-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2014; 4(2): 25-33

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20140402.02

Commoditization of Ritualized Occasion among Women in Northern Ghana

Adadow Yidana

University for Development Studies, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tamale, Ghana

Correspondence to: Adadow Yidana, University for Development Studies, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tamale, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The increasing participation of women in gift-giving is a wide-spread phenomenon in Ghana. This has culminated in the commercialization of ceremonies under which these gifts are. Using field data collected in Walewale in the Northern Region of Ghana, this paper reveals that gift-giving as practiced among women is part of their daily lives irrespective of their professional or social backgrounds. It depicts material and monetary investment in view of the fact that all beneficiaries of gifts have an obligation to reciprocate. What sustains women involvement (both rich and poor) in gifting is reciprocity. Consequently, the continued involvement of women in gift-giving enhances their social and economic statuses. In view of the continuous transmission of gifts during important occasions, the benefits as well as its relationship building tendencies, ritualized occasions are now commercialized.

Keywords: Gift exchange, Reciprocity, Commoditization, Commercialization, Investment, Social support

Cite this paper: Adadow Yidana, Commoditization of Ritualized Occasion among Women in Northern Ghana, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 25-33. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20140402.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Social life across societies in the world is governed by rules and regulations with regard to appropriate behaviour. An appropriate behaviour is relative and may be defined by people living within a geographical location. As a result, the daily life of people would become chaotic if laid down rules are not adhered to. In some societies, the moral and reciprocal aspects of gift transactions have long attracted theoretical interest in social science such as anthropology and sociology [10]. According to [11], gift-giving serves as a rock on which societies are built. In these societies, giving gifts function to establish, define, repair, maintain, or enhance interpersonal relationships, yet has been largely neglected by interpersonal scholars [17]. Be that as it may, it is important to stress that gift-giving as practiced in most societies, performs enormous functions, including among others social, cultural and economic. What is worth noting is that material and social communication exchange that is inherent across human societies plays an instrumental role in maintaining social relationships as well as expressing feelings that are relevant [17; 4]. According to [11], gift-giving denotes the notion of loan and credit between two groups or individuals. Others conceptualize it as a practice involving economic and social exchange. In this exchange process, resources involving goods, services, or cash, are what actors or givers and a receivers exchange [7]. Early studies on gift-giving showed that intangible and tangible material forms a central part of contemporary life in gift exchange [18]. Though a number of gift exchanges are intended to preserve social ties within a framework of ritualized ceremonies, many of them are economic. A ritual as used here is an often repeated pattern of behaviour which is performed at appropriate times, and which may involve the use of symbols. Going by this understanding, ritualized occasions are used here to denote key occasions under which gift-giving takes place. In societies where people face difficulty in accessing daily needs, occasions such as this are commoditized in return for gifts [5]. In very simple terms, a gift is something that is freely given for no return: something that is voluntarily transferred by one person to another without compensation. However, in ceremonial exchanges as anthropologists describes it, gift exchanges during ceremonies often lead to a cycle of reciprocal gift exchanges, thereby establishing some form of transactional relationship between parties involved [17]. Sustaining this relationship requires regular gift exchanges through which the practice is often re-affirmed by the actors involved. A recent study on gift-giving as a form of support conceptualizes gift exchange as an individual’s perception that he or she is loved, valued and could count on others should the need arise [19].It is important to point out that during gift exchanges; the manner of the exchange makes the participants feel they have not been supported after all, though literally, they may be seen to be receiving gifts [4]. This is because the support process in gift-giving is more often characterized as social exchange rather than a one way provision of assistance. In of the light of the processes involved in social exchange, there is often the desire to reciprocate. Social exchange theory is very useful for this kind of analysis due to its consistency with the current emerging issues in gift exchange. The theory posits that social support involves cost as well as benefits to actors who engage in gifting, and that givers make choices about what to give in the context of what they have. In line with this argument, explanations with regard to why sociologists find the application of the theory worth looking at, is that, a greater part of social life in Ghana is characterized by giving and reciprocating of material goods [18].According to [11], women who engage in gift-giving are often filled with the obligation to give, receive and to reciprocate. Consequently, gift-giving is a self-perpetuating system of reciprocity. It is important to note that the act of giving is superficially presented as a form of generosity, carefully staged, and seen as an obligation with a foundation of economic self-interest. Here, gift-giving is seen to be playing an economic function. On this note, gifts are perceived to be given and received on credit, or as means of trade [11]. One thing that has to be noted is that presenting gifts transmit the givers’ identity and shape the identity of the recipient [15]. It is however worth indicating that some givers are likely to be entangled in excessive one-sided giving, as is often the case between children and parents. Consequently, actions that provide backing to good intentions in gift-giving usually hinge on the type of established conditions under which these exchanges take place. Gift-giving thus, is a signaling device intended to create an economic value, and by observing reciprocity, actors create and maintain their economic interest, which allows them to meet their social needs [7; 4].Gift exchanges, it must be noted, create platforms for ceremonies under which gift exchanges take place to be commoditized. There has been a lot of study about the phenomenon of commodification [13]. Commoditization is a process by which a society dominated by the production and distribution of concrete use-values increasingly comes to reproduce itself through the production and exchange of commodities or, more precisely, abstract exchange-values [5]. As [16] has indicated the progress of commodification: ‘we sell what we think will sell instead of selling what we think should be sold’. For some time now, there has been a great spread of products being commodified, leading to the expansion of culturally related industries [13]. Several communities around the world have relented to the commoditization cultural expressions or ceremonies as it promised to be of economic benefit such as the creation of wealth among members [16]. Though most commodified cultural goods target only tourist, the commodification of ritualized occasions targets local people [8]. Interestingly, the commodification of ritualized occasion among women forms part of their daily lives. They undertake this practice to assist themselves. As [7] rightly indicated, women give the majority of gifts in many societies, either as individuals or as part of a group. Though givers and recipients may be individuals or corporate groups, exchange between individuals is perhaps the most common part of gift-giving [2]. Irrespective of the location of actors, and whether they are professionals or nonprofessional, efforts are often made to establish the desired relationships among themselves for the purposes of gifting. Despite the fact that these ceremonial gift exchanges speak volumes about individual relational perceptions and expectations, such behaviours have primarily been investigated by people outside the social sciences [19]. This development is surprising, in light of the prominence of interpersonal gift-giving behaviours throughout the relational lifespan (in families, in friendships, and between working colleagues). This paper thus provides an analysis of the commoditization of gift-giving among women and how it impacts on their economic and social wellbeing.

2. Objectives

- The objective of this paper was to explore the circulation of gifts among women during ritualized occasions in the Northern Region of Ghana and to explore how such ritualized occasions are commoditized. Part of the objective was to further determine the impact of gift-giving on the socio-economic wellbeing of women. This was necessitated by the fact that in almost all societies in Ghana, gift-giving remains an essential part of human activities, especially among women in the northern region of Ghana, where it forms a greater part of their daily lives. The practice of giving and receiving gifts is evidenced in the increasing activities of gift-giving during particular occasions. The intense gift-giving is found both in the urban and rural communities. The dynamism, seriousness and rapidity with which gift-giving is ritualized during these occasions makes it imperative for the emerging development to be monitored continuously, hence the importance of this study.

3. Methodology

- Between September and December 2013, a total of 100 women were engaged in an interview regarding their involvement in receiving and giving gifts to people who mattered to them. Of the 100 women selected, fifty (50) of them were professionals, drawn from the teaching profession, whereas the remaining fifty (50) were non-professionals, majority of whom were engaged in petty trading. A systematic random sampling technique was used in the selection process where two female teachers each from 10 primary schools and 5 junior high schools, all based in Walewale, the study area, in the Northern Region of Ghana. The selection was achieved by using a register containing names of teachers in their respective schools. In the case of the nonprofessional women, the selection was done in the market where they undertake their daily trading activities. The selection of this category was done using the arrangement of their sheds was used where every other shed was selected and the woman occupying it interviewed. In all cases, only the respondents who agreed to be interviewed were interviewed. Whilst the non-professional respondents were interviewed as they were going about their daily activities, the professional women were interviewed after they had finished with their teaching and other related duties. Selecting professional and nonprofessional women was to gain insight into different perspectives regarding the impact of gift-giving in their lives. Because gift-giving is tied to the existence of relations between the actors, only those who were resident in the town or at least had lived there for one year were interviewed. This consideration was taken because it is only residents who would have been able to establish social relations with others, leading to the giving and receiving of gifts. The research language was English and Mampruli (the native language) since majority of the people in Walewale speak English and/or Mampruli. Incidentally, all these are languages the researcher speaks. Interview guiding questions were used to elicit detailed information from interviewees concerning the gifts they give to, or receive from their relations. Each interview lasted between 25 and 35 minutes, and was recorded and later transcribed. For clarity, two focus group discussions were organized, one for nonprofessional women and the other for professionals to elicit additional information from them.

4. Discussion

- In many societies across the world, gifts presentations often mirror the occasions for which they are given. In view of varying interests in gift-giving, the concept has also been looked at from a variety of theoretical perspectives, focusing primarily on the functions of the practice to both givers and receivers [2]. The most fascinating and varied aspects of gift exchange involve the situational conditions under which the practice takes place. The varied interest in giving also creates a situation where different perceptions emerge in relation to large gift-giving occasions, especially those that have assumed ritualized character. The localized occasions that are ritualized include among others wedding, outdooring and funeral performance. In almost all communities in Ghana, these occasions come with celebrations during which family members and friends are invited [12]. As people attend, they try to show their worth through gifts. However, gifts are not just given; it is the occasion that dictates what is appropriate to be given. As a result, what a woman would give during a wedding ceremony is may be different from gifts she will give during a funeral. In almost all occasions, there are gift differentials symbolizing more than material attributes, and to give something to someone is to give a part of oneself [11]. In addition to all other interest, what women present represent their emotions, allowing them to communicate their feelings to the recipient without the use of verbal language [19]. In all occasions, the real motive of both givers and recipients is the achievement of a balanced reciprocity, which requires that the roles of these actors have to be reversed through time in order to maintain the exchange partnership. In the opinion of [1], the selection of gift to be given is principally based on the self-concept and intention of the giver and has little to do with the characteristics of the recipient.

5. Gift Exchanges - Are They Free?

- As a voluntary practice, gift-giving has evolved through time and cuts across many societies. Women engagement in gift exchange is subject to the benefit they seek to derive from their actions. It is worth noting that gift exchange may be seen as a rational act. Before any woman provides a gift to another woman, she takes into account, whether she will also have an occasion that would warrant reciprocity from the recipient [11]. The anticipation of return gifts motivates women to give with the expectations that recipients will reciprocate in the foreseeable future. During such ceremonial occasions as was observed among study participants, women who are conscious of the fact that they may also organize similar occasions, often try to present gifts to the deserving persons as a way of guaranteeing reciprocity. Apart from women with the potential to organize similar ritualized occasions, those who do not expect to have such occasion’s any time soon are motivated to present gifts as a way of preparing the grounds or investing for the benefit of their own daughters [5]. Giving someone a gift during an outdooring can be reciprocated during funeral rites. Consequently, qualification to give or receive a gift is based on the expected benefits of both the giver and receiver. It is a common knowledge among sociologists that the family and other social relations constitute an important part of the social process, and the act of gifting is governed by its own rules and regulations. Adherence to rules and regulations is one of the practices within the family that contributes to the transmission of values [12]. In many societies across Africa, most activities associated with the family revolve around women. The domestic role of women in this part of the world obliges them to receive gifts from other women as a survival strategy. Ghanaian women, it is interesting to note, find themselves in a dilemma. This is because tradition compels them to bear children. However, tradition does not exert similar pressure on men with whom they bear children to provide enough support for the mothers [8]. This, coupled with harsh economic conditions in Ghana has led to a situation where women have evolved strategies for coping with adverse conditions in which they live. During such occasions, beneficiaries of gifts are often elated with pride, simply because they feel they are living in communities where they are valued. In addition to the feeling of being valued, women also adopt other strategies including the formation of strong alliances and the establishment of mutual help of gift-giving and receiving with people whom they have established relations [8]. In deciding which gift to present, women pay more attention to the interest of the recipient as well as the occasion [11]. It is also important to note that during gifts presentation, relatives and friends of recipient are often called upon to witness the presentation and to know the identities of givers [8]. In many instances, these gifts are displayed ostensibly to boast of the material gains as well as the social network of the recipient. In effect, when women are attending such ceremonies, they go with other friends, some of who may not be related to the organizer. This is a normal practice, often done to boost their social standing and to get others to join the network of relations. It is important to state that all women with the potential to organize occasions of such nature are usually motivated to give ceremonial gifts so that others will reciprocate in the event that they organize some. As one respondent rightly indicated: We women are here to help each other. If you see that someone related to you is organizing an occasion, you give her a gift as a way of giving her your support. This is usually a show of concern, depending upon the occasion at hand. The above demonstrates some of the reasons behind ceremonial gift-giving. Some of them further explained that the common rational for presenting gifts is based on the principle of, ‘it is the thought that matters,’ reminding themselves about the fact that they value the gifts than their market value. Women who choose to present gifts do so hoping to convince the recipient that they spent time and effort in providing them such gifts. However, studies have shown that there are difficult gift recipients who may be perceived in that light by givers. In such circumstances, gift givers may characterize such recipients either as easy or difficult to give gifts. This kind of behaviour may stem partly from aspects of the relationship the givers express through the gift exchange [19]. As individuals receive, the same way they are expected to reciprocate. In as a result of the existence of norms governing most practices, the degree to which norms are adhered to in the exchange process are often stated in terms of what is known as distributive justice [17]. Distributive justice here refers to a situation where social rewards are proportional to both the cost and what is invested. Interestingly, women who engage in gift exchange are always conscious of the fact that what they receive as gift will eventually be reciprocated. As a result, women have to go through stress in meeting the obligation of return gifts. As [19] put it, the institutionalization of a gift occasion can trigger anxiety in the giver. It went further to show that the institutional influence in gift exchange occurs in two ways: in the first place, strict rules connected with such occasion trigger fear of rule violations, and secondly, institutionality signals the importance of the occasion and the necessity for gift success.

6. Commoditization of Ritualized Occasions

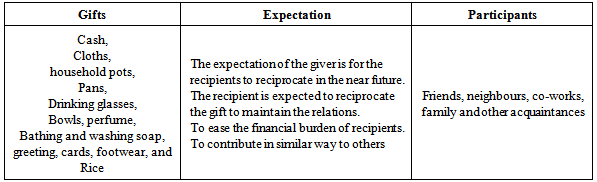

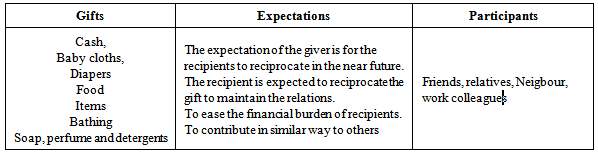

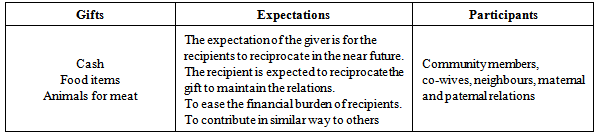

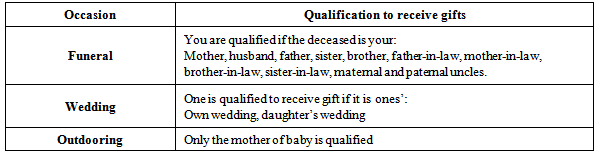

- In many parts of Africa as a whole and Ghana in particular, the way gift exchanges are conducted among women is akin to the way commodities are exchanged in a market place. Gift exchange among women are very pronounced during such occasions as outdooring of new born babies, marriage ceremonies and performance of funeral rites [8]. What has been noted is that during these occasions, invitations are sent round to all relations, informing them of the impending occasion. Traditionally, cola nuts used to be sent to people as a way of invitation. But in recent times, fewer people eat cola nuts, and so, cola nut is substituted for toffee for this purpose. However, there are others who would prefer invitation cards to cola nut or toffee. The use of invitation cards is however dependent upon the social standing of the person concerned. Once the invitation is sent, the invitee then decide what to present as a gift on the day of the occasion. With regard to the caliber of persons they invite, one of the participants indicated that: During such occasions, we make sure that all people whose occasions we have ever participated in are invited. Anyone coming to the occasion will come with a gift. If you do not invite them, some of them will return what was given to them back with a complaint that you do not want them to par take in your ceremony. Sometimes people we do not even invite will come to give a gift as a way of starting a relationship. I don’t mind giving help to anyone I know, because you know…., they will do the same for me in the near future. The above statement further explains why many women do not take gift-giving lightly. It is worth noting that different dates are often set, depending on the occasion. In the case of outdooring, the usual date is the eighth day after the birth of the child. On this day, all people who are related to the mother of the child and her husband, both men and women, partake in the outdooring or naming ritual [8]. It is this day that most gifts are presented. There is no particular order in presenting donations. Women who are not able to make it on the day of the occasion can present their gifts on a later date. Though some of the women would usually sell the excess gifts, some of them indicated they would usually prefer monetary gifts. As a result, women who are usually not certain about the appropriate gifts to give, as well as those who are yet to build a relationship with the recipient may decide to give money instead of buying goods as gifts. In the same vein, during marriage ceremonies, women present gifts to the bride as a sign of good will for her to start her new life as a married woman. Table 1, 2, and 3 below summarizes the occasions and the type of gifts that are giving to the recipients.

|

|

|

|

- As the tables above show, and as stated previously, the different occasions dictates different gifts and is determined through the conviction of the giver. During wedding ceremony for instance, gifts such as Cash, Cloths, household pots, Pans, Drinking glasses, Bowls, perfume, greeting cards, and footwear and Rice among others are giving depicting adult needs. In the case of outdooring of a new born baby, such gifts as Cash, Baby cloths, Diapers, Rice, Bathing Soap, and detergents among others are giving to depict the needs of the baby. In the case of funeral, gifts are restricted to food items, cash and animals for meat. These are given apparently to take care of the teaming mourners and to cater for other expenses. In all these ceremonies, a greater part of the responsibility in haven to ensure its success lies with women. They move to join their husbands in the case of northern part of Ghana, they are task to care for the babies are being outdoored and above all, they cook food and take care of other necessary things for the upkeep of visitors during funeral ceremonies. It is interesting to note that due to the material gifts that come the way of recipients, there seem to be some competition in the organization of these ceremonies. Some women could marry, divorce, and remarry ostensibly to accumulate more material wealth. Even when necessary, siblings could use one occasion to inform all their acquaintances and the proceeds from the visitors do not necessary go to the woman at the centre of the occasion. Another important observation is that most of the goods they receive as gifts are sold. Table 2 shows the occasions and circumstances under which one is qualified to receive gifts. If a woman loses her husband, father-in-law, mother-in-law, bother or sister-in-law, she stands to benefit from gift-giving. In the same way, if she loses her father, mother, sister or brother. If a daughter is marrying, as a mother, she will be giving gifts just as the daughter. The only situation where gifts go directly to only the mother is during outdooring.

7. Gift-giving – A New Way of Investment

- The main idea behind any investment is to reap one’s returns. Investment as used here refers to an individual’s commitment to use resources either monetary or nonmonetary, as gifts in anticipation that, some returns will be received over a specified period of time. Situating the process in the gift exchanges among women, the return on gifts usually come in the form of reciprocity [11]. As a practice, presentation of gifts helps a lot of women since giving gifts is akin to an investment. This goes to suggest that returns are reaped on the gift reciprocity. The more ceremonies there are for a woman, the more gifts she receives. What qualifies one to receive gifts is the presence of an occasion. Givers do not consider how many times they have giving gifts to a particular person. Once the occasion is genuine, gifts would definitely flow in, both material and nonmaterial benefits on recipient. It is a practice characterized by a high level of sociability, typically conceived of as an exchange that is non-exploitive.Though the above is true of what takes place among women, some women may violate the basic etiquette of reciprocal exchange by calling attention to their generosity, generosity that has to be reciprocated anyway. Consequently, the pressure to reciprocate under this situation is often greater than in other forms of reciprocal exchange. There are times that women do not want to be perceived as inferior [11]. To safe guide their reputation, recipients often strive to reciprocate. Failure to reciprocate appropriately can result in an asymmetrical relationship. The expectation is that reciprocal relations are established so that when there is any such occasions in one's family, they can cash in on their 'seed-money' or get returns on the resources they have given out. It on this note that [21] has elaborated on these prospective reciprocal relations in present-day urban Ghana, stressing on how widespread it is among women. The author stated that:Donations... compel reciprocal donations; habitual failure to attend funeral gatherings and make donations evokes its own punishment in the boycott of one's funeral performance by the community. This statement presupposes that for fear of been left unsupported or loosing ones social network, people are obliged to show their concerns through gift-giving. The fear has also led to an institutionalization of gift-giving; as a result, the whole process now depicts an investment since almost every woman is conscious of the situation. It is worth to noting that some of the gifts could take a short-term, or long-term to yield results. What determines the duration is the occasion for which one is presenting the gift. A woman can give gifts during funerals, outdooring or during wedding. A funeral could take a long or short term. This is because until someone dies, one cannot receive return gifts. The same can be said about wedding and outdooring. What need to be noted is that short term gifts or investment are those whose returns are immediate whereas the long term gifts are gifts whose anticipation of return are expected in a long term. Women who give gifts without any occasion in mind fall under the expecting long term return and seems to be consistent with [8] assertion that: In Ghana, for example, it is common that when young people receive support from older relatives…., they reciprocate by helping their younger relatives once they start earning money, rather than by repaying the person who helped them in the first place.The above suggests that the act of gift-giving can be generational and the returns can even be inherited by one’s children. An interesting observation with regard to this kind of gift-giving is the realization that people do not reciprocate by giving an exact commodity as the original gift. Returns on gifts are variable and do not come in exactly the same form. Even if the same gift is to be given, the quality has to increase. The change of gift or its quantity during reciprocity can alter the value of what is invested as a gift. On this note, it is also safe to speculate that these changes are made to minimize the suspicion that the same gifts was returned as was giving out. For instance, if Cecelia presents a wax print as a gift to Gloria, Gloria in reciprocating Cecelia will not necessarily present a wax print, but will look for a relevant substitute. If the occasion is outdooring, she will probably present about 3 to 4 baby wears.

8. Gift-giving as a Moral Obligation

- Morality in everyday life refers to how individuals’ deliberate about their moral responsibilities towards others. This is mostly done to assess what is appropriate behaviour and what is not in any giving situation. Morality in everyday life requires practical moral reasoning. It is important to note that in many parts of Ghana, especially northern region; hardship and scarcity are common themes among women. This probably explains the actions women take in either receiving or giving gifts [20]. Consequently, any support structure they develop may be guided by the moral principle of reciprocity. Invariably, the kind of support actors render to each other is demonstrated through sharing of both material and immaterial things. This is borne out of the fact that the burden of preparing food hangs on the shoulders of women. This responsibility has occasioned a situation where women have resolved to help each other during situations like this. However, it must also be added that, most of the people they receive as visitors present gifts as well. As [8] have indicated, women in their effort to live through their situational difficulties, form strong alliances and commercialized the occasions including its associated rituals. This practice has become an essential bargaining factor for many Ghanaian women in recent times. This is so because they use the ritualized occasions as a ‘one-shot-only’ flow of wealth. Considering their upbringing and socialization, women have a sense of moral obligation to their families, fellow women, neighbours, co-works, wider community, and distant others. It is important to indicate that they also do so as a show of sincerity and care. This observation is consistent with what a study participant in [20] has indicated that: ‘you got to help folks that help you.’ This statement presupposes that actions women take are embedded in a moral web of obligations and responsibilities. One thing that is apparent is that, social relationships consist of normative expectations and needs, and to abstain from making moral judgments is to be cut off from social relationships [15]. Human beings are interdependent and constantly help each other in one form or another; as a result, they often demonstrate a show of sympathy towards fellow-beings through the provision of support and assistance.In some instances, the actions women take in gift-giving are shaped by their personal qualities, dispositions and character in the social field that provide them the tools to strategize and improvise to accumulate economic and symbolic capital that enables them to render the help they provide [15]. Gift-giving among women is also a way of expressing support for others. These actions take place almost all the time, in both difficult and special situations. The satisfaction of all these ensures a lasting gift-giving amongst women.

9. The Socio-economic Impact of Gift-giving

- Another relevant aspect of gift-giving is its social and economic impact on women. This is due to the relation that exists between the price and quality of the gift [18]. This means that gifts can be used to create or maintain alliances with groups of women. During the field interview, some respondents pointed out that they join both professional and non-professional voluntary groups to benefit from gift-giving during ritualized occasions. Other observations are to the effect that the value women place on gifts they receive reflects the strength of the relationship they have with givers. Consequently, the quality and value of gifts reflects the changing nature of the relationship and reflects changes in the value of gifts. Through this, reciprocity is encouraged and social bonds forged [18]. It is interesting to note that the different statuses women occupy in society determine the gifts they present. As the case may be, reciprocity in gift exchange cannot be more balanced than are the respective social positions of givers and receivers. In addition to commodity gifts, women send their daughters to assist their colleagues at the centre of the occasions in the preparation of food and other domestic chores [8]. In view of the fact that they are conscious of each other’s occasions, a sense of belongingness is also created, where they help each other in times of need. Another important issue of importance is the fact that societies in recent times are driven by money. As a result, women have taken advantage of the situation to form associations that seeks to serve the interest of members. These associations are in classes and, depending on the social standing, one can either belong to the association of the rich, whose presence in any given occasion is always visible, or the poor whose presence may not be felt. During wedding or outdooring, members of these associations are often seen in convoys either in vehicles or motorbikes. During such occasions, recipients are often overwhelmed by the gifts. To keep track of the people who present these gifts, they write down names of all the gift givers, and what they give. The records are used as references, so that when it is time for them reciprocate; they will know what to give. One interesting observation is that women rarely reciprocate with exactly what they have been given.

10. The Psychological Impact of Gift-giving

- One of the factors believed to be involved in the likelihood of people becoming ill-either physically, mentally, or both – is lack of support from other people [14]. Social support as a concept has its origin in Durkheim’s emphasis on the role of social integration in his study of suicide. This go to suggest that the kind of assistance women receive from their peers helps them guard against adverse life events. In the same way, the absence of such support systems might also expose them to increased stress. As has been noted earlier, one aspect of gift-giving is the establishment of social relation. Thus, one key psychological impact of gift-giving is the feeling of being valued and loved by others. Support of this kind serves as a direct and positive influence in promoting good health. Another realization is that gift-giving act as a powerful mediating factor in a range of physical and mental health problems [6]. It is however important to make a distinction with regard to social support. This involves making a difference between the availability of the support, perceived support and the delivery of support when it is most needed. For instance following a major life event, such support can act as a direct and positive influence in promoting good health. Another aspect that is of interest is the fact that, though people give gifts out of generosity, at the individual level, gift giving reflects the perception of givers and recipients regarding the identity of oneself and the other. Study conducted by [1] indicates that individual projection of an ideal self-concept takes precedence over actual self-concept and perception of receiver in both gift selection and symbolic encoding of gift by the giver. As [17] has indicated, gifts constitute one of the ways through which the pictures that others have of us in their minds are transmitted. This goes to suggest that women reveal who they are to their relations through the gifts. The characteristics of the gift itself act as a powerful statement of the giver's perception of the recipient. What this suggests is that acceptance of a particular gift constitutes an acknowledgment and acceptance of the identity the gift is seen to imply. It is also worth noting that gift giving impacts positively on the well-being of the individual receiver, especially so during funerals, when death rarely announces its presence. As one of the respondents has indicated: When my father died, I had no money to undertake the funeral rites as is always expected. But because of what I did for other women during occasions of such nature, I was giving lots and lots of gifts as a token of support. It was this that helped me go through the whole episode without been embarrassed. Unlike western countries where funerals are managed by funeral contractors, in Africa and Ghana for that matter, it is a community and family affair. People come around to mourn with the bereaved, as they mourn, they eat and bath. In many instance, women weep not because they have lost a love one, but how they are going to cope with the burden of catering for the large number of people who are likely to partake in the funeral. To such people, gift given is seen as a blessing since it serves to take the burden of providing for the guest off them. In a like manner, there are those who become elated when such occasions take place as it turns to boost their economic potential. This is especially so for women who have no relation but have to receive gifts because of their relationship with the deceased or people organizing the occasion. This explains why some women will not be happy if women they have ever presented gifts to, fail to reciprocate their generosity. To others, occasions of this nature enables them to make wealth. This confirms [8] suggestion that such practices are ways of accumulating wealth. Even if they are not directly involved and the occasion has to do with a distant relative, as a way of getting what they give out back, they will invite all people whom they have established acquaintance, ostensibly to get them to give them gifts. Gifts women give to their fellow women with whom they have acquaintance includes baby wears; bathing soap, wax prints during outdooring. Though some women do it individually, others do it in groups, depending on the number of associations the beneficiary belongs to. In the same way, during wedding, there are gifts presented to the bride by women from her community, and associations she herself belongs.

11. Conclusions

- The act of giving and receiving gifts plays a major role in the lives of women in Ghana, particularly in the northern region. The paper explored the impact of gift giving on the lives of women. From the data analysis, the paper reveals that gift-giving is now institutionalized among women. Women give gifts in order to establish social relations with other women. The data also revealed that the occasions under which gift-giving is practiced have turned the occasions into commoditize through which they make wealth [13]. It further indicated that reciprocity plays a vital role in the sustenance of gifts among women. In view of the realization that the gifts women give are supposed to be reciprocated, the practice is likened to investment, in both monetary and material terms. Apart from the socio-economic and psychological benefit of gift-giving, the practice reinforces relationships among women for as long as they continue to give or reciprocate [11]. The network an individual woman establishes reflects the number of gifts she receives during giving occasions. This often comes with pride. Thus, people turn to present gifts to friends of their friends even if they barely know them. In view of the relation between established relations and gift giving during occasions, the process will continue to influence more people to continue giving as well as establishing new relations.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML