-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Science and Technology

p-ISSN: 2163-2669 e-ISSN: 2163-2677

2024; 14(2): 22-30

doi:10.5923/j.scit.20241402.02

Received: Nov. 3, 2024; Accepted: Nov. 20, 2024; Published: Nov. 22, 2024

Smart Micro-Gasifier Stove: Performance Optimization Using Embedded Systems with IOT Integration

Tina Nkhoma, Daliso Banda

Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, The University of Zambia, School of Engineering, Lusaka, Zambia

Correspondence to: Tina Nkhoma, Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, The University of Zambia, School of Engineering, Lusaka, Zambia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The traditional methods of cooking in many developing countries heavily rely on solid fuels such as wood, charcoal, and agricultural residues, leading to deforestation, indoor air pollution, and adverse health effects. Gasification, a technology that converts solid biomass into clean-burning gas, offers a promising solution to mitigate these challenges. This study explores the ways in which the gasification process can be optimized. It utilizes a mini gasifier stove embedded with two 12V DC fans to control primary and secondary airflow separately. An embedded control system is employed, consisting of sensors that measure ambient temperature and gas concentration, along with a microcontroller that receives input from the sensors and outputs instructions to the fans. Ultimately, this system controls the combustion process by regulating the amount of oxygen supplied. Further, an IOT system was developed and integrated to monitor and display temperature readings, CO gas concentration and fan operating speeds, thus making the gasifier stove a smart device that can communicate over a network. In this study, a Raspberry Pi Pico W was successfully used to control airflow for combustion via the two embedded fans and a simple HTTP web server was configured on it to display the measured data via a static website. By employing different settings of duty cycle for PWM control, it was determined that the optimal ratio of primary to secondary air required to achieve the lowest possible levels of CO emissions in a simple TLUD gasifier stove was 30% to 100%. It was also observed that, with this design, independent control of primary and secondary air allowed for a reduction in primary air supply while maintaining the CO emissions at the lowest possible detectable levels once a stable burn was attained. The primary air could be reduced by a speed of 3,360+/-20 rpm while maintaining the lowest CO concentration of 0.4 ppm, representing only a 2.6% increase from the levels detected by the sensor in ambient air. However, any reduction in secondary air resulted in an increase in CO concentrations.

Keywords: Gasification, Control system, PWM, IOT, TLUD, Raspberry pi Pico W, HTTP Server

Cite this paper: Tina Nkhoma, Daliso Banda, Smart Micro-Gasifier Stove: Performance Optimization Using Embedded Systems with IOT Integration, Science and Technology, Vol. 14 No. 2, 2024, pp. 22-30. doi: 10.5923/j.scit.20241402.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A micro-gasifier stove is a small device that creates its own gas from solid biomass and is small enough to fit directly under a cookpot. Gasification is a chemical process that converts carbonaceous materials like biomass into useful convenient gaseous fuels or chemical feedstock [1]. Biomass is organic, meaning it is made from living organisms i.e., plants and animals. It represents approximately 14% of the world’s energy consumption and can be converted into bioenergy (heat/power), biofuels, and bio-based chemicals and materials through various thermochemical and biological conversion technologies [2]. The utilization of renewable resources to replace fossil fuels has gained widespread attention due to the depleting and polluting nature of fossil fuels. In this context, biomass as a source of renewable energy has derived a special focus as it can be converted into various types of biofuels. Instead of direct burning of woody biomass as an energy source, converting the woody biomass into biofuel makes the full utilization of its potential [3]. There are so many different variations of gasifier stoves, and each can use different types of biomass for fuel. Biomass fuels available for gasification include charcoal, wood and wood waste (branches, twigs, roots, bark, wood shavings, pellets and sawdust) as well as a multitude of agricultural residues (maize cobs, coconut shells, coconut husks, cereal straws, rice husks, etc) [4]. Approximately 3 billion people, most of whom live in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, rely on solid fuels and kerosene for their cooking needs. Exposure to household air pollution from burning these fuels is estimated to account for approximately 3 million premature deaths a year [5]. Cleaner fuels such as liquefied petroleum gas, biogas, electricity, and certain compressed biomass fuels have the potential to alleviate much of this significant health burden but remain underutilized due to several factors including cost and availability [6], [7].‘The principle of Micro-gasification is a relatively young development which was invented in 1985 and the first commercial micro-gasifier was available in 2003. Since 2011, there has been a significant increase in the diversification of gasifier models with new developments coming up virtually every day’ [8]. The principle of gasification works on separating the two processes of gas creation and gas combustion from solid biomass. In the process of gas generation, solid biomass is converted into gases and guided into a combustion zone. Here, it is burnt with oxygen from a secondary air inlet. To achieve exceptionally clean combustion of solid biomass, the inputs of heat and air can be controlled and optimized. Gasifiers are considered clean methods of burning fuel because they produce very little soot and gaseous emissions. However, in gasification where there is a surplus of solid fuel (incomplete combustion) the products of combustion are combustible gases like Carbon monoxide (CO), Hydrogen (H2) and traces of Methane and non-useful products like tar and dust. Thus, the key to gasifier design is to create conditions such that a) biomass is reduced to charcoal and, b) charcoal is converted at suitable temperature to produce CO and H2 [9].Additionally, a major drawback that leads to not achieving clean combustion of biomass in gasifier stoves is the ability to control the amount of oxygen supplied for the process of combustion [10]. Furthermore, fan assisted stoves bring in a challenge of introducing a second source of energy to drive the fan. This may not be readily available in remote locations.

1.1. Motivation

- Approximately 3 billion people around the world, rely on solid fuels (i.e. wood, crop wastes, dung, charcoal) for cooking needs [11]. Traditional cookstoves based on biomass combustion have low efficiency, thus generating social, environmental, and health impacts [12]. Additionally, cleaner fuels like electricity and petroleum gas are not cost effective. This poses a need for cheap, easily accessible and clean energy solutions. This study aims to enhance the performance of conventional single fan gasifier stoves by the integration of embedded systems control and an IOT monitoring system.

1.2. Objectives

- • To investigate the performance issues of a standard gasifier stove with a single fan• Investigate the effects on performance by integrating two separate fans to control air supply. • Design a control system based on sensors and microcontroller to optimize performance.• Integrate an IOT based monitoring system. ‘The internet of things can be described as connecting everyday objects like smart phones, sensors and actuators to the Internet where the devices are intelligently linked together enabling new forms of communication between things and people, and between things themselves’ [13]. This study focuses on optimizing the performance of a gasifier stove using the internet of things and embedded systems.Extensive research has explored the application of IoT systems in smart homes for automation, smart lighting, security systems, and more. Additionally, significant attention has been devoted to optimizing the performance of gasifier stoves through design improvements and fluid dynamics. However, the utilization of digital systems in gasifier stoves remains relatively underexplored, prompting this study to focus on investigating and addressing this gap.

1.3. Literature Review

- Biomass is renewable organic material (containing stored chemical energy) that comes from plants and animals [14]. It can be burned directly for heat or converted to liquid and gaseous fuels through various processes. It can be used for heating and electricity generation and as a transportation fuel. In many developing countries, it is especially used for cooking and heating. More than three billion people use wood, dung, coal and other traditional fuels for cooking inside their homes [15]. Inefficient wood stoves are responsible for indoor air pollution, respiratory related diseases and deaths but also accelerated deforestation due to excessive fuel consumption [16]. Studies have shown that exposures to indoor air pollution contributes to increased risks of cancer [17], premature mortality, and asthma [18]. This fact highlights the need for reducing harmful emissions from biomass to acceptable levels that would not have negative impact.Gasifier stoves are designed based on the principle of gasification to efficiently convert solid biomass fuels into combustible gases, which can then be burned to generate heat for cooking or other purposes. These stoves offer several advantages over traditional open fires, including higher efficiency, reduced emissions, and lower fuel consumption [19]. To understand the process of optimizing the gasifier stove, the research will first delve into the stages of solid biomass combustion, the types of gasifier stoves available and lastly the challenges that have been identified in the process of gasification and gasifier stoves. Only once we understand how biomass combustion works can we apply some principles to optimise its use.

1.3.1. Stages of Solid Biomass Gasification

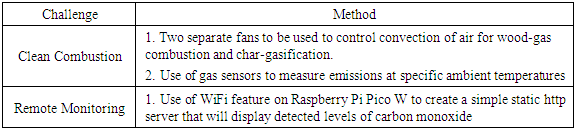

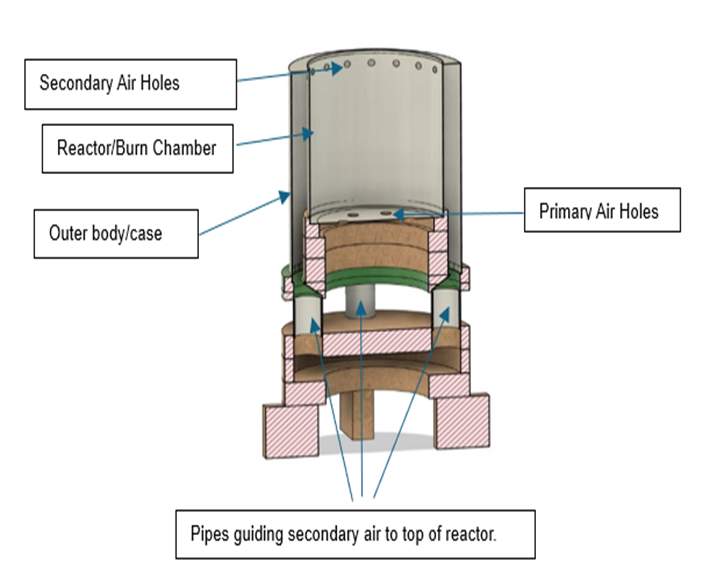

- The process of biomass gasification has four stages, namely, 1) drying, 2) pyrolysis, 3) combustion and 4) char gasification. [20] When we consider the process of gasification, the parameters deemed to affect its performance include; the type of catalyst used, gasifying agents, biomass ratio and temperatures, as well as the type of raw materials [21]. Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of a Top-Lit Up-Draft (TLUD) gasifier stove highlighting the stages of biomas combustion. It also shows where primary and secondary air enter the stove.

| Figure 1. Schematic of TLUD Cookstove |

1.3.2. Types of Gasifiers

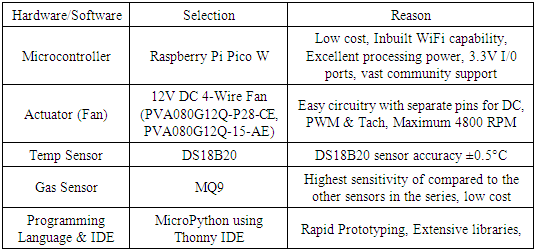

- There are many different designs and types of gasifier stoves that can be distinguished by several factors such as the flow direction of gases (up-draft/down-draft), the gasifying agent (natural air, oxygen, steam) or the methods of creating the draft (natural draft/ fan assisted). Most gasifier stove models follow the basic TLUD principle which stands for Top-Lit, Up-Draft. TLUDs are easy to adapt and replicate within individual projects without patent infringement or copyright issues [31]. The simplest TLUD can be in the form of a single tin can combustion unit with separate entry holes for primary and secondary air.As per figure 2, primary air enters the reactor through the holes at the bottom and moves through the solid biomass fuel. Secondary air enters the combustion zone above the fuel bed. The batch of fuel is fed from and lit at the top and the visible flame is in the combustion zone where secondary air is added above the fuel.

| Figure 2. Schematic of TLUD Cookstove |

1.3.3. IOT and Embedded Systems

- Biomass/gasifier stoves play a crucial role in providing clean cooking solutions, especially in rural areas where access to clean energy sources is limited [35]. Embedded systems and Internet of Things (IoT) technologies offer opportunities to enhance the efficiency, safety, and usability of these stoves. A review of the related works below explores existing research and developments in leveraging embedded systems and IoT in biomass/gasifier stoves, highlighting key findings.

1.3.4. Related Works

- Research by Chaiwong Kanyaporn & Karnjanapiboon Charnyut in 2019 used a bed type gasifier to investigate the temperature by monitoring the gasification process of the stove by using IoT system comprising of a Raspberry Pi 3 model B as a single-board microcomputer that connected to the internet and operated along with Blynk Mobile Application that acts as a system monitoring of the stove temperature in real time [36]. The production and efficiency of the gasification process were considered by controlling of airflow inlet to the stove that optimized for the conversion of biomass to bio-fuel product under the gasification process. The result found that the IoT can be used as a temperature monitoring and air inlet controlling for gasification stove in real time. In this study, only a single air source is being controlled.Another study by Jean Michel Sagouong compared the thermal efficiency of three biomass cookstoves by use of an Ardiuno Mega that was programmed for thermal behavior controlling. This validated data acquisition device set up was provided with type-K thermocouples, LCD Display, SD card module, LM35 and DHT22 sensors. The obtained results of Simple Water Heating Test showed that their thermal efficiencies, charcoal consumptions, time to boil and heat utilized were not far away from others’ in the literature [37].Additionally, a study by J. Shawkat, S.Talukdar, and M. Islam used a Sensor based safety mechanism which could detect the leakage of gas in a gas stove and notify the user through mobile message using an IoT.

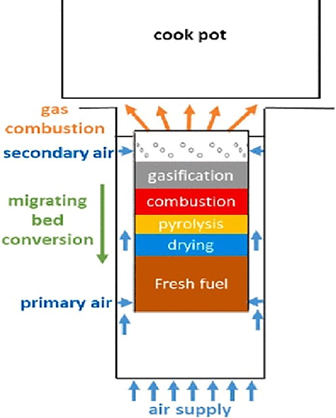

2. Methodology

- The methodology undertaken by this research is experimental and the below sections outline the processes, equipment and electronics used to produce the results. The experiments were conducted in a controlled environment and the ambient temperature was recorded. The experiments were done by alternating the ratio of primary to secondary air flow and recording the amount of CO concentration detected. The readings were displayed on a static website accessible via a website built on a simple http server on the raspberry pi. The wireless feature of the Raspberry Pi Pico W enabled a connection to the home WiFi network.The research experiments utilized a TLUD stove and the table 1 outlines some of the challenges identified and proposed methods of mitigating them.

|

2.1. Gasifier Design

- A simple biomass TLUD (Top Lit Up Daft) stove was designed and built out of steel milk cans using recommended dimensions from literature. The recommended dimensions obtained from literature were the ratios of primary to secondary air holes, the diameter of the holes and the height of the biomass stove itself. The recommended 1:3 ratio of primary to secondary holes was used as it has been proved to give the best efficiency.Therefore, the number of primary to secondary holes was matched to this ratio and evenly distributed across the surface area of the tin can in order to maintain a consistent velocity or air in each target region.Whereas primary air enters the fan using the holes at the bottom of the inner chamber, the secondary air that comes from the bottom fan uses the 4 PVC pipes that are mounted along the sides and lead up to the secondary holes along the edges of the top of the inner chamber. Figures 3 and 4 show the prototype as well as the cross sectional view.

| Figure 3. Prototype micro-gasifier |

| Figure 4. Gasifier stove cross-sectional view |

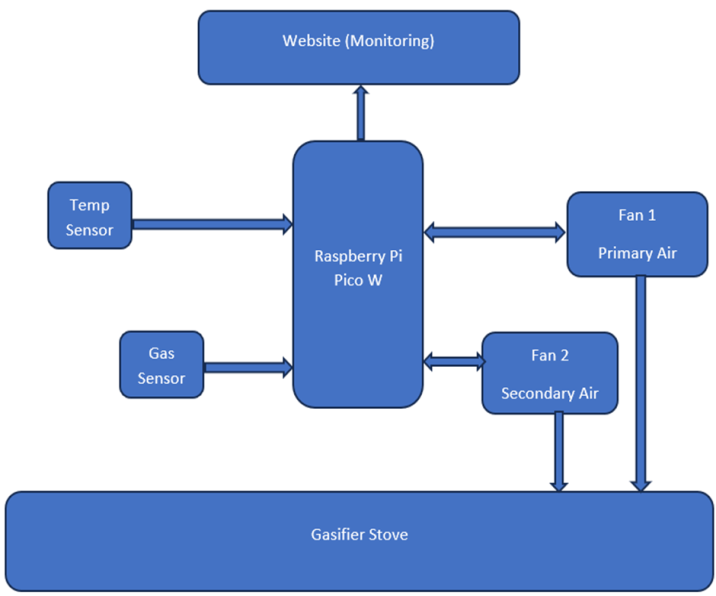

2.2. System Block Diagram

- The entire test bed comprises of the gasifier stove fitted with 2 fans, Raspberry Pi Pico W microcontroller and sensors was assembled, and the electronic circuit was comprised of the easily accessible electronics.The fans are attached to the stove and are outputting the gasifier agent (air) according to the ratios set by the controller. They are directly connected to the raspberry pi Pico and communicate to it bidirectionally by sending tach signals and receiving PWM signals. This is shown in figure 5. The website has a small server that is running on the Raspberry Pi Pico W microcontroller and outputs chosen values of CO concentration, temperature, and fan speed.

| Figure 5. System Block Diagram |

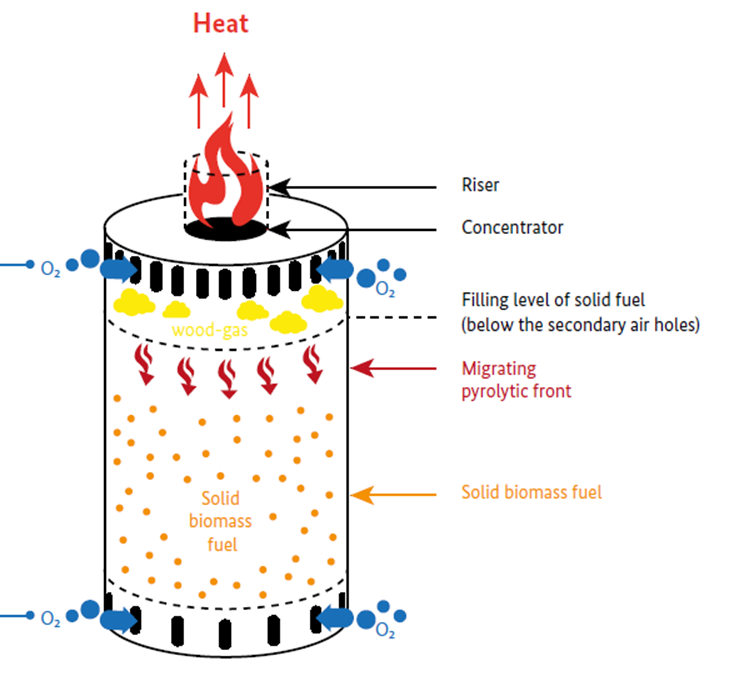

2.3. Equipment Used (Hardware/Software)

- Table 2 summarizes the components of the IoT Ecosystem and illustrates the choice of devices used for this study and why they were selected, based on the literature reviewed.

|

3. Findings and Discussion

- A sequence of tests followed by varying the ratio of primary to secondary air and measuring the amount of CO concentration detected. The results recorded below were obtained in a single run, however, similar behavior was observed in multiple separate runs.

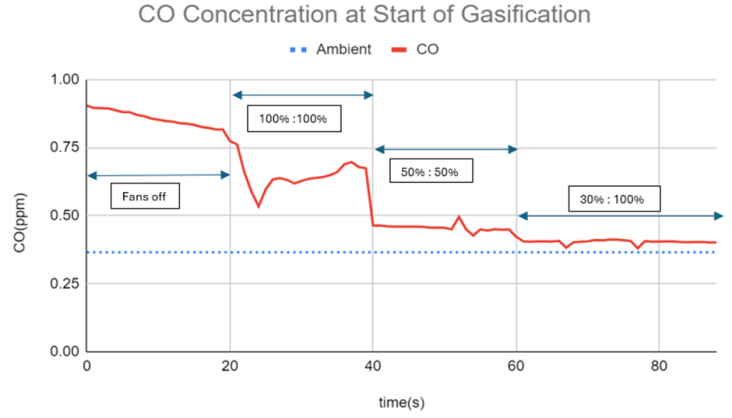

3.1. Results at Start of Gasification

- Before the stove was switched on, the CO output was a constant average of 0.37ppm which was set as the control value. As can be seen in figure 6, the blue trace, which is the CO concentration at ambient condition, represents this fact.

| Figure 6. CO Concentration at start of gasification |

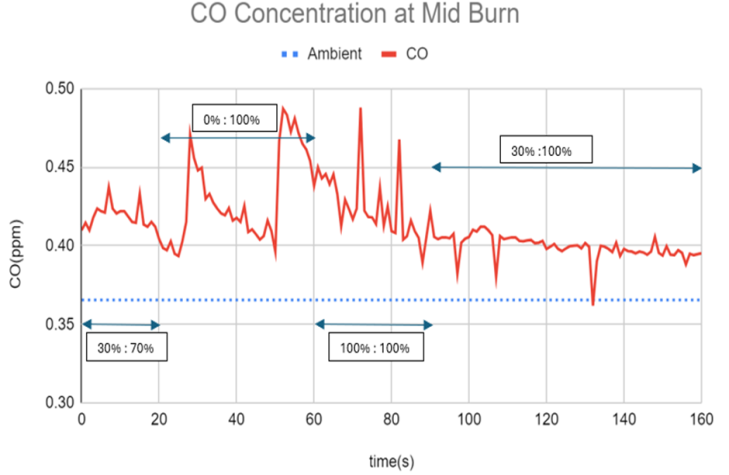

3.2. Results after Steady Burn is Achieved

- Figure 7 shows the results obtained at mid burn, which is a stage when a steady flame has been established across the surface of the fuel bed and the entire surface of biomass fuel has started to further burn into red-hot char. At this point, it is observed that any reduction in secondary air produced either a hike in CO output or fluctuating readings or both. Reducing the amount of secondary air was also observed to produce quite a number of solid particle emissions. More secondary air is gradually required because the amount of wood-gas produced from pyrolysis increases with increase in temperatures. The gaseous mixture is further increased when syngas produced from char reduction adds to the mixture of gases requiring more oxidizing agent. Reducing the amount of secondary air then causes more CO to escape due to incomplete combustion.

| Figure 7. CO Concentration mid-burn |

3.3. Remote Monitoring

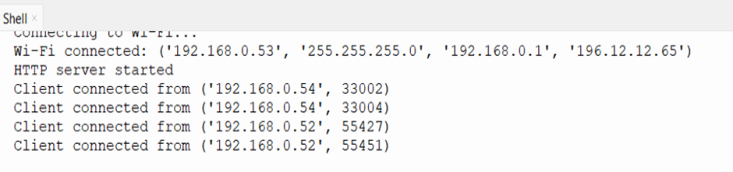

- The Raspberry Pi Pico W was then connected to a home WiFi network and a simple http server built on it. The web server was configured using micro python libraries and it was able to print out values of temperature, Fan RPM and CO concentrations as below.

| Figure 8. Open socket connection from client (website) |

4. Conclusions

- The gasifier proved to be a device that can burn biomass with significantly low levels of emissions compared with open fires. From the experiments done, it is seen that natural air alone is not enough to provide enough oxygen for combustion of gasses. This makes the process extremely smokey and hazardous to health. With the use of two fans to separately control primary and secondary air, almost undetectable levels of CO concentrations are observed at less than 2.6% variation from CO levels in ambient air. The use of two fans makes it possible to reduce the primary air by 70% whilst maintaining the CO emissions at lowest point and maintaining a strong fire intensity. From the experiments conducted, it is seen that the initial unstable stages of combustion can be successfully started with secondary air at half the maximum supply of the fan and primary air at maximum and then gradually adjusted to 30% primary and maximum secondary once stable burn in achieved. Therefore, the study was able to successfully investigate the impact of incorporating two fans for separate control of air flow.Further, the study was able to successfully use a simple control system comprising of a micro controller circuit with micropython programming language to adjust the PWM signal duty cycle to different settings in order to determine the optimal air ratio. The power requirements for the entire system include a single 12V, 1.5A DC supply to power the 2 fans at maximum power of 8W each. This can be provided by a small car battery or portable rechargeable batteries, making it accessible to households in remote areas that do not readily have electricity. The other electronics draw power from the microcontroller's 3.3V output. The controller, requiring between 1.9V to 5V DC, can be powered by a set of AA or AAA batteries.It was further observed that at a higher ambient air temperature of 38°C, a stable burn was able to be achieved quicker than when tested at 24°C. This is because the incoming air does not cool down the hot gases produced from pyrolysis and char gasification as it enters the stove. At higher temperatures, gasification reactions produce more H2 gas than CO which can be beneficial because H2 can be used in further oxidation reactions with CO, thereby reducing unwanted emissions. Additionally, more tar is produced as a byproduct of gasification when temperatures are lower, which dilutes the quality of the syngas.In order to ensure the stove is working at optimal efficiency, remote monitoring via a simple website built on a microcontroller was able to successfully display readings of CO concentrations, ambient temperatures and fan speeds. The user may then be able to adjust airflow to enhance combustion or use the CO readings to tell when the stove is smoking or when the fire has gone out. The website range is just within the LAN, which is the vicinity of the user. With the development of IOT in smart kitchens and smart homes, it gives the device the possibility to communicate with other devices in the home thus contributes to creating an intelligent ecosystem.

4.1. Recommendations

- Gasifier stoves are an advancement to households that rely on open fires for cooking. However, with the current deficit in electricity, they are a good alternative to charcoal which is quite expensive and bad for the environment in that it promotes vast deforestation. There are, however, several functionality constraints that offer room for improvement. One such challenge is the inability to tell fuel levels during the cooking process. Further studies may explore the possibility of using load cells and calibrating them to measure the weight of the stove with and without an added load (cookpot). This study proposes utilizing CO concentration to determine the presence of a flame by comparing detected levels. Further research could investigate using sensors for flame detection. Additionally, further studies may look at using several gas sensors to measure not only CO emissions but Methane, Ethane and other combustible gases.The integration of embedded systems control to the device opens the possibilities of including closed loop control that uses threshold values of either CO concentrations or equivalence ratio (ER) to adjust the air flow automatically.Future work could delve into flame control. This could look at adjusting the intensity of the flame/heat in three stages of full blast, middle and low heat without compromising on the low emissions. Additionally, including temperature and humidity sensors to the inner cavity between the outer casing of the gasifier and the burn chamber would assist with getting better reading of the temperature of the air as it enters the burn chamber of the stove.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Acknowledgment is given to Dr. Daliso Banda for valuable guidance during this research. I acknowledge my family and friends for support offered.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML