-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2015; 5(2): 30-44

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20150502.02

Characteristics of House Ownership and Tenancy Status in Informal Settlements in the City of Kitwe in Zambia

Thomas Kweku Taylor1, Chikondi Banda-Thole1, Samuel Mwanangombe2

1Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Built Environment, Copperbelt University

2Samuel Mwangombe is a 2009 Final Year student in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning in the School of Built Environment

Correspondence to: Chikondi Banda-Thole, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, School of Built Environment, Copperbelt University.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The evolution and development of informal settlements is hypothesized to be associated with the denial of the urban poor and the low income individual’s access to urban residential land for housing development. Though this assertion is strongly defended by most urban planners and local government decision makers, the emerging hypothesis, which seems to have some validity, is the significant role played by small scale landlords in the supply of housing in the informal housing market to generate rentals from the low income. It is purported in the literature that, the rapid growth of informal settlements within some major cities in the developing world is as a result of small scale landlords who build houses in informal settlements to be rented out to the needy. This is an intriguing assertion that requires some empirical investigation.The paper is an attempt to validate the assertion with respect to the mushrooming and growth of informal settlements in the City of Kitwe in Zambia which is encircled with approximately thirty informal settlements. The evidence from the research proved that, a large segment of the urban residents lives in rental accommodation in squatter settlements. The supply of informal rental housing built without following planning procedures or local authority by-laws is growing much faster than formal housing. Furthermore, house-building in informal settlements by entrepreneurial landlords or informal residents takes place without regard to planning rules or construction standards.

Keywords: Small Scale landlords, Housing Market, Informal Settlement, Tenants, Kitwe

Cite this paper: Thomas Kweku Taylor, Chikondi Banda-Thole, Samuel Mwanangombe, Characteristics of House Ownership and Tenancy Status in Informal Settlements in the City of Kitwe in Zambia, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2015, pp. 30-44. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20150502.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The immense growth of informal settlements in developing countries is alarming. The increasing number of people living in less-than-desirable conditions attests to the absence of effective solutions and the need for adequate and affordable shelter. According to UN-HABITAT [1] (2003), nearly one billion people are slum or informal dwellers [2] [3]. This number is likely to grow to an estimated 1.43 billion by 2020 or double to about 2 billion by 2030. This unprecedented urban growth in the face of increasing poverty and social inequality, and the projected increase in the number of people living in slums mean that the United Nations Millennium Development goal (MDG) 7 Target 11 to improve the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers by 2020 should be considered the absolute bare minimum that the international community should aim for.Faced with this challenge, man’s living environment has become a subject of serious scrutiny and concern for its users in today’s contemporary world [4]. Zambia is one of the most urbanized countries in Sub-Sahara Africa with about 47 percent of its population living in urban areas and 70 percent of these reside in informal slum settlements [5] [6]. The percentage of urban population by province ranges between 78 and 82 percent for Copperbelt and Lusaka Provinces respectively, to 9 percent for Eastern Province [7]. Of the 47 percent, approximately half live in the cities on the Copperbelt. The population growth rate for slums in Zambian urban settlements as recorded by UN-HABITAT in 2001 is 3 percent annually. Informal settlements are a common feature of all municipalities in Zambia. Their growth is characterized by the brisk transactions in the informal housing market. Unlike the formal housing market, the suppliers of the informal housing market are perceived as exploiters of the low income in the society. For years, the debate on housing in developing countries focused on the idea of informal settlements as a vehicle of ownership for the poor through self-help processes. For instance, research on informal rental transactions in South Africa indicated that the primary source of supply of this form of accommodation is small scale subsistence landlords who are often older and poorer than their tenants and are women [9]. Nevertheless, the assumption of many self-help theorists is that, everybody in a squatter settlement is an owner (or potential owner) was never true. Evidence from different countries such as Kenya [10], Tanzania [11], South Africa [12] and Brazil [13], proves that a large segment of the urban poor lives in rental accommodation in squatter settlements and informal sub-divisions. In a similar vain, the Social Housing Foundation [14] reiterated that informal rental is a vitally important and growing part of the housing market for the poor in South Africa [15] [16]. In a context of deteriorating economic conditions, and with the land scarcity pushing the poor to the outskirts, invasions are less frequent. For some families, ownership even in its cheapest form has become increasingly inaccessible. As ownership becomes less feasible, rental and shared housing become more frequent options among poor households [17]. In the South African case, the concept of the backyard squatting has become the order of the day whereby in some instances the tenants often provide their own structures on the space rented from the landlord and therefore may also be suppliers of accommodation [18] Backyard dwellings are informal shacks, typically erected by their occupiers in the yards of other properties and are uniquely South African [19]. The City of Cape Town housing estimated in 2006 that 75,400 households live in backyard dwellings [20]. Letting yard space is perceived by some housing experts as the direct response to the failures of housing policies to recognize poor people’s poverty as well as their uses and understandings of land and property [21]. Surveys in some unplanned settlements have revealed that small scale landlords develop rental housing units and improve existing houses leading to expansion of informal settlements in urban areas basically as form livelihood strategies [22].

|

2. The Problem

- The City of Kitwe and other urban areas on the Copperbelt Province of Zambia are experiencing the development of new informal settlements and expansion of existing ones. As long as informal settlements continue to evolve, develop and expand unsustainably, the settlements will continue to occupy and encroach on contested spaces in the cities and thus continue to be a source of environmental, social and moral problems. Urban populations in Zambia have increased explosively in the past 50 years, and continue to do so as the number of people born in cities increase and as people continue to migrate from rural areas to urban areas. The rate of creation of formal sector urban employment is well below the expected growth rate of the urban labour force, thus, in all probability, the majority of the city and urban entrants (i.e., as residents) are most likely to be informal settlement residents. The observed trend in other parts of the world especially in Kibera (Kenya) and Soweto (South Africa) is that the expansion of slum housing is as a result of small scale housing entrepreneurs from high and middle income classes who build homes to generate capital. The speculation is that, the housing development and delivery system in other parts of the developing world might prevail in Zambia, i.e., the middle and high income individuals who are comparatively higher on the social ladder of development might be the main drivers of the housing market in the informal settlements. The other school of thought is that, even low-income individuals living in informal settlements and low-income formal townships like Buchi, Kamitondo, Chimwemwe (located in Kitwe) and others might be land and housing development speculators.With about 60% of the Zambian urban population being in the low-income bracket who cannot afford the high formal housing prices, this has created an increased demand for informal housing which in return has motivated housing developers from other income groups to infiltrate into the informal rental sub-market by constructing affordable housing using cheaper building materials for rent to the urban poor. Based on the factors highlighted above the following questions evolved:a) What is the housing ownership tenure pattern in informal settlements in Kitwe?b) What is the nature of the rental sub-market in informal settlements of Kitwe?c) What are the factors influencing the demand and supply of rental housing in informal settlements in Kitwe?d) What are the legislative instruments that support or constrain the functioning of the informal housing development and rental housing?e) What are the effects of informal housing development and rental housing on the spatial urban development in Kitwe?

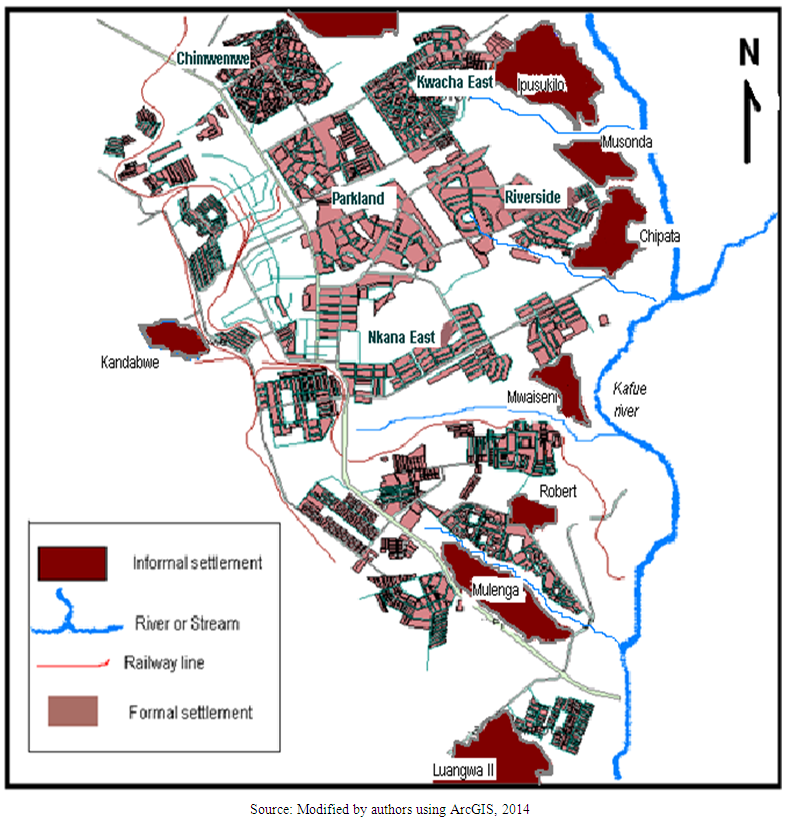

3. The Study Area Profile

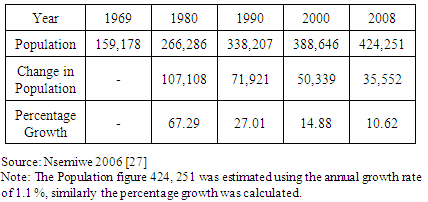

- The study areas are settlements located in the City of Kitwe. Kitwe is in the central part of the Copperbelt Province and lies on a gentle sloping plain at a mean attitude of about 1295 metres above sea level between 12° and 13° East, and longitudes 27° and 29° South. The city covers an area of 777 square kilometres and links major districts and urban areas such as Mufulira, Chingola, Luanshya, Ndola and Kalulushi [25]. The history of Kitwe is traced to the beginning of mining on the Copperbelt region. Kitwe is the third largest city in Zambia and was founded in 1936. It achieved Municipal status in 1954 and City status in 1967. In the last twenty years, Kitwe experienced rapid environmental deterioration and a plethora of development related problems. The city has 23.8% of the Copperbelt Province population with a labour force participation rate of about 48-58% and unemployed population of about 32.6% (CSO, 2000) [26]. Based on the Census Statistical Office (CSO) 2000 report, the population for Kitwe stands at 388,646 with an estimated 1.1% annual growth rate. In terms of population density, the city is 484 persons per square kilometre and it has an overall dependency ratio of 80.3% with child and aged dependency ratios at 77.95% and 2.5% respectively. In terms of economic structure and activities, the city is the most industrialized on the Copperbelt, with the core economic activity being mining and mining oriented activities. Commerce and trade is on the increase due to the revitalization and resuscitation of the copper mines. This is evidenced by the increase of both formal and informal commercial activities.The city of Kitwe like the other cities in Zambia is expanding physically as a result of the uncontrolled evolution, growth and expansion of informal settlements. The history of informal settlements in Kitwe can be traced back to the discovery of workable copper ore on the Copperbelt around the 1920s that made the territory an economic centre of gravity and accentuated the disparity between rural and urban economic opportunities for Africans. With the establishment of mining activities in Kitwe, it became obvious that there was need for employment. However, potential labourers were constrained on their mobility from the rural areas to urban areas. The colonialists only provided housing to workers while immigrants that were unemployed built their own houses. This led to the creation of squatter settlements for charcoal vendors in the mid fifties. The local authority turned a blind eye to their presence because they located outside colonial local authority boundaries. Some of the settlements are Mufuchani and Kamatipa which are presently within the city boundary. The removal of travel restrictions that were imposed by the colonial administration after independence led to an increased rural-urban drift of people in search of employment opportunities and perceived good life. This situation ultimately led to increasing urban housing demand that has never been satisfied up to-date. This has led to continued proliferation and expansion of informal settlements in Kitwe with 90% of the settlements being on the northern and eastern non-mining areas of the city along the western banks of the Kafue River.

|

|

| Figure 1. Map Showing some of the Informal Settlements in Kitwe |

4. Literature Review

- In the last ten years, studies on rental housing have experienced a remarkable expansion. The following discussion covers issues such as informal housing and accommodation, rental housing policies and their failures, the variety of rental forms in informal environments, their role as income generators, the nature of the demand and supply including the unique phenomenon of backyard squatting, and the landlord-tenant relationship. Tenants of informal rental housing tend to be young and are usually at the bottom third income bracket of population. Gilbert [33] (1983) identified two stereotypes of the demand for informal rentals. The first is based on Turner's 'bridge header' model (1968): the 'upwardly mobile migrant who chooses to rent until obtaining a secure job and then moves with his family to ownership in a spontaneous settlement.' The second stereotype is the 'stagnating tenant' suggested by Van der Linden [34] (1994): the poor family unable to own because of the unavailability of land and "which rents only as an unsatisfactory alternative." Informal rental housing has certain inherent advantages from the individual’s point of view, such as low initial investment and greater flexibility for future tenure options. This makes it a preferred alternative for more mobile younger households, the floating population and new migrants to seek aid on the informal housing market.

4.1. The Suppliers of Informal Housing

- Landlordism in squatter settlements seems to vary between two extremes: the small scale landlord renting one or two spare rooms, and the 'professional' landlord that speculates with the demand of cheap housing [35]. Several studies report widespread petty landlordism, but no evidence of speculative practice (Watson, 2009, Lemanski, 2009, Gilbert, 2008, South African Social Housing Foundation., 2008, Bank, 2007) [36]. The list is endless. Gilbert (2008) [37], hinted that, landlords are much less influential than they were before in the sense that the rich and powerful are more likely to invest in shares, land or commercial; properties leaving the ownership of rental housing to a myriad of small landlords.Others have found a completely reverse situation. Practically, the whole squatter sector in Nairobi constitutes a rental sub-market exploited by elite [38]. In Ghana, the practice has been the construction of traditional compound houses which were conducive for renting for beginners of life. However, there is shift in paradigm whereby the potential landlords are more inclined to purchase from real estate agents. Turner (1987) [39] in Poona, India, and in Thika, Kenya, described a similar form of landlord operation based on illegal slum development for rent. Gilbert and Varley [40] (1991), in Guadalajara and Puebla, Mexico, reported a mixture of both types with slight predominance of small scale landlords.Rentals as Source of Income Room letting often contributes to supplement incomes of poor households. Some landlords can even improve their housing status from the low cost rentals derived from these informal subdivisions. In Bangkok, slum dwellers have improved their status in this manner [41]. In Karachi, there is also a similar phenomenon: room letting in informal subdivisions has helped dwellers to finance the improvement and enlargement of their houses. Indeed, informal rentals seem to play a financial role for some low-income home-owners. Most evidence from Latin America suggests that, rentals are a way to generate extra income rather than a way to make profits. In Bucaramanga, Colombia, approximately 90 percent of landlords rent to supplement low incomes. Similar findings, but in lesser degree, have been reported on Mexico, Chile, and Venezuela [42].In Jakarta, research by Marcussen (1990) [43] showed an increasing trend in number and variety of rental options in peripheral ‘kampungs’. As in Karachi, room letting plays a supporting role for most households and frequently it contributes to finance house extensions. Quite often, the rental forms develop in small-entrepreneurship combining room letting, shops, small home-based industries and sub-division and sale of plots. Although it is clear commercial bias, the system may be characterized as subsistence rent farming, and is in this sense an aspect of the household economy [44] (ibid). Landlords or home-owners rent for a range of reasons. Renting serves as a safety net against precarious employment, meeting household expenditure, housing improvements, a regular source of income when moving from waged employment to own account forms of employment, capital investment and rotation in business, as a form of pension after retirement and old age and as investment for the next generation.Demand for housing can either be based on need or as a choice of tenure. The choice in the formal market is usually posed between owning or renting a house [45]. In informal sub-markets the options include home ownership through squatter or illegal subdivisions, or rentals such as a bed, a room, a house or a piece of land [46]. Studies have also shown that, there is no direct correlation between tenure choice and social class or income groups because households with the same level of income choose different forms of tenure and vice versa [47]. Although choices can only be made within the constraints which determine what is available, where and at what price, even the most disadvantaged section of the population usually has more than one alternative to choose from". Van Lindert (1991) [48], analyzing housing shelter strategies in low income groups in Bamako (Mali) and La Paz (Bolivia) argued that, both the "choice" and "constraint" arguments can apply to different social categories within the same income bracket.According to Cocatto (1996) [49] and Wadhva (1988, 1989), [50] location and affordability are the strongest factors influencing housing preferences. Mehta and Mehta (1989) [51], related housing preferences to households’ stage in life cycle, and distinguish a set of three determinants or regions, i.e., socio-demographic and economic characteristics, the level of affordability, and the perception of housing opportunities and prices. At an early stage in life cycle, households base their preferences on their housing background and their primary housing needs. In the second phase, their preference is influenced mostly by the perception of affordability and the awareness of housing opportunities in the market. Finally, the third stage comprises a process of housing adjustment driven by changes in aspirations and mismatches between housing type and need. This suggests the use of models where age is interacted with the main determinants of tenure choice to adjust for the different stages in life cycle. Daniere (1992) [52] indicated that, family size, education, income and mobility are powerful forces explaining tenure choice in Cairo and Manila.Grootaert and Dubois [53] (1988) used maximum likelihood probity to analyze tenure choice between owing or renting in informal settlements of Ivory Coast cities, concluding that stage in the life-cycle and mobility are the two prime determinants of tenancy status. Similarly, based on a logic model for Ibadan, Nigeria, it was concluded that, income investment motivation for ownership, number of children, house head gender, life cycle-variables, duration of stay in the city and access to land on the basis of ethnic qualification is the main determinants of housing tenure [54]. Huang and Clark in China, using a multilevel modelling technique, demonstrated that, tenure choice in Chinese slums is affected by socioeconomic characteristics, formal housing market mechanisms and institutional factors, with the relationship among the state, work units and households still playing important roles in tenure decisions [55].Jacobs and Savedoff (1999) [56] used data from two cities in Panama to evaluate the determinants of tenure choice in the context of two models. In the first model, households choose between owing or renting, while the second model classifies households as buyers (finish housing), renters or builders (progressive housing). Their results showed that, life cycle variables influence the decision between owning and renting, whereas choosing between buying a complete housing unit or progressive building it, depends on income and assets levels. Similar conclusions were reached by Koizumi and McCann (2006) [57], who did an empirical study on housing tenure in Panama. They concluded that the extended models perform better in identifying which household characteristics are associated with a particular tenure option. Their results suggested that, the age of household head and the numbers of economic dependants are the key factors to explain choice between renting or buying a dwelling. On the other hand, education and income levels explain whether the household purchases a plot to build or a complete dwelling unit.In Tanzania, a report by University College of Lands and Architectural Studies (UCLAS) and ILO [58], indicated that, in Hananasif unplanned settlement, in Dar-es-Salaam, there were approximately 20,000 residents (5,045 households) in 1,777 residential housing units. They further indicated that there is a strong rental housing sector though there is low degree of absentee landlordism (i.e., 70% of the households as tenants and 30% house owners. Nguluma (2003) [59] also disclosed that the house owners in Hana Nasif supplement their regular income through renting out rooms while others depend entirely on their income from rent. His study revealed intriguing statistics, i.e., 17% of landlords interviewed own 2 or 3 houses in the settlement which they rent out. Majority of landlords (72%) have increased the number of units they rent out; 60% had created between 1 and 3 additional units since upgrading started, 12% have even increased their stock by 4 to 6 units. Twenty-two percent (22%) of landlords in 2005 rent out the same number of residential rooms they already let before upgrading 7. In total, the housing stock has grown by 84% between 1994 and 2005.Informal rental housing has been integrated as one of livelihood opportunities, especially as income and employment generation activities (building construction), catalyzing housing densification and crowding (ibid). Similarly, in another study by UN-Habitat (2002), it was noted that much of the squatter land in Kibera has been acquired or allocated by politicians and government employees with enough influence to ensure that they are not displaced. In its sample of 120 landlords, 41 per cent were government officers (the majority of them were Kikuyu), 16 per cent were politicians, and 42 per cent were other absentee owners who visited Kibera occasionally. Only a handful of the structures belonged to people who lived in the slums. This is unlike the situation in Mathare and Pumwani, where a large number of investors are residents who lived at a level fairly similar to their tenants and demonstrated a keen interest in maintaining the community and improving it [60].In Nairobi, 70% of the urban population lives in slums. In the case of Nairobi, 80% of the slum dwellers live in rental shacks which are profitable to their owners. The surprise is that most tenants pay each year an estimated rental amount of US$31 million (Ksh 2.35 billion) [61]. Rents in Nairobi’s slums increase with number of rooms and are higher for units that have permanent walls and floors, as well as those with connections to electricity or piped water. They are higher in neighborhoods that have a public school, and the division in which a unit is located imposes a premium or discount on the rental value.

5. Research Methodology

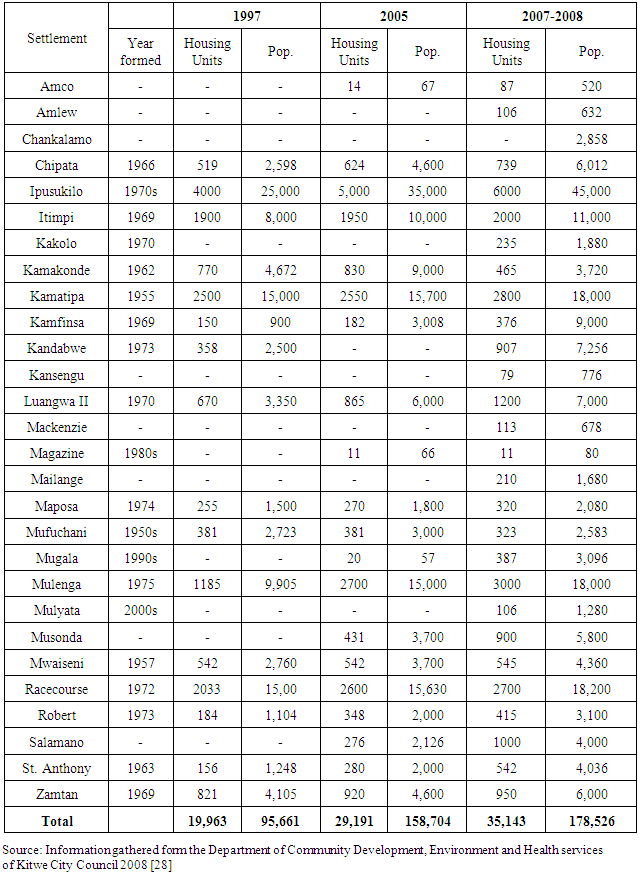

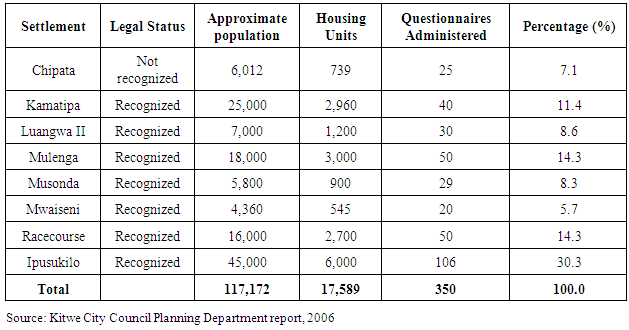

- The research used purposive and stratified cluster sampling methods to ensure that the sample was adequately representative as well as generating maximum variation. Based on twenty-eight (28) informal settlements with a total population of 117,172 residents accommodated in 17,589 housing units, eight (8) largest settlements were selected at random (see Table 4). The housing unit was used as a sampling element. A sample size of 350 households was selected. The questionnaires were administered to the respondents in the eight informal settlements and distributed based on the number of housing units in each settlement as illustrated in Table 4.Based on the descriptive statistics on head of household responses, contingency tables were generated to test for Chi-square and statistical tests of significance between specific variables. The following section presents the analyses of the data generated for the study.

|

6. Data Analyses

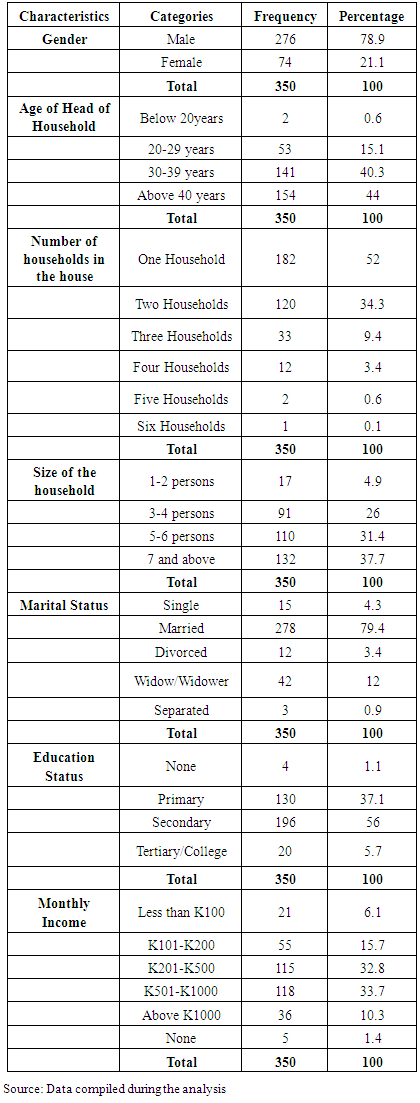

- The analysis focused on assessing the house ownership patterns, nature of the informal rental housing market and its main actors in informal settlements in Kitwe. The analysis aimed at ascertaining the factors that influence the demand and supply of informal rental housing in the settlements. The analysis begins with the descriptive statistics of socio-demographic characteristics of the respondent (see Table 5). It was realized that male headed-households dominated the female-headed households with approximately 80% representation with female-headed households accounting for 18% of the households. However, it should be stated that, most of the interviews were conducted with women because the males were out for work or undertaking income-generating.

|

|

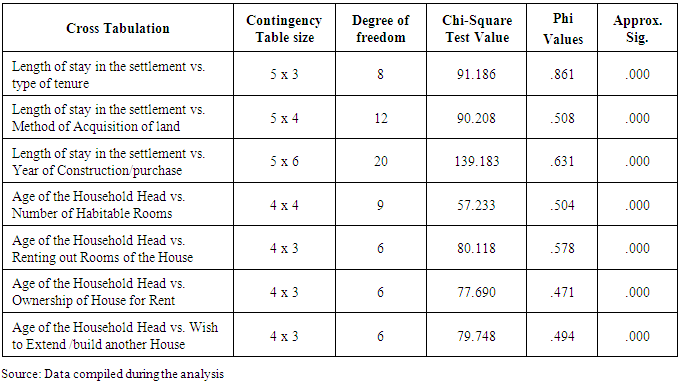

7. Two Variable Analyses Using the Contingency Table

- The variables of length of stay in the settlement and type of tenure were examined through a cross tabulation technique. The variables were analyzed using Chi-Square test and the Pearson Chi-Square value was found to be significant (χ2 = 91.186, df = 8) as shown in Table 7. It was concluded that, there is a relationship between the length of stay and tenure choice. The association is based on the approximate significant value which is less than .05 (i.e., ρ < .05). This is reflected by the increase in percentage of the owner-occupants as the residents’ length of stay in the settlement increases. This is accompanied by the decrease in the percentage of tenants as most of them become owner-occupants.In summary, it can be concluded that, as their length of stay in the settlement increases, tenants decide to become owner-occupants because they become aware of the means to homeownership. The other factors for the change of tenure include expanding households and rentals being expensive on the long-run. Table 7 shows the results of the cross tabulation of type of tenure and the length of stay in the settlement.The cross tabulation analysis was undertaken to ascertain whether there is an association between the ‘wish to extend or build another house’ and the age of the respondent. Table 7 shows the statistical findings of the cross tabulation. The chi-square test value was found to be considerable (χ2 = 79.74, df = 6,) ρ < 0.001. The result represents a positive association between the two variables.

|

8. Factors Leading to Increased Demand of Informal Rental Housing in Kitwe

- The Kitwe City Council is aware of the increase in informal housing in informal settlements. The main factors perceived to have led to increased demand of informal rental housing in Kitwe include:i) Inadequate and unaffordable formal housing leading to high demand of cheap housing. ii) Land alienation and Deed Registry procedures are highly centralized and cumbersome making it difficult for the low-income to access landiii) Rapid population increase and industrial growth in the cityiv) Discrimination of the poor in assessing land for housing development v) Political interference and corruption in the land delivery systemvi) Unemployment and income poverty: source of income for informal house ownersvii) Home owners do not pay to the Council and therefore can lease out more than one house at a time

9. Nature of the Rental Sub-Market in Kitwe’s Informal Settlements

- The findings of the study suggested a range of suppliers of non-ownership alternatives. Some of the landlords are relatively wealthy while others are just as poor as their tenants who live in the same settlement and rely on their rentals for a minimum subsistence. From the supply side, two types of landlords dominate in the informal settlements of Kitwe i.e., the small-scale landlords (informal residents) who rent out at least one spare or extra room of their dwellings or own houses (mostly are old and were formerly occupied houses by the landlords) that are being rented out, and the elite landlords who speculate with the demand of cheap housing. The survey indicated that, approximately 25% of owner-occupants rent out rooms and 13% of the households (mostly retirees and retrenched owner-occupants) owned houses in the same settlements that are being rented out. This category of landlords rent out rooms or houses as a means to secure a basic subsistence or as a form of supplementing and stabilizing their low incomes. The wealthy landlords are involved in the informal rental markets as an investment to make profits. They take advantage of the weaknesses in the land allocation system in informal settlements and avoiding taxes (since property owners in informal settlements in Kitwe do not pay rates) to achieve substantial return in their investments. Demand of non-ownership alternatives in informal settlements of Kitwe is mainly of the tenancy form of renters, who pay a periodical (monthly) sum of money or rent. The study revealed that most of the renters (about 70%) were young couples below the age of 30, single persons and single women (divorcees and widows) with children who are unemployed and are unlikely to afford formal housing. Most of the tenants have small family sizes. The results also revealed that there are renters who are in well-paying employment such as technicians, teachers and other government employees. Most tenants who are in well-paying employment claimed that rental housing in the formal settlements were very high, so they tend to sacrifice location, services and housing quality for affordable accommodation, to spend less on housing and pursue other priorities in life such as educating their children.On the average, renters have been in their accommodation for 2 years and have an average household size of 4 persons. Most of them are occupying averagely three-roomed houses with an occupancy rate that in some cases exceeds three persons per room. 56% of the households who occupied houses that had less than four habitable rooms were tenants. Most of the tenants were in informal employment as maids, bus conductors, taxi drivers or employed doing piece works. Their monthly incomes vary from K120 ($55) to K2, 100 ($600) with an average of $325. Rent constitutes a major expense for tenants such that, to an extent it affects the expenditure on other important items such as food.

10. Conclusions

- Kitwe, like other cities in developing countries faces shortage of housing affordable to low-income households as the city experiences increase in economic activities. The city is expanding primarily through the development of new housing areas beyond the existing urban periphery in a relatively unplanned manner. The evidence from the research proved that, a large segment of the urban residents lives in rental accommodation in squatter settlements. The supply of informal rental housing built without following planning procedures or local authority by-laws is growing much faster than formal housing. The study further revealed that house-building in informal settlements by either landlords or informal residents takes place continuously as reflected in terms of the year of construction or redevelopment mostly without regard to planning rules or construction standards.Rapid urban growth is making more people reliant on informal rental housing for accommodation but housing production levels are not meeting demand either in terms of quantity or quality. Existing policies and laws do not cater sufficiently for the production of housing units, especially in the informal rental housing market. This market has become the most important sector in shelter production and will continue to provide the majority of housing units in Copperbelt towns in the twenty-first century. The informal rental housing sector is complex and problematic because it has not developed fully. It is currently dominated by small-scale landlords, most tenants are extremely poor and infrastructure and services are very inadequate. Informal settlements have become the dominant factor in the urbanization process and in the provision of housing for the urban poor. The settlements should not be viewed as part of the country’s housing crisis but rather as the urban poor’s contribution to its solution. The merit of rental sub-markets as observed from the research is that, they diversify the supply of low income housing, increasing the range of options available for poor households. Although not constituting ideal housing solutions, they certainly increase the possibility matching households’ needs in certain moments of their lives. Government of Zambia has little information about informal settlements since they are largely un-documented. Not having a clear idea of the size and income-demographic composition of a settlement’s population, or the characteristics of its housing stock, including the degree of overcrowding and sanitary conditions, makes diagnosing needs and prescribing effective housing policy more difficult. Though local authorities might have a good idea about the poverty levels and housing conditions of different neighborhoods, they do not have information on households that are most in need. There is also no legislation that provides for direction on improving the informal rental housing in Kitwe’s informal settlements. Some suggestions that can be considered by the local planning authority (Kitwe City Council) include the following:a) The Kitwe City council in consultation with real estate developers and other business institutions such as National Pension Scheme Authority (NAPSA), should open up new areas to encourage the investors to build affordable houses for all categories of income groups.b) Kitwe City council can consider initiating city expansion to the area of land across the Kafue River, south of the city. This will help to meet the high demand for land for housing. The current construction of a bridge across the river, which is being undertaken by the government can help to facilitate this process.c) Financial institutions should be consulted by the Kitwe City council to invest in real estate development to ease the pressure on peripheral land for the expansion as well as new evolutions of informal settlements.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML