-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2014; 4(3): 67-72

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20140403.01

Pre-eminence of Urban Culture and Apparent Conflicts amongst the Bengali Hindus in Kolkata

Golam S. Khan

Department of Communication and Development Studies, The Papua New Guinea University of Technology

Correspondence to: Golam S. Khan, Department of Communication and Development Studies, The Papua New Guinea University of Technology.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The East Bengal (EB) Hindu ‘refugee-migrants’ in their efforts to resettle in West Bengal (WB) experienced tacit cultural shock from the WB local residents who have similar religious, ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. This was a kind of Hindu-Hindu contradiction symbolically reflected in their attitudes of intellectual supremacy one over the other. The EB Hindus known as “Ruralites” (mainly agricultural backgrounds) having distinctive attitudes who could not easily socialise themselves with the local WB “Urbanites” (mainly city dwellers) of Kolkata metropolis. Neither the EB migrants took positive steps for their social adjustment with the WB society, nor did the WB locals extend their generic support for the migrants’ socialisation process during decades of post-migration phases of EB Hindus. This paper attempts to analyse the EB Hindus’ tendency of maintaining the continuity of their cultural traits amidst WB local culture in Kolkata. Symbolic construction of community and sustenance of regional-cultural boundary in their so-called “Ruralites-Urbanites” nexus will be counted in for a theoretical discussion.

Keywords: Refugee-Migrants, Family Values, Ruralites-Urbanites, Cultural-Regional Identity

Cite this paper: Golam S. Khan, Pre-eminence of Urban Culture and Apparent Conflicts amongst the Bengali Hindus in Kolkata, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 67-72. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20140403.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

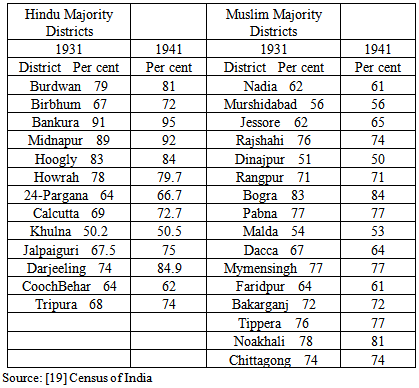

- The economic history of Bengal revealed the supremacy of the Hindu elites over the Muslims during the initial stage of the British rule, exploiting the majority poor Muslim peasants by the Hindu Zamindars in EB. In contrast, the Muslim League’s political authority in Bengal dominated the Hindus at large. This scenario hinted at a strong sense of majority-minority issues in two regions of Bengal. Since this study emphasized Hindu-Hindu cause, therefore, the security questions of the Hindu minority in EB prior to pre-partitioned India (1946-’47) contemplated historically significant.The second partition of Bengal indicated that the Muslims constituted an overwhelming majority in EB. On the contrary, Hindus were minority in Bengal as a whole, but they represented majority in WB. The Hindu and the Muslim majority districts of Bengal are shown below in Table 1.

|

2. Objectives and Methodology

2.1. Objectives

- The focal point of this research is to draw on the extent of contradictory relationships between EB Hindu migrants and WB Hindus in Kolkata. The primacy of urban culture in WB and its impact upon the most EB rural-agricultural migrants will be portrayed here.The major objectives of this research are as follows: • To discuss the Ruralites and Urbanites backgrounds of the EB Hindus migrants and WB local residents;• To analyze EB Migrants’ socialization process and resettlement efforts amidst the WB Hindus’ dominant metropolitan roles; • To find out the nature of symbolic differences between EB Hindu migrants and the WB Hindus under the purview of relevant sociological theory.

2.2. Methodology

- Primary and secondary data sources were utilized for this study. The primary data were obtained through fieldwork (Jadavpur-Bijoygarh are as south Kolkata) using qualitative research method including participant-observation, in-depth interviewing and case studies. The ethnographic characteristics of qualitative research and its legitimacy as qualitative interpretations of both traditional and post-modern perspectives were dealt in a number of ways, as for references [3]; [7]; [16]; [13]; [20] & [6]. In this qualitative inquiry, emphasis was placed on documenting EB Hindu migrants’ subjective expressions of facts, their struggle for resettlements and sustenance of regional- cultural boundaries. The secondary data were collected from available relevant written sources of all kinds including, books, journal articles, periodicals, research reports, unpublished dissertations, website references and so on.

3. Perception of “Ruralites and Urbanites” as Political Traitsand Social Variants

- In perceiving the uncooperative relations as social variants, the EB Hindus as ‘refugee-migrants’ and WB Hindus as local residents seemed to be politically motivated for establishing their own regional-cultural supremacy in West Bengal. EB Hindus as Ruralites and WB Hindus as Urbanites have supposedly contemplated themselves as two distinct communities tended to exhibit their lines of thought as critique to each other. Viewing power matrix as the strategy for emancipation, the EB Hindus were not only concentrating to regional identity, they were also explicitly demonstrating their point of variances towards political dispositions. This was how the politics of “Us &Them” or “We & They” developed between EB Ruralites and WB Urbanites in Kolkata. This distinctive character of opposing relationships in between communities could have certain relevance with the ‘power of ethnic nationalism’ [18]. Right at the beginning, the EB migrants were inclined to Communist Party of India, Marxist [CPI (M)] since this political party strategically extended substantial help and assistance to the refugee-migrants for their resettlement. Of course, they gained mass political support for their roles towards the refugee-migrants and hence consolidated political powers in WB for decades. On the contrary, the WB Hindus supported the Indian National Congress. This political party evidently disfavoured the EB Hindu migrants in various forms proposing them to return to their parental homelands amidst Muslim majority province of East Pakistan. Subsequently, they were having an idea of mitigating communal riots, just a utopian thought to many. Political partisanship of such nature created an uncongenial social environment for both the communities which in effect, limited their social interactions and widened further gap in between them. However, the economic viewpoint is significant in the assertion of political partisanship in general for both communities and in particular for the EB Hindu migrants. The emerging left-leaning politics of 'haves' and 'haves-not' in West Bengal extended explicit support to the EB Hindu refugee migrants as mentioned above. The pessimistic stances of the Indian National Congress towards the EB Hindus impeded their resettlement efforts in Kolkata to a considerable extent. Further, it was a great concern for the Indian national Congress that the number of non-Bengali residents in West Bengal became lower due to the huge influx of Bengali-speaking EB Hindu refugee-migrants. The question of balance of power and Indian Congress government's political domination over the state of WB became uncertain. Bengali-speaking population in Kolkata certainly has some politico-cultural implications beyond the so-called Ruralites and Urbanites conflicting scenarios. This political scenario was realised by both communities when they confronted non-Bengalis in Kolkata over economic interests. After three decades of coexistence, the whole range of relationships between the EB Hindu refugee-migrants and the WB local Hindus are therefore viewed more as symbolical than real. However, if this intricate fact (the politico-cultural impact of a Bengali-speaking majority) could have been duly considered, there would have been minimum controversy between EB Ruralites and WB Urbanites. While discussing social variants relating to EB Ruralites and WB Urbanites, some qualitative statements would reveal the attitudes to each other in a given social structure signifying more of a symbolical relationship.The following statements reflect the distinctions between East and West Bengalis (Ruralites and Urbanites) in pre-partitioned Bengal: East Bengal is the Scotland of Bengal. Whether we make fun of it or we criticise each other, there is a real distinction in nature and type; therefore, we should agree to differ than to be united. I have stayed here for a long time, but I have not found a single person, young or old or any student who showed interest in literature. I have never found such stark materialists…all that I say is about men. I do not know much about women. I think they are more hard working and intelligent than our women (West Bengalis) although they (East Bengalis) lack a bit of politeness. The family structure here is mostly joint-family, and has extended cohesiveness of human emotions in them. They are not weak, they are strong. They are expert in nursing and caring for people, but I do not know, maybe, they are not as devoted as our women who care for their husbands only [15].Following selected oral statements (gathered from the ethnographic fieldwork) show the attitudes of EB Hindu migrants towards WB local Hindus and vice versa. Statement-1 EB Ruralites and WB Urbanites are two different cultural communities regardless of Hindus or Muslims. Their distinctiveness will remain forever. After a long struggle of resettlement in West Bengal and interacting with the local people in economic, political, social and cultural activities, I must conclude, it is unlikely that the South Pole and the North Pole will ever meet [11].Statement-2WB Urbanites hide their true feelings by use of sweet words. They have dirty minds. They are jealous of EB Hindus materialistic endeavour and straightforwardness. They only know and have learnt how to take advantage for their self-interest. Despite their so-called aristocratic background, they are expert in sycophancy and cajolement for gaining their anticipated objective. They are never cooperative and helping. They only care for their own individual interests and nothing else [11].Above statements negatively criticized the local WB Hindus who constantly opposed any benefits that the EB Hindu migrants could get.In contrast to the above, the following statements by WB urbanites revealed their attitudes towards the EB ruralites: Statement – 3Criminal activities increased and bad politics developed in West Bengal due to the influx of refugee migrants from EB. I had bad experience working with different types of professionals from EB, particularly in public health services. Once an EB doctor who used to work with me in a medical centre, he also worked as a consultant in another health organisation simultaneously. One day that doctor reported to me that his name was included in that health organisation and that if he would simply visit there twice a week for one hour each day and signed the papers, he would get a good amount of money. The whole act appeared to me as immoral and criminal [11].Summary of statements:West Bengalis think of EB ruralites as rustic, uneducated, uncultured and corrupt. Even they cannot speak and pronounce Bengali language correctly. Conversely, the East Bengalis regard WB urbanites as lazy, crazy, miserly, unsociable, snobbish, having peculiar food habits and maintaining false vanity. Participant-observation and ethnographic accounts suggest that the overall attitudinal differences between EB Hindu migrants and WB local Hindus towards each other are more pronounced among older age groups compared with younger people.

4. Theoretical Perspective

- In weighing the social dynamics of EB ruralites and WB urbanites, their constrained relations, their intent of opposing each other in social, economic, and political activities, persistence of distinct identity and endurance of symbolic or realperimeter, the theoretical viewpoint of Cohen [4] can be treasured. Cohen [4] in his theoretical explanation of the symbolic construction of community and maintenance of boundaries stated that the word “‘Community’ seems to imply simultaneously both similarity and difference”.While observing the relationships between EB migrants and WB Hindus in south Kolkata, the notion of both similarity and difference applies. These two communities are similar in respect of language and religion but they are different in their regional identification and cultural practices. Hence, it is important to trace the development of theory around community which instinctively tends to maintain their limits by each community.The term ‘community’ is generally understood as the relationship between people who have common interests revealed as an intimate connection or harmonious community attachment. Initial conceptualisation of community relation shave developed in 1915, when Galpinvoiced of the ‘rural communities’ trade and service areas surrounding a village [8]. After this, a variety of definitions on community are enunciated: some are focused on community as a geographical area, some on a group of people living in a particular place, and still others consider community as an area of common living. Further, it is also stressed that there are issues around community which appear as political discourses [23]. Therefore, we can derive our theoretical understandings relating to community coherence and fragments in three different ways: firstly, the ‘place’ as territorial location; secondly, the ‘interest’ as sharing common interests, for example, religious beliefs like Catholic community, Muslim community or Hindu community and thirdly, ‘spirit of community’ which signifies a strong sense of attachment to a place or ideas. These relate to the spiritual beliefs and practices like the spiritual union between the Christians and the Christ, see for reference [5]; [10]; [16]; [24] & [25].Taking into account the cohesiveness and distinctiveness of the community attachments and separate identity of EB Hindu refugee-migrants and WB local Hindus, it would be quite conceivable to ponder the theoretical contribution of Cohen [4]. Irrefutably, once again a different approach in community relations that Cohen [4] has postulated as: …a relational idea: the opposition of one community to others or to other social entities. Indeed, it will be argued that the use of the word is only occasioned by the desire or need to express such a distinction. The EB Hindu refugee-migrants as a distinct community in Kolkata appeared to be hostile to the local WB Hindu community with their separate social entities and attitudes [17]. Likewise, the differences are observed among the local West Bengalis too. Thus a sociologically significant theoretical linkage can be established based on the above discussions; such as the way the EB migrants and WB permanent settlers describe and indicate their distinctiveness from each other.

5. Symbolical Sense of Social Dominance

- The variance of social domination indicates disproportionate access to power, status and wealth as material resources [22]. As such the sense of authority and domination are revealed in the form of subjugation and oppression. This is understood as asymmetric power exercised by the powerful and the powerless or the governors and the governed. However, an act of long-enduring powerlessness can create adverse consequences resulting in a state of irrationality and violence in society. Inevitably, it can lead to oppressed people aspiring for empowerment in the community [21]; [23] & [14].Reviewing the contrary relationships between the EB Hindu refugee-migrants and the WB local Hindus in regard to power and social domination, it seems all the more symbolic given the conflict and consensus way of interacting to each other. Their attitudinal inflexibility described as ‘Us and Them’, ‘We and They’, ‘Ours and Theirs’, and most importantly ‘Outsiders and Insiders’. All these self-willed notions of differences are symbolically constructed within two communities which have also rooted to politics of regionalism. The legal aspect of migrants becoming citizens during postcolonial phases in India has got more or less subjective explanation of facts. The EB refugee-migrants encountered specific social stigmas as ‘Outcaste’ or ‘Other’ in regard to supposed cultural limitations thereby having rural-agricultural backgrounds and non-exposed to urban metropolitan way of life on achieving their political citizenship status in India [9]. The bearers of dominant race, possessor of higher cultural norms and claimant of civilizational superiority can have citizenship status regardless of their migratory conditions. This kind of citizenship indicated the higher caste position of the migrants or economically affluent migrants. Primarily the proprietary rights, voting rights and right to participate in politics are considered as legal rights for citizens only. Legal rights further ensured the participation in religious, social, cultural and all other related affairs of the state. Hence, it is important to understand the role of citizenship, its meaning and usefulness in the context of migrants’ all out resettlement efforts for gaining legal-political rights in their new locations of habitat [14].

6. Discussion

- Following their past socio-economic milieu, it has been a commonplace that the most EB Hindu migrants were having rural agrarian and semi-urban backgrounds as against the comparatively more urban-industrial backgrounds of the majority local WB Hindus. Besides such a rural-urban specificity of the two communities, the relatively lower caste hierarchical position of the EB Hindus also made a clear distinction between them both at cultural and attitudinal levels [12].As opposed to urban-industrial cultural trend, the EB Hindus tended to maintain their unity in the process of their resettlement in the Udbastu colonies through retaining joint-family, endogamous marriage relationship, kinship ties and linkages. Contrarily, the WB Hindus commonly tended to maintain nuclear family ties and exogamous marriage relationships i.e., beyond regional identity. Surprisingly enough, the WB Hindus, in turn, insisted upon retaining caste identities/ hierarchies to a certain extent which appeared contrary to their nuclear and exogamous family preferences [11]. However, such outlook of family and social life did not remain static for the whole period since the partition of Bengal. After about three decades, such trend began to change when the EB Hindu refugee-migrants had been adequately exposed to ‘Urban-Metropolitan Culture’ and also been politically assisted substantially [11].To note that the EBH indus changing political status from refugee hood to citizenship affected their sociocultural and attitudinal levels of interactions with WB local Hindus. Consequently, a breakthrough has been noticed against a stereotypical regional identity issues. It has asserted an increase in the socialisation process of the EB Hindus for their adaptation with the WB Hindus. This change of status has significantly reduced the gap between two communities at cultural singularity. Therefore, it is fairly conceivable that the symbolic construction of communal-cultural boundary between EB migrants and WB Hindus attributed to forming a social reality alongside the domineering and conflicting relationships.

7. Concluding Remarks

- Foregoing discussions construed that the differing notions of Ruralites and Urbanites was symbolically constructed by both EB and WB Hindus for demonstrating their community identities. As such the symbolic construction includes conflicting relationships, the outer manifestations of the ingrained culture, social segregation [2] and also strategic political inclination and affiliations. In conjunction with the claimants of so-called urban city-dwellers (WB Hindus) having modern outlook, the explanations on problems of insiders-outsiders, attitudes of caste dominance and cultural supremacy can provide a better understanding of contradiction and conformity in between two communities under study. At the beginning of their socialization process and resettlement efforts, the EB Hindu refugee-migrants tended to maintain their regional-cultural boundaries in all possible ways. Then the differences seemed real against the WB locals who tried to demonstrate their cultural superiority over the EB migrants. The EB Hindu migrants thought it strategically expedient to resettle by maintaining a symbolic difference. However, the field observation suggests that over the years the extents of differences in all conduct shave reduced significantly. Currently, the Ruralites-Urbanites issue has a very little or no prominence to the younger generation of the WB local Hindus as well as the second-generation migrants.

Notes

- 1. ‘Refugee-migrants’ indicates the political status of EB Hindus who involuntarily crossed the Indian border as refugees and subsequently relocated in WB/Kolkata as migrants.2.“Ruralites” and “Urbanites” are two distinct groups of Bengali-speaking people of whom the East Bengalis are characterized as Ruralites” and the West Bengalis as “Urbanites” These two symbolic expressions of distinguishing rural-urban characteristics can be revealed idiosyncratically by their locality of residences, variations in their dialects, occupational identity and with their so-called statuses of citizens andrefugees.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML