Orville Ashley1, Steve Simske2

1Colorado State University, Systems Engineering Department, Fort Collins, Colorado

2Colorado State University, Professor of Systems Engineering, Systems Engineering Department, Fort Collins, Colorado

Correspondence to: Orville Ashley, Colorado State University, Systems Engineering Department, Fort Collins, Colorado.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Gun violence remains prevalent due to a lack of policy, governance, and technological solutions needed to combat it. Devastating news related to gun usage is ubiquitous, including unauthorized usage, unwanted injuries, accidental deaths, and suicides. It is becoming increasingly more difficult to manage firearm issuers due to limited efforts received from gun legislators and the National Rifle Association. The need for the application of systems engineering (SE) to firearm usage is evident to limit and reduce these types of incidents; in effect, to incorporate SE solutions to offset missing policies and governance in society. The proposed approach focuses on developing a systems engineering based firearm model to help manage the operation of different types of firearms. To better manage these types of incidents, the author used a simulation model and collected pertinent datasets to show the implications and to suggest the methodology used to derive desired results. The evaluation of the proposed approach shows its ability to handle unwanted operations more efficiently with a designed performance rating of 95 percent. The authors describe a proposed test and analysis method that can offer a more accurate and conservative estimate of SE firearm performance during authorized and unauthorized events, resulting in a safer design intended to reduce self-inflicting outcomes.

Keywords:

System, Verification, Analysis

Cite this paper: Orville Ashley, Steve Simske, Applying Systems Engineering to Mitigate Unwanted Firearm Incidents, Journal of Safety Engineering, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2025, pp. 1-13. doi: 10.5923/j.safety.20251301.01.

1. Introduction

Intentional self-harm (suicide) is a growing problem in the United States (U.S.) and has recently become one of the top ten leading causes of death [1]. Studies have shown that higher rates of firearm ownership correlate with higher rates of firearm suicide. [8] This study is designed to investigate several factors that potentially lead to self-infliction by firearm (including suicide), accidental firings, and assaults that occur by gunshot wounds.According to recent data (from 2017), a total of 39,773 deaths were due to firearms, a number increasing over the previous year. A full 60% of these firearm deaths were self-inflicted. The firearm deaths due to assault accounted for 36.6% of these nearly 40,000 deaths [1]. Though a majority of firearm deaths were self-inflicted, the amount of research and data on self-inflicted firearm deaths and injury is not yet comprehensive. This 2017 study also indicates that not all gunshot wounds are intentionally self-inflicted; that is, intentional suicide. The discussions around self-inflicted gunshot wounds are interpreted as gunshot wounds for a given instant while the gun is in possession of the injured person at the time of firing with an unknown intent of the shooter. On the contrary, an assault by gunshot wound is defined as a moment when the firearm was not in the possession of the injured person at the time of firing [1]. Also, for the purpose of this study, accidental firing is defined as an act of the shooter firing without any awareness that the firearm is loaded, and the trigger operable when pulled. The objective of this study is to examine various scenarios of potential incidents that are inevitable when firearms are not equipped with preventative devices to mitigate the risk of suicide (ROS), accidental firings (AF), and assault by gunshot wounds (AGW). An in-depth application of systems engineering (SE) principles is used in conjunction with a test model platform engineered and built by the authors to test and verify variables against three possible common paths, namely, self-inflictions, accidental firings, and assault by gunshot wounds. The derivative of this systems engineering based concept and study uses SE principles and suitable data logic with communicable devices, making it possible to prevent and reduce firearm incidents significantly. The inputs are tested, verified, and validated against three commonly known inputs. Special emphasis on SE implications studied provides meaningful insights and implications and are offered as a viable path to mitigate the risk of self-inflictions, accidental firings, and assault by gunshot wounds. The known input under investigation includes 1) Potential angular movements of the firearm pointing toward shooter within the x-axis. For this scenario, the shooter would be pointing full arm length from self, whereby the chest region would be the horizontal reference to form a 90-degree angle with the direction of the firearm muzzle. All other angles are tested, verified and validated as subjects for strong potentials that can create self-inflictions and accidental firings. 2) Potential angular movements of the firearm pointing bi-directionally; sometimes upward, and at other times, downward within the y-axis for moments when the muzzle points away and toward the shooter. All known inputs are investigated with the use of artificial intelligence to appropriately test each segment described independently of each axis and as combined sets of input, to collect, verify, analyze and validate statistical data for outputs derived.Additionally, this study will also use sensitivity analysis to compare the effects of varying inputs through a combination of inputs previously described and to produce the potential outcomes and implications presented for each test segment.

2. Literature Review

Advancement of gun safety technology is developing at a very staggering rate. Technological approaches have emerged relatively passively with devices like trigger locks, magnetic encoding, touch memory, radio frequency and biometric trigger locks. Trigger locking devices are not all good, as the bar that connects the two sides of the lock comes far too close to the trigger, and the trigger can easily be hit while the lock is being put on or removed [2]. In addition, dropping or jostling the gun or even just applying too much pressure while the gun lock is on the gun can result in an accidental discharge [2]. Magnetic coding has its own pitfalls too, as it uses a magnet on a ring to physically move a lever on the grip of the gun. Essentially, this works when the decoder embedded in the custom grip receives signal from the magnetic encoder and responds by allowing the authorized user to fire the gun. The disadvantage is the user can still potentially use this technology for suicidal shooting. The implications are clear, as this technology does not have an angular restriction device embedded within the system as depicted by the proposed systems engineered firearm described later in this research. Biometric trigger locks, otherwise called IDENTILOCK, was introduced in 2017 and offered firearm users, civilian and law enforcement, a trigger locking system that blended speed, usability and practicality with all the safety and security for peace of mind [3]. On the contrary, the biometric trigger locks does not reduce unintentional firings and worse yet, does not deter authorized users from self-inflictions. The analysis of gun safety technologies offers some foundational insights, but they still exhibit some limitations with reference to suicidal shootings. Gun safety technology have continued to fail to have inclusive technological embedded devices in firearms to deter suicides and accidental firings at undesirable firing angles, and subsequently, unwanted trigger operations continue exponentially with horrific outcomes. In 2023, 58% of all gun related deaths in the U.S. were suicides (27,300) out of 49,316, or 55% - also involved a gun [4]. Thus, more than half of all suicides in 2023 involved a gun. That was one of the highest percentages since 2000, when 57% of suicides involved a firearm [4].It is evident that with the advancement of gun safety technology there exist a growing deficiency that resonates among them all – the inability of authorized users to deter suicidal shooting. This area of technology is the primary or focal feature the authors promote and have invested time to research the feasibility to better manage how guns should be restricted from suicidal and accidental discharges at angles pointing toward and away from users. The authors also believe that with strong advocates from legislative bodies, supported by the availability of well-equipped manufacturing resources, a systems engineered firearm is the solution needed to deter unwanted angular discharge and suicidal shootings.

3. Results

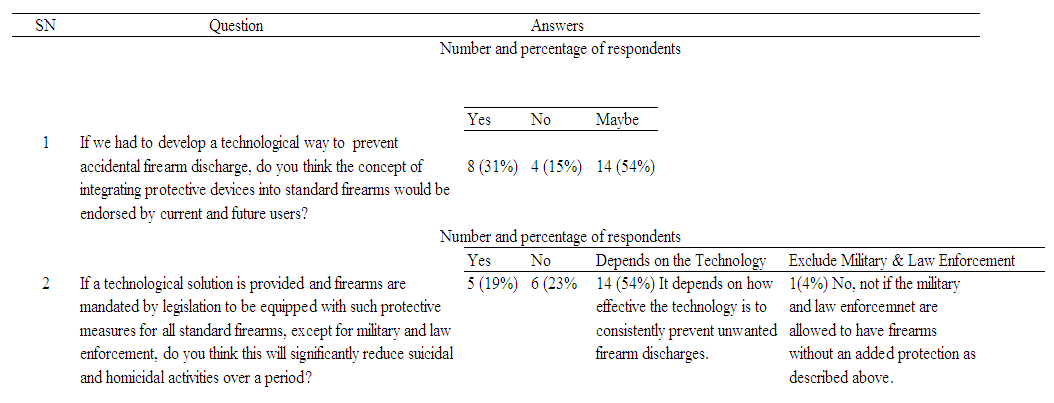

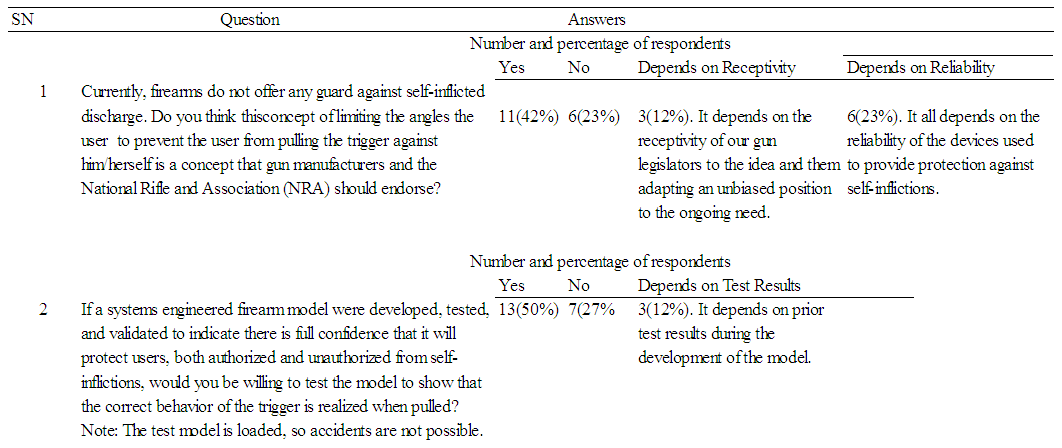

| Table 1. Mindset trends of some people in the USA regarding guns having protective devices |

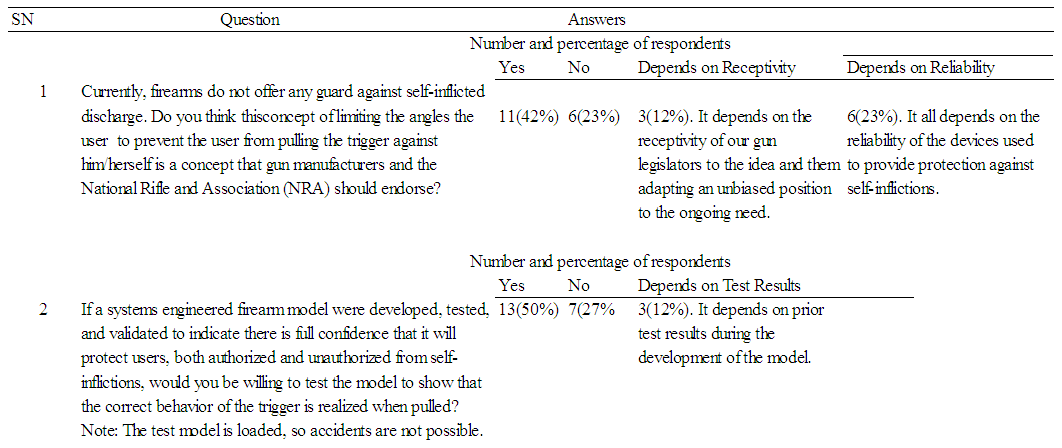

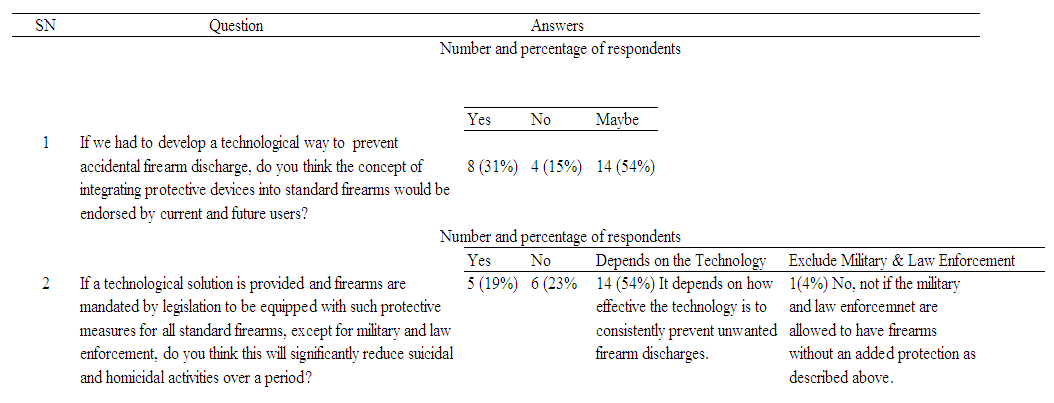

2 questions were asked of respondents from an online volunteered survey to capture some sense of what people in the USA think if guns have protective devices. The results are illustrated accordingly. | Table 2. Mindset trends of some people in the USA regarding restricting some angular directions on guns and their interest to test a developed model |

2 questions were asked of respondents from an online volunteered survey to capture some sense of what people in the USA think if guns had an angular restrictive device to protect users. The results are illustrated accordingly.

4. Discussion

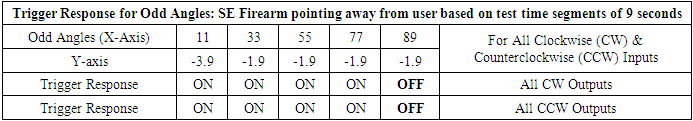

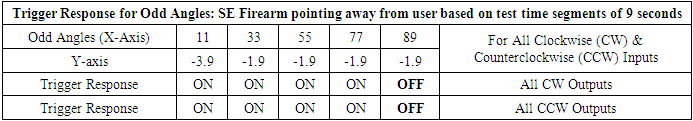

From Table 3, 10 tests were performed where the behavior of the output (green LED Bulb) spontaneously glow green for odd (horizontal) angles of 11, 33, 55, and 77 degrees (for both clockwise and counterclockwise directions) and at corresponding vertical angles of -3.9, -1.9,-1.9, and -1.9 (where a negative sign suggest firearm muzzle pointing downward vertically) degrees respectively. When horizontal angles are detected between 11 and 77 degrees and within the vertical angular constraints of -3.9 to -1.9 degrees, the trigger is operable and the green LED bulb turned on instantly for those specific instances of allowable inputs. Conversely, for an 89 degree test run, at a corresponding -1.9 degrees in the y-axis, the green LED bulb remained off which is exactly the response needed for an unsafe trigger operation. From Table 1, it is obvious that the mindset of the respondents answers to the online survey are more inclined to support the concept of developing protective devices, as 31 % said yes, and 54% said maybe. The second question has a more affirmative answer as the nature of the question offers a better sense of confidence and authority, and subsequently a resounding 54% said it depends on how effective the technology is. The SE firearm test model is engineered similarly with angular sensors to detect unsafe angles in excess of 88 degrees. Table 3. Trigger Response for odd angles along the x-axis in conjunction with angular y-inputs between -3.9 degrees and -1.9 degrees when SE Firearm test model points away from user

|

| |

|

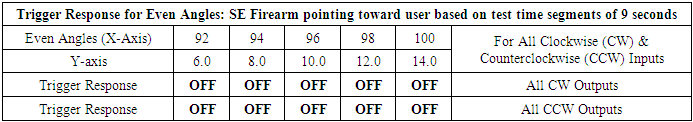

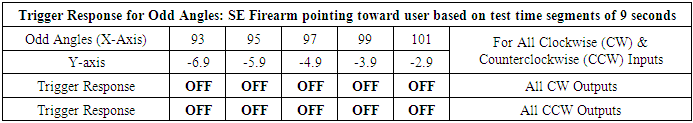

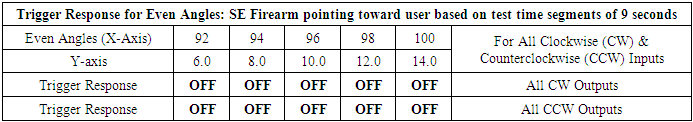

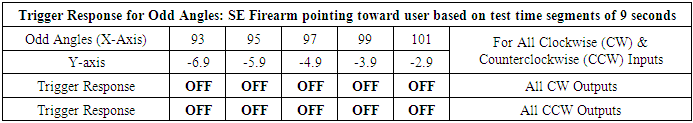

From Tables 3a and 3b, a total of 20 tests were performed at horizontal angles greater than 90 degrees to evaluate the behavior of the output (green LED Bulb) for even angles of 92, 94, 96, 98, and 100 degrees and odd angles of 93, 95, 97, 99 and 101 degrees (for clockwise and counterclockwise directions) at corresponding vertical angle sets of 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 degrees and -6.9, -5.9, -4.9, -3.9, and -2.9 degrees respectively. The results of all 20 tests were consistent with the designed intent of the SE firearm test model, that is, the trigger remained inoperable for angles greater than +/-88 degrees (where + and – signifies angular movements within the horizontal plane to the right and left respectively) in the horizontal plane and greater than +/-4 degrees (where + and - signifies angular movements within the vertical plane upward and downward respectively) in the vertical plane and occurring in combination for both x and y coordinates. From Table 2, it is obvious again that the mindset of the respondent’s answers to questions 1 and 2 is quite consistent with their previous answers provided in Table 1. The significance of their reply could be inferred to mean they understand there is a dire need for protective devices in firearms, and subsequently, they are more inclined and confident to support the concept of having protective devices that would limit unsafe angles and reduce suicidal rates to the extent that they are willing to test it. An affirmative interest was well received in this online survey which allowed responders in the USA and beyond to share their opinion and or convictions on this very important issue.Table 3a. Trigger Response for even angles along the x-axis in conjunction with angular y-inputs between 6 degrees and 14 degrees when SE Firearm test model points toward user

|

| |

|

Table 3b. Trigger Response for odd angles along the x-axis in conjunction with angular y-inputs between -6.9 degrees and -2.9 degrees when SE Firearm test model points toward user

|

| |

|

5. Verification and Validation

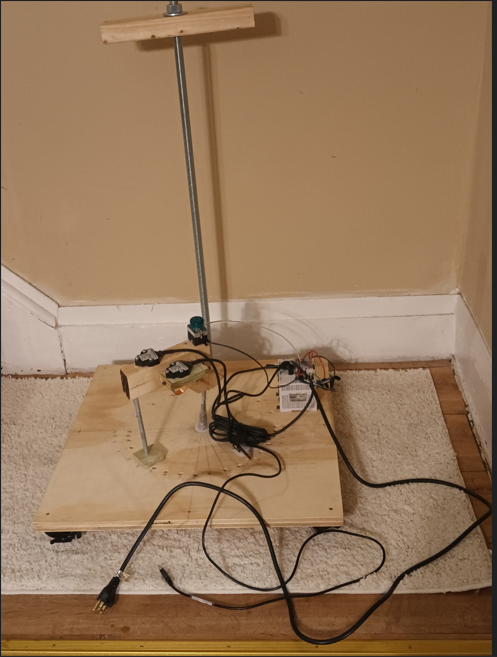

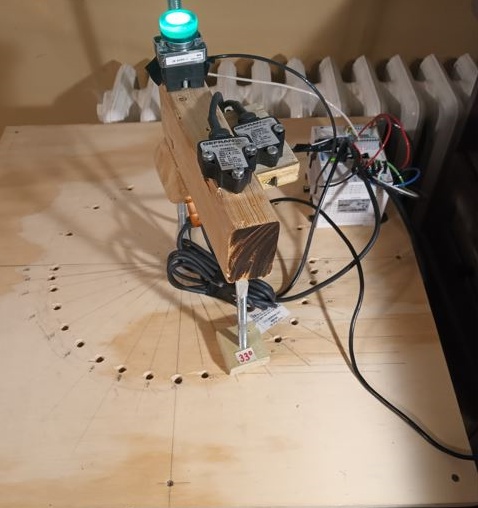

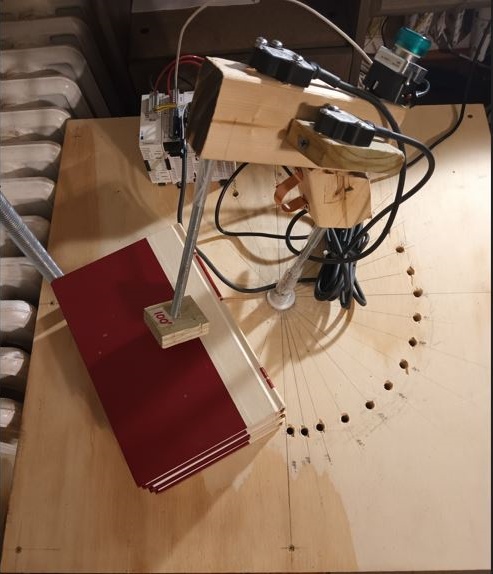

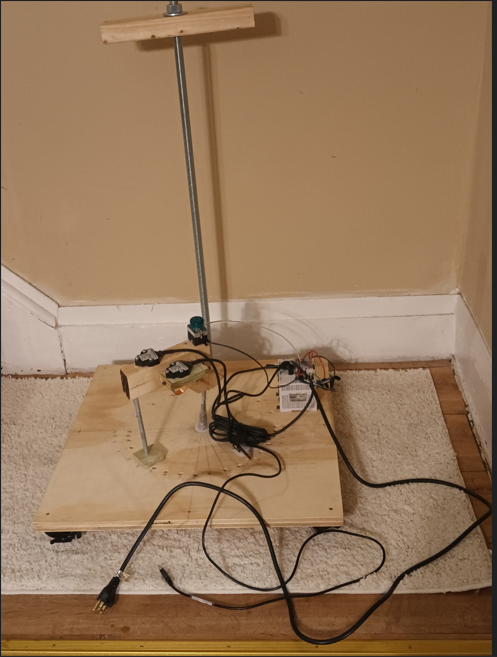

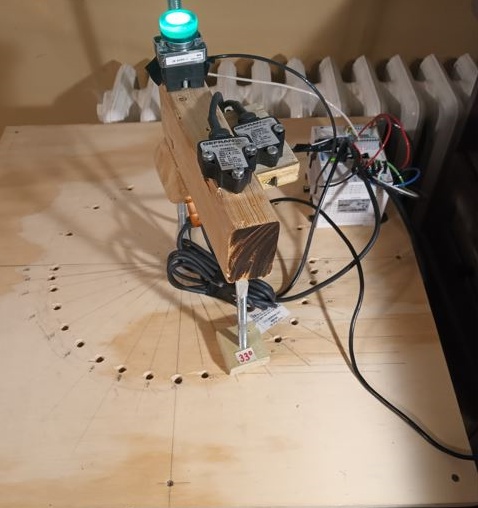

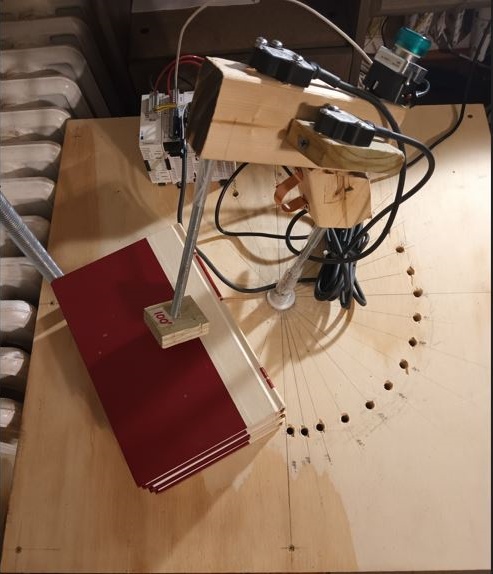

The system elements used in conjunction with this SE firearm model demonstrated clearly and satisfactorily the design intent of the trigger to operate when pulled or remain disabled. The net effect of such outcomes is highly predicated upon the inclusion of the right elements to build an architectural platform that produces a component level to a systems level to achieve the right solution to the problem at hand. An in-depth examination of the variables is considered with applicable supportive subsystems to ensure they would work correctly based on the SE firearm test model, as shown in Figure 1.  | Figure 1. Shows the fully developed systems engineered firearm test model |

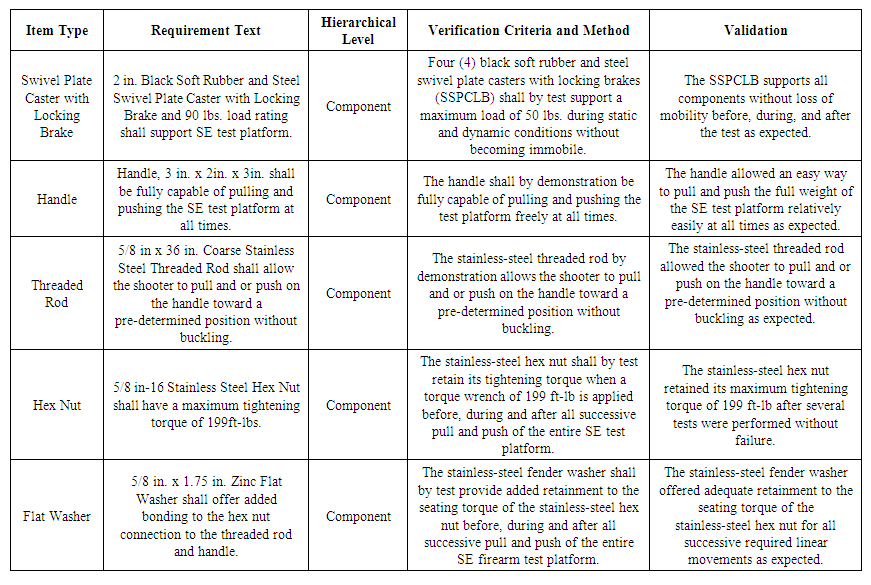

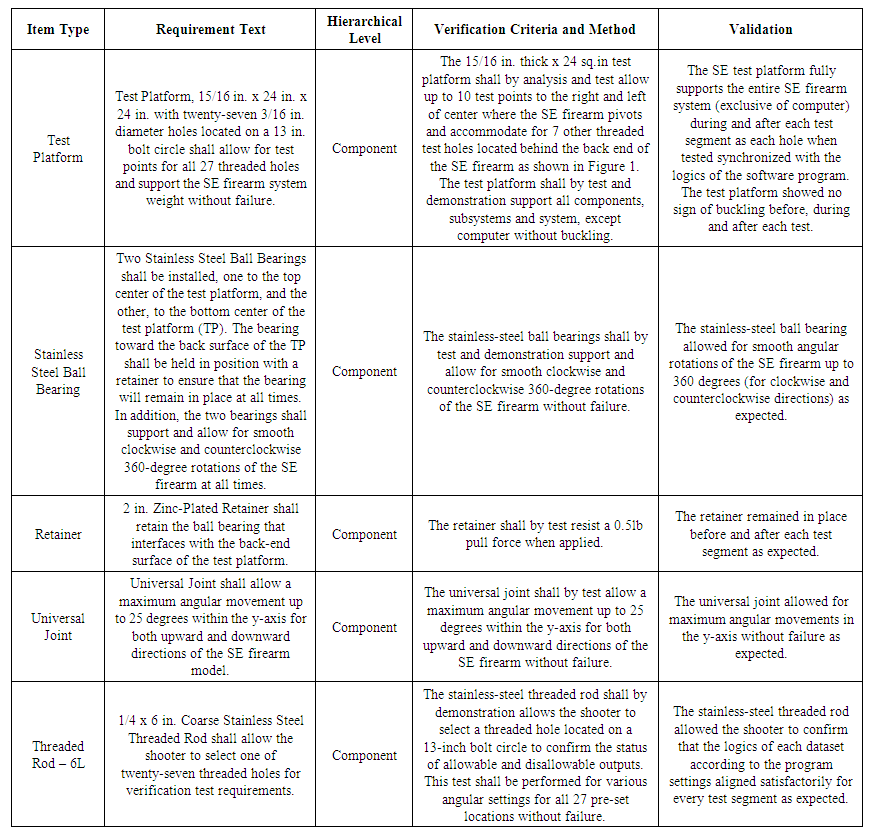

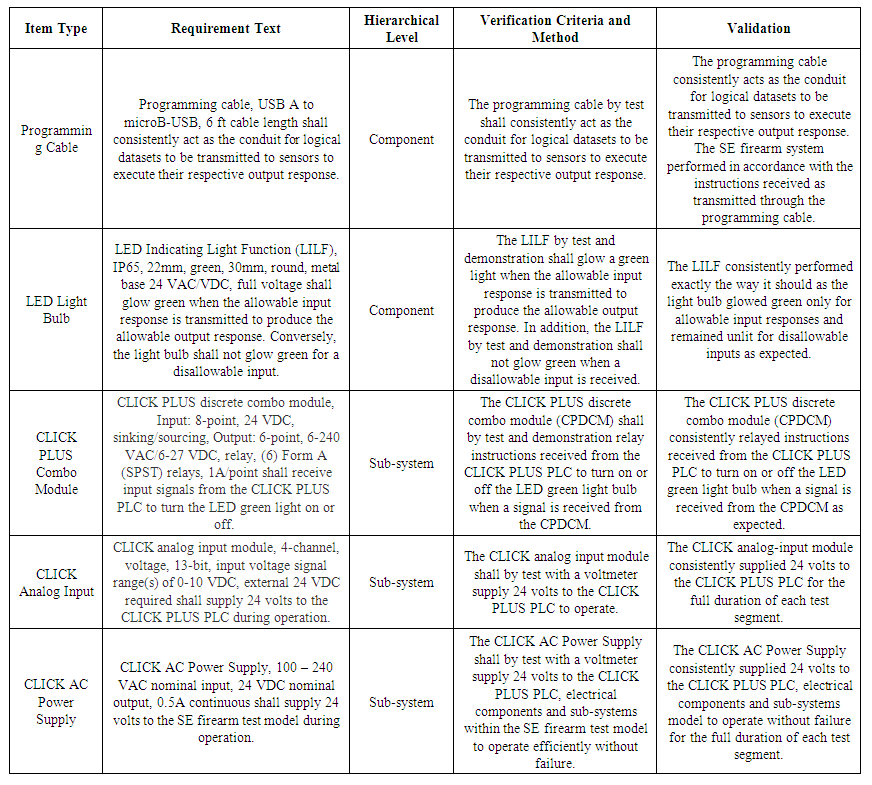

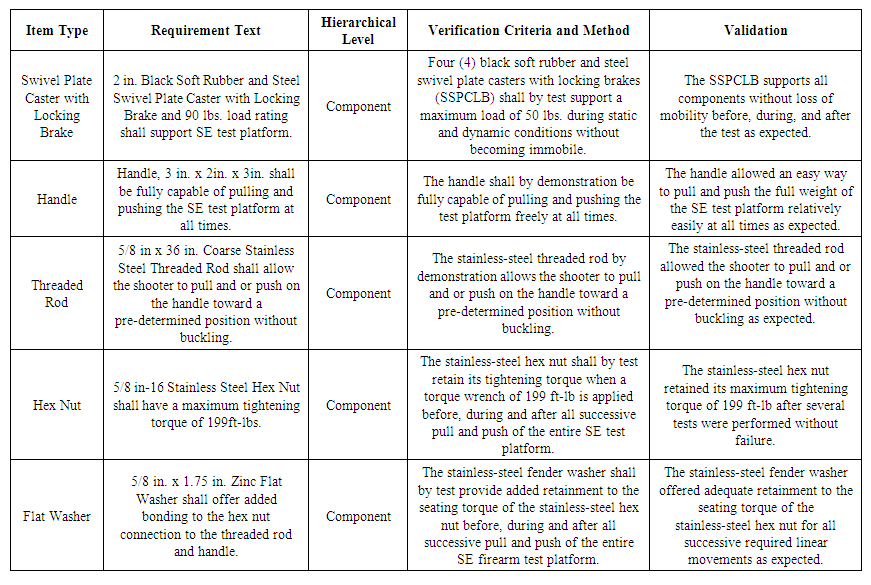

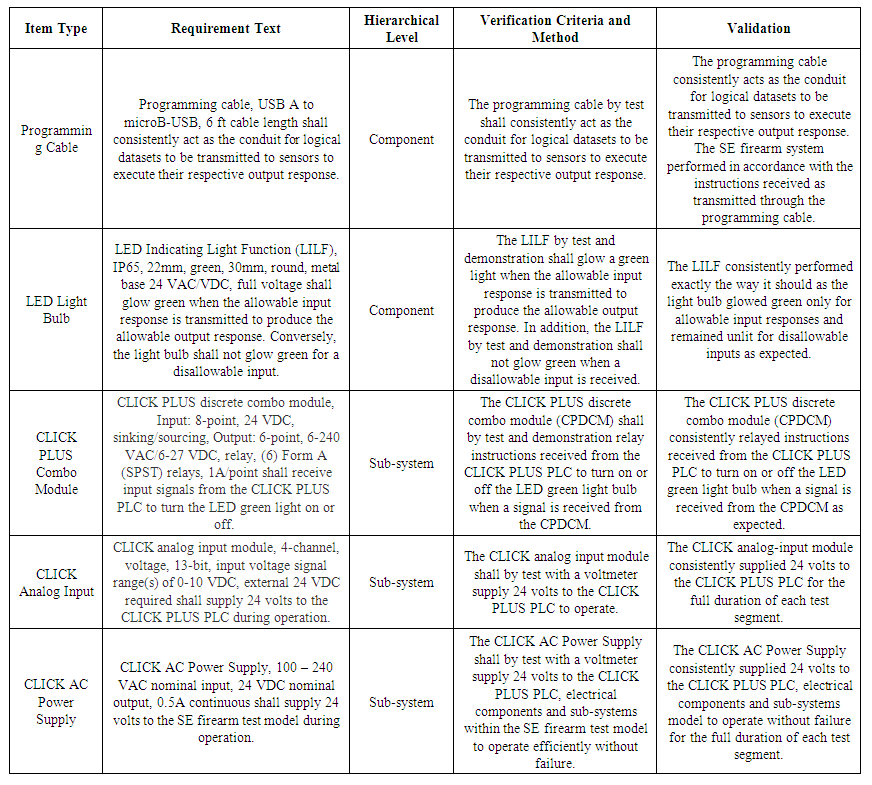

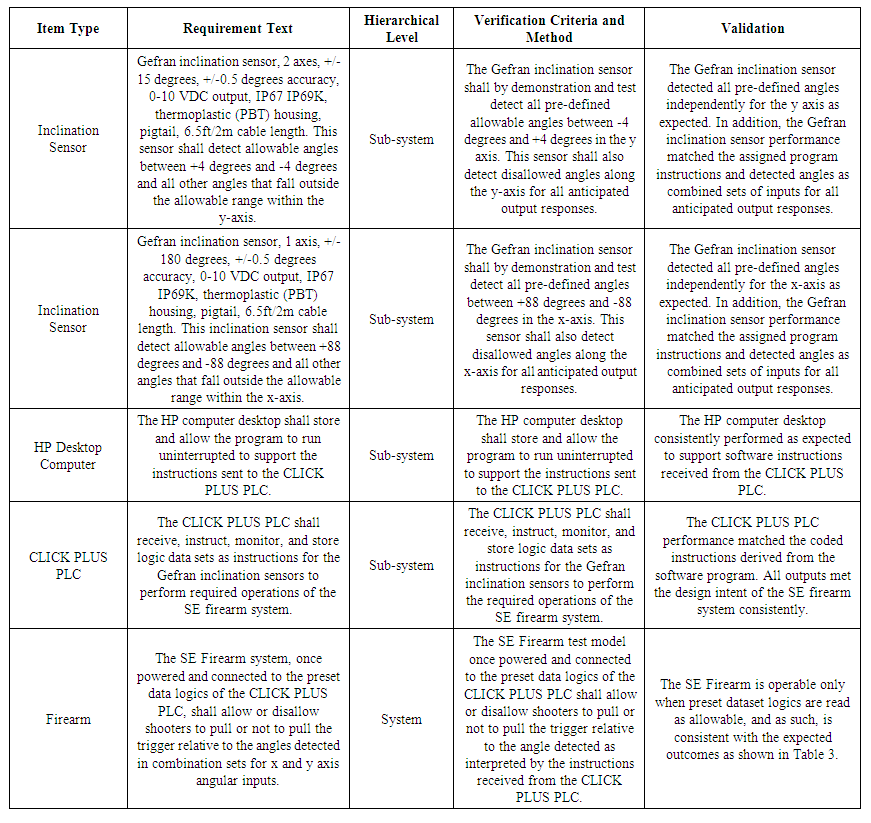

The verification process involves several components to support the designed intent for the outputs. For instance, when an allowable angle from reference is detected by the inclination sensor an electronic code is relayed to the Click Plus PLC as acceptable, and the SE Firearm system responds in accordance with the coded instruction received with a green light. Based on successful interactions of the model’s performance at this stage, verification is realized on the basis that the input received by the authorized user is confirmed by way of the coded instructions used by the user to initiate the validation of the input received to allow or disallow the trigger to operate during the test. The verification activities successfully cascade and become used in accordance with the instructions received by the Click Plus PLC in alignment with the performance expected at this final phase. This desired output is the culmination of the output performance expected that confirms the validation of the SE firearm anticipated behavior. A table of all components and subsystems was carefully inputted, designed, and built in accordance with their technological capabilities to produce the SE firearm systems model. Tables 4, 4a, 5 and 5a list all items used to produce desired test results with their corresponding hierarchical levels from component level to systems level.  | Table 4. Table lists and describes the SE firearm model mechanical components at varying hierarchical levels with their respective requirements, verification criteria and methods, and validations |

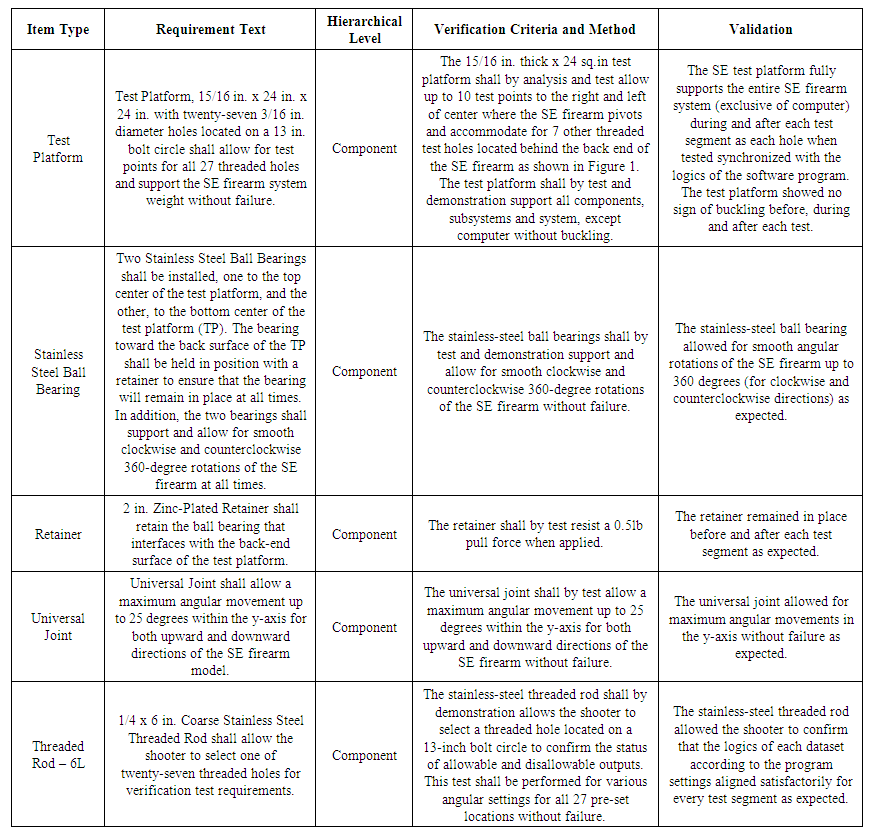

| Table 4a. Table lists and describes the SE firearm model mechanical components at varying hierarchical levels with their respective requirements, verification criteria and methods, and validations |

| Table 5. Table lists and describes the SE firearm model electrical components at varying hierarchical levels with their respective requirements, verification criteria and methods, and validations |

| Table 5a. Table lists and describes the SE firearm model electrical components at varying hierarchical levels with their respective requirements, verification criteria and methods, and validations |

6. Systems Engineering Methods

The systems engineering methods for the SE firearm are predicated on a systematic application of the scientific method to the engineering of a complex firearm system. The method used is typical of a SE method consisting of four basic activities applied successively:ο Requirements analysis.ο Functional definition.ο Performance requirements.ο Sensitivity analysis.

6.1. Requirement Analysis

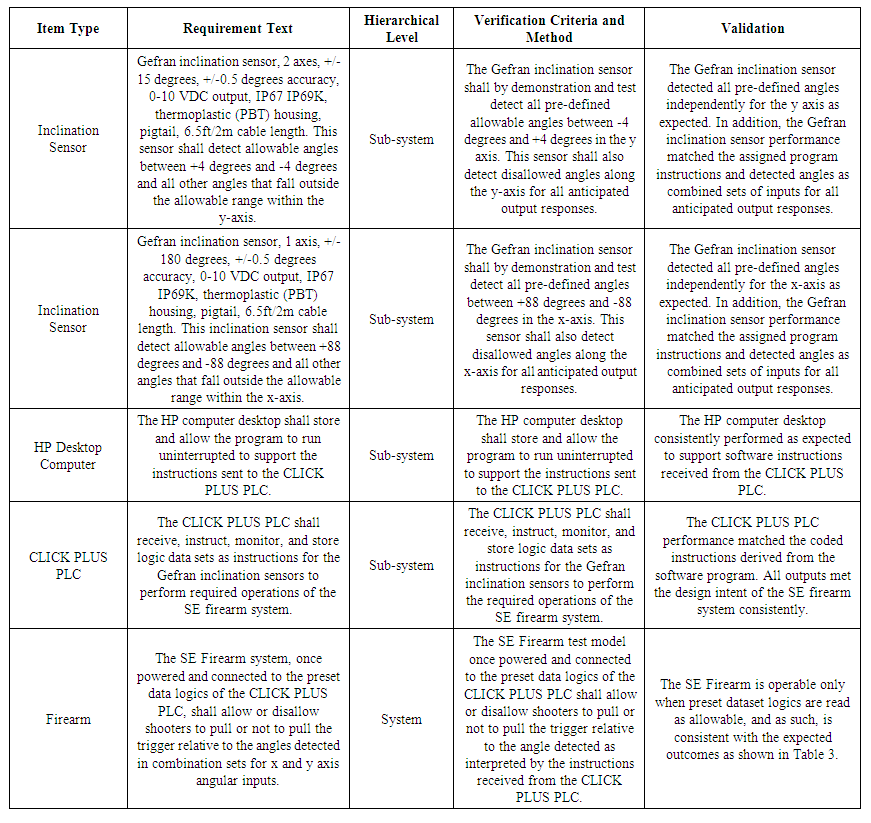

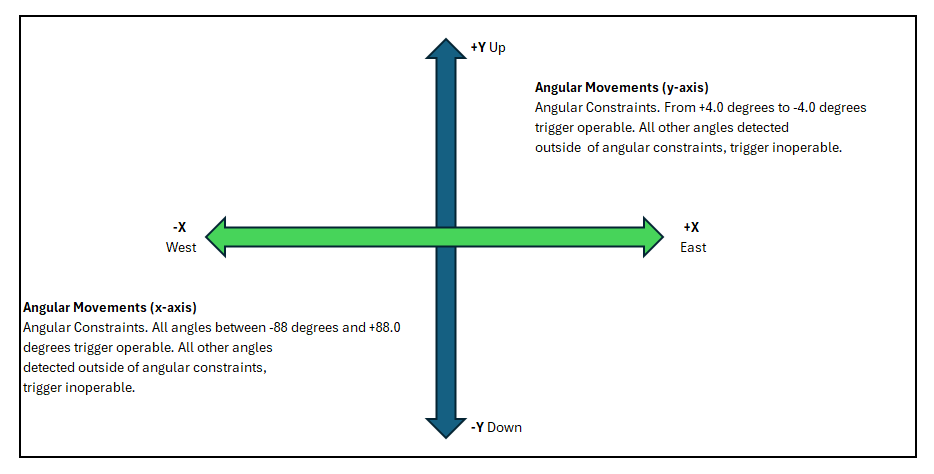

The SE firearm model shall disallow angles that are greater than or equal to 89 degrees for firearm movements within the x-axis (horizontal plane) pointing away or toward the shooter as shown in Figure 2. Conversely, the SE firearm model shall allow angles that are less than or equal to 88 degrees for firearm movements within the x-axis (horizontal plane) pointing away from the shooter. Any converted electrical signal within this range that is detected from a horizontal or x-coordinate position shall be interpreted as within the desired angular constraints and the trigger shall be operable. Angles that are detected between -4 degrees to +4 degrees for the SE firearm pointing away from the user in an upward or downward direction shall be allowed.  | Figure 2. SE firearm model cartesian coordinates shows when trigger is operable and inoperable relative to angular movements in the x-y coordinates |

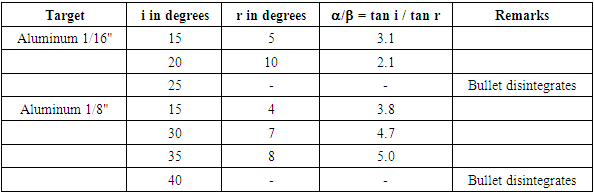

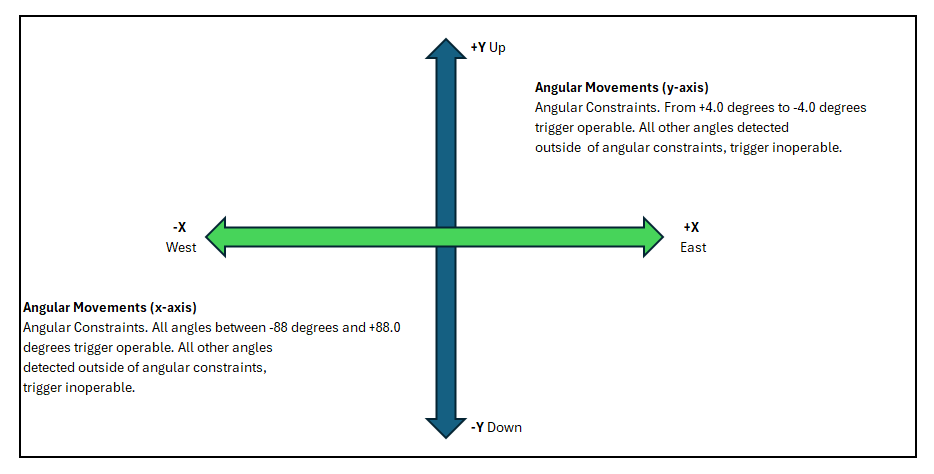

This notion has been tested and proven valid as the probability of ricochet is highest from surfaces approximately parallel to the axis of bullet movement, and grazing ricochets typically depart the surface at a smaller angle than the angle of incidence. For instance, studies have shown the order of magnitudes involved, where the ratio of α/β (where α and β are ratios of the moduli of component velocity vectors after and before ricochet) were calculated with the help of i and, r (where i and r represent the angles of incidence and ricochet respectively) data obtained with respect to metal plates. The calculations were given in respect of 1/16" & 1/8” thick aluminum plates fired upon by 178 grain .380, ball, MK2, K.F. revolver jacketed bullet at an incident velocity of 600 feet/s [5]. Conclusively, this study illustrates (see Table 6) that larger angles of incidence had bullet penetration losses from 23 to 100 percent penetration losses relative to subsequent angles of ricochet. On some instances, it is noticeable that the angle of ricochets totally disintegrated as kinetic energies on impact converted to potential energies almost simultaneously within the material. Bullet paths initiated from significantly smaller angles, as examined in this study, would produce extremely smaller angles of bullet ricochets as bullets would penetrate the same material superficially, and in some instances, with a graze. Subsequently, the calculated trajectory path as dictated by equation (1) results in bullet distances of 2,840 feet for an angle of incidence of 4 degrees which offers a safe haven for the user from bullet ricochets. Conversely, the trigger shall be inoperable for angles detected outside of the required range for all upward or downward directions of the model that points away from user. Table 6. Shows how angles of incidence relate to angles of ricochet with respect to 1/16” and 1/8” aluminum plates when fired upon by 178 grain .380, ball, MK2, K.F. revolver jacketed bullet at an incident velocity of 600 feet/second

|

| |

|

6.2. Functional Definition

The system elements within the SE firearm model are the basic building blocks. The building blocks include, first and foremost, the run switch located on the CLICK PLUS PLC, which is the only external point of contact for the shooter to initiate the operations of the security instructions of the SE firearm model. The run switch is an integral component that is responsible for initially receiving electrical energy to turn the circuit on, and conversely, to turn the circuit off manually. When the circuit is off, this condition conveniently disallows any attempted pull of the SE firearm trigger as it restricts the path of the trigger to be pulled by unauthorized shooters due to a unique coded instruction for initiation embedded in the systems software (see subheading 6.3.2 for more details) that can only be activated by the authorized shooter. Subsequently, this helps reduce the possibility of accidental firings. The run switch also interacts with other sub-systems, such as the inclination sensors that inevitably combine into functional desirable or undesirable outputs relative to the actions of the shooter. The primary functional subsystem that initially interacts and interfaces with the run switch is the 110V/120V supply that is regulated to 24V by the AC power supply module for the CLICK PLUS PLC to operate. Once the required voltage of 5V to 10V is received by the inclination sensors, then the required angular limits become activated to respond appropriately to the allowable output instructions received from the CLICK PLUS PLC. The electrical signal subsequently received with coded instructions allows the trigger to be operable. Concurrently, the inclination sensors detect angular values from the shooter’s reference point along the corresponding x-y coordinate. Once angles are detected from the x and y axes, an electrical signal is transmitted to the CLICK PLUS PLC where the codes are decoded, and the LED indicating green light glows green if the input received allows for an operable trigger activity.

6.3. Performance Requirements

6.3.1. Self-Inflictions

The performance requirements of the SE firearm are specifications of the operational characteristics of the system. To achieve the desired performance requirements, targets are set and become achievable, such as, output response for independent axes x and y, and combination sets to produce desirable operational outcomes, reliability, accuracy, and shooter experience. One arranged test performed, as shown in Figures 3 and 4, incorporates test segments that closely mimic the shooters’ activities in the real world. Several tests were performed for a variation of angle sets: 1) even angles of 22, 44, 66, 88, and 90 degrees and 2) odd numbered angles of 11, 33, 55, 77, and 89 degrees for SE firearm pointing away from user. The input test angles were tested on several instances for each set of pre-determined angles, except at the end of the first test readings, the second set of readings captured data when the SE firearm model points toward the shooter. Based on the test results, the performance of the SE firearm model is consistent for both sets of scenarios as no deviation between the results were observed. The results implied that any undesirable input, such as firearm pointing toward the shooter, and/or angle range limitations, such as 90 degree and higher, would immediately deter the shooter from pulling the trigger and subsequently prevent self-inflictions [6]. This desired output would not only deter the user from accidental firings, or self-inflictions, as the SE firearm would consistently not operate for every attempt made to pull the trigger and the user would become strongly discouraged and possibly frustrated by the ongoing non-responsive behavior of the firearm for those moments. From a design to manufacturing perspective, the idea here is to fully capitalize on the optimization process to ensure that all desired intentions of the SE firearm test model are justified before, during, and after operation. | Figure 3. Shows green LED light on at initiation for pre-defined x and y angles detected at +33.0 degrees and -1.9 degrees respectively |

| Figure 4. Shows green LED light off at pre-defined x and y angles detected at +100.0 degrees and +15.0 degrees respectively |

6.3.2. Accidental Firings

The course of developing the SE firearm system entails transforming the functional and operational requirements to produce a set of performance requirements. This step is especially important to allow subsequent phases of system development that are based on and evaluated using systems engineering practices. In order to support the security system development for this SE firearm model, implementations of innovative security criteria are adopted and written as a unique coded instruction to the CLICK PLUS PLC. This phase is highly critical to protect and prevent, in particular, unauthorized shooters from accidentally firing at any given moment. In order to integrate a security system data logic, the author integrated a clearly defined logic dataset that is coded to the CLICK PLUS PLC which is disclosed in this study for clarity. To accomplish this important coded instruction process, the author assumed that the SE firearm system for this study is a .38 caliber firearm with protective devices already integrated in the system as previously described. However, to make the SE firearm system very secure from external threats and accidental firings, a coded instruction is needed that is shared with an authorized shooter. Potential shooters would need to not share this information with anyone so as not to compromise the security system. The SE firearm studied is designed with written instructions for the tester (the author in this case) to carry out the instructions coded to the CLICK PLUS PLC. The instructions are based on angular movements in order to turn the SE firearm on. The instructions are: 1) The SE firearm test model must have an encrypted password that is linked externally to the SE firearm model from a central database known to the authorized user only. Once the correct password is acknowledged, the user can proceed to test the performance of the Click Plus PLC by connecting the programming cable to the computer and thereafter move the CLICK PLUS PLC switch to the run position. The SE firearm turns on the LED indicating green light instantaneously. This green glowing light shall stay on for 9 seconds to confirm that the authorized user successfully turned on the SE firearm test model. This test further showed on several instances that if it is not successfully turned on, then the SE firearm model will never be operable. These activities not only indicate consistency for the anticipated test results but confirm that this methodology is a viable solution to better manage accidental firings. The SE firearm was tested on several instances to closely examine the performance behavior of the system when allowable angular constraints were used correctly. The test results consistently showed that the SE firearm test model turned on at initiation as shown in Figure 3 and turns off as shown in Figure 4 when combined sets of angular movements in the x-y coordinates are invalid. Futuristically, the concept is to have a coded set of instructions to be unique and different for every SE firearm that adopts this innovative process accompanied by an enhanced architectural software element that will enable the system to operate wirelessly.

6.3.3. Assault by Gunshot Wounds

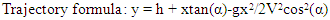

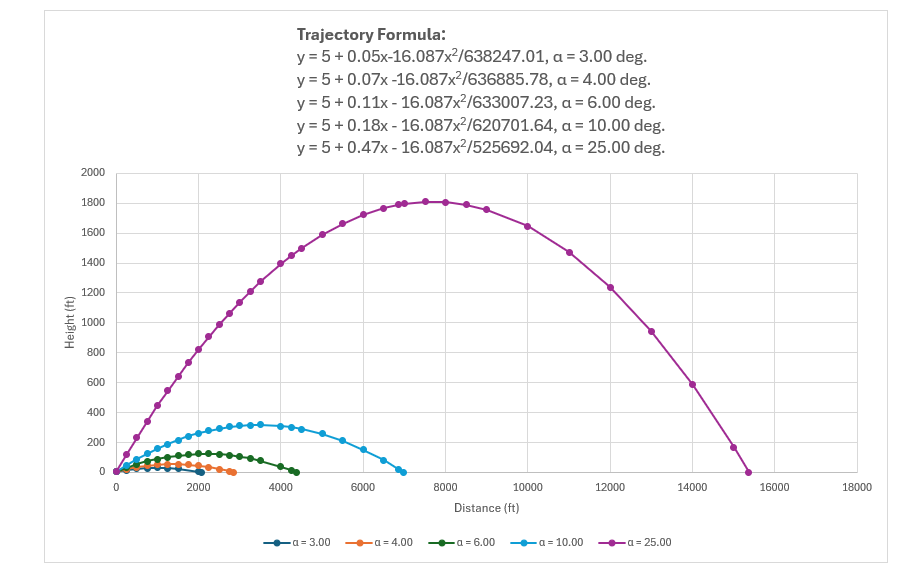

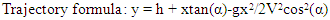

This study examined angular readings along the y-coordinate to understand and determine the behavior of the system in order to derive suitable inferences as to what constraints should be entertained. Readings taken at the previously defined angles of 3.00°, 4.00°, 6.00°, 10.00°, and 25.00° were used. So, from the SE firearm model test platform, the angular test readings show what is understood to be operable versus inoperable trigger activities. For this study, a .38 special caliber is assumed to be the baseline for the SE firearm model. All calculations for projectile motion trajectory for a .38 special caliber are based on initial discharge velocities between 800 ft/s to 1100 ft/s. This research examines the potential effects an 800 ft/s initial bullet velocity would have on shooter and bystanders in terms of potential self-inflictions (ricochets from bullets fired) that could cause injury or death from an initial height of 5 feet for the test launch angles previously mentioned. The verification method involved deducing the angle from the horizontal, α, and applying an analytical methodology to ascertain that the outputs were justified as true potentials to do no harm to shooters and bystanders. By way of further investigation, it is evident that an angle of launch of α at 25.00 degrees would potentially produce a final bullet trajectory landfall of 15,369 feet (4684m). The SE firearm model is programmed to disallow an angle of launch of 25 degrees which is equal to the universal joint’s maximum allowable angle. From analysis, the shooter has no possibility of seeing a human clearly at 15,369 feet. Subsequently, this design constraint deters any possibility for an assault to occur by gunshot wound. The design constraint allowable for the SE firearm model is dependent on the average linear distance humans can visually see another human clearly during daylight with a 20/20 vision. Research shows that the human eye under clear conditions with normal vision acuity — a rating of 20/20 — can gaze horizontally from around 5 feet (152.4 centimeters) above the ground, can potentially see about 3 miles (15,840 feet, or 4828m) into the distance, which is the point at which the Earth's curvature bends away so that the surface is no longer in view [7]. However, for an enhanced visual acuity to potentially see another human easily in the far distance based on a 20/20 vision acuity, the SE firearm model is designed to accept and allow trigger operations for angles of launch, α up to 4.00 degrees only, where a 4.00-degree angle of launch by analysis shall have a bullet trajectory landing position at approximately 2,840 feet (866m). At this distance, the SE firearm is designed to accept this angle as a maximum allowance, that is, to see clearly another human 2,840 feet away, and as such, it is based on the maximum baseline distance of 15,840 feet as previously mentioned [7]. This further suggests an object magnification of 5.6 times more than 3 miles. In other words, another human can be clearly seen about 0.54 miles away from the shooter. This angle of launch at 4.00 degrees or lower angles as shown in Figure 5, offers shooters an enhanced safety net from bullet ricochets or injury or death to the shooter and bystanders. If bullets are fired through launch angles α, greater than 4.00 degrees, then this potentially may cause injury or death to bystanders as shown in Figure 5 since visual acuity is significantly reduced [8]. The flight path or trajectory of a fired bullet for the SE firearm model shall be based on the trajectory formula shown in equation (1) [9]. | (1) |

where y = bullet trajectory maximum height, h = initial height, x = distance travelled, g = acceleration due to gravity, V= velocity of bullet, α = angle of launch.  | Figure 5. Shows angle of launch at 3.00°, 4.00°, 6.00°, 10.00°, and 25.00° with their respective trajectory paths and distances traveled |

6.3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis is used in this study to determine how “sensitive” the SE firearm model is to changes in the value of the parameters of the model [10]. In this paper, one main focus is given to parameter sensitivity. Parameter sensitivity is typically performed as a series of tests in which the modeler applies different parameter values to observe and assess how a change in the parameter causes a change in the dynamic behavior of the system [11]. The author shows also how the model behavior responds to changes in parameter values and subsequently uses sensitivity analysis as a tool to produce model building as well as model evaluation [11]. When building the system model, a number of uncertainties were considered, and as such, are addressed here to uncover those uncertainties through an in-depth sensitivity analysis study.

6.3.5. SE Firearm Test Platform

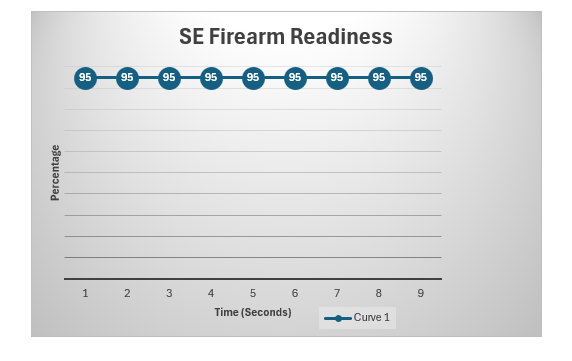

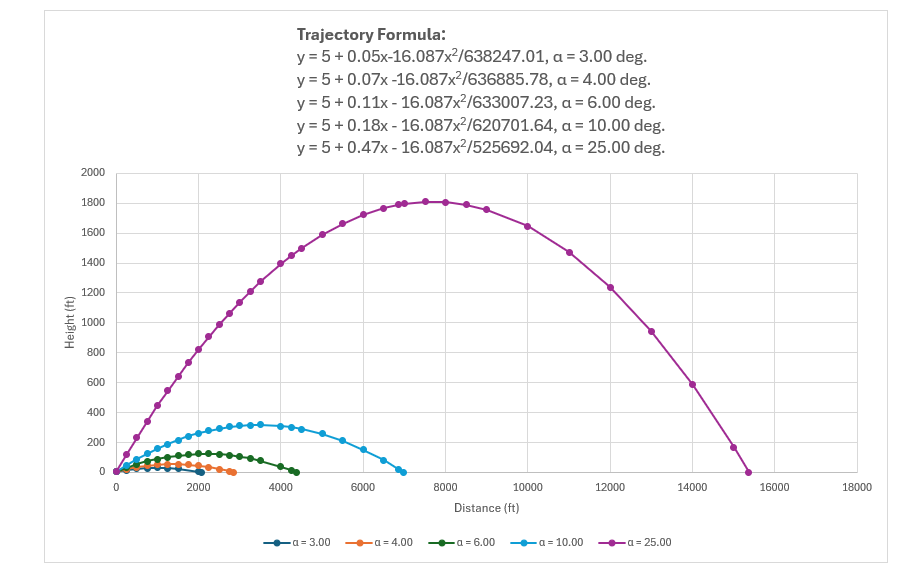

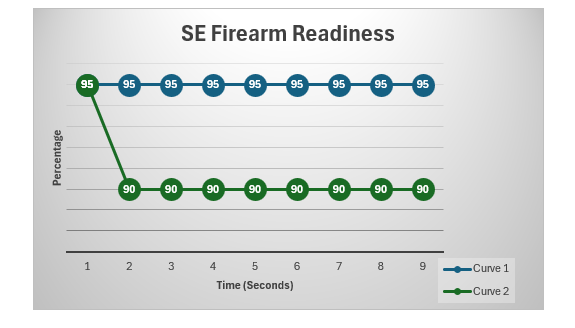

Assume for a moment that the SE firearm model is in a state of readiness when the firearm is pointing out at full arm’s length (about 24 inches) with the muzzle positioned at zero degree from the shooter’s chest region defined as the horizontal. However, this peaked position of readiness will decrease (Reduced Readiness) in the event the shooter increases the angle in either direction along the x-axis and even further if combined with upward and/or downward angular movements in the y-axis. In reality, the state of readiness will fluctuate and for those reasons the changes in parameter values will impact the time it takes the shooter to be able or unable to pull the trigger.The author examines the scenario further from the perspective that the behavior of the system is in equilibrium. The SE firearm model is tested over a full duration of 10 minutes of simulation. As a percentage, the state of readiness of the SE firearm model is noted to be approximately 95 percent, since the time it takes to be at peak readiness is 9.5 seconds out of 9 seconds based on previously established run times. Figure 6 shows the base run. | Figure 6. Base Run of the SE Firearm Model |

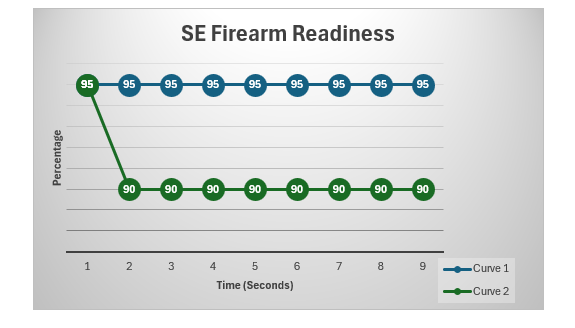

Next, we assume that the demand for launch angle changes from zero degrees to 4 degrees in the y-axis. At time 1 second, we introduce a step decrease of 1 percent in “Changing Angle of Launch.” Figure 7 shows the resulting behavior of “SE Firearm Ready” and “Changing Angle of Launch.” The system starts off in equilibrium but only remains in equilibrium during the first second. Immediately after the change in demand for a 4-degree launch angle, the state of readiness for the “SE Firearm Model” decreases slightly because “Changing Launch Angle” decreases together with “SE Firearm Ready.” To obtain the equilibrium value of 90 percent, one only needs to subtract the new value of “Changing Launch Angle,” to 90 percent per second, by the “SE Firearm coverage,” of 1 second. | Figure 7. The System Responding to a Step Change Angle of Launch at 4 degrees |

6.3.6. Changes in Angle of Attack

Using the change in “Angle of Attack in the X-axis,” we can now experiment with the model to see how the behavior resulting from disturbance changes under different parameter settings. When building the SE firearm model, we are often uncertain about the exact value of a parameter. However, it is important to be able to pick reasonable values for the parameters. Therefore, the values chosen should stay in a plausible range that could occur in the real-world system [11]. For example, in the SE Firearm model it would not be reasonable to expect the “Time to change or correct the angle of attack” to be just a few seconds. The shooter would need a longer time to perceive the change in the system, and then to correct the angle of attack so that the SE firearm is ready to be fired. On the other hand, a value of 25 or 50 seconds to correct the angle of attack would prevent the shooter from responding to a change in his/her readiness to fire the firearm readily. The SE firearm performance would be less efficient, resulting in a loss of reliability. However, the values of two or four seconds seem quite reasonable: as the shooter will have enough time to make the necessary adjustments to prepare for a more suitable angle of attack to pull the trigger more readily. The results of the sensitivity tests will indicate whether the conclusions drawn from the model can be supported even without being certain about the exact values of the parameters [11].

6.3.7. Changes in the Initial Value of SE Firearm Readiness

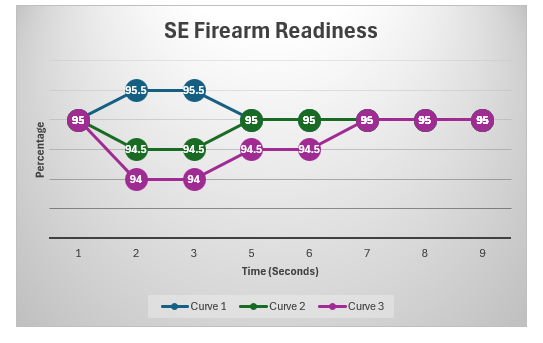

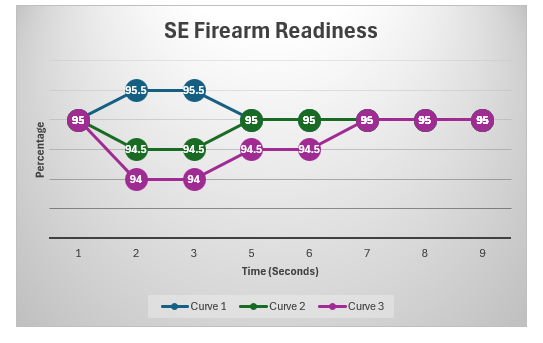

Finally, we can make changes in the initial value of “SE Firearm Readiness.” This value is set when the shooter prepares the SE firearm to be in a secure position for the initiation process each day. The shooter could have initial values of 94, 94.5, or 95 percent readiness, as shown in Figure 8.  | Figure 8. The Effect of Changes in the Initial Value of SE Firearm Readiness |

Notice also, that even though the behavior of the curves looks different from the ones in the previous simulations of this model, the general behavior has not changed [11]. Even when the shooter starts out with a reasonable degree of readiness, the behavior of the SE firearm model does not change greatly. When the initial SE firearm readiness is lower than what the equilibrium value should be, that is less than 95 percent, the SE firearm system readiness will be increasing during the first second, as in curve 1. When the initial amount is larger than 95 percent, the system will decrease for the first second, as in curve 3. However, after the step increase, all the curves immediately decline slightly, and then start slowly increasing to approach the same equilibrium value of 95 percent almost simultaneously.As expected, changing the value of parameters in the SE firearm model does make some difference in the behavior observed. Also, the sensitivity tests performed of the SE firearm model show that some parameter changes result in more significant changes than others. For instance, in Figure 7 the changes in “Time to correct the angle of launch” produce little difference in the behavior, while in Figure 8 the curves show the same behavior, but at different values of system readiness. This measure of more significant changes is studied through sensitivity analysis. In all scenarios, however, it is the structure of the system that mainly determines the behavior mode. We can conclude that, in general, but with exceptions, parameter values, when altered individually, only have a small influence on behavior [11].

7. Conclusions

According to the Results and Discussion, gun safety technologies can offer an effective and safer way to protect users from accidental discharge, suicidal shootings, and unauthorized use. This research clearly indicates that the rate of fatalities due to suicidal firing and accidental discharge already high, is increasing in many locales. The feedback from responders illustrates a common, growing concern for gun legislators to support the need to implement policies to invest in gun safety technology across all pertinent manufacturing platforms. The results also confirmed that limiting certain angular activities for firearms is a unique method and feature that would be well received and would warrant future research to be enforced expeditiously. The research for a safer haven to use firearms in a more responsible way with the application of angular sensors should be considered for further research and design efforts among licensed engineering organizations and certified trained personnel. One of the important implications of this work is that viable Systems Engineering principles can satisfy the objectives of making firearms safer to use. Consider, for example, the tests performed for this work claimed that for every angle that had the potential to either create self-inflictions, accidental firings, and or assault by gunshot wound, produced a trigger that became immediately inoperable. The combination of the input variables based on a sensitivity analysis indicates that there is a high correlation for allowable angles and the direction of pointing from the shooter, to produce only a small influence on the performance of the trigger. This research clearly suggests that there are valid reasons to integrate systems engineered protective devices in firearms to produce logical communication between embedded devices that would offer immediate and accurate responses to prevent self-inflictions to shooters, accidental firings, and assault by gunshot wounds. This research also implies that current standards should be made technologically obsolete as soon as possible. It is necessary, therefore, to address the prevailing issues and capabilities raised in this paper to mitigate self-inflictions, accidental firings, and assault by gunshot wounds. By implementing protective devices within firearms with a well-defined proven technological process, we can significantly help deter inadvertent discharges, unwanted injuries, and deaths.

References

| [1] | Quenzer Faith, Townsend Ricard, Ercoli Frank, Givner Andrew, Dirks Rachel, Coyne Christopher J.: Self-Inflicted Gun Shot Wounds: A Retrospective, Observational Study of U.S. Trauma Centers. May 2021 PubMed Central. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8203010/. |

| [2] | Hung Eric, Kriss Megan, 2023, 5 Best Gun Trigger Locks: Pistols & Rifles. https://www.pewpewtactical.com/best-gun-trigger-locks. |

| [3] | Identilock, The World’s First Biometric Fingerprint Trigger Lock, Now Shipped By Opticsplanet, 2018. https://getidentilock.com. |

| [4] | Gramlich John, 2025. What the Data Says About Gun Deaths in the U.S. https://www.pewsearch.org/short-reads /2025/03/05/what-the-data-says-about-gun-deaths-in-the-us/. |

| [5] | Mohan Jauhari, Mathematical Model for Bullet Ricochet, 61 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 469 (1971). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol61/iss3/12. |

| [6] | Fletcher Wayne. What is the Safest Direction to Point a Firearm? February 18, 2024. https://thegunzone.com/what-is-the-safest-direction-to-point-a-firearm/. |

| [7] | Kiger Patrick J: How Far Can the Human Eye See? March 15, 2023. https://science.howstuffworks.com/question198.htm. |

| [8] | Davis Margret. How Far Can the Human Eye See? Unveiling the Extensive Range of Eyesight. November 1, 2023: https://www.sciencetimes.com/articles/46850/20231101/far-human-eye-see-unveiling-extensive-range-eyesight.htm. |

| [9] | Ben Adena, Pamula Hanna, Bogna Syzk: Trajectory Calculator. October 29, 2024. |

| [10] | Iooss, B., Saltelli, A., Ghanem, R., Higdon, D., Owhadi, H. (2015). Introduction to Sensitivity Analysis. (eds) Handbook of Uncertainty Quantification. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-11259-6_31-1. |

| [11] | Breierova Lucia, Choudhari Mark. An Introduction to Sensitivity Analysis. https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/15-988-system-dynamics-self-study-fall-1998-spring-1999/abda6cf0e50977bf 369a53fe6c4deb0a_sensitivityanalysis.pdf https://www.omnicalculator.com/physics/trajectory-projectile-motion. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML