-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Science and Technology

p-ISSN: 2163-2669 e-ISSN: 2163-2677

2017; 7(2): 41-53

doi:10.5923/j.scit.20170702.02

Implementation of E-health in Developing Countries Challenges and Opportunities: A Case of Zambia

Malunga Gregory, Simon Tembo

Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, School of Engineering, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

Correspondence to: Malunga Gregory, Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, School of Engineering, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

E-Health is being implemented in many developing countries to support healthcare services and the Zambia National Health Strategic Plan seeks to provide the strategic framework for ensuring an efficient, coordinated and well managed health sector by adopting these applications. Despite the national e-Health systems implementation programme covering over 666 out of 1956 representing 34% of health facilities with e-Health applications where 37 are functional model sites representing 1.8%, this adoption rate remains relatively low to achieve meaningful use and can be attributed to many factors. This study was designed to achieve a well-balanced view and experiences among Health Care Providers on e-Health implementation. A health facility institution based mixed methodology was conducted on study participants that were provided with pretested self-administered questionnaires to collect the required data for case analysis. The main content of this paper demonstrates currently e-Health implementation is characterized by high levels of training gaps, lack of a regulatory policy, technology use challenges and many other factors. The output of this research is an integrated e-Health with a new paradigm to information sharing. Although many opportunities exist and are not limited to, but inclusive of stakeholder support, functional e-Health model sites, availability of e-Health training laboratories and government initiatives to implement E-government the challenges still remain unresolved. The study recommends pre and in-service examinable e-Health training curriculum, implementation of a mandatory use e-Health Policy and confront data sharing challenges amongst health care institutions to further encourage adoption of e-Health.

Keywords: Adoption, E-Health, E-government, Meaningful Use, Policy, Training, Zambia

Cite this paper: Malunga Gregory, Simon Tembo, Implementation of E-health in Developing Countries Challenges and Opportunities: A Case of Zambia, Science and Technology, Vol. 7 No. 2, 2017, pp. 41-53. doi: 10.5923/j.scit.20170702.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The Information and Communication technology society has advanced, extending business opportunities to healthcare services and is an enabler to assist healthcare providers, this is imminent that healthcare organizations consider adopting e-Health systems [1]. E-health allows health organizations to streamline many of their processes and provide services in a more efficient and cost-effective manner. Planning to exploit the latest technologies in the healthcare industry is an important strategy for many healthcare organisation and governments to enhance healthcare services so as to reduce operations costs. Many e-Health applications are subjected to different tests to assess the technology adoption impact among users often referred to as meaningful use, derived from different Technology Adoption Models (TAM) that mainly focused on the Perceived Use (PU) [2] of Information Communication Technology artifacts, this is a set of specifications and certification criteria used in e-Health to assess the level of adoption and usage during implementation so as to demonstrate stakeholder participation, progress and performance. Meaningful Use assessments on set measures, menu set measures, bioengineering and clinical quality measures are based on how they can help support decision making through participatory e-health strategy [3] implementation and improvement but other factors like workforce training, technology infrastructure, governance, legislation and policy remain silent elements in the process. There is a compelling need to devise ways and means of closing the gap between vision and reality to provide meaningful use of e-Health in Zambia by providing solution to the missing components [4]. The focus and assessment on the meaningful use of e-Health as the unifying focal point of Zambian e-health vision by the year 2030 [5] is possible, however meaningful use is necessary but not sufficient to harness user resistance of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) to transform healthcare service delivery over the projected time frame.

1.1. Problem Statement

- Despite the implementation efforts on e-Health in Zambia the adoption and usage rates remain relatively low and this calls for an evaluation of the factors that affect effective implementation.

1.2. Research Objectives

- The main objective was designed to achieve a well-balanced view and experiences among Health Care Providers on e-Health implementation in Zambia with the following objectives:-I. An evaluation and review of impact of different e-Health training methods used during implementation in Zambia. II. An assessment of Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Behavioural Intention to Use (BI) of user from different health facilities with or without any implemented e-Health. III. An evaluation of e-Health skills set, knowledge, National health protocols review and acceptance of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) artifacts.IV. An assessment of Infrastructure, Governance, Policy and Regulations mechanism as facilitating conditions to e-Health implementation.

1.3. Research Questions and Hypothesis

- I. What level of impact have the various training methods support the implementation of e-Health?II. What are the different challenges health care providers’ face that contribute to low e-Health adoption levels?III. How can regulations and policy in the National E-Health Strategy help mitigate these adoption challenges?

1.4. Theoretical Framework

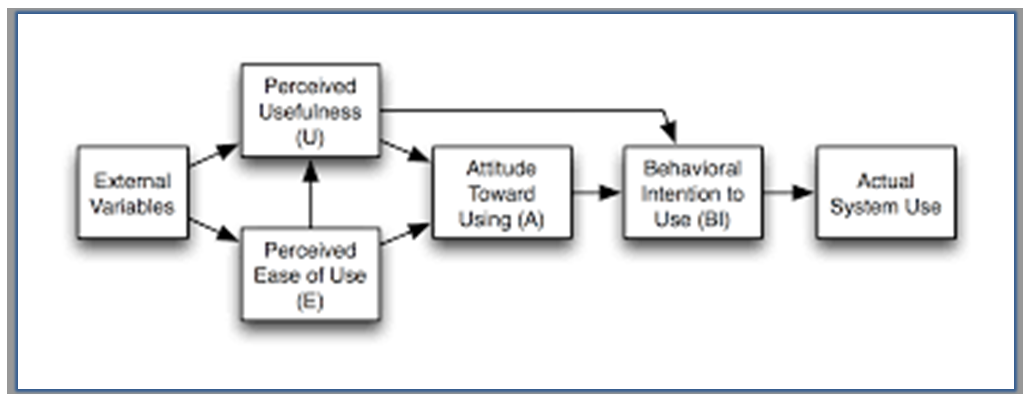

- The study was motivated and guided by Technology Acceptance Theory based on the Theory of Reasoned Action and Human Centered Computing [6] [7]. They suggested that implementation of these technologies need careful assessment of all the factors that affect different professions during pre and post implementation of information technology artifacts, this can be summarised by the essentials variables and flow as indicated in the figure 1 below:-

| Figure 1. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [8] |

2. Literature Review

- According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) and International Telecommunication Union (ITU) [9] defines electronic health system (e-Health) as a computerized medical record used to capture, store, and share information among healthcare providers in an organization, supporting the delivery of healthcare services to patients. The data is collected from the medical records either paper based or electronic and later processed using Health Management Information System (HMIS) [10] for statistical reports. Health Management Information Systems are information based repository on patient disease statistical events, while clinical care health systems handle patient care clinical interactions or medical diagnosis events. The collective systems that can handle both statistical data processing and clinical applications are often referred to as e-Health or Health Information Technologies (HIT). The design and implementation of e-Health Information Technology projects in many developing countries often skip a crucial first step, understanding what the end users of technology need and how they can use technology to address those needs [11]. Software Engineers, Stakeholders and Governments ought to first focus on the roles of health care providers at all levels and how information and communication technology can be an enabler to their jobs or service. Currently Health Management Information Systems holds computed statistical information from different health facilities and patient information detailing the demographics, disease trends and incidences forming part of the epidemiological data but unorganized clinical data exist although the statistics are abstracted from them [10]. These systems depend on the data from medical records, birth and death registration office, Laboratory Information Systems (LIS), Radiology / Imaging Systems and Pharmacy electronic Logistics Information Systems (eLMIS) or from other independent fragmented sources. This type of information processing depends on the output of these independent systems and if well integrated the health sector can use a single system that can share data. These systems can form a collective set of applications that provide different information from a single system and collectively they are often referred to as e-Health. E-health is a required tool to provide accurate patient statistics from patient clinical interactions to support HMIS although in Zambia this currently not functioning optimally [12]. When e-Health systems are subjected to a set of tests and measures they can show adoption and usage levels in the health facilities often referred to as the meaningful use program in developed countries. This assessment is evaluated using different set measures and such measures when not well considered will overlook other factors such as low levels of technology adoption, policy and Information Communication Technology skills or training [2]. The Meaningful Use program targets and include the tasks essential for creating any medical record, including the entry of basic data: patients' vital signs, demographics, active medications and allergies, up-to-date problem lists of current, active diagnoses and any other health related data. The pre implementation assessment is considered vital and must include the human factors for many e-health systems readiness assessment [13]. According to Gamm [14] one major barrier to successfully implement an e-Health system reported by many studies is whether health care providers accept the e-Health systems and the potential disruptions and changes that follow. It has been suggested that health care providers perceived e-health as interfering with clinical workflow, reducing productivity, and introducing disruptive changes to the workplace with such observed tendency is much more serious in developing countries where computer anxiety is very high [15].

2.1. E-Health in Developing Countries

- E-Health offers a more holistic and multi-stakeholder approach to embrace access and availability of ICT that make health facilities more accountable and more responsive to people’s health needs, although lately they were considered primarily an issue of access to relevant information technology infrastructure. According to the pilot e-health implementation phase in Ethiopia, user resistance was reported to be the primary hindering factor to its successful adoption [13]. In the Fourth Health Sector Development Plan, the Ethiopian Government had insisted that e-health system called SmartCarebe implemented in major hospitals and so far the system has been deployed in more than eleven hospitals and clinics with planned scales ups. Similarly the Government of Kenya implemented a National E-health Policy to overcome pre and post implementation challenges [16] as quoted in the policy context annex of e-health strategy that seeks to set in motion the process of closing this gap by harnessing e-health for improved healthcare delivery in addition to other ongoing e-government efforts. Additionally the South Africa government cemented the National Health operation by implementing a National Health Act of 2003 [17] to set operating standards for e-Health Applications. This study therefore aimed to determine the challenges and opportunities in e-Health implementation that affects health care providers in Zambiato bridge the adoption gap, although there are Government efforts to implement and use e-Health inclusive of handling any other associated adoption challenges from health care providers.

2.2. An Insight on Existing Patient Care Information Systems

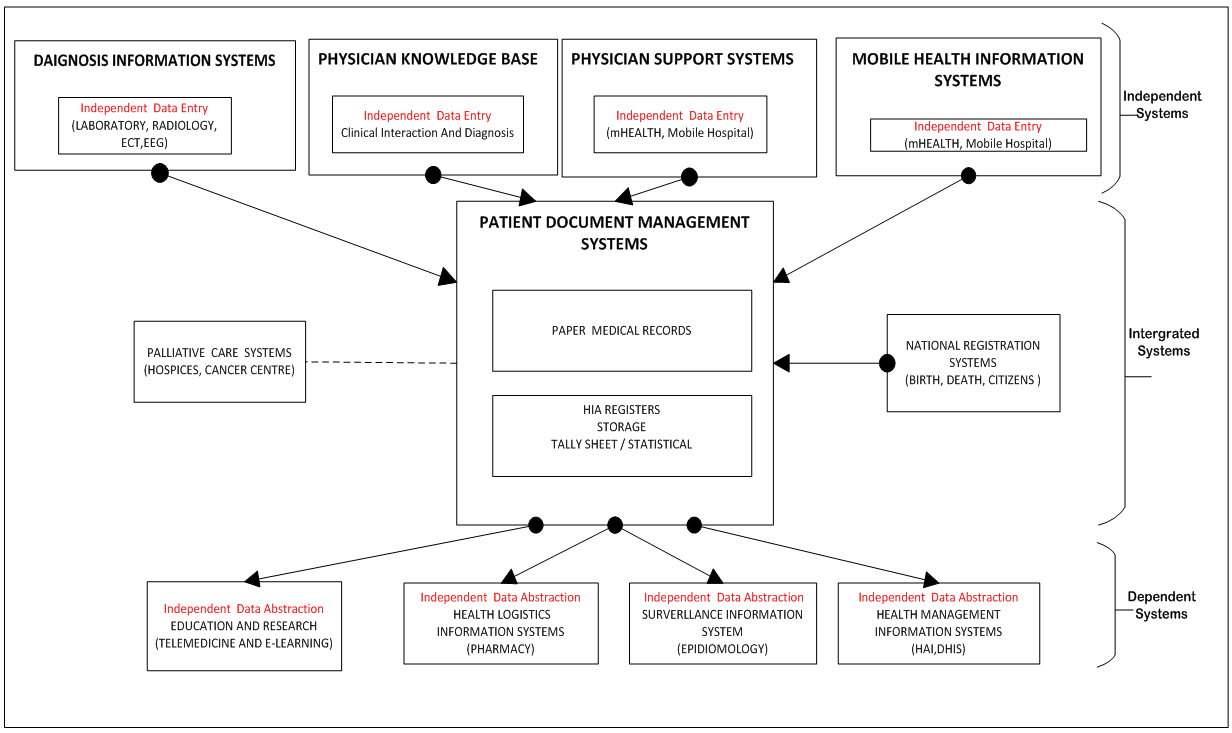

- The current patient information system operates in silos as shown in figure 2 below and every system manages its full data entry, storage and processing of statistical or operation reports. Currently all the health functionalities or services are completed manually and later entered into some available computerised system where applicable and can be viewed from a three level system can be summarised as follows:-

2.2.1. Independent Level

- Comprises of parallel systems operating independently often referred to as specialised departments. Due to the nature of similar patient data captured (i.e. Biodata, Problem listing, Admission and Discharge dates etc.) creates repeated efforts or duplicated manual data entry tasks as show in figure 2 below showing the state of a current operations non-integrated clinical care and data systems:-

| Figure 2. Non-Integrated Clinical and Data Systems |

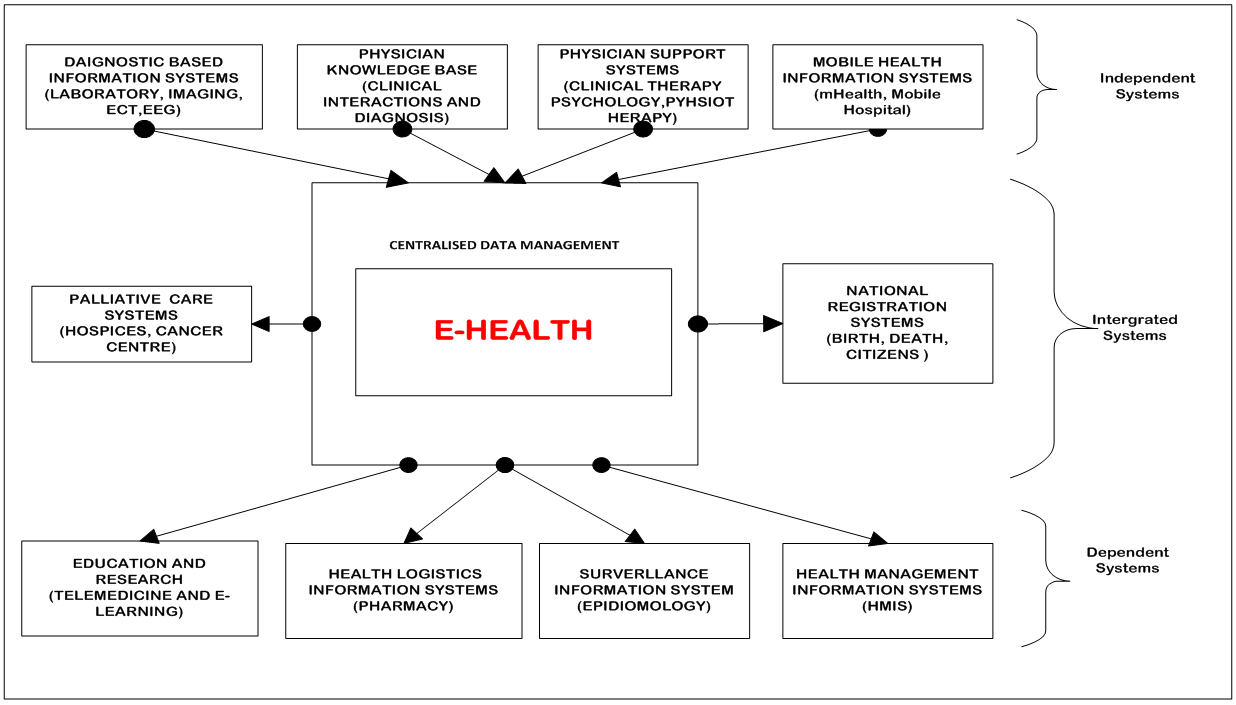

| Figure 3. Contextual view of an integrated e-Health System |

2.2.2. Integration Level

- Embraces systems interoperability with ability to access timely integrated data for improved decision making at various levels of health care service delivery. The core objective is to create a centralized healthcare platform where independent level systems operate as modules feeding into an integrated level system that will operate as a centralized information systems.

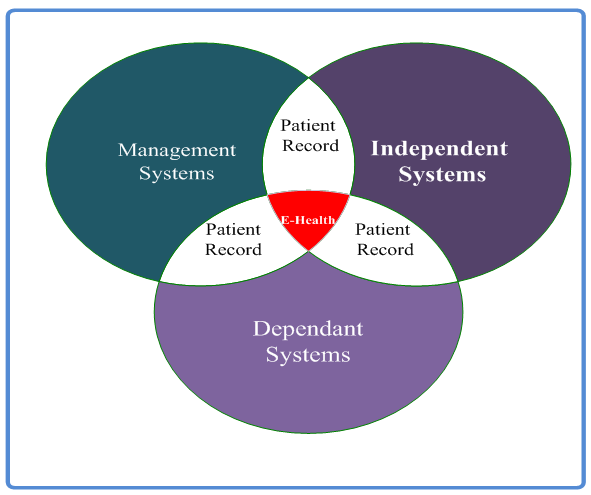

2.2.3. Dependent Levels

- These systems abstract data from independent or integrated systems from various health information infrastructure and workflow to process and form a holistic view of patient care management. In this regard, it identifies various independent but effective technologies necessary to enhance e-Health implementation, based on such collective operation creates a foundation for a review on the current operational approach. The integration of these systems can help form a well-coordinated computerised information system currently referred to as e-Health. The integrated systems that depends on the patient record stems from the above discussed systems and can further be viewed as shown in figure 4 below:-

| Figure 4. An integrated e-Health with a new paradigm to data sharing |

2.3. E-Health Conceptual Framework

- The infusion of ICT in health care delivery calls for Administrative, Legislative and Regulatory framework. The need for suitable frameworks are essential for the implementation of a National or Regional E-Health Project [18] their absence is almost a sure-fire assurance of problems in the medium or long term. According to the WHO [19] the e-Health policy should have a minimum of the following common objectives to qualify as e-Health policy: i. Interjurisdictional practice policy that includes policy provisions, categories and issues to deal with health care information transfer between providers.ii. Networked Health Care policy to enhance the ability of providers, departments, organizations, any jurisdictions to work in a coordinated environment to improve health care of the population.iii. Ethics and Legal Policy in e-Health needs to consider and handle the ethical issues that may arise during adoption.iv. The investment framework includes policy issues that can suggest business models for e-Health adoption. v. The response to new initiatives theme includes policy categories and issues that can enhance the capability of institutions to implement e-Health successfully.vi. Encouraging innovations in technology development, use of technology and general work flows in health facilities.vii. Providing citizens with a chance to access information and further specify the quality of that access in terms of media, retrieval, performance and security.viii. Attaining a specified minimum level of e-Health resources for health educational institutions and government agencies by supporting the concept of lifelong learning.Therefore, a number of these policy goals can effectively be applied to e-Health in Zambia and applying numerous features of National E-Government implementation as building block for health care service delivery.

3. Methodology

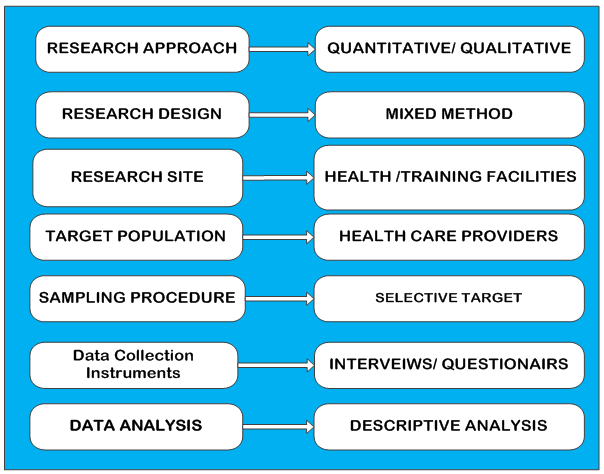

- The Research was conducted from health care and health training facilities across Zambia comprising of Urban and Rural setup, respondents where targeted from these health facilities with partial, abandoned and without e-Health. This case study was designed to achieve a well-balanced responsive view and experiences among Health Care providers on e-Health implementation in Zambia. The research frame work is as shown in figure 5 below:-

| Figure 5. e-Health Research Framework |

3.1. Target Population

- The population size for this research was 39,360 staff returns Ministry of Health based on the 2010 National Health Workers Establishment [20], by working with a confidence level of 95% and 5 as the confidence interval [21]. This research used a sample size of 380 respondents to provide feedback for a good and reliable analysis. The researcher distributed 600 copies with a target of 380 although the final feedback was 302 representing 76% coverage.

3.2. Sample Selection

- The sample selected was a mixed type targeting health care providers from health facilities and teaching hospitals inclusive of health care support staff from information and planning departments. The target was to cover all the 3 levels of operations i.e. Independent, Integration and dependent (Refer to Figures 2 and 3).

3.3. Data Analysis Tool

- The data collected from the study was coded and analyzed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS V21) and covered the above listed research objective (Refer to 1.2 Research Objectives).

4. Results and Analysis

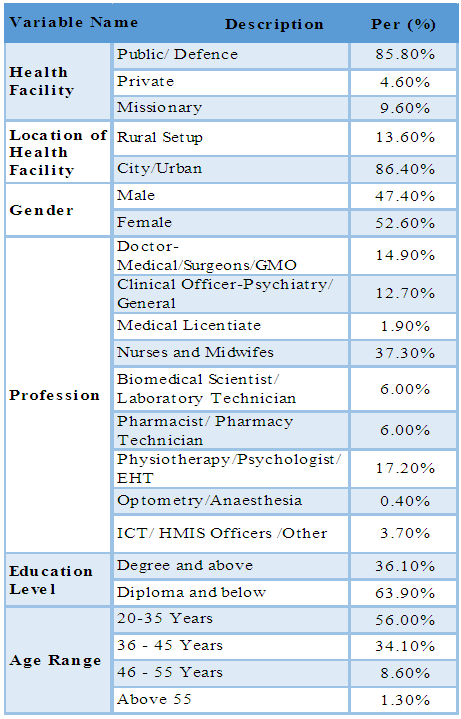

- The Zambian e-Health implementation deployment shows that 666 out of 1956 representing 34% of health facilities have at least an electronic clinical care system according to the 2012 Health Facility Guide [22]. The deployment shows that 37 out of 666 representing 1.8% are Functional Model Sites while 1290 don’t have any Clinical Care Systems, therefore will use any manual or some other form of computerised data capturing, analysis and reporting. The Social and Demographic research characteristic of health care providers refer to Table 1 below shows the distribution of respondent’s and was tailored to get data from health facilities distributed across Zambia as shown figuratively below:-

| Table 1. Social and Demographic characteristic |

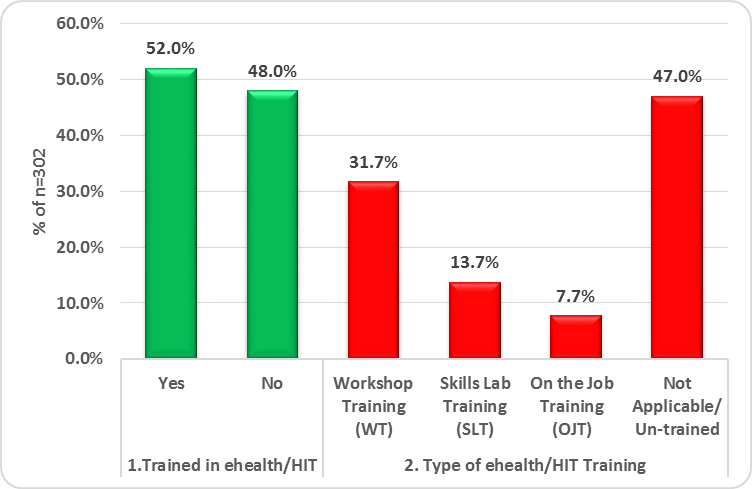

| Figure 6. Analysis of Trained workforce based type of Training |

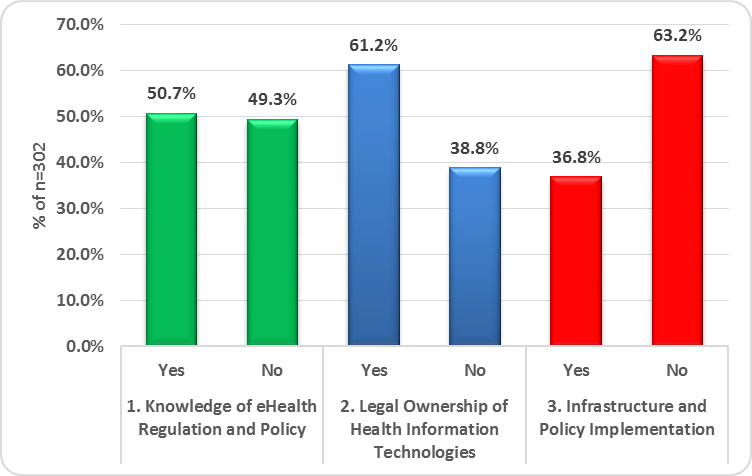

| Figure 7. E-Health Governance, Regulations and Policy and Infrastructure services review |

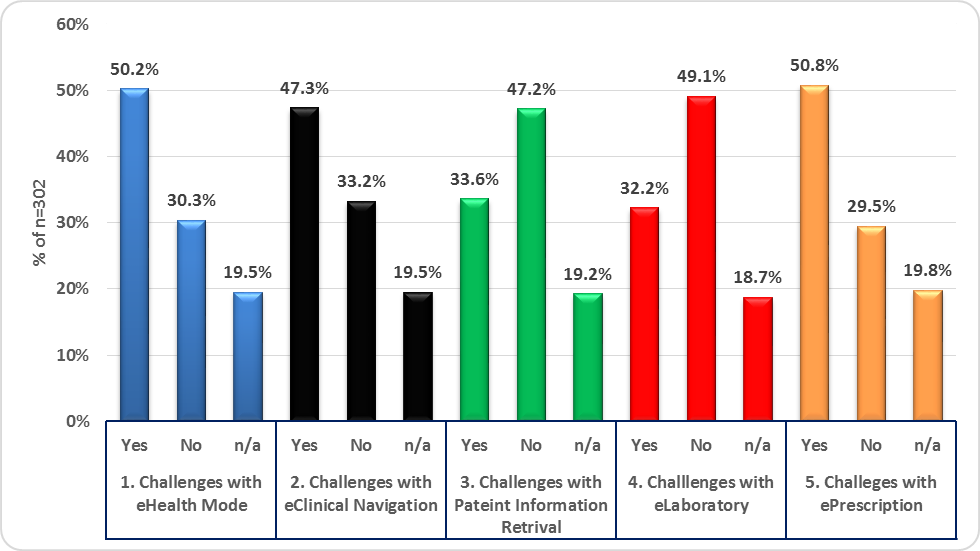

| Figure 8. User challenges with electronic health modules |

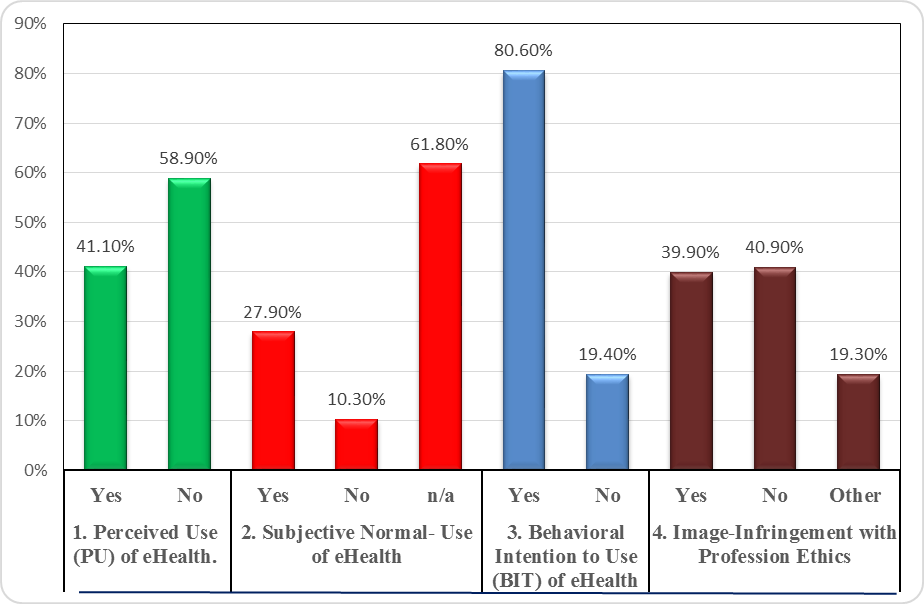

| Figure 9. Perceived Use (PU) overview of E-Health in Zambia |

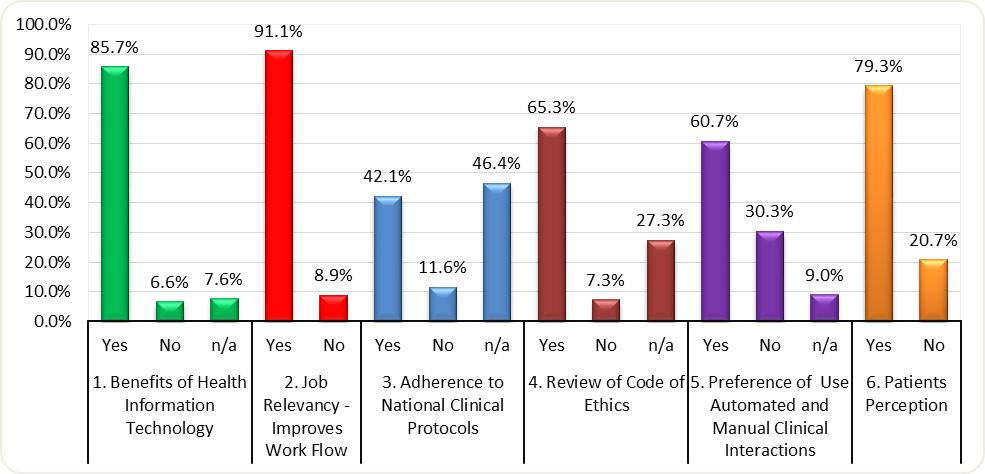

| Figure 10. Analysis of the other factors affecting Health care providers accepting e-Health |

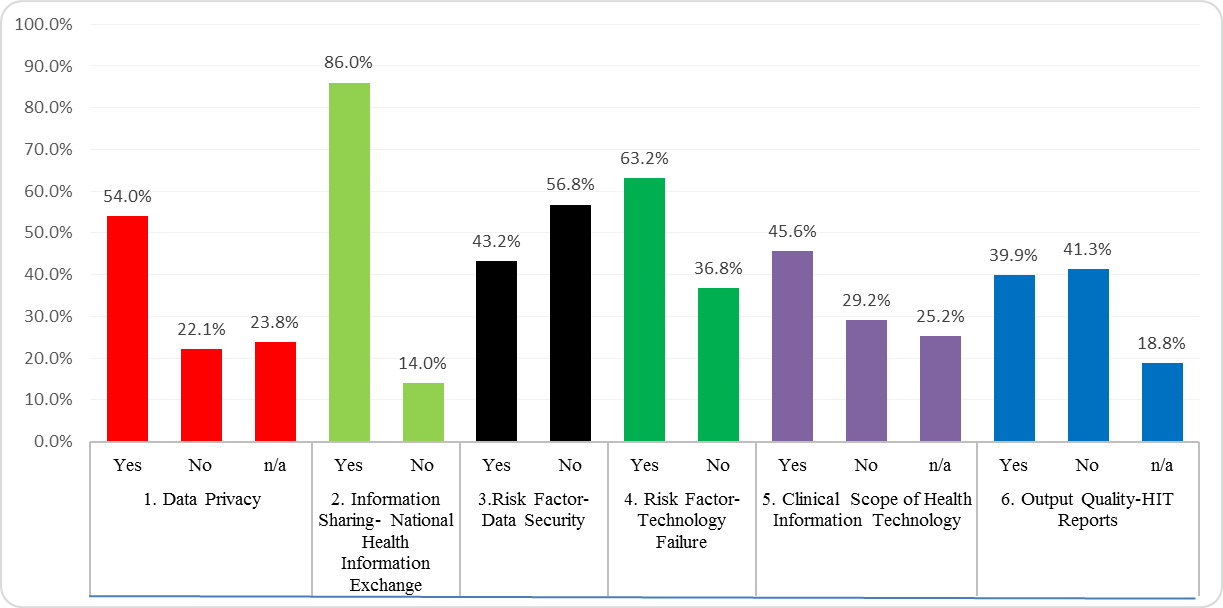

| Figure 11. Other factors that affect or support adoption |

5. Findings and Discussion

- The overall results show that the current e-Health implementation is a “mandated failure” characterized by high levels of training gaps (Refer to Figure 6), indicating that participation in trainings was only and largely symbolic, coupled with a bad internal infrastructure and typically negative adoption attributes (refer to figure 7 and 10). Furthermore the number of medical staff who had no prior training in E-Health could not help in the integration process therefore increasing the adoption bottleneck (Refer to Figure 6) and priority placed on workshop trainings means low skills transfer further impacting implementation programme goals. The current high levels of challenges in e-Health mode among the respondents (including trained healthcare providers) could have further hampered the e-health switch (Refer to Figure 8) confirming that such mixed behavior intention to use patterns can be concluded as a pattern of suspicious technology adoption or use linked to only appease the implementing stakeholders. The current implementation of e-Health is considered as a mere demonstration of a modern health facility that is technologically aware, yet the necessary innovative e-Health environment is lacking for effective meaningful use creating a high patient “local data lock in” situation. Due to different technology failures (Refer to Figure 11) further results in unpredictable use of the technology and institute’s low morale for medical practitioners, who regard the e-Health use as a factor that slows clinical interactions processes and this is backed by the “Optional Use” of the system due to a lack of “Mandatory Use” regulation making the implementation of e-Health extremely difficult. The ongoing system instability in the technology, and lack of responsiveness to user needs limit full adoption of the most e-Health infrastructure. Finally, the research showed that health professional related ethics concerns have an indirect effect on the behavioral intention to use e-Health as discussed in Figure 10 outcome valuation has a non-negligible effect on the health service delivery and concerns to trigger negative behavioral intention to use, on the contrarily stakeholder engagement has been thought as the hindrance but this research shows the most health workers have no problems on who controls the e-Health implementation. The technology failure risk factor exposes another bottleneck of the current e-Health system designed for a non-networked world based on ‘sneaker net technology that confirms an extremely high burden, any failure of one department breaks the health care interaction chain (Refer to Figure 11). Unintegrated patient data represent a national data integrity problem that could compromise quality of care and put patients at high risk. There is a wide range of problems due to isolated patient’s data across healthcare facilities as this does not give a holistic view of the patient ailment for other health care providers and future researchers. Nonetheless, some private controlled facilities have achieved high levels of data integration, and it is important to better understand the factors that contribute to such success to improve patient care as is the case of government e-Health model sites. Private Health Facilities hold valuable data in there e-Health systems that can help unlock better treatment for patients yet this remains privately controlled and restricted therefore breaking the continuity of care programme. It is inevitable for private organisation to contribute to the development of such application and ensure that their current systems can easily integrate and or share information with the Public controlled E-Health systems. Furthermore the Ministry of Health initiatives should include creating e-Health national standards for patient forms tailored for e-Health systems to have great potential to streamline care, in this case by reducing the number of forms that health personnel are required to fill out on a regular basis allowing them to focus on their clinical duties as this has impacted on the complex design of the National E-Health System. These measures and others will go a long way in creating and bridging to a more efficient e-Health system. The Zambian Government is clearly aware of these needs, and is making inroads into creating a coordinated set of systems although these efforts are unknowingly derailed during implementation. Furthermore there is need to shift from the model site implementation strategy (This is proving to be successful but are operating in isolation) to mandatory policy use through clear governance and management structures for the success of the e-Health Strategy. The reason is that the deployment strategy is not linked to clear goals or supported by systematic monitoring and evaluations. It is critical to have a plan on how to maintain and grow E-Health over time but the current trend in Zambia is that health care providers are entering patient medical information into various E-Health systems confirming and demonstrating that electronic data collection at health facilities is possible at point of patient care. Most of the data is flowing in stakeholder’s E-Health platforms reliably at the national level through implementing partner control and management, while the same applications help they are scheduled at the same time, risking the success of implementation because of targeting the same health practitioners but controlled by different implementing partners. This demonstrates that data flow is possible with the right policies when good business processes are in place. Lack of key processes and supervision through the ministry system relegate most of the E-Health systems to an “optional” system or a system “for implementing partners”. This data flow will leverage and promote the uncompromised adoption of the system at all levels, limiting reliable data collection at the facility, including poor data flow and use through the health system. The National E-Health Policy needs to define a clear e-Health product strategy that is tied to the overall National Health Policy implementation strategy, that show what the technology is and is not, what it should and should not do backed by ICT technical leadership. Inadequate Health Information Technology management and software development processes in another cause of a current issues harbored by persistent system instability, Lengthy timelines to fix system failure backed high power failures. Inability to monitor data quality, ongoing bugs, issues with reports, and incorrect indicator calculations limit confidence in the reliability of the data and reports (Figure 11). Additionally undermining simple clinical scope forces trained health workers to revert back to manual or paper based system for fear of misdiagnosis due to the complex design or inconsistent work flow in e-Health systems. Long-term review indicate that early versions based on departmental functions were simpler, more usable, and captured data more reliably, but current e-Health design is complex thus making data entry time consuming and distracts patient clinical interactions. Overall the current e-Health systems data are not integrated with other key information systems (e.g. HMIS), limiting usefulness and forcing users to access multiple systems for similar purposes to compile reports and integrate patient summary case notes. The later prompts the need to design e-health platforms that handles both a non-networked and networked care health system is vital to reduce the high burden of effort to physically transmit and combine data from independent sub systems or silos. The other important element is Certification based on Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) of e-Health to ensure that providers can be assured they are capable of developing and implementing meaningful use compliant applications. The Zambian Government should also provide policies and regulations that tables the standards and certification criteria that National E-Health Strategy must accept in order to be e-Health ready or certified.

6. Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Summary

- The Meaningful Use (MU) of e-Health drawback should not only be characterized by the core meaningful use requirements but include other factors e.g. Levels of training, Information sharing, complex technology design and availability of adequate policies or a regulatory framework. The study highlights the need for a formation of regulatory body or subcommittee in the ICT regulatory bodies or the Ministry of Health to ensure examinable training curriculums are incorporated at health training institution level. Secondly the health ministry must pay particular attention to the training and education of medical staff who are the core users of the technology with a focus on nurses and midwives who are the major player in the clinical cycle. National awareness campaigns that are designed and implemented communicating the scope and benefits of e-Health, so as to eliminate lack of high-level advocacy within Ministry of Health for e-Health control because many systems do not receive appropriate supervision, focus and resources but are stakeholder driven. Mandatory Use of e-Health systems policy to erase the perception by users who feel they are stakeholder controlled systems and this undermines the Ministry of Health ownership because they offer subjective conditions or offers “use and benefit or lose it” strategy.

6.2. Conclusions

- Based on the research findings on e-Health and summarized according to the Zambian context. This paper give details on the current status of e-Health in the country with reference to the various literature. The study opens an insight, highlights the state of e-Health in Zambia with a particular view to customise it so that it becomes inclusive in the National e-Health Policy that will regulate software as asserted by Coiera and Enrico [23]. The research confirms that e-Health core design and information products are so far considered adequate but workforce training, clinical compliance, governance, regulation and policy and change management remain very poor coupled by inadequate ICT infrastructure. The capacity of health facilities to generate, analyse, disseminate and use e-Health differs [24] and this research can conclude that the overall e-Health in Zambia is poorly implemented caused primarily by lack of extensive research in the field, therefore this calls for more research to be conducted prioritising the components that highly affects and contributes to the development of National e-Health Strategy [16]. The national regulations must be both ambitious and fully achievable, although the speed of scaling up must be regulated to reflect both the capacities of health care providers who face a multitude of real-world challenges and the maturity of the Zambia’s e-Health infrastructure on the one part, so as to help reduce data and clinical errors rate were significant focus is to reduce and increase a decline in non-observed serious clinical errors. System-related errors require close attention as they are frequent, but are potentially remediable through system redesign and extensive user training. Finally the Government of Zambia should move away from strategic and programmatic system implementation to a regulatory policy framework strategy. E-Health training programs for health care providers rollout should begin at the training institution unlike work-place as this divides implementation and training time on the job against performing actual work. While many implemented systems, such as Health Management Information Systems (DHIS2), Cancer Registry Management Software (CanReg 5 currently implemented in 9 Provincial Medical Offices), NicVue ® Electroencephalogram (EEG) found in most hospitals, Electronic Logistic Information Management (eLMIS) and SmartCare exhibit great isolations, they also demonstrate commitment to an E-Health infrastructure implementation and a chance to evaluate current systems to support National E-Health Policy. Experiences from these E-Health systems can simultaneously help to gate to speed into a relatively advanced health care system, although they can be limited by the same factors and opportunities that affect other E-Health implementations projects. Open Source software standards and code reuse can provide a better coexistence of systems unlike promotion of the Commercial off the Self (COTS) application often used in the private sector and locked up to vendor license agreements. This strategy can provide the government an approach to open source alternatives applications that meet public and private sector requirements therefore the end result is an integrated e-Health with a new paradigm to information sharing.

6.3. Recommendations

- The findings are of value to Government of Zambia, health care providers, health service delivery organizations, and private health care facilities to use this paper as a framework to conduct and develop governance, legislation and polices, prepare new curriculum and workforce training. The following recommendations needs to be considered as a foot print to leap frog to successful e-Health implementations:(a) There is need to review, enhance or change the current workforce training methodology based on workshops supported by in-service knowledge transfer through O the Job Training (OJT) to a full Tertiary/ College ICT Skills training, because the later does not offer a comprehensive knowledge base to ensure that health care providers are equipped with necessary e-Health skills. (b) There is need to measure knowledge, competencies and skill rather than numbers trained to pre-service trainings based on examinable and practical curriculums. (c) Essential e-Health skill sets and experience are weak or missing and needs deep Information Technology expertise and deployment using change management through well-defined ICT business processes and communication that stems from sufficient training and acceptance of technology by health care providers. (d) Trained health care providers should be monitored through continuous professional development (CPD) because the amount of patient data being captured will increased substantially overtime to ensure data quality in e-health applications.(e) Implement e-Health technology that allows scalability and inter-operability with other existing systems.(f) Move to a fully regulated implementation “Mandatory Use” policy as many health care providers regard the current e-Health as “Optional Use” systems.(g) Identify challenges that confront e-Health systems and carefully devise mitigating strategies in a National e-Health Strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I am very grateful to my supervisor Dr. Simon Tembo for this research take shape and allowed me to work on it tirelessly because of his great encouragements and support. Many thanks to the following health and training facilities in Zambia namely Levy Mwanawasa General Hospital, Chainama Hills College Hospital, University Teaching Hospital, Saint Luke’s Mpanshya Mission Hospital, Zambia National Cancer Registry, Maina Soko Military Hospital and the Ministry of Health for their clearance and support. I wish to thank my family and all respondents for their selflessness and support rendered to me and made this research publication possible.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML