-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2013; 3(1): 1-5

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20130301.01

The Effect of Household Characteristics on Child Mortality in Uganda

Allen Kabagenyi1, Gideon Rutaremwa2

1Department of population Studies, Institute of Statistics and Applied Economics, Makerere University, Kampala, UGANDA

2Center of Population and Applied Economics- CPAS, Makerere University, Kampala, UGANDA

Correspondence to: Gideon Rutaremwa, Center of Population and Applied Economics- CPAS, Makerere University, Kampala, UGANDA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of this study was to establish the relationship between household characteristics and mortality among children under the ages of five in Uganda. Uganda in 2006experienced a high infant mortality rate of 76 deaths per 1000, far above the world’s average of 52 deaths /1000 live births. Of the infants that survive to the first birthday, 67 out of 1000 died before reaching their fifth birthday. In order to address this problem, the authors used survey data on 4,169 women respondents drawn from 14 districts of Uganda where the Uganda Ministry of Health intended to implement the Health Sector Strategic Plan II (2005/06 – 2009/10). Brass-type indirect techniques for mortality estimation were employed to establish the mortality rates. In addition, logistic regression analysis examined factors related with child mortality. Findings show wide mortality differentials by household type, place of residence, and household size. Mother’s education and children ever born were the two major variables highly associated with child mortality. The study concludes that household structure was not related to child mortality. There is need for adult literacy, secondary and above education for women and sensitization about the effects of large households and children ever born. Such studies provide insight into understanding the relationship between various household characteristics and child health outcomes.

Keywords: Household, Characteristics, Child, Mortality, Uganda

Cite this paper: Allen Kabagenyi, Gideon Rutaremwa, The Effect of Household Characteristics on Child Mortality in Uganda, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2013, pp. 1-5. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20130301.01.

1. Introduction

- More than 10 million children are said to be dying each year in the developing countries the vast majority from causes of easily preventable diseases. In low income countries, one child in 11 children dies before reaching its 5th birthday compared to 1 in 143 born in high income countries[1]. According to under-five mortality estimates in the world, Uganda was ranked 27th among the leading countries with a rate of 90 deaths per 1000 live births[2]. The rates are similar to the current Uganda demographic and health survey estimates of 2011 which indicated that over 90 children out of 1000 live births die before their fifth birthday, while 50 infants out of 1000 die before their first birthday[3]. Given the prevailing country’s mortality rates, the 2015 Millinium Development Goals is unattainable[3-6]. Reduction of these rates to the least figures is pertinent to the well-being of these children. Although the rates are still high, most of the leading causes of deaths among the under-fives in the country are easily preventable and related to public health seeking behaviours. The vast majority of deaths are due to malaria, perinatal and early neonatal conditions, meningitis, pneumonia and HIV/AIDS[1, 2, 7].Children are the most vulnerable groups of people that are subject to the risk of deaths as a result of diseases related to socio-economic and cultural factors of the households[3, 8, 9]. Research has shown that a household is a micro unit of production, reproduction, specialization, association, consumption for the society as well as a fundamental and socio-economic unit in country[10, 11]. In Uganda the average size per household is five people and it varies across all the regions[12]. In most cases the size and composition of households depends on the demographic, social, cultural and economic conditions in a respective area[13]. Traditionally, large households with many siblings were considered to be prestigious and as a source of sustenance in old age. However, this exposes children to the risk of death given the economic constraints of large households[10, 14]. This is because the capacity of a household to adequately meet the needs of all the members is affected by household structure comprising household size, household type, number of children ever born and place of residence among others[15, 16]. Bronte-Tinkew and Hewett[17] examined the link between household structure, household economic status, child well being and found that household structure, not necessarily household economic status, would affect the wellbeing of a child. Though the question of household structure remains a problem, there are no adequate explanations for the relationships between child survival and household characteristics. This paper examined the relationship between child mortality and household characteristics in 14 districts of Uganda.

2. Methodology

- This paper uses a data set based on Support to Health Sector Strategic Plan (SHSSP) survey of July 2004. The survey was carried out on a sample of 7600 households in 14 districts of Uganda with a 95% response rate. The districts where SHSSP study was conducted were Arua, Adjumani, Apac, Kaberamaido, Moyo, Soroti, Kapchorwa, Katakwi, Nebbi, Mubende, Bushenyi, Bugiri, Lira and Yumbe. The districts were chosen by the Ministry of Health (Uganda) for being disadvantaged in terms of health issues, infrastructure and socioeconomic development. The survey used both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection aimed at providing basic data for the development of the national communication strategy for the provision of the National Minimum Health Care Package. Data used for analysis in this paper was based on information on all births and deaths that had occurred five years prior to the survey data. Statistical package for social scientists (SPSS) and STATA ver. 9.0 were used for extraction and the eventual analysis of data. Descriptive statistics and frequencies of the background characteristics of the mothers and the respective households the children belong to were generated. The association between the independent and dependent variable was established using chi-square analysis procedures. The dependent variable selected was the outcome of a question asked whether a child born alive in a household had died or survived. The independent variables included children ever born, household size, residence, type of toilet facility, source of drinking water and mothers’ characteristics including; education, religion and age. A critical level of significance of 5 percent (p<0.05) was used to identify the most statistically significant determinants of child mortality at the household level.Estimates of infant and child mortality were obtained for the overall study districts. Indirect techniques of childhood mortality estimation based on the Brass type of indirect procedures[18] were employed to estimate the probabilities of dying for children in the program districts. Mortality estimates and differentials studied herein are for the study areas not by districts. The procedure employed is expressed as follows:

| (1) |

is the probability of dying between age x to x+n

is the probability of dying between age x to x+n is the multiplier for conversion of proportion dead to probability of dying at the age x and

is the multiplier for conversion of proportion dead to probability of dying at the age x and  is the observed proportion of children dead in the population[14].Furthermore, the north family model life tables were used because they were found to be suitable for Uganda. The Brass procedure used herein allows for the estimation of the reference period which mortality estimates SHSSPS data set had. This was important because it affords us the opportunity to examine the trends in the infant and child mortality. The binary logistic regression model was used to study whether the independent factors affected a child chance of surviving or not. The parameters of the model were estimated using the maximum likelihood method as shown below in the formula;

is the observed proportion of children dead in the population[14].Furthermore, the north family model life tables were used because they were found to be suitable for Uganda. The Brass procedure used herein allows for the estimation of the reference period which mortality estimates SHSSPS data set had. This was important because it affords us the opportunity to examine the trends in the infant and child mortality. The binary logistic regression model was used to study whether the independent factors affected a child chance of surviving or not. The parameters of the model were estimated using the maximum likelihood method as shown below in the formula;  | (2) |

| (3) |

= is the error term The odd of an event is the probability that it would happen to the probability that it would not occur and the likely number of times. In this paper it is the probability that a mother will lose a child to the probability that the person would not lose one. This means that the outcome variables in the logistic regression should be discrete and dichotomous. Logistic regression was found fit to be used because the outcome variable was in binary form that is a child born alive survived or otherwise died. In addition, there were no assumptions to be made about the distributions of the explanatory variables as they did not have to be linear or equal in variance within the group. The model suggests that the likelihood of a person to losing a child varies across all the independent variables to be studied. After fitting the model, the outcomes were used to interpret the existing relationships between ones’ child survival, household structure and mothers characteristics.

= is the error term The odd of an event is the probability that it would happen to the probability that it would not occur and the likely number of times. In this paper it is the probability that a mother will lose a child to the probability that the person would not lose one. This means that the outcome variables in the logistic regression should be discrete and dichotomous. Logistic regression was found fit to be used because the outcome variable was in binary form that is a child born alive survived or otherwise died. In addition, there were no assumptions to be made about the distributions of the explanatory variables as they did not have to be linear or equal in variance within the group. The model suggests that the likelihood of a person to losing a child varies across all the independent variables to be studied. After fitting the model, the outcomes were used to interpret the existing relationships between ones’ child survival, household structure and mothers characteristics. 3. Results

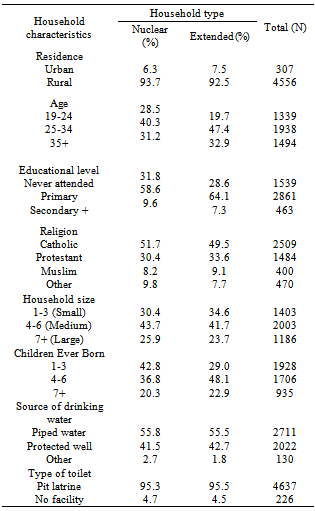

- The results of the analysis are presented in Table 1. The table shows most of the respondents were from rural areas irrespective of whether the household was nuclear (94%) or extended in nature (94%). The majority of the respondents belonged to age group 25 to 34 years, with extended households having slightly higher percentages (47%) than nuclear households which reported only 40 percent. More than half of the respondents who participated in the survey had been to a formal school. The highest percentage for educational level attained was primary with (59%) and (64%) for nuclear and extended, respectively. Majority of the respondents were Catholics with 52 and 50 percent for nuclear and extended households, respectively. Nearly all households had access to safe drinking water and toilet facility. Nuclear households had 1-3 children born (43%) more than extended households (29%).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

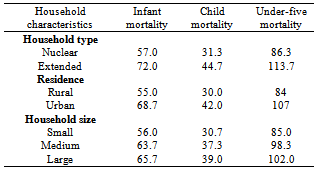

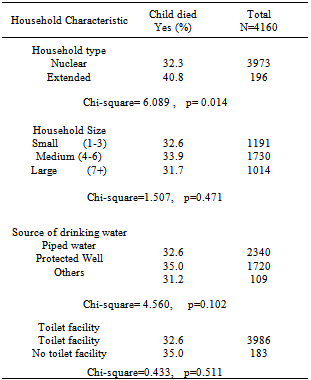

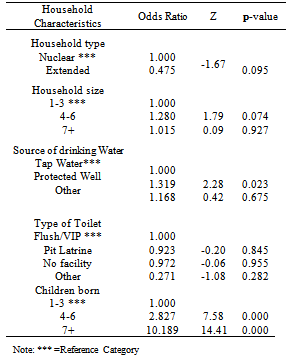

- It is not surprising that mothers’ characteristics were found to be significantly associated with whether a child that was born alive had survived or later died. Characteristics of the mother found to be associated with child survival at Bivariate analysis level were; household type, religion, education, children ever born and age of the mother. The association between the socioeconomic factors on child mortality has been explained in the Mosley-Chen framework[3, 8, 25]. This further explains the direct impact of some back ground characteristics of mother have on her child’s survival status. Indeed household type plays a significant role in child survival status, in that children born in extended households were more likely to die than their counter parts. This is so true given the socio-economic constraints of large households[10]. This was also confirmed with the mortality estimates generated using Brass techniques which presented children born in extended households having a high risk of death. There were mortality differentials recorded for household size, as children a nuclear household were more likely to survive. Unexpected though were the household characteristics like place of residence, type of toilet facility and source of drinking water were found not to have any statistical association with whether the child born alive died or otherwise. These findings contradict with the other findings of[15, 26] who examined the contribution of household environment to urban childhood mortality. These found that children whose mothers lived in households with no toilet facility as well as source of drinking water had a high risk dying compared to their counterparts.

5. Conclusions

- Attaining the anticipated 2015 Millennium Development Goal 4 is impossible with the prevailing high under five mortality estimates. This paper delved into exploring the effect of household characteristics on child survival status. Findings show wide mortality differentials by household type, place of residence, and household size. Mother’s education and children ever born were the two major variables highly associated with child mortality.Basing on the findings, it is imperative that the government together with other development partners, including policy makers, programme managers to design programs that will directly sensitize people on the danger of having so many children born in the households. There is need for the government to encourage mothers’ secondary and above education. Massive public awareness should be made to educate people on the dangers of bearing children beyond the age of 40 years and its consequences on children. People should also be sensitized and encouraged to have few people in the households. The government should further elevate mothers economically so that they can provide the basic requirements for the children.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors wish to thank the Uganda Ministry of Health for availing the data set used in preparing this paper.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML