-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Sociological Research

p-ISSN: 2166-5443 e-ISSN: 2166-5451

2012; 2(1): 1-10

doi:10.5923/j.sociology.20120201.01

Habitual Lying Re-Examined

Kristijan Krkač1, Damir Mladić2, Stipe Buzar2

1Department of Marketing, Zagreb School of Economics and Management, Zagreb, 10000, Croatia

2Dubrovnik School of Diplomacy, DIU International University, Dubrovnik, 20000, Croatia

Correspondence to: Stipe Buzar, Dubrovnik School of Diplomacy, DIU International University, Dubrovnik, 20000, Croatia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In this paper, the authors discuss the phenomenon of habitual (or automatic) lying and compare it to the standard criterion of lying. First, two cases are presented. Habitual lying seems to occupy the middle ground between telling the whole truth and telling a lie with previous intent to deceive. Finally, the authors try to answer some of the most probable objections to such a criterion of habitual lying – that the criterion itself rests on the basic distinction between an intent to deceive prior to the act of uttering a false sentence as being true (or vice versa) and an intention implicit in the very act of uttering a sentence. In the conclusion of the paper, the authors offer some practical consequences and groundings, particularly for the case of corporate social irresponsibility.

Keywords: Ferengi, habitual lying, House MD, intent to deceive, intention implicit in an act, intention previous to an act, lying, lying automatically, Searle, truth-telling, Wittgenstein

Cite this paper: Kristijan Krkač, Damir Mladić, Stipe Buzar, Habitual Lying Re-Examined, American Journal of Sociological Research, Vol. 2 No. 1, 2012, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20120201.01.

Article Outline

- “Nothing means anything. Everything’s permitted. Nothing is forbidden. So, anything goes.” No means no, “Mondo Nihilssmo”, “All Roads Lead to Ausfahrt” (2006)

1. Two Short Cases

- Instead of a standard introduction, let’s examine two brief cases introducing us into a worldview of lying. Both cases serve to describe a world in which lying is a standard procedure and is performed automatically. However, the automatism of lying doesn’t prevent the protagonists from understanding and rationally explaining “what” they are doing and justify “why” they are doing it.

1.1. Ferengi

- What is a Ferengi? It is a (funny) humaniod alien race known to us from the Star Trek franchise.1 What distinguishes them from other races? Well, their race and entire civilisation is based on radical laissez faire liberal economic principles with a corruptive and bribery-apt twist. Episodes of Star Trek dealing with the Ferengi emphasize subjects such as trade, profit, Rules of Acquisition2 (RoA), ear-size(“A wise man can hear profit in the wind”) etc. The acquisition at hand is a process consisting of the following five stages: (1) infatuation: an intelligible love or attraction; (2) justification: a moral excuse used to explain the infatuation; (3) appropriation: taking the desired object for one’s self and excluding all others; (4) obsession: a compulsive or irrational preoccupation; and (5) resale: the action of selling the object previously bought.The Rules themselves need not necessarily be conceived as rules but rather as a set of guidelines that lead a Ferengi to his wealth. Still, breaking some of them is often a culpable deed. Some of these rules are the following (Behr 1995):“When in doubt, lie.” (Rule 266) “Keep your lies consistent.” (Rule 60) “Don't lie too soon after a promotion.” (Rule 19) “If you can't break a contract, bend it.” (Rule 5) “You can't cheat an honest customer, but it never hurts to try.” (Rule 2) “There’s nothing more dangerous than an honest businessman.” (Rule 27)The rules mentioned here can be divided in two groups. The first three rules concern lying directly, advising a Ferengi to lie, but to go about it in a consistent and intelligent manner. The third rule advises not to lie in order not to be disclosed in lying. The following three rules are more complicated since they mention lying alongside other forms of deceit. Rule 284, however, opens an important issue. The rule says “Deep down everyone's a Ferengi.” It is of such importance because it reveals that Ferengi know what they are and that they follow their rules rationally and consciously.

1.2. House MD

- Now, imagine a medical doctor who solves 99% of all his cases. These are quite complicated and unsolvable by at least 50% of all MDs. Of course, in the present state of medical expertise and knowledge such an MD is impossible simply because it is physically impossible to know enough about each and every field of medicine. What is important for this paper is that even in such an imagined case, a doctor is forced to lie all/most of the time in order for his character to be minimally consistent. The example of such a doctor here presented is House MD, a character in the TV series with the same title. Our next question is thereby: How and to whom does he lie? He lies constantly, to different people, namely patients, co-workers, his boss (Ehrenberg 2009:180-1), his friends (Waller 2009:209-13), and various strangers. He lies concerning a variety of topics like his profession, his expertise, his physical, intellectual and mental states, day to day trifles etc. But more interesting than the select group of people he lies to, is the issue of method – how he lies. Here we can summarize in the following manner: though he sometimes lies with previous intent to deceive, most of the time he lies automatically. The last approximation can be justified by results of research by experts, namely by referring to the book “House and Philosophy, Everybody Lies” edited by Henry Jacoby (Jacoby 2009). “Though House cares about finding the truth, he does not care about telling the truth. He lies to Tritter, and he lies to his colleagues about being off Vicodin. He also deceives other doctors.” (Battaly, Coplan 2009:226) What is important isn’t just the fact that he lies to most of the people most of the time -- that he lies automatically -- but first and foremost that he has a “theory” which says that “everybody lies”. As said, it can be assumed that this “theory” is necessary for character consistency, yet it is interesting that he thinks of it and that he plainly and clearly spells it out. The “theory” is obvious and explicitly stated by House. “Patient: He’s your friend huh? Wilson: Yeah. Patient: Does he care about you? Wilson: I think so. Patient: You don’t know? Wilson: As Dr. House likes to say, everybody lies.” (Waller 2009:209) The following list of citations can make one familiar with House’s “theory” and practice. “The kind of moral luck involved here is called resultant luck. We can mitigate resultant luck somewhat by attempting to control for as many factors as we can — much as House controls for the probability of his patients’ being deceitful by holding “Everybody lies” as a firm rule — but ultimately much is beyond our control.” (Dryden 2009:42) “House constantly insists that “everybody lies.” (In season three he goes so far as to say, “Even fetuses lie.”) House is consistent in this attitude regardless of whether the lies are due to genuine dishonesty, lack of self - knowledge, embarrassment, or ignorance.” (Ruff, Barris 2009:85)Everybody lies is explicated here as a “solid rule”, yet the question that interests us is the question of it being a routine practice. An affirmative answer to this question is supplied by the following quotes:“Compared to House, patients are a very ignorant bunch. Compared to Tritter, people are a very powerless bunch and are; furthermore, ignorant of what is in their own best interest when they run afoul of the law. This is highlighted by House and Tritter’s shared refrain: “Everybody lies.” People lie to both kinds of authority because they are ignorant. People usually lie when they think they are protecting their interests by doing so.” (Ehrenberg 2009:180) “House routinely tells others exactly what he’s thinking and what he’s feeling. Of course, conventional morality tells us to be polite, but being polite isn’t always honest. And truth is critical to House, who comments on the hypocrisy and dishonesty of his patients and others with his refrain “Everybody lies.”” (Fitzpatrick 2009:190)As far as we know this was the second time in a film or TV series history that a character or a whole humanoid species had a theory and a practice of automatic lying in addition to their explicitly stated theory about it. The first case was of the humanoid species Ferengi. They have their “Rules of Acquisition” that explicitly order them to lie and they follow these rules strictly. The second case was of doctor House who has his rule “Everybody lies”. Both cases can serve as thought experiments which can be useful if one wants to describe how we “real” or “ordinary” humans do precisely that in our “ordinary” lives though we never talk about it in the above described ways. That is the issue of the present paper.

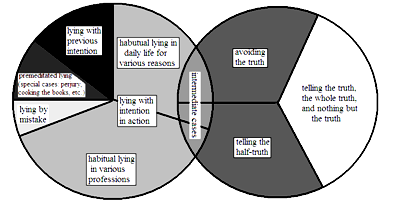

2. The Problem of Intermediate Cases between Telling a Lie and Telling the Truth

- Lying has been the issue in ethical inquiries throughout history, as well as among contemporary philosophers (See Siegler 1966:128-136, Mannison 1969:132-144, Chisholm, Feehan 1977:143-159, and Adler 1997:435-45). With minor differences, most of them agree that lying is uttering a false sentence as being true (or vice versa) with a previous intention to deceive and, as such, it is quite distinguishable from telling the truth. On the other hand, “to lie” is a speech act like any other and it should be performed properly (satisfied, happy, etc. similar as “to pretend”, Austin 1961:201-20), and “lying is a language-game that needs to be learned like any other one” (it should be learned and practiced properly, Wittgenstein 2001 §:249). “Being truthful” and “being dishonest” are practically irrelevant for understanding lying. What seems to be much more interesting are cases where these two are hard to distinguish because there are lies which do not include previous intent to deceive, and there are truths which are in fact half-truths, incomplete truths, or avoidances of the truth. 3So, back to some examples. (a) Say that a mother with her son is crossing the street where a horrible car accident has taken place, and if a child asks “What’s going on Mom? Why is that man lying in the street all covered with red paint?” Then, if the mother says “Oh Willard that is nothing; they are just making a movie”, she is lying and she does it without any previous intent to deceive her son Willard. To the contrary, her lying is a part of a completely different intention, that is to say the overall intention or spirit of protecting Willard from perceived potential harm.(b) Say that in an advertisement for a quite popular soft drink an actor says “… and it is sugar-free too!” Now, the analysis of this particular soft drink shows that it has sugar, but contains no “added sugar” (which can cause some serious health problems for certain consumers). This case, like many others in the advertising industry, is not considered to be a case of lying. However, it does contain something between telling the half-truth and avoiding the truth about the product's characteristics.(c) Say that Norman asks Ludwig “What’s the time?” and if Ludwig answers “I don’t know” while having a watch which is working properly and telling time correctly. Here Ludwig is not telling a half-truth, but lying. However, if Ludwig has some kind of idiosyncrasy, a private policy to answer to this particular and a series of similar questions (e.g. “Excuse me, do you know where this street is?”) by saying “I don’t know”, then there is no intention previous to an act of uttering “I don’t know”. On the other hand, Ludwig can say “But I really didn’t know, since I haven’t taken a look at my watch for quite some time.” This case can then be about avoiding the truth as well as lying without a previous intent to deceive. (d) Two CEO's are chatting at some gala event for the best companies of the year. One asks another, “Say Rudolph, at my company the workload is 40 hours per week. How much is it in yours?”, and Rudolph instantly answers, “40 hours as well.” Now, Alfred was talking about “standard work week” which is commonly implied. On the other hand, Rudolph, while knowing exactly what Alfred was asking, answered in terms of “average work week” which is by coincidence 40 hours too. The fact is that in Rudolph’s company there is no standard work week at all. Here, there was no previous intention to deceive, at least not previous to the very act of uttering “40 hours as well.”, yet Alfred was deceived. On the other hand, Rudolph answered the question literally, that is without taking into account commonly implied meaning of the expression “work week” meaning “standard work week”. This case is obviously an intermediate case between lying without previous intent to deceive and telling half-truth (if the supplied information can be counted as half-truth at all).The case (a) is obviously a case of lying without previous intent to deceive, the case (b) is obviously something between avoiding the truth and telling half-truth, cases (c) and (d) are cases which could be a kind of blend of lying without the previous intent to deceive and avoiding truth (c), or telling a half-truth (d). Now, the standard and common criterion is setting only a radical case as it were the border of lying but only on one side while leaving border porous on the other, much more interesting side. In order to understand this side of lying we need to investigate this leaky side or intermediate cases (as shown in Figure 1).

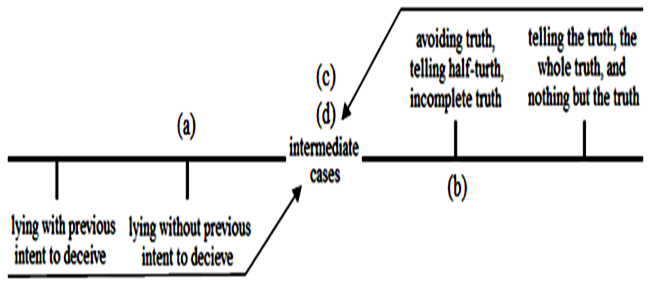

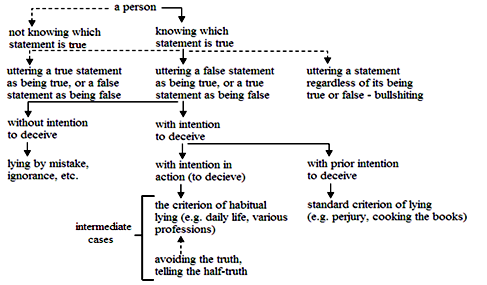

3. The Standard Analysis of Lying

- The standard criterion of lying says that in any situation whatsoever in which β asks α to tell him/her is P true regarding R, α is lying to β iff: (1) P is false (for instance), (2) β does not know is P true or false, (3) α knows that P is false (1), (4) α knows that β does not know is P true or false (2), (5) α knows what is true regarding R, namely, that Q is true, (6) α has intent to deceive β previous to the very act of uttering P, and (7) α utters P.This criterion (1–7) can be branded as the criterion of lying with prior intent to deceive. This criterion is appropriate for a number of simple daily cases like lying to those who would not understand the truth for any reason (because they are too sensitive and would probably do something hastily, because they are children, because they are mentally challenged persons, and similar), to those who “cannot handle the truth”, and suitable for a number of somewhat more complicated cases like false swearing, perjury (Clapp 1996), or creative accounting, cooking the books (Loomis 2001, see Figure 2).Furthermore, the criterion is quite clear. It consists of three groups of conditions. Namely, condition (1) can be regarded as the truth-condition; conditions from (2) to (5) can be considered as knowledge-conditions; condition (6) can be regarded as the intention-condition; while condition (7) can be understood as the action-condition. Regarding condition (1) there is some difference in the type of questions and answers, that is to say, the questions can be regarding some P being true or false (“Is the answer c true or false”), regarding a state of affairs (“Is it already four o’clock?”), regarding the opinion of a person (“What do you think of him?”) and similar. Now, these conditions seem to be necessary if taken individually, while taken together they are sufficient for lying. This point needs a more detailed explication. If one is asked a simple question in order to lie, one needs to utter a false sentence as being true (or vice versa), since if one utters a true sentence, than one is not lying but telling the truth. That concerns condition (1). Condition (2) is obvious too, because the one to whom another lies needs to seek knowledge genuinely, since if this is not the fact, than the liar cannot be sure if the other one trying to expose her/him as a liar (this point is important in view of the success of lying). Conditions (3) and (4) are also necessary in terms of knowledge or strong belief. Condition (5) seems to be unnecessary. If one of these elements is missing then we have an intermediate case between lying and bullshiting (Frankfurt 2005, see Figure 3). Condition (6) seems to be quite important since one needs to have some kind of previous intention to deceive another person by uttering a false statement as being true. This condition is obviously necessary; however it is not sufficient if conditions (1-5) are not satisfied. Finally, condition (7) is necessary because if there is no utterance, than there is no lying stricto sensu (there are some language- games in which silence can be regarded as some kind of “saying something” but such exceptions are beside the scope of this analysis). In the end, this criterion seems to be very strict and according to it, none of us lie very often, In fact, it seems quite demanding to lie properly. On the other hand, we are sure that we lie much more than this criterion tolerates. In short, this criterion is too rigorous. The question is – is it perhaps the special case of some more broad-spectrum criterion?

3.1. A Short Literature Review Concerning New Analyses of Lying

- Thomas L. Carson, in his book “Lying and Deception Theory and Practice” (Carson 2010, Sorensen 2007, Fallis 2009), supplies an argument in favor of lying without an intent to deceive (Carson 2010:20-3, see also Carson 2006, 2008). Surely his argument and examples make sense, yet it has nothing to do with the type of lying that is examined here, namely, lying with intent to deceive but with an intention-implicit-in-action. Carson’s idea is that there are cases in which one makes a false statement and the deception one produces by making such statement is “merely an unintended side effect” (Carson 2010:20). On the other hand, if “to say something false without an intent to deceive” is really possible, then it makes sense to ask if there is any relevant difference between “stating a false statement for some reason and solely by doing that deceiving others” and “stating a false statement without an intent to deceive and solely by doing that deceiving others”? Namely, if S has a reason for stating a false statement, then this is surely different from S’s intending to deceive B by stating a false statement. Reasons and intentions differ. However, if B is ipso facto deceived by S’s stating a false statement for some reason and without previous intent to deceive anyone, then such deceit could be a deceit only if intended. Yet, S didn’t intend to deceive previously to uttering a false statement, and, say that B was really deceived. If there must be an intent to deceive, then it is surely anintent to deceive by the very act of uttering a false statement, with or without any reason. In all Carson’s examples persons are intending something else but not to deceive. For instance in the case of a student’s bald-faced lie (a barefaced or bald-faced lie is one that is obviously a lie to those hearing it): “He intends to avoid punishment by doing this. He may have no intention of deceiving the Dean that he did not cheat.” (Carson 2010:21). These two intentions differ. Nevertheless, there seems to be the problem here.● S intends to avoid punishment. S utters a false statement to B. B hears a false statement made by S. B is deceived. S didn’t have intent to deceive B. S deceived B. B surely isn’t unintentionally deceived. B was intentionally deceived.Whose and which intention was it? Sissela Bok claims that a lie is a statement intended to deceive a dupe about the state of the world, including the intentions and attitudes of the liar. (1978:13) Is it possible then that there are cases in which by intending one thing, which is different from intent to deceive, previous to an act of uttering a false statement implies that by the very act of uttering false statement one “produces” intent to deceive and deceives other person as a necessary side effect? If this is possible, then S didn’t intend to deceive B previous to an act of uttering a false statement, but by the very act of uttering a false statement to B S produced and manifested intent to deceive.

| Figure 1. Intermediate cases between lying and truth telling |

4. The Criterion of Habitual Lying

- There is something dodgy concerning the previously mentioned criterion of lying, and it can be described in terms of the following criterion. (1) P is false (there are other possibilities here), (2) β does not know is P true or false, (3) α knows (1), (4) α knows (2), (5) α knows what is true regarding R, namely, that Q is true, (6) α utters P.The listed conditions are identical to those in previous section except for condition (6). This second criterion is more wide-ranging, and the first one seems to be its special case. In addition, this criterion still leaves enough room for half-truths which are not lies, but also not “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth”. The question concerning these conditions is simple. Which act is one performing, if not lying, if one satisfies these conditions? Since there are no other candidates, and since one surely performs an act by uttering P, the only solution is that one is lying, and this criterion as “the standard criterion minus previous intention” we brand as “habitual lying” (concerning the initial idea explicated in 2007 by Krkač and Lukin, see D'Anselmi 2011:47-8).

5. Some Objections and Responses

- Here we will now list some objections to the second criterion and supply some possible responses. One can say that one uttered P by mistake, as lapsus linguae for instance. In such cases one will surely correct himself as soon as the mistake is noted. There is of course the small possibility that a person will not do that because, for example, he is too embarrassed to admit that he made a mistake and (fortunately) he is the only one that actually noticed the mistake. For the purposes of this article we can rule out this and similar exceptions. Say that these exceptions are ruled out. Conversely, this is noteworthy since if one utters a false statement believing it to be true, then one is, as T. Aquinas says, “lying only materially, but not formally”, because “falseness is beside the intention of the speaker.” (Aquinas 1947, ST, II-II, Q.110, a.1) This can be labeled as a kind of lying by mistake, or lying without previous intention. Another objection is that one has to have a previous intention to deceive in order to lie. Now, this is not precisely the case. If we humans talk by default and if lying is a language-game as any other, then in most cases we also lie by default, automatically, or habitually (in all cases in which we consider lying to be allowed, tolerable, and necessary). If we do so, then there is no need for intent to deceive previous to the act of uttering a false sentence as being true. However, some kind of intention is surely needed. Here, one can distinguish between: (6.1) explicit intention to deceive clearly present in persons mind prior to an act of uttering P, (6.2) and intention to deceive implicit in act of uttering P and undoubtedly manifested by it. J. R. Searle’s idea regarding this distinction can be helpful. “A common mistake in the theory of action is to suppose that all intentional actions are the result of some sort of deliberation […] but obviously, many things we do are not like that. We simply do something without any prior reflection. For example, in a normal conversation one doesn’t reflect on what one is going to say next, one just says it. In such cases, there is indeed an intention, but it is not intention formed prior to the performance of an action. It is what I call intention in action.” (Searle 1984:65, italics are added) If this is correct, then intention can be implicit in an act of uttering a false statement as being true and manifested by it (6.1 is simple explication of the condition 6, and 6.2 of the condition 7). This point goes along nicely with the rhetorical question asked by L. Wittgenstein: “To what extent am I aware of lying while I am telling a lie?” (Wittgenstein 2004 §§:189-90) Most of the time we are not aware of this so called intention in action, but there is an intention no matter if it is implicit in action. Here, one can distinguish between having an intention in terms of manifesting it and being conscious of intention. On the other hand, habitual lying as described has many similarities with avoidance of the truth and with telling the half-truth (as shown in Figure 2).

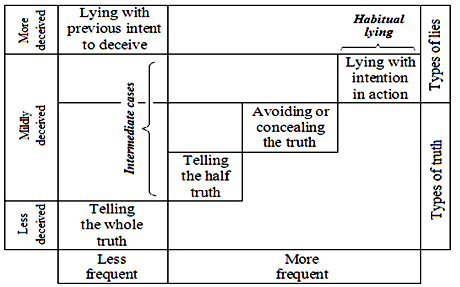

6. Concluding Remarks

6.1. Theory

- Nonetheless, we humans override H. G. Frankfurt’s explanation, namely, the fact that a statement quite often is false and that summarizes another consequence, i.e., that we lie much more than we in fact believe we do. This overriding, i.e. rationalization, is a part of the good practice of various professions like the legal, business, political, medical and other professions, as well as a part of our daily life where such habitual lying, is a part of upbringing, customs, and culture. We can make a kind of approximation vis-à-vis the frequency of lying regarding mentioned types, and a propos being more or less deceived by a particular type of lie (as shown in Figure 4).

| Figure 3. The pattern of lying |

| Figure 4. Types of truth and types of lies concerning their frequency (an approximation) and level of misinformation (less, mildly, more) |

6.2. Practice

- Now, concerning some strange cases of habitual lying, the following should be suggested. Habitual lying is a part of our daily lives. Its frequency is beside the point here. What is important here is that we habitually lie: to ourselves (self-deceptions, rationalizations, and similar) to each other: privately to our spouses, children, friends, neighbors, and similarly, publicly to our clients (legal professions), bosses (business), patients (medical professions), etc. And for that matter in business too (Loomis 2001): to our co-workers, owners, bosses, co-workers (as internal stakeholders), to our customers, buyers, to the media, to the local community, to various state agencies (as external stakeholders of a company, though this point will be explicated in the next section).Here, there is no need for special evidence on the very nature or frequency of habitual lying in these spheres, simply because this type of lying is an essential part of human culture, under the implicit premise that a culture exists and is relevant yet different from human nature, and that it is differently actualized and achieved in different societies. It is clear that human cultures would be completely different if they did not include the actions of habitual lying or telling the truth, only the truth, and nothing but the truth to ourselves, our children, spouses, friends, and others. However, habitual lying in these cases should be distinguished from various phenomena that are quite similar to it, such as: lying with previous intent to deceive (discusses here), telling the half-truth, not telling the whole truth, and similar, bullshit (Frankfurt 2005, Debeljak, Krkač, Banks 2011), pretending (Austin 1961), etc. For that matter habitual lying is much closer to bullshit, pretending, deceiving, telling the half-truth and similar, than it is to lying with a previous intent to deceive. Perhaps the name “habitual lying” itself is a bit misleading since it is practically closer to these other phenomena. However, it is conceptually and theoretically closer to the phenomenon of lying. However, if any case of habitual lying produces the same or similar damage as pure lying, then pragmatically speaking there is no relevant difference, at least from some consequentialist ethics points of view like New Testament ethics, utilitarian, pragmatist, ethics of responsibility, ethics of communicative action, etc. If this is not the case, then it is possible to claim that habitual lying is a kind of cultural practice which is standard, custom, and routine in our daily lives, private and public, and by which in all situations where there is no other choice, we produce less damage then by telling the truth.

7. An Application: Corporate Social Irresponsibility - CSI

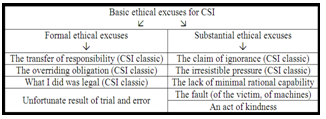

- Excluding fictional doctors and humanoid species from sci-fi series (see here 1.1. – 1.2.) one can wonder – if there is a habitual lying phenomenon as a standard procedure in some spheres of society or among members of any particular social strata. Contrary to our first impression, this has nothing to do with our experiences that point to lawyers/solicitors, politicians, various officials, and medical doctors as professionals whose work includes a kind of habitual lying. In other words, this question cannot be answered in general. Rather, a case or two can be supplied. The case of lying in business, which will be described in what follows, is a part of the overall issue of human irresponsibility. Therefore, a kind of fusion of bottom-up (a case study) and top-down (from principles to practices) perspectives is needed in order for one to “see” the pattern of the phenomenon of irresponsibility. Humans seem to be neither irresponsible nor responsible by nature. As any other species they are also subject to acquiring and learning particular ways of speaking and acting (speech acts, language-games and forms of life), or of lying. It is reasonable to claim that humans generally try to nurture their young in such a way that they act responsibly in future situations. However, even if they do succeed, we humans, from time to time, act irresponsibly, which means that the tendency to act irresponsibly is a part of a general conditio humana. In most cases humans are irresponsible due to various omissions, mistakes, lack of knowledge, unsuitable motivating factors, stubbornness, etc. Nevertheless, it seems that there’s more to it. Surely there are some contexts that make human irresponsibility more frequent, a long-term practice, and almost systematic. Sometimes it turns out to be a part of human habit; as there was a certain culture of irresponsibility. The context of individualism seems to be one such context. Within the scope of such cases humans are irresponsible privately and publicly, toward themselves, other individuals (human and non-human), groups, society, and whole generations. If they are a part of companies or corporations they can act irresponsibly in numerous ways, and then they are executing the irresponsible actions of a company as a legal person carrying out activities for profits. Corporate social irresponsibility (CSI) is related to common and extraordinary irresponsibile actions done by corporations. However, there are two, perhaps conflicting, sides of the story about the principle issue of responsibility. One says that nowadays, in the age of radical individualism, it is very hard or even almost impossible to be responsible. The other explanation says that it is irresponsible to believe, claim, and act upon this impossibility, no matter how hard it may be to find out what responsibility really is, toward what or whom do we have it, and how to carry out responsibility in terms of particular duties or obligations in particular circumstances. Therefore, on one hand stands the impossibility of responsibility. Pascal Bruckner in his book “Temptation of innocence” (1995) writes the following: “The temptation of innocence is a sickness of individualism which is founded on the effort to avoid consequences of one’s actions, and attempt to enjoy advantages of freedom without suffering any of its difficulties or troubles. It branches in two directions, infantilism and victimization, two ways of escaping the burdens of Being, two strategies of blessed irresponsibility. In the first case, the innocence should be conceived as a parody of youthful carelessness and ignorance; it reaches its climax in the character of an eternally immature. In the second case, it is a variation of an angelic feature, representing an absence of guilt, incapability to perform evil, and it is incorporated in the character of self-proclaimed martyr.” (Bruckner 1995:12) On the other hand, there is a demand for responsibility (Jonas 1984). To proclaim and to defend a kind of “ethics of responsibility” in the presented cultural context, seems to be at least a naïve thing to do, since there are no responsibilities, and no one is responsible before and for no one else. This stands for all aspects of responsibility. These are: descriptive, in terms of the relation between a doer, an action, and the consequences of an action; normative, in terms of stating a moral duty or obligation for something or someone while performing an act, and prescriptive, in terms of an imperative (a duty, a command, or an order) fora certain obligation toward something or someone. In short, one cannot be individualist and a responsible person in the same time without ending in some serious perplexity which manifests itself as a contradiction or a paradox on the conceptual level, a rationalization on the psychological level (in terms of solving a cognitive dissonance), and finally as a nice private idiosyncrasy (or as a private irony on a cultural level, Rorty 1989). In business, CSI comes in almost all spheres (business sectors as well as business aspects i.e. management, marketing, finance, accounting, etc.) concerning core businesses, core competencies, standard operating procedures, job descriptions, professionalism, etc. and the demand for CSR comes only in terms of ethical codes which are closely related to professionalism because for a professional to perform a job professionally is the basic duty. Therefore, in its rudimentary form, a CSI activity can be described as an intentional violation of a core business, standard procedures, professionalism, explicit code of ethics, and CSR procedures by private legal persons carrying out publically activities for profit. There are various kinds of CSI, e.g. partial, overall, amateur, professional, typical, extraordinary, tactical, strategic, etc. However, excuses for CSI are similar to justifications of irresponsibility made by individual physical persons (see McDowell 2000, as shown in Figure 5).

| Figure 5. Groups of ethical excuses |

NOTES and ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Some parts of last section are based on a working paper by K. Krkač (2011) “Corporate Social Irresponsibility, A Conceptual Framework”, in Social Responsibility Review, 2011, No. 3, pp. 78-89, ISSN: 1759-5886, URL: http:// www. socialresponsibility.biz/2011-3.pdf. This text as a part of different lectures was delivered on various occasions: at Annual Symposium of Philosophical Faculty at University of Rijeka, Croatia, 2007 (Krkač); during the undergraduate course Introduction to business ethics and CSR at Zagreb School of Economics and Management, Croatia, 2008/09, 2010/11, and 2011/12 (Buzar, Krkač), as a part of the course An introduction to ethics and CSR at Institut D'etudes Politique de Lille, University of Lille 2, France, 2010/11 (Krkač), and as a part of lecture during “Philosophical Marathon” at Faculty of philosophy, University of Ljubljana, 2011 (Krkač).We wish to thank Paolo D'Anselmi, Jelena Debeljak, Borna Jalšenjak, Josip Lukin, Duncan Richter, Neven Sesardić, Peter Singer, Ivan Spajić, and Matej Sušnik for valuable comments and suggestions. We especially wish to thank Janice McCormick for her review of the paper. We also like to thank all participants in discussions for various objections and criticism that improved lectures and various drafts of the paper.

Notes

- 1. Although they appear in four of the five official series of the Star Trek franchise, they are best represented in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-1999) and any reference to them in this paper may be directly associated to that particular series.2. A manuscript containing rules and guidelines that Ferengi must and/or should (depending on the specific rule) conduct themselves by whilst doing business. It was written by the half-mytical founder of their society, Grand Nagus (his title) Gint. 3. Before we actually start by providing examples in order to clarify this allegedly grey area, perhaps a minor note on the approach to the topic in question is needed. This paper is an attempt at the philosophical analysis of lying and as such it is tries to research the field from a more theoretical perspective. There is a large amount of data collected on the phenomena of lying in other disciplines. If readers are interested in different theories please consult for example McCornack (1992), or Buller and Burgoon (1996). These and many others noteworthy readings offer a good view of different approaches to the field, but for the purpose of this paper we shall concentrate on the philosophical, that is to say, conceptual approach (with a little bit of the pragmatic one too).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML