-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2013; 3(2): 36-45

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20130302.04

Child Poverty in Uganda: Analysis of the UNHS 2009/2010 Survey

Gideon Rutaremwa

Center for Population and Applied Statistics, Makerere University, Uganda

Correspondence to: Gideon Rutaremwa, Center for Population and Applied Statistics, Makerere University, Uganda.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Understanding the extent and characteristics of child poverty in Uganda is vital for policy and programs aimed at addressing it. In addition, child poverty eradication would lead to all children enjoying their rights, reaching their full potential and to participating as full members of society. Data used in this study were from the Uganda National Household Survey – 2009/2010. Although this was a national survey covering 6,800 households, this paper utilizes data from 20,045 children of age18 years and younger, to provide analyses of child poverty in Uganda. In the analysis, three logistic regression models were estimated, predicting the odds of a child being severely deprived of education and health and finally falling below the poverty line. Child poverty was conceptualized both in its narrow definition to imply resource deprivation terms and was measured in relation to the proportion of children severely deprived of basic human needs including: education and health. On the other hand, the poverty line definition was adopted and used. The study shows that the proportion of children living below the poverty line was higher compared to the national average. In addition regional differences existed in the level of poverty: severity of education and health deprivation. The number of persons living in the household where a child was resident was directly associated with the likelihood of a child being poor. Other factors affecting the level of poverty among children included; rural-urban residence and sex of child.

Keywords: Child, Poverty, Uganda, National Household Survey

Cite this paper: Gideon Rutaremwa, Child Poverty in Uganda: Analysis of the UNHS 2009/2010 Survey, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2013, pp. 36-45. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20130302.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Poverty is a condition usually characterized by a severe deprivation of basic human needs[1]. It is estimated that one third of all children in developing countries (approximately 674 million) are living in poverty, the highest rates being in the rural areas of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (over 70%). Children are often viewed as having no personal responsibility for their own economic situation and since the negative consequences of child poverty for both the individual and society may be quite large[2][3][4]. Given these perspectives, therefore, child poverty has often been viewed in the broader spectrum of child protection. However, this is a difficult and complex area in social work practice and the decisions made by social workers and other practitioners may have a significant effect on the well-being of children and their families[5].Studies related to poverty often subsume children within the poverty categories most often referred to such as households, communities and people. The latter implies that there is a high tendency to focus on adult-related poverty while child poverty is ignored, partly because children have little power and influence within a group that contains adults. Poverty in the household often has far reaching impacts on the welfare and security of children. For example, much has been written about the relationship between socioeconomic status and child abuse and neglect. It is well documented that children from poor families are overrepresented in the child welfare system[6]. Poverty is an important factor in child protection caseloads in other countries as well. In their discussion of ecological factors in child abuse and neglect in the UK Spencer and Baldwin[7] identify the strong correlation between poverty, low income and child maltreatment. They referred to a study by[8], who found that 57 per cent of children in their sample had no wage-earner in the household. In the USA, researchers[9] in their analysis of the child welfare data in Missouri, found that the critical variable for children coming into care was poverty.A few studies written about child poverty in Uganda have come up with, some conclusions concerning the role of social protection programs, mechanisms for addressing child poverty including community and local level interventions and the need for a research agenda all geared at reducing child poverty[10]. In a related study by[11] on children in abject poverty in Uganda suggests simple criteria for recognizing children in abject poverty, as opposed to a sophisticated one. They add that top on the list should be absence of basic necessities such as shelter, food, clothing and water. However, equally important are the ‘human condition’ in terms of physical health and parental care and protection. The latter observations resonate well with similar studies in both developed and developing countries[12][13]. The dynamics of child poverty have important policy implications, notably, chronic poverty may call for a different policy response than temporary poverty, and the identification of key negative events that consistently push children into poverty may signal undesirable weaknesses in the public safety net[13]. Furthermore, by following children (and their families) over time, we can determine whether policies should, perhaps, be tailored according to the age of the child, since most families have a particular income and career life-cycle pattern. Thus, information about the dynamics of child poverty may help us construct more salient policies for fighting child poverty.The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the understanding of child poverty in Uganda by using data from the Uganda National Household Survey - (UNHS 2009/2010) to provide basic results concerning the child poverty among the Ugandan population. The use of the UNHS 2009/2010 data is very useful, among others, for the study of child poverty, because this survey was nationally representative. By providing adequate information on households and individuals in these households, the data offers a useful opportunity for analysis of child poverty in the country, which impacts on their capacity to overcome difficulties. This study is important because children under 18 represent the largest group of the poor in Uganda[10]. Besides, child poverty, to-date, has not been adequately incorporated in the many poverty analyses which have been carried out. First, we examine the framework with which we approach child poverty and how UNHS 2009/2010 survey data documents child poverty. Then, we shall analyse these data to illustrate the case for Uganda, and discuss the results obtained.

2. The Dimensions of Child Poverty

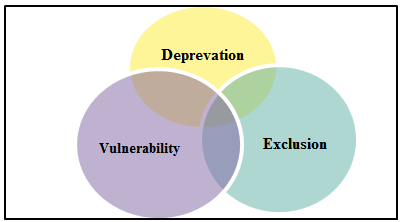

- Throughout this paper, we use deprivation as opposed to income-based measures of poverty other measures based on expenditures and/or consumption. There are several good reasons for this, but more importantly, this aspect captures the severity, intensity and contextualized nature of children’s experiences of impoverishment with regard to their material conditions and access to basic services[14]. Children living in poverty are invariably deprived of nutrition, water and sanitation facilities, access to basic health-care services, shelter, education, participation and protection. It is most threatening and harmful to children, leaving them unable to enjoy their rights, to reach their full potential and to participate as full members of the society[15]. The DEV child poverty framework[14] posits that child poverty is composed of three dimensions: Deprivation, Exclusion and Vulnerability, which together capture the broad spectrum of experience of child poverty. This paper will be concerned with only one segment of this framework, the deprivation dimension of child poverty.

| Figure 1. The DEV Child Poverty Framework[14] |

3. Data and Study Context

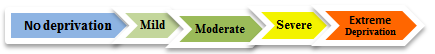

- In this study, we use data from the Uganda National Household Survey - UNHS 2009/2010, which allows us to track the individual child record within the household. The UNHS 2009/2010 is part of a series of household surveys that started in 1989 in Uganda. The survey collected information on socioeconomic characteristics both at household and community levels as well as information on the informal sector. The main objective of the survey was to collect data on population and socioeconomic characteristics of households for monitoring development performance.The economic characteristics and household structure are used in this paper only to account for part of the daily life of children who are often affectively and economically linked to other neighboring households. The household, on which these results are based, represents the visible part of a wider social system that certainly deserves to be better understood[16][16][17] and that would necessarily have to be taken into account to have a full view of child poverty, no doubt, poverty does not stop children from hoping, nor does it prevent them from enjoying certain other aspects of their lives, their household and communities[14].Nevertheless, the analysis in this study hinges on the basic hypothesis that the household is a relevant unit for studying the living conditions of children. Comparable definitions of the household lead to comparable data. Even though data procedures have a tendency of defining the household as the smallest unit in any ambiguous case[18], this unit obviously cannot capture the entirety of the social network around a person; it provides information on the closest persons around the child. This physical proximity should not overshadow the quality and intensity of other relationships in a broader social network, like relatives sending remittances or visiting regularly, yet it actually accounts for daily contacts and potential care in case of event of threat. We therefore assume that living together provides more physical and emotional support than mere physical proximity, a frequently used starting point[19][20].Another limitation of the use of household characteristics to assess the immediate contact circle on which a child can rely is its flexibility over time. The image of domestic structures given by cross-sectional demographic surveys is a fixed image, while household structure changes over time and adjusts according to needs and opportunities[21]. The purpose of this study is partly to point out situations where issues related to child poverty are evident. In order to measure absolute poverty amongst children, it is necessary to define the threshold measures of severe deprivation of some basic human needs for: food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education, information and access to services. Figure 2 presents the continuum of deprivation.

| Figure 2. The Continuum of deprivation[22] |

| (1) |

4. Results and Discussion

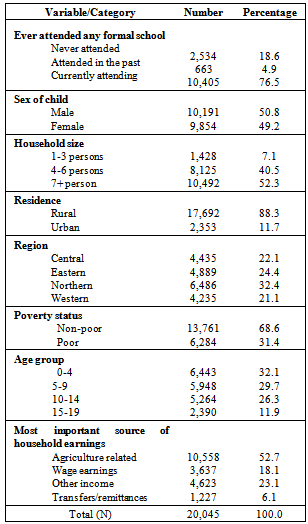

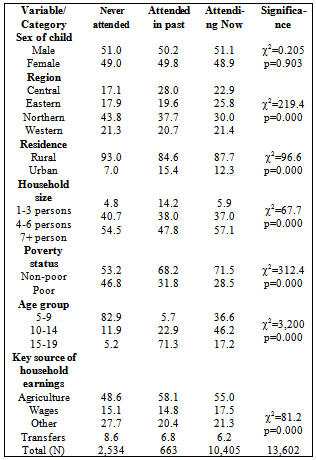

- The analysis starts with presentation of the characteristics of the children below the age of 18 as presented in Table 1.The descriptive statistics presented in Table 1 suggest that nearly one fifth of the children (18.6%) had never attended school this proportion does not vary significantly among boys and girls. Similarly slightly more than three quarters (76.5%) of the children less than 18 years of age were currently attending school. The study population comprised 51% male and 49% female. Given the broad base structure of the Ugandan population, the majority of the children were of ages below 10 years (62%).In terms of residential characteristics the findings presented in Table 1 show that 88% of the children were from rural households, with only about 12% urban. The regional distribution indicates that the Northern region of the country was fairly better represented in the sample (33.4%) compared to other regions and that Western Region which had the least numbers comprised only 21% of the study population. Given that the majority of the children hailed from rural areas where household sizes are large, the majority of children belonged to households of seven (7) and more persons (52.2%). Only 7% of the children were from small households of less than four children.

|

|

|

|

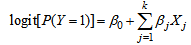

5. Multivariate Analysis

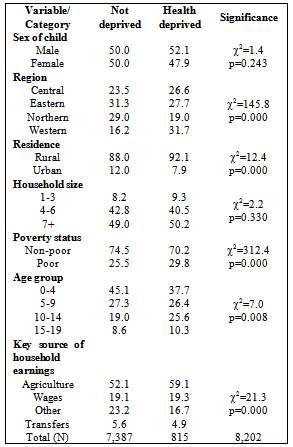

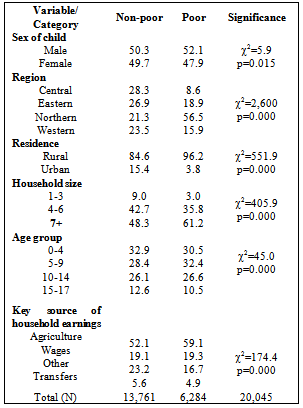

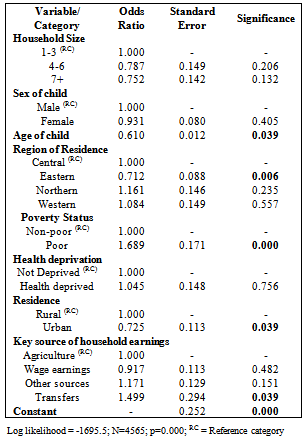

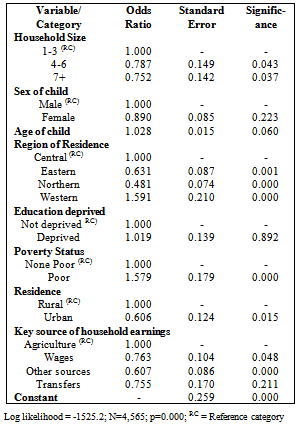

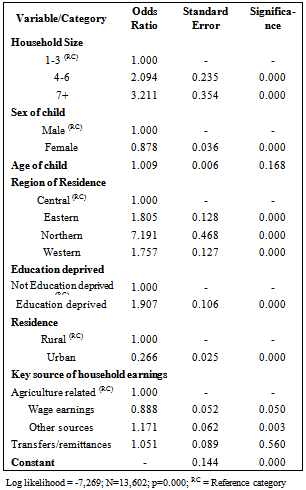

- This section presents findings from the regression analyses where first the two forms of deprivation: severe education deprivation and severe health deprivation are examined. The second sets of results pertain to the variable poverty, defined as households who lived below the minimum daily caloric requirements as presented in Table 7. The findings presented in Table 5 show that only a few variables was significantly associated with education deprivation among children in Uganda. Notably household size and sex of child were not significant in the regression models. However, a significant association was observed between age of child and education deprivation. The log-odds of a child being severely education deprived were inversely related to the age of child (OR=0.610; p=0.039). The latter implies that as children grow older their likelihood of being enrolled in school tends to increase.The results in Table 5 show that each unit increase in the age of the child was associated with a 35% reduction in the odds of the child being severely education deprived. The implication for this finding is that as children grow older, they are more likely to enrol in school. This can be attributed to the existing government sponsored universal primary education (UPE) and universal secondary education (USE) programs, which among other issues tend to promote school enrolment among children. Concerning region of residence, the likelihood of a child being severely education deprived reduced significantly (OR=0.712; p=0.006) if the child was from the Eastern region of the country compared to the Central region. However, there was no significant difference in severe education deprivation between western, Northern and Central regions of Uganda. The seemingly low severe education deprivation in Eastern region compared to Central region can partly be attributed to the socioeconomic and political dynamics in these various parts of the country that are either supportive or otherwise negative. The findings in Table 5 further suggest that children from “poor” household were as expected more likely to be severely education deprived compared to those from non-poor households. The results show that the odds of a child from poor household being severely education deprived were twice as much compared to those of a child from a non-poor household (OR=0.524; p=0.000). This finding is particularly disturbing and implies that even with free education under the UPE program; still the poor cannot access education. Furthermore, the results suggest that children residing in urban areas had reduced odds of being severely education deprived compared to those from rural areas (OR=0.725; p=0.039). Finally, it appears that children from households where the most important source of earning was from the transfers including remittances, had increased log odds of being severely education deprived (OR=0.405; p=0.039). If this latter result is not a mere artefact of data, then it presents a contrary view to the theory of “economics of new migration”. Concerning children’s education, the argument often put across is that transfers and remittances ably contribute to significantly financing education of children in the remittance receiving households.

|

|

|

6. Conclusions

- Given that this study is an initial attempt to explore the factors associated with child poverty in Uganda, it is difficult to make clear policy recommendations at this point. However, a few policy implications emerge from this study and can be confirmed by additional research. First, the proportion of children living in poverty is higher than the national average. This suggests that targeted programmes aimed at up lifting the conditions of children should be put in place. Such programmes should focus on children who come from poor rural households. In terms of severe education deprivation, Eastern region should be the region of focus, while Western region and Central regions should be the focus for regions of health interventions among children under 18 years. Second the analyses suggest that children who live in households with more persons are more disadvantaged and are particularly at risk of being poor. Public campaigns and social policies designed specifically to promote a small family size norm could prove effective in reducing poverty among households and among children ultimately. Such interventions could target households whose main sources of livelihood are agricultural related earnings. Invariably most such households are found in the rural settings of the country.Third, the investigation found that the boy children are more likely to be poor compared to their female counterparts. However, this finding was not conclusive, given that the analysis in this study did not find female children to be better off when it came to severe education and health deprivation. Further research is therefore necessary to make this determination and also to account for the other indicators of poverty among children that were not captured in the data set used in this study, the UNHS 2009/2010. Finally, an improved understanding of issues related to child poverty would go a long way in improving the social policies, ultimately reducing child poverty and otherwise deprivation of various needs among children including health and education. Future investigations could also address other components of child poverty such as sanitation, shelter, nutrition, information and access to basic services. Therefore, replicating and expanding studies of this nature could be a useful contribution for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to thank the French Institute for Research in Africa (IFRA) for the financial support under the ANR EVEPJVAE project that enabled the preparation of this paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML