-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Science and Technology

p-ISSN: 2163-2669 e-ISSN: 2163-2677

2012; 2(6): 172-181

doi: 10.5923/j.scit.20120206.06

Technology Business Incubation as Strategy for SME Development: How Far, How Well in Nigeria?

Adelowo Caleb M. , Olaopa R. O. , Siyanbola W. O.

National Centre for Technology Management (Federal Ministry of Science and Technology) PMB 012, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Adelowo Caleb M. , National Centre for Technology Management (Federal Ministry of Science and Technology) PMB 012, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

SMEs form sizeable proportion of enterprises of most developed and rapidly developing countries because of their contribution to GDP, employment and socio-economic development. Given their limitations of size and resources, SMEs need special attention and assistance to survive and compete in the global market place. Technology Business Incubation (TBI) therefore becomes a constructive intervention process to establish a positive environment that can nurture technology-based SMEs for sustainable development. The success of TBI depends on how the incubators are designed and managed. This paper discusses some of the challenges facing TBIs in Nigeria followed by requisite policy measures to resolving them.

Keywords: TBIs, SMEs, Nigeria, incubatees, Programmes

Cite this paper: Adelowo Caleb M. , Olaopa R. O. , Siyanbola W. O. , "Technology Business Incubation as Strategy for SME Development: How Far, How Well in Nigeria?", Science and Technology, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 172-181. doi: 10.5923/j.scit.20120206.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) constitute a significant part of most economies and make valuable contributions to its growth through innovation and competition[1,2,3,4,5]. They are major, indeed disproportionate, employers of labour and deployers of capital. They do, however, suffer size related disadvantages in access to finance, especially long-term finance and in management, SMEs have only limited management time available for extramural activities. They cannot benefit from scale economies both from the output and input side. Small size is an important constraint for process and product innovations, which are the core of recent competitiveness[2]. Moreover, difficulties in gaining access to tangible and intangible resources, limited access to scientific knowledge, poor management skills, and lack of know-how hamper survival rates among (high tech) new ventures [6,7,8,9,10,11]. These drawbacks that are common to entrepreneurs and new ventures in most developed countries are exacerbated in developing countries due to additional impeding factors, such as lack of human capital, high macroeconomic volatility, and poor functioning formal institutions. Compensation for these disadvantages could level the playing field and enhance the commercial effectiveness of small enterprises. Many of them could also benefit from closer contact with relevant university departments and research institutions. Support programmes range from technical assistance to tax incentives, from direct supply of capital to regulatory provisions, training support to innovation and other types of incentives are important contribution to the survival of small firms in this keenly competitive and knowledge-based economy. Two of the mechanisms employed to nurture and provides these services to small firms for more than two decades are ‘business incubation’ and/or ‘technology parks’. Incubators provide an attractive framework to practitioners in dealing with the difficulties in the process of entrepreneurship summarized above. They can be considered as a remedy for the disadvantages that small and new firms encounter by providing numerous business support services and they are useful in fostering technological innovation and industrial renewal (6,7,12,13). They can be viewed as a mechanism (i) to support regional development through job creation[14,15,16,17], (ii) for new high tech venture creation, technological entrepreneurship, commercialization, and transfer of technology[15,18,19,20], (iii) an initiative to deal with market failures relating to knowledge and other inputs of innovative process[21]. Studies have shown that one third of new firms do not survive the third year and about 60 per cent do not survive the seventh year[22]. This number considerably falls to 15–20 per cent among incubator tenants[23,24,25,26]. For these reasons many countries have increasingly been engaged in establishing incubators.In general terms, tenant firms of technology incubators are start-ups or spin-off firms, which are established specifically to exploit technologies that are develop in the nearby tertiary institutions/research institutes or private laboratories. The proximity of the incubators to the knowledge sources enables the firms to have adequate interactions required to sustain the exploitation of the emerging technologies.

1.1. What then is Technology Business Incubations (TBIs)?

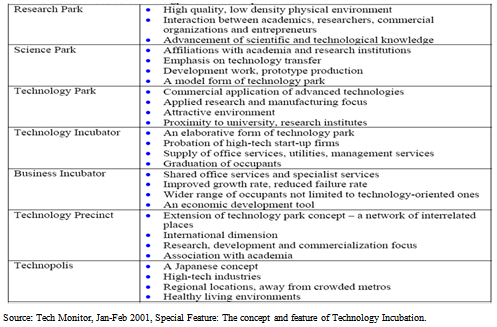

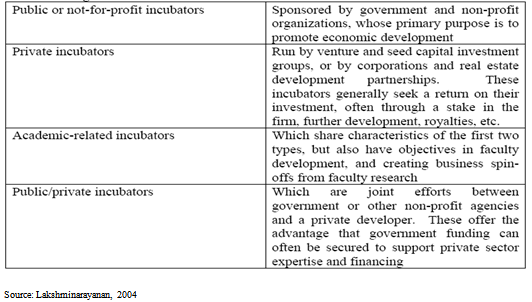

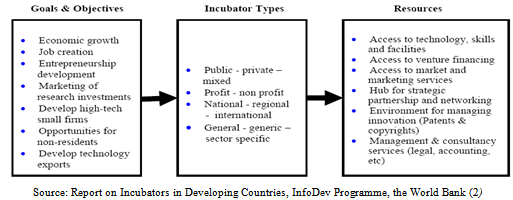

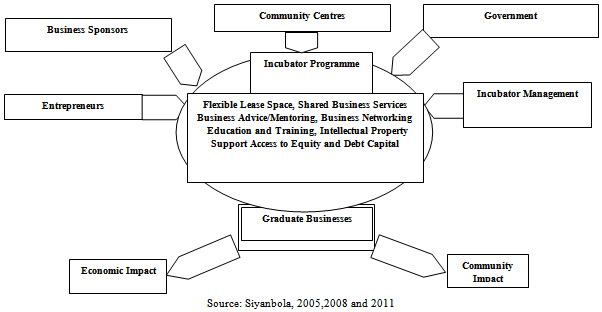

- There are several definitions and approaches to business and technology incubation. Conceptually ‘incubation’ is a more diligent and planned process than clustering or `co-location’ and therefore needs careful attention to the problems of prospective occupants, extending well beyond providing infrastructure and office services (27,41). According to the National Business Incubators Association (NBIA), “Business Incubation catalyses the process of starting and growing companies, providing entrepreneurs with the expertise, networks and tools they need to make their ventures successful. Incubation programmes diversify economies, commercialise technologies, create jobs and create wealth”. The technology incubators generally focus on nurturing technology intensive enterprises and knowledge-based ventures. The technology incubation system (TIs) is variously represented by entities such as Technopolis, Science Parks, Research Parks, Technology Parks, Technology and/or Business Incubators. These entities operate as separate organisations but are mostly integrated with other players in the innovation system. The terms Science Parks, Research Parks and Technology Parks as well as Technology Incubators (TIs), Technology Innovation Centres (TICs) and Technology Business Incubators (TBIs) are used interchangeably in many countries depending on the level and type of interaction between R&D community, venture funding and industry. In this paper the term business incubator will be taken to mean a controlled environment-physical or virtual- that cares, and helps new ventures at an early stage until they are able to be self-sustained through traditional means while TI will apply generically to all the organizational forms for promoting technology-oriented SMEs respectively. The attributes of various constituents of TIs are indicated (see Table 1 of the appendix).The organizational format of TIs also varies and could generally be categorized as public or not-for-profit incubators, private incubators, academic-related incubators and public/private incubators which are referred to as hybrid in most literatures (see table II).Also, TIs may thus have a wide range of goals and objectives giving rise to different forms of incubators specializing in accessing diverse resources as depicted in Figure 1(see Appendix).

1.2. Incubation Process

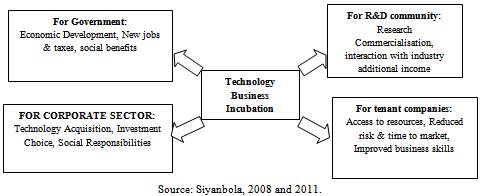

- The incubation process involves a number of stakeholders and operates in terms of a simple input-output model. The “inputs’’ mainly consist of the inputs made by stakeholders (e.g. provision of finance), management resources, and projects put forward by entrepreneurs; the middle process is known as the “Reactors’’ where various inputs are brought together in the business incubation process through the provision of incubator space and other services to companies while the “outputs’’ is the last process where successful companies graduate with positive job and wealth creation impacts on local economies (see figure II of the appendix). Incubation process, if properly followed, could lead to many benefits. In theory, TIs stimulate the innovation process by linking technology development to market demands, while providing capital for innovation, particularly in start-up enterprises that are deemed too risky for many investors[28,7]. They foster effective interactions among the elements of the National System of Innovation (NSI) and facilitate the commercialisation of research results as well as the acquisition and use of state-of-the-art technologies. Not only this, TIs promote the exploitation of domestic resources which equally lead to the improvement of international competitiveness of national industry. In summary, the benefits of TIs to respective stakeholders are synoptically presented figure III of the appendix.

2. Best Practices around the World

2.1. The United States

- In the year 2000, according to NBIA there were about 900 incubators of all types and models in the United States (Peters et al, 2004) (and as at 2009, it has increased to about 7,500 with almost half in Asian countries[29]). American incubators have had a lot of impacts on their economy over the past fifty (50) years. As per the NBIA estimates, since 1980 the North American incubators have generated 500,000 jobs and every 50 jobs created by an incubator has generated another 25 jobs in the community. Incubator graduates create jobs, revitalise neighbourhoods and commercialise new technologies, which strengthen local, regional and even national economies. The survival rates of the U.S. incubators graduates are in the average of 87% and it have also brought down the start-up cost by nearly 40-50 per cent. Similarly, OECD countries have also reported high survival rate ranging from 80-85 per cent as against 30-35% survival rates of non-incubators start-up firms[30]. Specifically the ‘Silicon Valley-Innovation machine’ has generated 7,000 electronics & software companies; 300,000 top scientists (1/3 born abroad) and many new firms and new millionaires are made almost every month. What makes Silicon Valley work is that there is critical mass of scientists, Technical infrastructure, venture Capital, Risk-taking culture, competition, ethnically diverse and world-class research universities[25]. These resources are very critical for the survival of incubator and the incubatees.

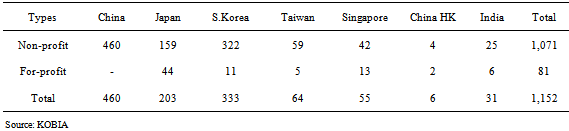

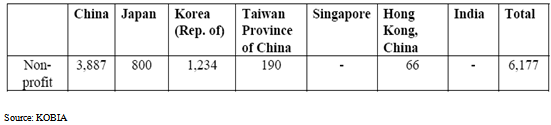

2.2. China

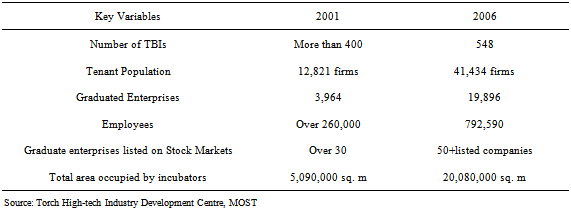

- According to Korean Business Incubation Association (KOBIA) there are over 1,500 incubators in some of the countries of the Asia Pacific region as at 2003 (Table 3). Japan has established nearly 200 incubators, the Republic of Korea has around 330 incubators and China is leading in the region with a figure of 460 while the number has increased to over 1,050 in 2009. India has also established more than 30 S&T entrepreneurs’ parks (STEPs) and TBIs apart from 35 software parks. Hong Kong, China, Singapore, Taiwan Province of China and Malaysia have also invested in technology incubators and parks with the major focus on ICT and biotechnology. In addition, countries such as Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand have also established few technology incubators and other developing countries in the Asia Pacific region have also shown keen interest in the TI programmes. Nearly 80% of the incubators in the region are TIs (see Table 3 in the appendix).The incubators in most of the developing countries are in the early stage of development and the majority of them are supported by the Federal and/or local governments. Some support has also been extended by multilateral and bilateral donor organisations. In some countries such as China, Malaysia, Republic of Korea and Singapore a few high-tech companies have now started investing in incubator programs to foster their R&D activities[31]. The details of incubator graduates (firms) in selected Asian countries are shown in Table 4 (appendix).China has been one of the early protagonists of TBIs. The technology incubation policies and programmes in China basically evolved from the `Torch’ programme initiated in 1988 by the State Council and is implemented by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST). The Torch programme is truly all-embracing. The core mission of the Torch Program is to give scope to the advantages and potentials of China’s scientific and technological forces and accelerate commercialization of high and new technology achievements, industrialization of high and new technology products and internationalization of the high and new technology industry with market as the orientation[32]. The focus of the Torch Program is to create an environment favourable for the development of high and new technology industry, which include such initiatives as formulation of related policies, laws and regulations, establishment of a suitable management and operation system for high-tech industry, exploration of new financing channels including venture capital investment mechanism, developing domestic and foreign information sources, building information networks and formulate long and mid-term development plans as well as implementation plans consistent with objective reality.The programme administration, in consultation with the MOST and other ministries formulate the policies, laws and regulations for the development of high-tech industries, establishes operational mechanisms for the development of high-tech industries, promotes financing sources and venture capital mechanisms, creates information and business networks and also prepares the medium and long term implementation plans. The national government is also supporting high-tech enterprises involved in the implementation of Torch Programme through preferential policies[33]. The Torch programme also implements specific projects for the development and commercialization of new technologies in specialized fields. Most of the high-tech incubators have been established by the administrations for Science and Technology Industrial Parks (STIPs) coordinated and administered by the Torch programme office. Priority areas include new materials, environmental technologies, biotechnology, and aerospace and information technology. Tenant companies are mostly spin offs from universities, R&D institutions, state owned enterprises but ownership typically remains with the parent institution. The Chinese SME Promotion Law has also been a positive development that has enabled the growth of SMEs in China.There are now other incubator types and forms being set up in China with the support from various sources such as government, universities, self-financing and also through public-private partnership. China has been proactive in formulating specific fiscal policies and incentives to encourage both the incubators and their tenants such as providing tax exemption, reduction of income tax, low rentals to attract talented entrepreneurs and start-up companies and also to facilitate international cooperation and financing mechanisms. Besides the national, local governments have also formulated policies and enacted laws for encouraging technological innovation, commercialization of R&D results and promotion of technology intensive SMEs which tacitly support the development of technology business incubation in China[34]. As a result, China is only next to USA in the number of operational TIs. This is the result of strong government back-up, proactive policies, programmes and extensive networking. In China the emphasis is increasingly on the development of technology based SMEs through TIs. At present China’s technology incubators are in a transitional phase from government-owned, non-profit institutions to mixed non-profit and profit ownership. In China, the first TBI formed in 1987 was modelled after best practices used in developed countries and adapted to specifically suit China’s unique business conditions. The objectives are to:i. offer hi-tech start-ups with optimal incubation servicesii. offer an environment for market exploitation and international cooperationiii. training founders of companies to become mature entrepreneursiv. form part of major measures to help develop China’s hi-tech industryChina’s TBIs strengths are as a result of: • Strong government investment (over $2billion) has enabled rapid expansion to 1,600 incubators • Introduction of International Business Incubators (1997) in China, and abroad in UK, USA, Russia, Singapore• Promoting cultural changes from ‘socialist’ to ‘market’• Now becoming vast Real Estate & virtual opportunities• The national development strategy- ‘Torch programme initiative’• Critical mass of scientist and technical infrastructure.The result of the effort of government of People’s Republic of China to develop a virile incubator through the Torch programme generated the result in table 5 of the appendix;In 2008, China earmarked US$3 billion for incubation development to:• Encourage entrepreneurship to bring out the unprecedented tide of technology innovation;• Perfect technology incubation system comparatively;• Become the new beginning, hot spot, brilliant spot for the implementation of indigenous innovation and the development of local economy;The Impacts of this action was that export earnings rose to US$1.5 billion; tenants applied for 17,225 patents over five years; more incubation expertise already being exported (at the invitation of UNDP, UNESCAP and UNESCO); over 200 incubation managers trained; good infrastructure (real estate, information network and venture capital).

2.3. Israel’s Technology Incubator Programme

- Nationwide technology incubator programme was launched in 1991 to utilize the S&T potential of immigrants from the Soviet Union. This was a well-conceived idea to generate employment for the Israelis who returned home after the war and paved way for the development of the economy. Over the years, there have been over 26 technology incubators in Israel which support fledgling entrepreneurs and opportunity to develop the innovative technological ideas and set up new businesses in order to commercialize them. The incubation, having taken the advantage of the infrastructure, venture funds, critical mass of scientists and skilful managers, has generated more than 250 technological projects which were carried out in the i incubators and as at the end of 2006, over 1000 projects had matured and left the incubators while over 51% of the graduates are still in business and have 1,400 employees. The total private investment obtained by the tenant companies is more than 1.5 Billion Dollars of which technology incubators have become massive repositories of potential ideas for new high-tech ventures in the future.The general characteristics peculiar to TBIs in Israel are that: • Tenant firms of Technology Incubators are start-ups or spin-off firms, which are established specifically to Exploit Technologies that are developed most often in the nearby Tertiary Institutions, Research Institutes or Private Laboratories; and• The proximity of the incubators to the knowledge sources enables the firms to have adequate interactions required to sustain the exploitation of the emerging technologies. The success factors include proper selection and monitoring; access to capital; on-site business expertise and milestones with clear policies and procedures particularly the necessary Infrastructure[35].

2.4. Nigerian Case

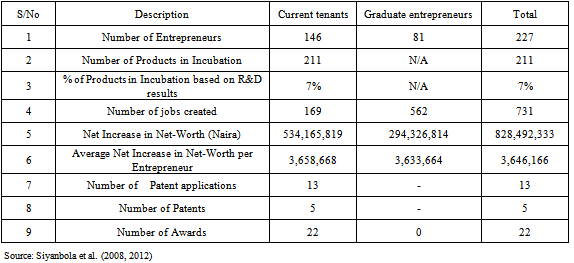

- The concept of Technology Incubation was introduced to the Nigerian Government by UNDP & UNFSTD in 1988. The Federal Government then commissioned a consortium of 3 firms to advise on the desirability and implementation modality (those 3 firms are NISER, OAU and a private consulting outfit). Eventually, the first TBI in Nigeria was established in Agege in 1993, followed by the ones in Kano and Aba in 1994 and 1996, respectively[36, 38,39]. The choice of these 3 cities was informed by the fact that they are industrial nerve centres in the regions where they are located. These centres were established by the Federal Government to be managed by the Federal Ministry of Science and Technology (FMST) and since then, 12 additional centres have been established across the country. As at 2009, the figure has increased to 25 centres. The objectives of TBIs in Nigeria are;• To boost the industrial base of the country through commercialisation of R&D results, upgrade and enhance the application of indigenous technologies;• To nurture the start-up and growth of new innovative business engaged in value-added and low, medium and high-technology-related activities over a period of time; and• To promote functional linkage between Research and Industry.Adegbite, 2002 summarized the benefits of TBIs in Nigeria as follow; Promotion of indigenous industrial development; Innovation and commercialisation of R&D results from Research institutes and knowledge centres; Economic diversification through the development of SMEs in manufacturing and services; Linkage of SMEs with big businesses by acting as local suppliers thus reducing dependence on imports; and Job creation by new SMEs to reduce unemployment.With these objectives and expected benefits in mind, the country has not gained much from the operation of incubation for a period of seventeen years (1993-2010) as the meagre achievement of the programme is as shown in the table 6; While China and Israel are making significant progress in their respective incubation programmes, Nigeria seems not to be faring well both in terms of impact and growth in incubation. One of the key objectives is to commercialise R&D results while only 7% of the products emanating from our incubation centres (of the 17centres surveyed) can be traced to the research system. It is apparent that there is no proper focus on the objectives and administration of the incubation centres. Also, from policy perspective, China introduced Torch program to speed-up the development of SMEs through their incubation system and this is a good model that Nigeria can emulate.

3. Making TBIs work in Nigeria

- It has been argued by scholars that the primary goal of TBIs in developing countries is to facilitate economic development by improving the entrepreneurial and technological base through supporting technology-oriented SMEs[36,37,38]. Consequently the TBIs present specific features and challenges, which are largely influenced by the local societal, cultural, economic and financial environments. The assessment methodologies of TBIs also tend to differ considerably from the developed economies as the priorities and goals are different. The existing approach for evaluating the performance of TBIs in developed countries essentially focuses on survival rate and jobs created. They also inculcate the entrepreneurship culture in others and bring about wider technological, social and attitudinal changes in the society, which create a multiplier effect[36]. The learning process associated with the incubation process itself is a valuable intangible national asset in strengthening the National Innovation System. Most TBIs programmes however give priority to the material dimension or the physical infrastructure whereas the emphasis should be on value added services. Much still needs to be done in improving the overall performance of TBIs especially in developing countries towards risk minimization, enhancing the operational capabilities and business support services. The broader objectives of incubation must address local and regional economic development; encourageentrepreneurship and employment generation achieved through promotion of innovation in both traditional sectors and emerging fields such as Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and Biotechnology. The survival and success rates could be improved by adopting best practices and strengthening public-private partnership. In this context, strengthening strategic partnership and networking would enhance the capabilities of TIs in rendering quality services to the venture enterprises during the incubation as well as after incubation.

4. Policy Options for Enhancing and Strengthening Technology Incubation in Nigeria

- The review of the global best practices has shown that the programmes of Technology Incubation in Nigeria have not lived up to the expectations for which it was conceived. Many areas of its operation and management are a great departure from the global standard practice and this is responsible for its failure to properly achieve the aim for which it was created to achieve. However, the programme can still be repositioned and re-invigorated with a view to making it more relevant to the developmental needs of the country and at the same time conform to the global best practices.Thus, some of the policy options for furthering the best practice of TBIs in the Nigeria based on the lessons learnt from the selected countries are as follows:(i) Intensifying S&T and R&D initiatives towards strengthening the national innovation system. The proportion of R&D expenditure to GNP in most developing African countries is low. R&D is also constrained by the lack of a critical mass of R&D personnel in many developing countries to innovate and produce new technology. In order to achieve this, there is the need to re-examine the concept of Technology Incubation so as to ensure that the programme is focused on technology value added products and services. In doing this, emphasis should be placed on development of R&D results and their commercialization, development of indigenous technologies, drive start-up rates for technological oriented enterprises, promote indigenous technology clusters, and commercialize the technologies from research institutes and higher institutions of learning [37,41].(ii) Restructuring the financial systems to provide appropriate and alternate types of financing to promote technology intensive SMEs. The venture capital industry is yet to play an active role in the promotion of technology based ventures especially in traditional sectors. This needs to be established to directly provide funds to tenants on a revolving basis as suggested in NCST, 2005 that Federal Government Technology Fund be established and administered by the National Technology Incubation Board to facilitate the funding of the TBI Centres which should be modelled along the Small Business Technology Transfer Programme (STTR) and the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Programme of USA[37].The process of restructuring should also be extended to the operations, management and supervision of TBIs for effective services delivery. To this end, the newly established National Technology Incubation Board should be empowered to provide central coordination, policy formulation; development of operational guidelines; appointment of staff; funding; establishment of new TBIs; and facilitation of development of relocation Centres[37](iii) Creating knowledge enabling industries particularly in the area of ICT and biotechnology. Advancement in ICT will accelerate capital flows into the traditional sectors. Formulating technology and innovation management programmes to accelerate participation of start-ups and SMEs in technology intensive activities.(iv) Accelerating the development of critical infrastructure and importance of e- activities. For instance, for any new incubation centre to operate, certain basic infrastructure should be put in place for effective delivery. The value added of incubator operations lies increasingly in the type of business support services provided to clients and developing this aspect of incubator operations should be a key priority [37,39,41]. There is a widespread acceptance that although the provision of physical space is central to technology incubation concept, it is the quality and range of business support services that should be the main focus. There are four key areas that merit special attention: entrepreneur training, business advice, financial support and technology support[37,40]. In Nigeria, The National Office for Technology Acquisition and Promotion (NOTAP) provides technology support services which could assist TBIs in the development and commercialization of projects. Such support services include patent services; access to patent information in the public domain; technical support in the commercialisation process; and technology advisoryservices.(v) Enhancing public-private partnership (PPP) for establishing and managing TBIs. It has been argued that public authorities have an important catalytic and leadership function and should provide the necessarily guidelines for the establishment and running of technology incubators[37]. The newly established National Technology Incubation Board should issue guidelines and other conditions for the establishment and operation of technology incubators and coordinate their activities to encourage PPP.(vi) The establishment and strengthening of networking among the stakeholders in Nigeria as well as in the African region will assist in improving the quality of services. Strong formal linkages with knowledge institutions both within and outside Nigeria should be encouraged. TBIs should not only be integrated into the local infrastructure but also to national and global sources of technologies and markets[37]. It has also been suggested that an association of Nigerian Technology Incubators, to be facilitated by the National Technology Incubation Board, should be formed to facilitate their interaction.(vii) The international agencies could facilitate technical capacity building among TBIs and also promote technological partnerships at the firm and institutional level. They can also disseminate lessons learnt in promoting technology incubation in selected countries of the region.(viii) From the experience, the existence of formal admission and exit criteria is a defining characteristic of technology incubators and important in ensuring turnover of tenant companies. Therefore, the guidelines on admissions, monitoring and exit should be devoid of any ambiguity. Potential tenants should be required to complete an application document that must include information on specific project proposals, scope, envisaged period of incubation, commercial and technical feasibility of the project, and new technology content while the period of incubation should be limited to a maximum of five (5) years[37].Support services, however small, should be made continuous for graduated firms especially in the provision of loans, counselling and monitoring services.In addition, as a matter of policy, emulate those good global practices in TBIs as deciphered by pursuing:• Clearly defined Objectives and Mission• Strong Advocacy for Government Commitment• Requisite technology transfer policy or intellectual property policy• Recruitment of Entrepreneurial Managers• Selection of Tenants according to “needs and fits “• Tailoring and Leveraging on existing services• Building on local and international linkages• Diversification of sources of finance• Venture capital, Business Angel, etc• Sharing of experience through networking* Performance Evaluation Mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

- From our argument up to this point, it is very clear that understanding the best way to manage innovation is a key element in shaping the competitiveness and economic growth in the emerging knowledge-economy and that the ability of SMEs to participate in and benefit from the knowledge economy is dependent on the extent of linkage with System of Innovation (NSI) in any country. Therefore, developing countries have to evolve their own strategies, policy options and mechanisms for establishing TBIs. There is the need for strengthening of networking among Incubators in order to promote knowledge sharing of best practices; and countries should maximize those factors that gave them both the comparative and competitive advantages. With all efforts directed at the attainment of all these, it is our conviction that the best practice of technology incubation required for the promotion of regional economy through job creation and wealth generation will be achieved.

Appendix I

| Figure 1. Goals, Types and Resource endowments of TI |

| Figure 2. Incubation Process |

| Figure 3. Benefits of TBIs to Stakeholders |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML