-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Journal of Safety Engineering

p-ISSN: 2325-0003 e-ISSN: 2325-0011

2016; 5(1): 17-26

doi:10.5923/j.safety.20160501.03

Building Construction Workers’ Health and Safety Knowledge and Compliance on Site

Peter Uchenna Okoye , John Ugochukwu Ezeokonkwo , Fidelis Okechukwu Ezeokoli

Department of Building, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Peter Uchenna Okoye , Department of Building, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

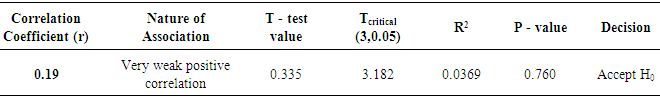

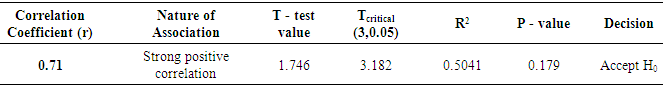

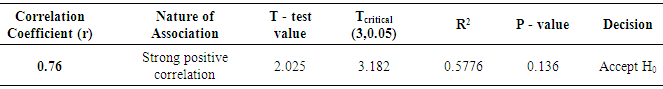

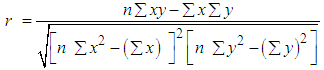

The study examined the health and safety knowledge and compliance of building construction workers on site in Anambra State, Nigeria. Questionnaires containing information relating to health and safety at site were administered randomly to the construction workers selected from fifteen (15) selected building sites across the state. Mean Score Index and Pearson’s Product-moment Correlation Coefficient(r) were statistical tools used for analysis of results. The result revealed that there was moderate level of health and safety knowledge, and low level of health and safety compliance among building construction workers in the state. It also found that the effect of the health and safety knowledge and compliance on project performance was low. The result established a very weak positive correlation (r=0.19) between health and safety knowledge and compliance. It further established a strong positive correlation between health and safety knowledge and project performance (r=0.71); and between health and safety compliance and project performance (r=0.76). However, when the significance of the correlation was tested, the t-values obtained were (0.335), (1.746) and (2.025) respectively. From the result, all the t-values were less than the t-critical (3.182) at 5% significance level. The result implied that though there were relationships between all the variables considered, the relationships were not significant. Practically, this meant that health and safety knowledge and compliance alone cannot substantially improve the project performance, but was limited to the values of their coefficient of determination (R2) 50.41% and 57.76% respectively. Thus, since knowledge and compliance alone cannot achieve optimum project performance improvement, some other factors such as management commitment, workers involvement and strict enforcement of safety regulation should be applied to complement. In this case, establishment of the Anambra State Safety Commission whose function would include inter alia; policy formulation, setting of safety standard for all sectors in the state is of paramount important.

Keywords: Compliance, Construction Workers, Health and Safety, Knowledge, Project Performance

Cite this paper: Peter Uchenna Okoye , John Ugochukwu Ezeokonkwo , Fidelis Okechukwu Ezeokoli , Building Construction Workers’ Health and Safety Knowledge and Compliance on Site, Journal of Safety Engineering, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2016, pp. 17-26. doi: 10.5923/j.safety.20160501.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The Nigeria construction industry has continued to occupy an important position in the nation’s economy. In 2012, construction sector contributed about N121, 900.86 million Naira to the Gross Fixed Capital Formation, and employed 6,913,536 personnel [1], excluding the casual workers. In 2014, its share of the total GDP was 3.82% [2]. The range of professions in the industry is also huge. It includes not only the workers and managers on the site, but also the architects, designers, engineers and other specialist professions. Although, Nigeria is enjoying relatively strong growth in construction activities, efforts towards ensuring improved safety performance have yielded minimal results. The enforcement of safety regulations is not widespread within the industry. More construction workers are killed, injured or suffers ill health than in any other industry [3]. It is however, disheartening that despite several efforts towards improving the health and safety status of Nigeria construction industry, continuous increases in the number of accidents both reported and unreported on construction sites still go unabated.Furthermore, Nigeria has a very high accident record attributable to lack of effective monitoring, reporting and control practices. Added to this problem is the incessant collapse of building in the country. Although there has been a dramatic improvement in recent decades, the construction industry safety record has continued to be one of the poorest [4]. Neale [5] believes that improving occupational safety and health (OSH) in the construction industry is a slow but achievable process. Thus, occupational health and safety in construction work should start at the designing table and continue throughout the construction phases until the safety and health of end users is ensured due to the complexity of the industry and the hazards it contains [6].As a state on transition, Anambra State is one of the few states in Nigeria that is witnessing tremendous infrastructural development especially with respect to building projects. Almost all these projects are being handled by the local contractors and construction workers. In recent years however, there has been increased cases of construction sites accidents in the state. Majority of these accidents are unreported. Thus, the issue of whether these workers have adequate knowledge on health and safety issues and whether they comply with health and safety rules and guidelines on site come to fore.Like in every other business environment, construction business should be guided by certain regulations to ensure health and safety of its workers. According to [7] safety and health have become an integral component in the workplace as employers, labour unions and others engage in trainings and procedures to ensure compliance with safety standards and also to keep a healthy workforce. Famakin and Fawehinmi [8] assert that the increasing rate of construction accidents has increased the level of awareness of construction health and safety, thereby involving its inclusion as part of project performance criteria.Ayininuola and Olalusi [9] aver that non-existent and/or lack of enforcement of construction health and safety regulations, and bylaws are among the major causes of building failures. They opine that health and safety in construction is a highly practical guide to help any professional understand the implications of health and safety legislation for their role in a project. However, the fact that health and safety performance of the Nigeria construction industry is culturally linked makes the situation more challenging. Nigerian cultures are known to be unique. Like any other African countries, Nigeria culture has been generally characterised as collectivist, high power distance, average uncertainty avoidance, masculinity, having short-term orientation and indulgence [10-16]. This means that Nigeria needs laws and regulations which cannot ordinarily be observed but must be made known and enforced or persuaded to be complied. According to [17] the physical work environment is not of much value in Nigeria. This is because of the prevalent unemployment, the value attached to life, widespread corruption, the disdain of the ruling class and the labour aristocrats to the plight of the workforce which led to a very weak, outdated and lax health and safety laws and regulations; compounded by bad planning laws and low monetary compensation paid for infringement of even the lax laws [17].The issue remains that if there is adequate health and safety knowledge and compliance with health and safety rules among construction workers will this translate to project performance? It is against this premise that this study tends to examine the health and safety knowledge and compliance of building construction workers on site in Anambra State, Nigeria with a view to determining the:1. Relationship between the health and safety knowledge and compliance of the workers.2. Relationship between health and safety knowledge of the workers and project performance.3. Relationship between health and safety compliance of the workers and project performance.Meanwhile, this paper is organised into five sections for clarity. The introduction presented the background of the study which culminated into the aim and objectives of the study. The Literature review presented the results of existing studies while taking a particular reference to the construction health and safety management system, safety performance, safety regulations, safety knowledge and compliance and identifying the gaps therein. The methodology adopted in carrying out the study is presented in the methodology section while the results of the study are presented and discussed in the next section. Finally, conclusion section contains the general outcome and the success of the study, including the recommendations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Construction Health and Safety Management System

- Bhutto, Griffith and Stephenson [18] argue that in the modern business environment, occupational health and safety (OHS) is a very sensitive management responsibility that influences the very survival of organisations in some extreme cases. That is to say that construction projects do not operate independently of the society in which they are located [5]. Thus, the emergence of new regulations, laws, standards and codes has also made many construction organisations to improve their safety performance. Agwu [19] insists that construction industry must not approach construction safety as just another step in avoiding unwanted accidents/costs but as a strategic tool for maximising competitiveness and profitability. In this regard, total safety management was proposed by [19] as a performance- oriented approach to construction safety that gives an organisation a sustainable competitive advantage in the global marketplace by establishing a safe work environment that is consistent with peak performance and continuous improvement through the integration of all aspects of construction safety (intention, behaviour, culture and process). In Nigeria however, [20] report that the perspectives of most industries and organisations show that the stage of occupational health and safety is still at infancy in the country due to employer/employee attitudinal behaviour, lack of safety culture and non-implementation of OHS policies. In addition, only big multinationals recognise occupational health and safety and run the policies as constituted in their parent countries of origin [20].Meanwhile a typically effective safety management system should encapsulate the actions managers at all levels take in order to create an organisational setting in which workers will be trained and motivated to perform safe and productive construction jobs [21]. For [22], effective safety management is both functional (involving management control, monitoring, executive and communication subsystems) and human (involving leadership, political and safety culture sub-systems paramount to safety culture). Al-Kilani [23] suggests that safety management must be thorough, and it must be applicable to all aspects of the job, from the estimating phase of the project until the last worker has left the premise at the completion of the project. In this regard, the [24] advocates that organisations shift from traditional safety management approach, which is reactive to a modern approach that is more proactive.

2.2. Construction Health and Safety Performance

- Workplace Health and Safety is a global challenge to the sustainable development and civilisation. The health and safety performance of the construction industry remains a staring challenge in its effort to tackle the developmental initiative of many nations including Nigeria. Udo, Usip and Asuquo [25] reveal that the neglect of safety on sites may have considerable impact of worker productivity and performance and capable of undermining the reputation of construction companies thereby increasing expenses.In Libya for instance, [23] shows that there was still a lack of commitment from the government, the insurance company, the labour ministry, the owners, consultants, and the contractors to improving safety performance on the construction sites. According to [26], the very high prevalence of informal work, outside the mechanisms of labour legislation, further complicates efforts to improve OSH in Southern Asia. Walker and Pratap [26] maintain that regulations are almost always directed at the employee-employer relationship, enforced by a state, which not only excludes informal workers from their coverage but has created an incentive to do so. Although calls have been made to the stakeholders in the industry to improve their health and safety performance [27], the number of fatalities and injuries arising from construction activities across the country as at today is highly worrisome. Hinze [28] states that improvement of safety performance can only be effective if construction firms is structured and positioned to make changes when it is deemed appropriate. Hinze [28] suggests a shift in thinking where the focus is on those actions that can lead to good safety performance. For [29], a better approach is to focus on proactive efforts dealing with the factors responsible for such accidents and injuries and how to control them.

2.3. Construction Health and Safety Regulations

- Chudley and Greeno [30] define construction regulations as statutory instruments setting out the minimum legal requirements for construction works and relate primarily to the health, safety and welfare of the workforce which must be taken into account when planning construction operations and during the actual construction period. Regulation cannot on its own be effective without enforcement. Anderson [31] and Idubor and Osiamoje [32] opine that regulations without proper enforcement are tantamount to no laws. World over, health and safety regulations governing the construction industry and other work related industries exist. In Nigeria also, a number of legislations on occupational health and safety exist. These include; Labour Act of 1974 modified to Labour Acts 1990, and updated to Labour Act, Cap L1, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria (LFN), 2004; the Factories Act of 1987 which became effective in 1990 and later updated to Factories Act, Cap. F1, LFN, 2004 [33], [34]; the Workman’s Compensation Act of 1987 which became effective in 1990, modified to Workman’s Compensation Act, Cap W6, LFN, 2004 and repeal to Employee’s Compensation Act, No. 13, 2010 of the laws of the Federation of Nigeria [35], the Insurance Act, 2003 [36] and the Labour, Safety, Health and Welfare Bill of 2012 including the National Building Code Enforcement Bill which has suffered huge political setback over the years, and is yet be passed into law by the National Assembly. The Federal Ministry of Labour and employment is saddled with the responsibility of enforcing the Factories Act and Employee’s Compensation Act, while the Labour, Safety, Health and Welfare Bill of 2012 empowers the National Council for Occupational Safety and Health of Nigeria to administer the proceeding regulations on its behalf. In the developed countries such as UK, USA, Australia, Singapore and Germany, these regulations are well developed and functional. However, despite being among the countries that signed the occupational health and safety law in the Geneva Convention of 1981, the pathetic health and safety situation in Nigeria construction industry still pervades.In spite of numerous statutory provisions and expectations in Nigeria, gap still exist in health and safety management [37]. This gap is largely due to a dysfunctional health and safety law, causing an apparent lack of regulation of health and safety in almost every sector of the economy. Adeogun and Okafor [20] contend that these acts are not being enforced in Nigeria as evidenced from the reports of unhealthy exposure to risks of workers and employees in various organisations. According to [38] the Ministry charged with enforcement of these laws has not been effective in identifying violators probably due to inadequate funding, lack of basic resources and training therefore, consequently neglect safety oversight of other enterprises, particularly construction sites and non factory works. Umeokafor, Isaac, Jones and Umeadi [39] agree that the impact of the enforcement authority is ineffective, as the key stakeholders pay less attention to OSH regulations; thus, rendering the OSH scheme dysfunctional and unenforceable, at the same time impeding OSH development. To this end, [37] attributed the failed OSH management system to the non-functional OSH regulations and provisions. Idoro, [40] linked the problem to adopting almost all existing regulations of reference on health and safety in Nigeria from foreign countries, especially from the British legal system with little or no changes made [41].Kolo [41] further observes that some provisions from these laws do not necessarily meet the conditions experienced in Nigeria. In addition, the labour law does not provide workers with right to remove themselves from dangerous work situations without loss of employment. Nevertheless, the emergence of new regulations, laws, standards and codes has made many construction organisations to improve their safety performance.

2.4. Construction Health and Safety Knowledge

- Knowledge is more than information, since it involves an awareness or understanding gained through experience, familiarity or learning [42]. Article 23 of the Factories Act F1 LFN 2004 [34] specifies training of workers. However, the relationship between knowledge and information is interactive [42]. But according to [43], one of the major needs with regard to the construction industry is to enhance professionals’ interests in active safety management and implementation of awareness programs, which must be developed and implemented among construction workers. Akinwale and Olusanya [43] argue that awareness on possible risk factors and knowledge on how to reduce these risk factors among workers and contractors will enhance site safety.Safety knowledge therefore, encompasses awareness of occupational health and safety risks, including an evaluation of occupational health and safety programmes in an organisation [44]. Sources of safety knowledge according to [44] include incident investigation, teamwork, collaborations, and survey of safety culture. Problem solving entails specific decisions on occupational health and safety risks in an organisation. This implies decision-making for the maintenance of occupational health and safety. Knowledge creation is dependent upon information, yet the development of relevant information requires the application of knowledge [45].The role of trainings in promoting health and safety has also been highlighted by [32], [46]. Kumar and Bansal [47] argue that effective safety knowledge among construction professionals can reduce accidents that directly or indirectly reduce project cost, because in developing countries, safety rules usually do not exist, and if exist; regulatory authorities are unable to implement such rules effectively. The above view is supported by [48]. However, [49] suggest that employees, including project personnel, should be equipped with safety skills and with necessary safety knowledge to enable them to work safely and to encourage others to do the same. As such, construction organisations should advance a climate which values safety learning. On this basis, [29] infer that safety learning should not only be considered as an acquisition of knowledge through instructions and training in classrooms or other formal settings rather safety should be considered as the final outcome of a dynamic and collective construction process. In this case, a safe workplace is the result of constant engineering of diverse elements, such as knowledge and skills, equipment, and social interactions, which are integral to the work practices of various project stakeholders [50].

2.5. Construction Health and Safety Compliance

- Hawkins [51] describes compliance as applying measures designed to comply with legal requirements with the regulator being primarily more concerned with improved outcomes than prosecution results. According to [32], lack of strict enforcement of OSH regulations enables non- compliance to OSH regulations; while [39] state that non-compliance to OSH regulations is a major contributor to the poor state of OSH in Nigeria. Hence compliance with Occupational Health and Safety legislations can increase productivity in industries by reducing accidents, because accidents result in decreasing productivity and damage to equipment or property [51].On the other hand, OHS measures are said not to be effective in improving safety and health conditions in workplace [52]. Kamau [52] claims that OHS regulations are just symbolic gestures and useless. Thus the prevalence of health and safety abuses on construction site among construction stakeholders calls for an intensive investigation into the level of health and safety knowledge and compliance of construction workers. This is because enforcement and compliance with OHS regulations are not the standalone steps for improving OHS, as improving organisational culture can also improve OHS [39]. This therefore, implies that regulation without strict compliance and management commitments amounts to waste of time and resources.

3. Methodology

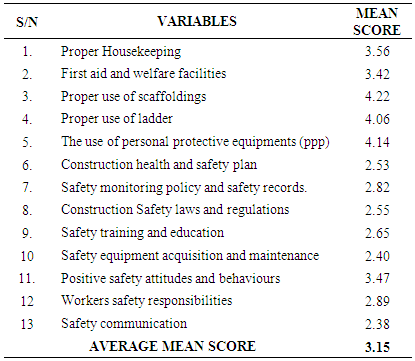

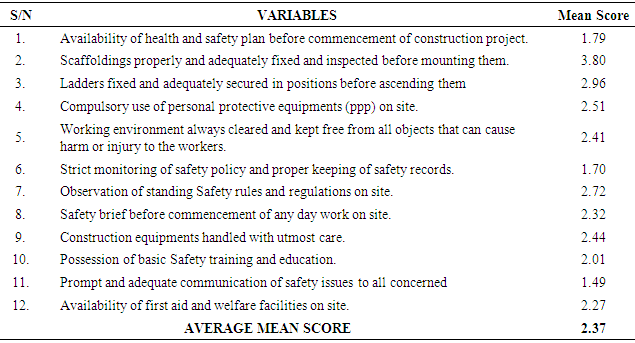

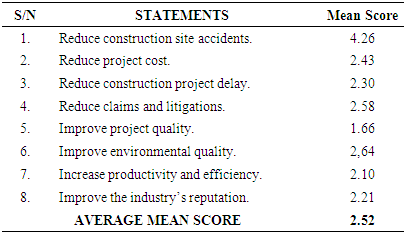

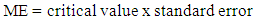

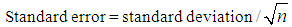

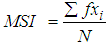

- This study was a survey research which made use of questionnaires containing a well structured preformatted set of information bordering on workers health and safety knowledge, compliance and project performance. Apart from the demographic information about the respondents, questionnaire contains thirteen (13) statements on health and safety knowledge, twelve (12) statements on compliance with health and safety rules, and eight (8) statements on the effects of health and safety knowledge and compliance on project performance. In each of the statements, respondents were required to express their opinion on a five point Likert-type scale, where 1 = very low, and 5 = very high.Almost all construction works going on in the state are being handled by the local contractors and construction workers. Though there were more than one hundred construction projects going on in the state at the time of this study, only fifteen (15) construction sites were selected based on the nature of the project, the scope of the project, the organisation of construction site, variety of construction workers involved, the stakeholders involved in the project and the location of the project. Vast majority of construction projects in the state were privately owned residential building projects with the owner being the contractor and involving few construction workers usually coming to work when their services were demanded. Secondly, majority of these projects were not organised and do not have regular construction activities going on in them, besides the selection needed to have a geographical balance. To ensure geographical spread, five sites were selected from each zone of the state. The questionnaires were administered to 190 construction workers (artisans) of various trades who were randomly selected. Out of this total number, 148 questionnaires were retrieved and used for analysis. This represents a response rate of 77.89%. To ensure reliability, the margin of error was computed at 95% confidence interval (C.I) within which the result would be acceptable. Margin of error (ME) is given as:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

4. Results and Discussions

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- Continuous health and safety challenges resulting to different types and magnitudes of losses including loss of lives on Nigeria construction sites and Anambra State in particular has continued to attract great concerns. Sometimes it is said that knowledge is power, but misapplication of knowledge is disastrous. In view of this, this study has examined the level of construction workers’ health and safety knowledge and compliance and how they can translate to project performance on construction sites in Anambra State, Nigeria.This study has found that the level of health and safety knowledge among the construction workers in the state was moderate. It also found that the level of health and safety compliance among the workers was low. The result further revealed that effect of health and safety knowledge and compliance of construction on the project performance was low. It went further to establish a very weak positive correlation between the health and safety knowledge and compliance of construction workers. This relationship was found not to be significant. In the like manner, the result established that there was strong positive correlation though not significant between health and safety knowledge and project performance; and between health and safety compliance and project performance. The study concluded that though there was positive relationship which suggest that health and safety knowledge and compliance to health and safety rules were related, this would not be translated that health and safety knowledge would automatically ensure compliance. This study further averred that health and safety knowledge and compliance alone cannot substantially improve project performance even though both show strong positive correlation with project performance. This implies that knowledge and compliance alone are not enough to cause behavioural changes required for safety performance but a certain aspects of safety culture are required. These other essential safety factors include: enforceable regulatory framework, management commitment, workers involvement, etc, which must also be considered for an improved project performance.Of utmost importance is the setting within which the study was conducted. Since almost all the construction works going on in Anambra State are being handled by the local contractors and construction workers, this study has highlighted the need for effective and enforceable health and safety regulations in the State. Based on the result of this study, this would serve as a wakeup call to agencies responsible for ensuring strict implementation of safety rules on construction sites, if any in the State.However, the provisions of National Building Code as regards to health and safety on construction site is very obvious, adherence to that provisions will definitely maximise safety performance of our construction sites. To improve the health and safety performance of construction industry in the state, the Anambra State government should establish the Anambra State Safety Commission whose function would include among others; policy formulation, setting of safety standard for all sectors in the state, issuance and withdrawal of safety compliance certificates at all levels, conduct of safety training, seminar and workshops, public enlightenment/ awareness creation, etc.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML