O. D. Oyeyinka1, L. A. Dim2, M. C. Echeta1, A. O. Kuye1

1Centre for Nuclear Energy Studies, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

2Centre for Energy Research and Training, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

Correspondence to: O. D. Oyeyinka, Centre for Nuclear Energy Studies, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Critical infrastructure, which includes nuclear and radiation facilities, power, banks, transportation, national gas and oil distribution and telecommunications systems, are the bedrock of modern societies; their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof. Our dependence on critical infrastructure makes them attractive targets for attack. A deliberate act against a nuclear and radiation facility could directly or indirectly endanger public health and safety through exposure to radiation. Physical Security Systems (PPS) are deployed to prevent or mitigate loss of valuable assets. The effectiveness of physical security systems is evaluated as the probability that the security system defeats an adversary along a given path. This work examined the structure of the PPS of a Nuclear Energy Centre (NEC) in Nigeria. NEC consists of three main assets (asset 1 - nuclear science and engineering laboratory; asset 2 - thermal hydraulic laboratory and asset 3 - a research reactor). Estimation of Adversary Sequence Interruption (EASI) and Dai et al [1] models were used for quantitative evaluation of the PPS of the NEC. The probability of interruption obtained for the security systems is 0.930 using EASI model. The results of system effectiveness using Dai et al [1] model for asset 1, 2 and 3 were 2.6494, 2.7315 and 3.5389 respectively. The corresponding associated risks for asset 1, 2 and 3 were 0.0283, 0.02324 and0.3647 respectively and total risk of the NEC multiple assets is 0.0880. The results showed that the security system is high (low associated risk for the assets) since the Probability of interruption is greater than the medium security system range of 0.50-0.75. This work will serve as base guidelines for the decision makers for the application and evaluation of PPS and provision of counter measure strategies in the nuclear energy centre and other nuclear/radiation facilities in Nigeria.

Keywords:

Security System, EASI Model, Information Entropy, Physical Protection System, Risk Assessment

Cite this paper: O. D. Oyeyinka, L. A. Dim, M. C. Echeta, A. O. Kuye, Determination of System Effectiveness for Physical Protection Systems of a Nuclear Energy Centre, Science and Technology, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 9-16. doi: 10.5923/j.scit.20140402.01.

1. Introduction

The significance of security to mankind cannot be over-emphasized as the socio-economic structure of any society or organization depends on the security system available in such society or organization [2]. Physical Security Systems are deployed to prevent or mitigate loss of valuable assets (e.g., property or life) [3]. Hence, human beings and societies since the beginning of time have developed measures to safeguard themselves and their properties against threat [2]. A Physical Protection System (PPS) integrates people, procedures, and equipment for the protection of assets or facilities against theft, sabotage or other malevolent attacks [2, 4, 5; 6]. Kano, Zaria, Ile-Ife and other ancient city walls built hundreds of years ago in Nigeria confirmed the recognition of physical protection in Nigeria before the advent of the modern security technology. However, a change in the way in which houses were built within the walls indicates that the first occupants may have been conquered. This means some adversaries devised a method to defeat the protection offered by those first walls. Also, the cycle of violence being unleashed on Nigerians by religious extremists has heightened fears among the populace and the international community that the hostility has gone beyond religions or political colouration. The insecurity challenge has become a great source of worry as security experts affirm that what is on ground has shifted to the realm of terrorism [7]. After the September 11, 2001 attacks, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) determined 1that additional security measures should be put in place during the transport of spent nuclear fuel (SNF) and those current security regulations should be enhanced to further protect SNF during transport [6]. During the past decade, the need for improving physical protection of nuclear material has been felt increasingly in science and international security. Concerns about the security of nuclear materials have been raised in view of a wide distribution of orphan radiation sources [7, 8] and a dramatic increase in the illicit trafficking of nuclear materials worldwide, doubling the 1996 annual rate of reported incidents in less than half a decade [9], with threats of international nuclear terrorism rapidly developing [10]. Many factors can lead to loss of control of radioactive sources, including ineffective regulations and regulatory oversight; the lack of management commitment or worker training; poor source design; and poor physical protection of sources during storage or transport [11]. The challenge is to address this wide range of risks with effective actions [12]. Effective physical protection requires a designed mixture of hardware (security devices), procedures (including the organization of the guards and the performance of their duties) and facility design (including layout) [1]. Nuclear and radiation facilities may be vulnerable to adversary attack and in extreme cases lead to substantial releases of radioactive materials with consequent loss of lives, radiation sickness and psycho trauma, extensive destruction and economic disruption. Therefore, there is a need to have an effective physical protection system design and evaluation that can protect the facilities against terrorism, sabotage and natural disaster.The aim of this work is to ensure the desired degree of physical security to prevent the accomplishment of overt and covertly malevolent actions at a Nuclear Energy Centre (NEC) in Nigeria. The specific objectives include evaluation of the current status of the physical protection system and the quantitative risk assessment for assets within NEC.

2. Methodology

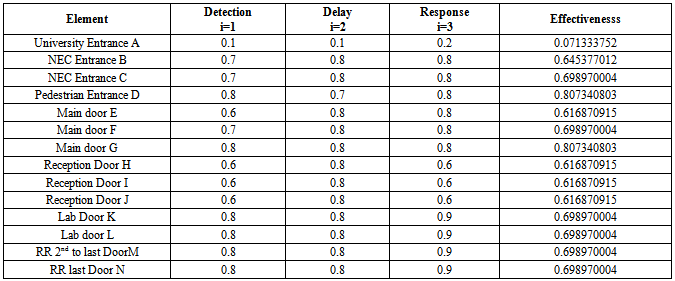

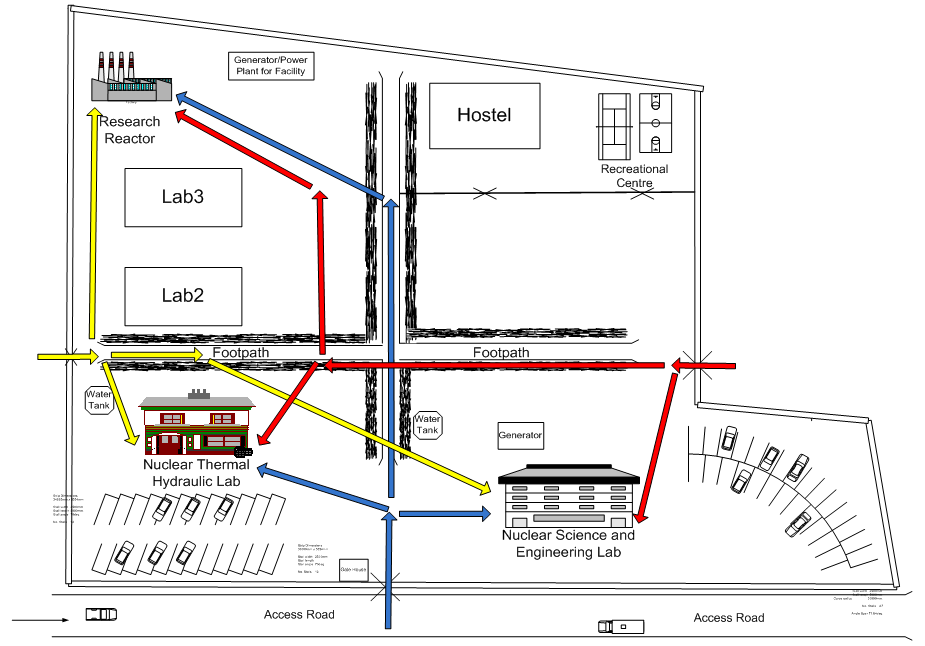

NEC is located within a University. The University has two main entrances. NEC can be accessed through any of these university entrances. The NEC facility, which is shown in Figure 1, is fenced and consists of three main assets. The assets are:Asset 1: Nuclear science and engineering buildingAsset 2: Thermal hydraulics buildingAsset 3: Research reactor buildingEach asset has a main door, a reception door and a door for each room where specialized and sensitive equipment or nuclear materials are housed. In addition, a second protective door is provided for the research reactor. Access to the NEC is through the main entrance A, vehicular entrance B and a pedestrian entrance C. There are also plans to build two other laboratory buildings; these are designated as Lab2 and Lab3 in Figure 1.  | Figure 1. Diagram of Security System in the Nuclear Energy Centre Scenario |

2.1. Risk Assessement for Single Assets

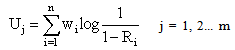

The risk assessment methodology used for security systems that protect single asset consists of a number of steps; the steps are as follows:Step I: Identify the threat(s) to be evaluated.Step II: Obtain physical and operational data as well as analyse facilities and operations.Step III: Develop the threat specific path sequence diagram.Step IV: Apply the Estimate of Adversary Sequence Interruption (EASI) model to predict the likelihood that the threat will succeed. EASI is a fairly simple calculation tool developed by Sandia National Laboratories, USA. It quantitatively illustrates the effect of changing physical protection parameters along a specific path. It uses detection, delay, response, and communication values to compute the probability of interruption P1. Since EASI is a path-level model, it can only analyze one adversary path or scenario at a time. It can also perform sensitivity analyses and analyze physical protection system interactions and time trade-offs along that path. In this model, input parameters are the physical protection functions of detection, delay, and response and communication likelihood of the alarm signal. Detection and communication inputs are in form of probabilities (PD and PC respectively) that each of these total functions will be performed successfully. Delay and response inputs are in form of mean times (Tdelay and RFT respectively) and standard deviation for each element. All inputs refer to a specific adversary path [4]. The output is the P1, or the probability of interrupting the adversary before any theft or sabotage occurs. PI is given as:  | (1) |

Where PC is Probability of Guard communication, PD is Probability of sensor detection.Evaluation of many systems designed and implemented by Sandia National Laboratories indicates that most systems operate with a PC of at least 0.95. This value was used for the present work. It should, however, be noted that PC is influenced by factors such as lack of training in use of communication equipment, poor maintenance, dead spots in radio communication, or the stress experienced during an actual attack. The values of probability of detection are based on the availability/non-availability of sensor(s) on the adversary paths. Delay and response values, in form of mean times and standard deviation for each element are purely expert opinion based on security guards’ drills [12, 22]. Step V: Evaluate the acceptability or otherwise of the assesssed risk. If necessary, revise the facility design, operations, technology and/or assumptions.

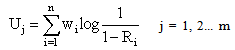

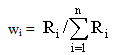

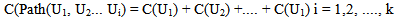

2.2. Risk Assessement for Simultaneous Multiple Assets

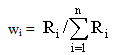

This methodology used for assessing security systems that protect multiple assets are presented in details by Dai et al [1]. The main steps are:1. Identify the assets, security units and intrusion paths; 2. Determine the protection effectiveness of the security unit using equation: | (2) |

Where Ri = Probabilities of i (i=detection, delay or response). The probability is 1 when the protection task is fully met. The probability is 0 when the task is absolutely not met.  3. Determine the protection effectiveness of an intrusion path:

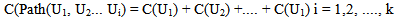

3. Determine the protection effectiveness of an intrusion path: | (3) |

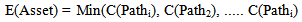

4. Assess the risk of the security system. The most vulnerable path is the minimum cost of intrusion paths for each asset. Hence, the protection effectiveness for each asset is given as | (4) |

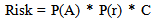

5. Compute the risk of the security system using [19]: | (5) |

Where P(A) is the probability of attack against a critical asset during the time frame of the analysis which can be assessed by experts. C is consequence; P(r) is the probability of successful attack that is also called the probability of protection invalidation. It can also be shown that [1]: | (6) |

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Measuring the Effectiveness of the Physical Protection System Using EASI Model

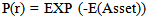

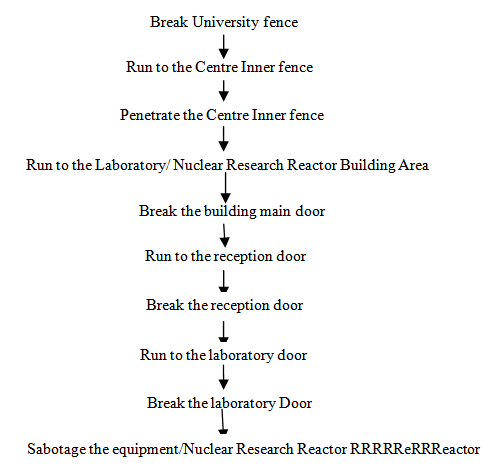

The main assets are the three buildings at NEC. As stated earlier, these assets consist of equipment and research reactor. The paths to each of the assets are also shown in Figure 1. The general threat specific path sequence diagram for sabotaging and/or theft of any of these assets is as shown in Figure 2.  | Figure 2. A PSD diagram for any asset in the NEC |

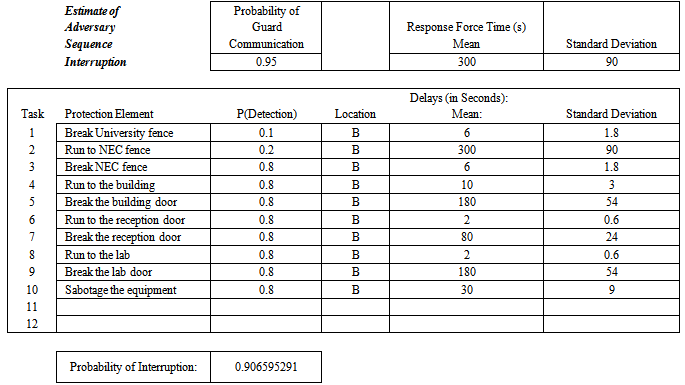

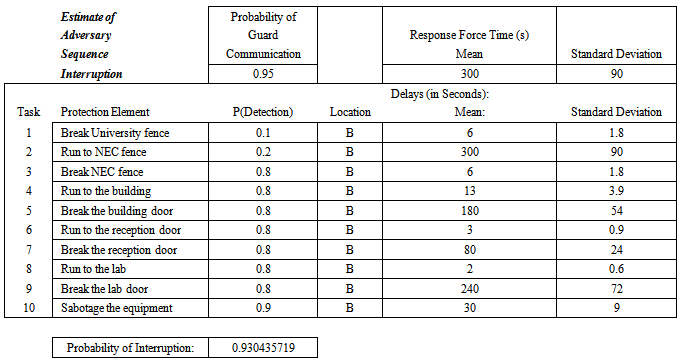

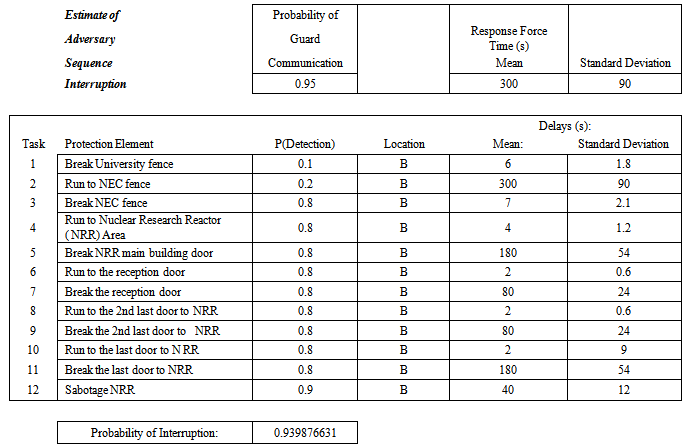

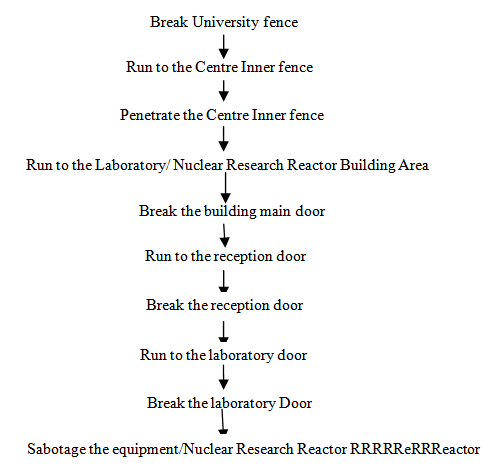

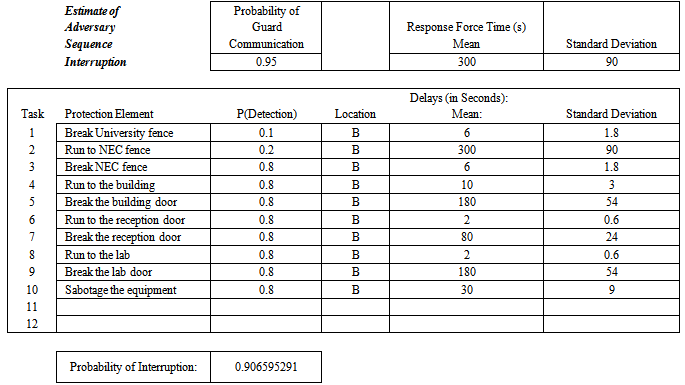

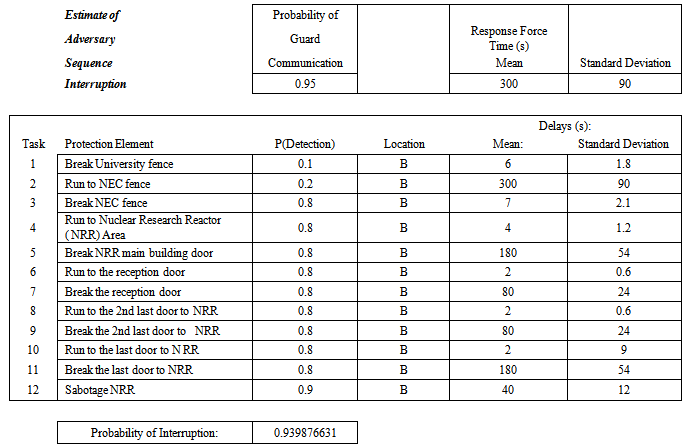

Using Figure 1, the path of an adversary is shown in Table 1, 2 and 3 for Assets 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Also shown are the expected probability of detection values; delay times; response force time; detector location and the calculated probability of interruptions. In these tables B means that only cameras are used as detectors and are located at the beginning of each protection element. The standard deviation (SD) for the response force time and the adversary mean delay time are the values are calculated by the EASI program when the other values are entered as indicated in the tables. As can be seen the SD values are approximately 30% of the corresponding mean values. The probability of interrupting the adversary before any theft or sabotage occurs at asset 1, 2 and 3 are 0.9066, 0.9304 and 0.9399 respectively. The results showed that the security system is high (low associated risk for the assets) since the probability of interruption is greater than the medium security system range of 0.50-0.75 [4].Table 1. Results of Estimate Adversary Sequence Interruption (EASI) Analysis of the Asset 1

|

| |

|

Table 2. Results of Estimate Adversary Sequence Interruption (EASI) Analysis of the Asset 2

|

| |

|

Table 3. Results of Estimate Adversary Sequence Interruption (EASI) Analysis of the Asset 3

|

| |

|

3.2. Measuring the Effectiveness of the Physical Protection System Using Dai et al [1] Model

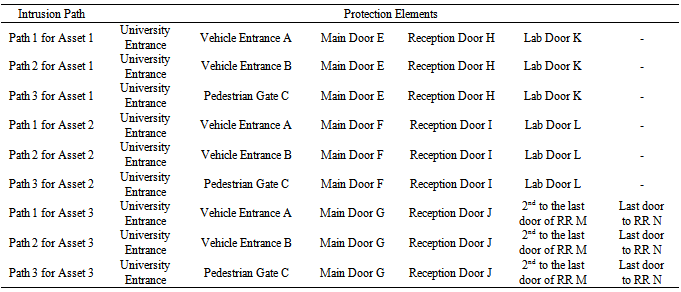

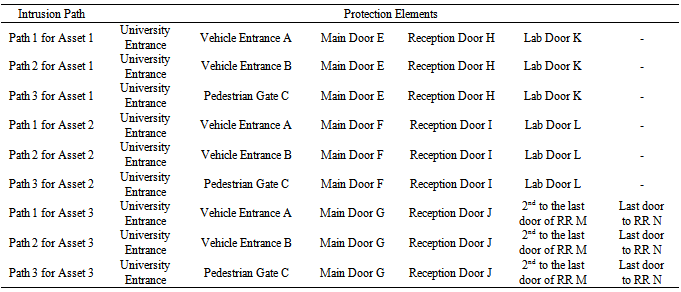

As indicated in Figure 1, there are three paths to access any of the three assets from outside NEC fence. These are penetrations of the adversary through vehicle entrance A, vehicle entrance B and the pedestrian gate C. Table 4 shows the possible paths an adversary may take to attack the nuclear energy centre. Table 4. The protection elements of each intrusion path

|

| |

|

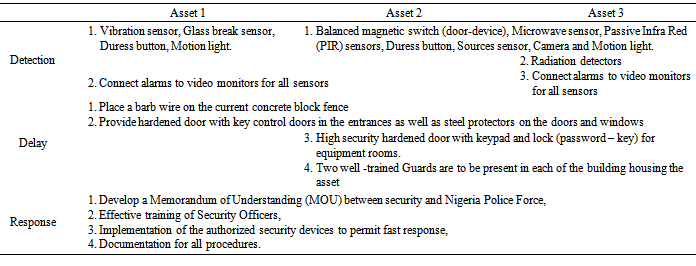

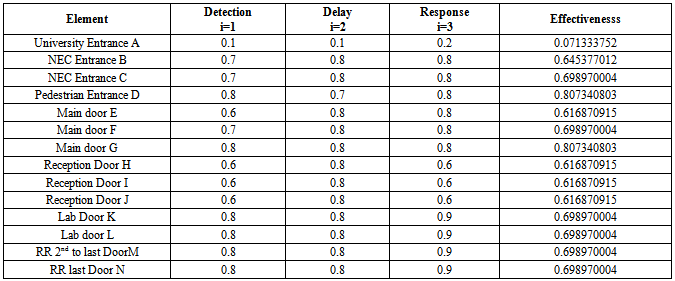

The effectiveness of each element was calculated using equation (2) and shown in Table 5. The probabilities of detection, delay and response were based on expert judgments of the performance of the detectors, delay and response functions when evaluated through security drill exercises. Table 5. Effectiveness of Each of the Security Element

|

| |

|

The calculated effectiveness for each intrusion path in Table 4 using equation (3) is shown in Table 6. Table 6 shows the protection capabilities of each of the intrusion paths, the higher the number of security units in an intrusion path; the greater the cost an attacker must pay to be successful at the nuclear energy centre. | Table 6. The Effectiveness of Each Intrusion Path |

| | Intrusion Path | Effectiveness | | Path 1 for Asset 1 | 2.649423 | | Path 2 for Asset 1 | 2.703016 | | Path 3 for Asset 1 | 2.811386 | | Path 1 for Asset 2 | 2.731522 | | Path 2 for Asset 2 | 2.785115 | | Path 3 for Asset 2 | 2.893485 | | Path 1 for Asset 3 | 3.538862 | | Path 2 for Asset 3 | 3.592455 | | Path 3 for Asset 3 | 3.700826 |

|

|

From Equation (4) the effectiveness of the security system are: E(asset 1) is 2.649423; E(Asset 2) is 2.731522; and E(Asset 3) is 3.538862. Assuming that the annual rate of occurrence of attack for the asset 1 is 0.8, for asset 2 is 0.8 and Asset 3 is also 0.8; the calculated risk for each asset are shown in Table 7. From Table 7, the total risk based on the three Assets of the Nuclear Energy Centre security system can be calculated as 0.087981| Table 7. The risk of each Asset |

| | Parameter | i = 1 | i = 2 | i = 3 | | E(Asseti) | 2.649429 | 2.731522 | 3.538862 | | P(Ai) | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | | Ci | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | | Riski | 0.028277 | 0.036467 | 0.023237 |

|

|

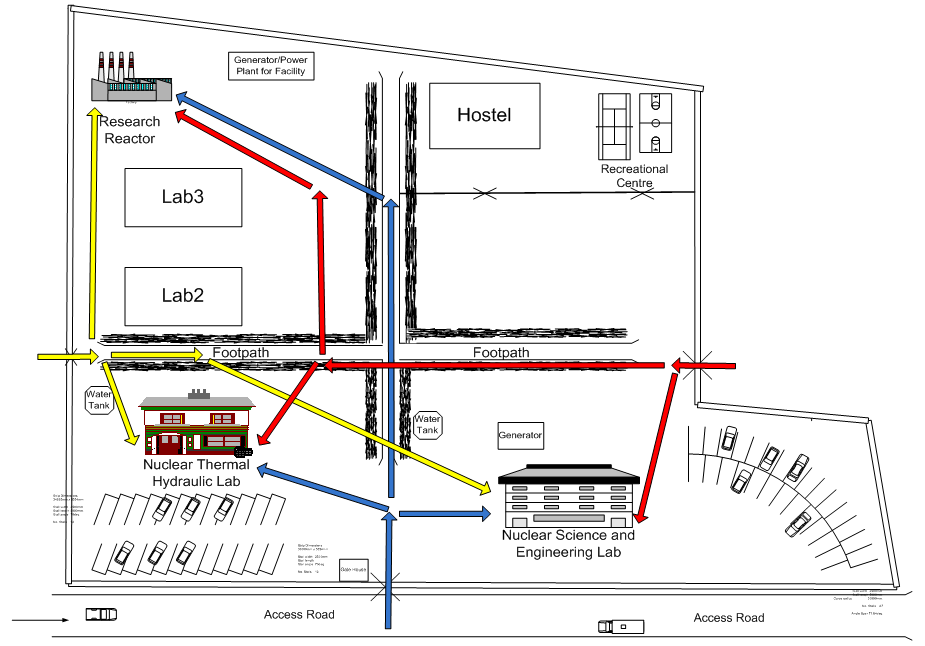

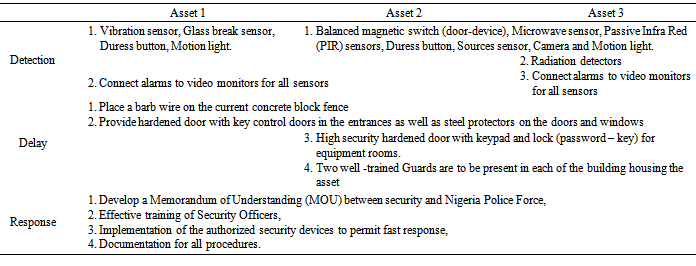

3.3. Suggested Improvements in the PPS and Design Criteria

The results presented in Sections 3.1 and 3.2 indicate that the risks are low. However, a critical look at NEC reveals that possible threats to NEC assets include theft, sabotage, radiological dispersion/radionuclide contamination, criminal activity, natural disasters and terrorist’s acts. In line with global best practices an effective PPS would address the following factors:i. Access control - minimum access to and the number of access points into the protected area and vital area(s). ii. Predetermination of trustworthiness - to require unescorted employees to have a security clearance or an authorization appropriate to their level of access.iii. Vehicle search and forceful intrusions - to check the vehicles and take measures to reduce the risk of forced vehicle penetration into a nuclear facility. iv. Tampering of equipment and records - to detect tampering or interference with equipment system or devices and take special precautions during and following shutdown or maintenance. v. Placement security guards - to establish an armed response force available at all times and capable of making an immediate and effective intervention to counter threats to NEC.vi. Contingency planning, drills and exercises - to test physical protection systems through regular drills, and develop and exercise contingency plans to manage anticipated security related emergencies.vii. Detecting equipment - to maintain the operation of alarm systems, alarm assessment systems, and the various essential monitoring equipments in the security monitoring room. viii. Communication system–to consistently communicate within and outside the facility [14, 23].With these factors taken into consideration, suggestions for improving the detection, delay and response functions for assets 1, 2 and 3 are summarized in Table 8.Table 8. Suggested improvements for PPS at NEC

|

| |

|

4. Conclusions

The ultimate goal of a PPS is to prevent the accomplishment of overt and covert malevolent actions. This work developed an analytical methodology for PPS evaluation. Effectiveness of the physical protection system in a nuclear energy centre was determined using the computerized Estimation of adversary Sequence Interruption (EASI) model for single protected asset and Dai et al [1] model for multiple protected assets. The probability of interruption obtained for the security systems is 0.930 using EASI model. The results of system effectiveness using Dai et al [1] model for asset 1, 2 and 3 were 2.6494, 2.7315 and 3.5389 respectively. The corresponding associated risks for asset 1, 2 and 3 were 0.0283, 0.02324 and0.3647 respectively and total risk of the system as multiple assets is 0.0880. The results showed that the security system is high (low associated risk for the assets) since the Probability of interruption is greater than the medium security system range of 0.50-0.75. This work will serve as base guidelines for the decision makers for the application and evaluation of Physical Protection systems (PPS) and provision of counter measure strategies in the nuclear energy centre and other nuclear/radiation facilities in Nigeria.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Nigeria Atomic Energy Commission (NAEC) for sponsoring this research work.

References

| [1] | Dai, J; Ruimin, H; Chen, J; Cai, Q (2012). Benefit-Cost Analysis of Security Systems for Multiple Protected Assets Based on Information Entropy, Entropy, 14(3), pp571-580. |

| [2] | Omotoso, O; Aderinto A. A (2012).Assessing the Performance of Corporate Private Security Organizations in Crime Prevention in Lagos State, Nigeria, Journal of Physical Security Vol.6:1, pp.73- 90. |

| [3] | Graves, G.H (2006). Analytical foundations of physical security system assessment. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, pp. 1-80. |

| [4] | Garcia, M. L (2007).The Design and Evaluation of Physical Protection Systems, Second edition, Sandia National Laboratories, pp. 1-375. |

| [5] | Jangs, S.S; Kwak, S; Yoo, J.K; Yoon,W (2009). Development of a Vulnerability Assessment Code for a Physical Protection System: Systematic Analysis of Physical Protection (SAPE). IN: Nuclear Engineering and Technology, VOL.41, pp. 747-752. |

| [6] | Yang, Z (2011). Research on the Effectiveness evaluation and Risk Optimization of Crime prevention system based on Fuzzy Theory and AHP model, Journal of Computers, Vol 6:2.pp. 232-239. |

| [7] | Achumba, I.C. Ighomereho, O. S. Akpor-Robaro, M. O. M. (2013) .Security Challenges in Nigeria and the Implications for Business, Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, Vol.4, No.2, 2013 pp.79-99. |

| [8] | Ortiz, P.; Friederich, V; Wheatley, J; Oresegun, M. (1999). Lost and found dangers: orphan radiation sources raise global concern. IAEA Bulletin 41: 3, pp. 18-21. |

| [9] | Geiger, G; Schaefer, A (2004). Approaches to Quantitative Risk Assessment with Applications to physical protection of nuclear Materials, Journal of Physical Security Vol 1 No 1:4, pp. 1-36. |

| [10] | IAEA, (2001).Nuclear Security and Safeguards. IAEA Bulletin 43, No. 4.pp2. |

| [11] | Nielsson, A. (2001). Security of material: the changing context of the IAEA’s programme. IAEA Bulletin 43, No. 3, pp. 12-15. |

| [12] | Bakr, W.F; Hamed, A.A (2009). Upgrading the Physical Protection System (PPS) to improve the Response to Radiological Emergencies involving Malevolent Action Journal of Physical Security Vol.3, pp. 9‐16. |

| [13] | ElBaradei, M. (IAEA Director General) (2003). Address at the International Conference on Security of Radioactive Sources, Vienna, pp.11–13. |

| [14] | IAEA (1999) INFCIRCL 225/ rev.4 Corrected, "The Physical Protection of Nuclear Materials and Nuclear Facilities, pp.1-9. |

| [15] | Sandia National Laboratory, SAND2007-5591(2007). Nuclear Power Plant Security Assessment Technical Manual, Albuquerque, pp 3-113. |

| [16] | US Department of Homeland Security. National Infrastructure Protection plan. Available online:http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/NIPP_Plan.pdf (accessed on 28 April, 2013). |

| [17] | Fischer, R.J and Green, G.(2004). Introduction to Security,7Th ed.; Elsevier: Burlington, MA,USA, pp. 2-25. |

| [18] | Golan, A.; Maasoumi, (2008). Information theoretic and entropy methods: An Overview. Economet. Rev.27, 317-328. |

| [19] | Hicks, M. J. Snell, M. S. Sandoval, J. S. and Potter, C. S. (1998).Cost and performance analysis of physical protection systems–a case study, in Proceedings 32nd Annual International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology, Alexandria, Virginia, pp. 79–84. |

| [20] | IAEA-TECDOC-1355(2003).Security of radioactive sources Interim guidance for comment, pp.1. |

| [21] | Gonalez, A.J. (2001), Security of Radioactive Sources. The Evolving New International Dimensions. IAEA Bulletin: 43, 4. |

| [22] | Chapman, L.D and Harlon, C.P (1985). EASI (Estimate of adversary sequence interruption on an IBM PC: SAND-85-1105; Sandia Labs: Albuquerque, NM, USA, pp. 1-65. |

| [23] | IAEA (2011) Nuclear Security Recommendations of Nuclear material and Nuclear facilities (INFCIRC/2Recomndas 225/Rev5) Nuclear Security Series No 13 pp1-50. |

3. Determine the protection effectiveness of an intrusion path:

3. Determine the protection effectiveness of an intrusion path:

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML