computer generated |

| Figure 14. Observations for Weekend - Evening (6:00 - 7:00pm), source: computer generated |

5. Data Analysis and Findings

5.1. Analysis of the Weekday Observations

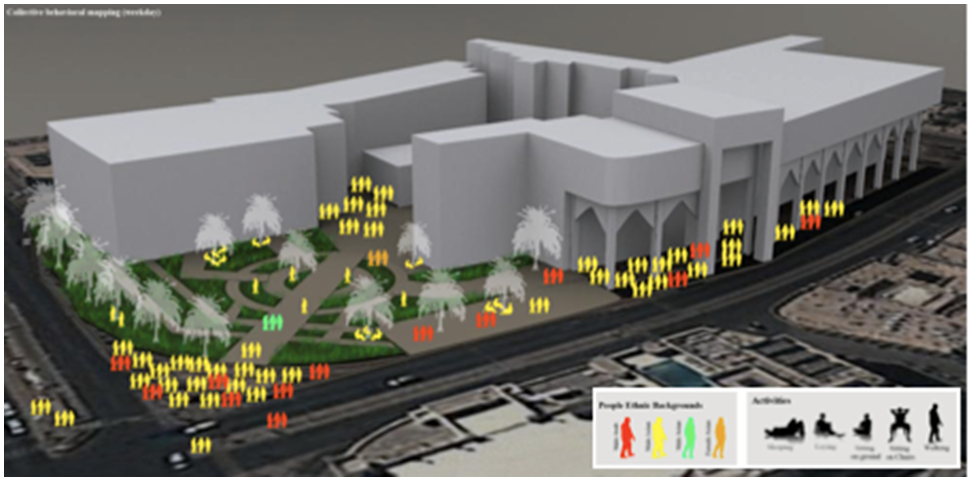

- The park has a strategic location in Al-Najada neighborhood. It is characterized by offering users a pleasant view to observe, overlooking Souq Waqif and also catches the natural flow of the prevailing wind that accommodates users and affords them to relax and enjoy. It is observed that in this specific timing of the day, people form activities corresponding to the surrounding environment (Haskell, 2993). For instance, people are observed walking inside the central circle of the park, passing through the edge of the park to cross reaching the road intersection and Al-Fardan tower. Moreover, people are observed in this space socializing and sitting in groups, targeting shade trees to adapt their sitting to the hot climate of Qatar.At the same day timed in evening, it is noticed that there are a variety of people ethnic backgrounds, in which the majority of them use the park as a passage to the other side of the street, whether towards Al-Fardan tower and Grand Hamad street, or crossing over to reach Souq Waqif. Noticeably, Arab (Qatari) women were part of the observation session, in which they were noticed crossing the park from the arcades of Al-Najada, reaching the central circle to arrive at the street of Grand Hamad.As illustrated in Figure 12 below, people flow in weekdays in both timings of afternoon and evening. Noticeably, the concentration of people flow is located in the intersection of the main road reaching the Souq area and Al-Fardan tower, and the other main concentration will be walking through the arcades of Souq Al-Najada.

| Figure 15. Collective Image of the Weekday Observations, source: computer generated |

| Figure 16. Collective Image of the Weekend Observations, source: computer generated |

5.2. Analysis of the Weekend Observations

- People use the urban setting (Barahat Al-Jufairy) feature a mixed diversity between Asians and Arabs, both males and females (MDPS, 2014). However, the majority of the people dominating the space are male Asians around their middle ages. The setting itself is very dynamic in the weekends, mainly because it is a break for everyone. In terms of functionality, the space is efficient in which different functions are performed; this includes sleeping, lying down, and sitting on benches and on grass, walking, crossing, and biking. In general, people go to Barahat Al-Jufairy) to sit, relax, and lay down under the shade trees and on the watery grass. Intuitively, the park (Barahat Al-Jufairy) allows people to act normally. As an urban environment, it does not limit their uses nor their choices. For example sleeping under the shade of the tree during afternoons, or sitting and laying down on the edges of the street or on the ground, sitting on benches, continuous and heavy walking under the shaded arcades, and finally meeting up with friends around the trees. People in the afternoon tend to gather up with friends for a long time, and sometimes sleep for a period of half an hour, and in the evening they tend to sit and talk. All in all, and according to the site observations, the park is used by different users of different backgrounds, and features a good example of functional and social aspects of urban environment. However, it lacks supporting facilities that respond to efficient planning of the public space as a venue for social interactions. The walking tour assessment along with the systemic observations and behavioral mapping conducted on the park or (Barahat Al-Jufairy) concludes the following in terms of the functional, social, and perceptual aspects: ● Functional aspects In terms of functional aspects, the park provides diverse activities such as laying, relaxing, sitting, sleeping, walking, crossing to other streets, biking, and interacting with other people. To some extent, the park is environmentally responsive because of the existence of natural and man-made elements that accumulates different activities as a result of the sense of affordance of the occupants using these spaces. The form of the space is mainly appropriate for the users because it is clear, visible, and leads a direct path from and to variant destinations (Kelbaugh, 1997). Users respond to the studied environment comfortably, as a result they demonstrate their personal reliefs through aspects such territorially, personal space, and adaptability. ● Social aspectsAs mentioned in the functional aspects, the park is a social node for most of the migrant communities that work and live in the surrounding area of Al-Najada. These people create the social nodes around different areas within the neighborhood, especially the park itself (Alshuwaikhat, 1999). Despite the fact that there aren’t that much of cultural diversities in the street due to the majority of male Asians in their middle ages from the same ethnic backgrounds frequently use these spaces, however from time to time there are few female visitors that come to the street for a specific target, such as going to a specific shop. All in all, as observed the park is inclusive and is not inviting to the outsiders. ● Perceptual aspects As a result of the systematic visits to the site, it was perceived that users in the space exhibit a high level of comfort through territoriality, and personal space, in where it is obvious that the proximity level between groups are relatively high. The park is memorable in terms of the existing structures such as the designed landscape and seating benches. Finally, this park affords its users a sense of belonging, and is viewed heavily during weekend gatherings, in where people will meet up as a group for relaxation and leisure opportunities (Mehrabian and Russel, 1974).

6. Discussion and Conclusions

- This research study, conducted on designing for social interactions in neighborhoods, reveals that the sustainable development of neighborhoods is linked to the quality of public open spaces. As shown in the findings of this research study, people behave in different ways depending on their cultural backgrounds, beliefs, and origins. The environment affects them, and as a result, this makes people look like they belong to one background, practicing similar functions (Gehl, Jan, and Gemzøe, 1996). The neighborhood of Al-Najada is inclusive and is not inviting outsiders since it mainly focuses on one major group of people: migrant communities. These communities affect the Qatari identity because they are located in the old center of Doha, and as a future resolution this place should be rehabilitated. The planning vision for Al-Najada area is to revitalize it, making it one of Qatar’s significant meeting points, promote Qatar’s cultural identity in the eyes of the tourists, and assign the existing spaces with new functions, in a sense that it will not affect the context of the traditional theme (Khairy, 1993). Al-Najada area will be a continuity of Souq Waqif; however the experience will be different; and by continuity we refer to connection. It will provide a new experience for the resident workers as well for the visitors; and potential residents from different backgrounds.In the past, Al-Najada used to be a beautiful urban space since it used to contain all needs of its residents and visitors. It constituted of Souq area, plaza, park, and residential areas. These urban components of Al-Najada used to complete the neighborhood as being a mixed-use neighborhood in Qatar that serves the need of its people. The main significant feature of Al-Najada is envisioned to be a complete urban place in Doha, utilizing the existing features of the area. Collaboration is deemed necessary in achieving this goal. Planning team consisting of architects, urban planners and designers, engineers, historians, anthropologists, social specialists, and activists should be comprehensive enough to achieve an inter-disciplinary approach towards implementing social interaction and livability in Al-Najada neighborhood. The existence of several landmarks, and the introduction of new functions will attract the locals and non-locals once again to come and explore this development of this valuable place (Gehl, 1987). This research study focused on Barahet Al-Jufairy Public Park as a case study that examines the different societal dimensions of different users in Al-Najada neighborhood. The results have varied depending on the specific timings assigned for the systematic behavioral observations and this have affected the type of activities and the profile of users, which was clearly noticed in weekdays and weekends.

7. Recommendations

- A set of recommendations based on planning and design guidelines are to be developed to encourage social interactions in the area and, thus, make it livable (Black, 1990). Al-Najada area should be re-planned according to the following suggested guidelines in order to implement social sustainability:1. Al-Najada area should have a variety of functional attributes that contribute to a resident's day-to-day living (such as residential, commercial, or mixed-uses).2. Al-Najada should accommodate multi-modal transportation (such as pedestrians, bicyclists, vehicles, metro, etc.).3. Al-Najada should have design and architectural features that are visually interesting.4. The Qatari history and heritage adaptation is recommended in future design guidelines.5. It should encourage human contact and social activities.6. It should promote community involvement and maintains a secure environment. 7. It should promote sustainability and responds to climatic demands.8. It should have a memorable character.9. The accessibility and smooth transition from one neighborhood to another should be enhanced.10. Special attention to the neighborhood-targeted residents must be considered.11. Municipal attention and follow up is a must for producing and implementing a set of proposed design guidelines and legislations that to be implemented in the regeneration of Al-Najada and other such like neighborhoods.It is also recommended that the municipality take immediate action for revitalizing the area in order to protect its authentic qualities through introducing social activities.

Future Research Opportunities

- This research study can contribute in the planning process future developments. People should be an essential component of the planning process in which considering their social health is deemed necessary. It is noticed that the background and origin of the people are demonstrated through personal space, and levels of territoriality (Abu-Ghazzeh, 1997). All in one, this research study reveals significant facts about how people interact with their urban environment, and how the urban environment affects and supports their behavioral performances. Further research studies can be conducted to investigate the relationship between the personal preferences of users and urban resilience.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to acknowledge the support of Qatar University for creating an environment that encourages scientific research. This study was developed as an assignment at the course "Urban Design in Practice" for the Master in Urban Planning and Design Program at Qatar University. Also, we would like to acknowledge the effort of the people working at MMUP for their collaboration - for handling relevant visual data and cardinal documents for the purpose of this research study (MMUP, 2015). Finally, the authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which contributed to an improvement of this paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML