-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2022; 7(1): 1-9

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20220701.01

Received: May 20, 2022; Accepted: Jun. 5, 2022; Published: Jun. 13, 2022

Assessment of the Causes and Treatment of Female Infertility in Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan

Sajida Riaz , Sanaullah Panezai

Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan

Correspondence to: Sanaullah Panezai , Department of Geography and Regional Planning, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Infertility is a worldwide health issue affecting nearly one-tenth of couples. Many women without children declare it their destiny and render it in several ways, concluding it is God’s will. In Pakistani society, infertility is generally considered taboo. Objective: The study aimed to identify the perceived causes of female infertility and the treatments sought by female infertility patients in Quetta, Balochistan. Methods: For this research study, a semi-structured questionnaire was used for data collection. A multi-stage sampling was adopted, and 39 teachers of government girls’ colleges in Quetta, Balochistan, province were selected through purposive sampling as respondents. Findings: The findings revealed that two-thirds of the respondents (41%) were in the age group of 31–39 years. It was further found that the duration of infertility for most of the respondents was 6–8 years. Almost two-fifths (43.6%) of the respondents were lecturers. The finding further showed that 64.1% of the respondents had a master's-level qualification. Almost half of them were living with an extended family. The results revealed that God’s anger, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), inherited infertility from the family, evil spirits, and the curse of the family were the perceived causes of infertility. Moreover, menstrual disorders, problems in the fallopian tube, uterus, and cervix, and sexual disorders were the clinical causes of infertility. The majority (74.4%) of the respondents reported good economic conditions. In the case of more than half (56.4%) of respondents, both partners were infertile, and 69.2% of them had not taken any treatment yet. Conclusions: The study suggests that the government needs to incorporate the perceived and clinical causes of infertility into their treatment strategies at healthcare facilities. This study suggests the arrangement of awareness campaigns to educate them about the clinical causes of infertility and encourage them to seek medical treatment. Future research may be conducted with the general population in urban and rural settings.

Keywords: Infertility, Female infertility, Causes of female infertility, Infertility treatment, Infertility in women, Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan

Cite this paper: Sajida Riaz , Sanaullah Panezai , Assessment of the Causes and Treatment of Female Infertility in Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2022, pp. 1-9. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20220701.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Infertility is defined as the incapability to develop expectant after a single year of sexual contact lacking any contraception. For females age 35, this disorder is analyzed next 6 months of incapability to consider (Larsen, 2005). The most common definition is given by World Health Organization (WHO), according to that definition, infertility is the situation when a couple doesn’t conceive within two years of regular sex without any contraceptive, on the other hand, according to reproductive health outlook infertility globally affected 8 to 10% of couples (Aseffa, 2011). Globally, one-third of infertility issues are found in females, the other one-third in males, and the last one-third impacts on both male and female (Leke et al., 1993). Infertility is a global issue that is a threat to the overall social life of a couple. People of different professions have different definitions of infertility according to their fields (Larsen, 2005). Most poor countries have socio-economic and socio-cultural and environmental impacts on the widespread presence of infertility (Rutstein & Shah, 2004). In most societies, women are blamed for infertility and it is shame and stigma for them (Ombelet et al., 2008). In many societies, the main purpose of life is giving birth to children (Gerrits, 2002).Infertility has been regarded as a disease because the reproductive system fails to achieve pregnancy despite lacking the protection of copulation (Ericksen & Brunette, 1996). Male partners can be apprised of sterility by using the various treatment method and form rating serum on the testing ground (Leke et al., 1993). Basically, two types of infertility exist. The first type is called primary infertility where those couples who did not have a child for one year even after using contraceptives or without any contraceptives whether it’s a traditional or non-traditional method of contraceptives. Whereas, the second type determines those couples who had a child but are not now able to have a child anymore (Bayouh, 2011). Fertile age in women is comprise of 15-49. A woman is not conceiving in this period instead of not using any preventative measure for two years can be termed as infertile. In many countries, infertility has been found due to blood infection, unsafe abortion, and long illness can also cause inability to reproduce. Infertility is the 5th highest serious physical or mantel condition that limits a person’s movements, senses or activities. In some cases, the causes are unknown. In some cases, the causes are unknown. According to one study, people who begin having sex before the age of 13 are at a high risk of infertility. (Leke et al., 1993). The most common causes of infertility are fallopian tube dysfunction, uterine problems, irregular menstrual cycles, sexual disorders, and ovarian failure. The aetiology is distributed fairly equally among male factors, ovarian dysfunction, and tubal factors: "Diabetes mellitus"; "thyroid disorder"; "undiagnosed and untreated coeliac disease"; "adrenal" disease; "hypothalamic-pituitary" factors "hyperprolactinemia"; "hypopituitarism." "Thyroid glands" disturb the female period cycle. The presence of anti-thyroid antibodies increases the ratio of infertility; therefore, due to these diseases, infertility is occurring in the world (Poppe et al., 2002). The major cause of infertility in the world that can be cured is pelvic inflammatory disease, which is caused by sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (Andrews, 2005). The medical community is well aware of the dangers of STDs. As STDs are the foremost cause of infertility in many childless women, many childless women had been infected by the virus that causes infertility. Religious treatment is the most commonly used method and appears to be the easiest for childless women to select. Even in the twenty-first century, this is the most powerful sociocultural norm. Many studies show that children have great impertinence toward their parents. Repeated divorce and remarriage have been shown to have an impact on children's marriages during divorce if women lose their wealth, making it difficult to find a desirable partner (Link & Phelan, 2001).Furthermore, marriage before the age of 10 to 12 years is risky for fertility, and marriage after the age of 30 years is also risky for conception and pregnancy. Smoking is another cause of infertility in both men and women. Smoking is a cause of female infertility among sexually transmitted infections (STIs). These infections have the power to destroy the fallopian tubes in females. Smoking also damages the DNA. The disordering of DNA affects male sperms, affecting male fertilization or fertility; excessive alcohol consumption causes infertility. Furthermore, both males and females are affected by infertility caused by obesity, eating disorders, diet and exercise, or excessive work (Andrews, 2005). Research studies report that sociocultural and economic impacts are directly related to infertility. The analysis of the evidence indicates that economically poor areas face socio-cultural factors that contribute to infertility. Due to their low income, they cannot afford treatment for infertility, although it is a disease, but the affordability of the treatment makes it curable (Van Balen & Bos, 2009). In Pakistan, research studies have revealed the socio-cultural and economic consequences of infertility. In a study on infertility in Pakistan, Abbasi et al. (2016) report that infertile women experience negative social consequences such as stigmatization, marital instability, and abuse. Infertility compounds anxiety, depression, and other marital troubles, including stress from family (Ali et al., 2011). In Pakistani society, infertility is considered taboo, which is why researchers avoid such topics. It has been observed that people avoid giving data regarding such issues. Apart from that, infertility has been explored less. This research will help to find the actual number of infertile working women employed in colleges. Every time women are blamed for being infertile, the ratio of infertility is higher in men. This dogma of childlessness is always on women, and working women are especially vulnerable to it due to stress (Dyer et al., 2004).According to research studies, one-fifth of the population of Pakistan is facing infertility issues. In Pakistan, the federal government formulates health policies, and these policies are aimed at providing quality health care and opportunities to all of Pakistan's population (Panezai, 2017). Basically, healthcare is a systematic method for the diagnosis of diseases, their treatment, prevention, and injury management to ensure safe health. There are two types of health care that are known to respond to diseases: curative and preventive. Curative health care is a type that focuses on curing the patient by diagnosing his disease and then providing him or her with a treatment to solve his medical issue. While the preventative type focuses on disease prevention and health maintenance through vulnerability assessment and mitigation (Panezai, 2012). Several research studies have reported that there is a lack of medical facilities and well-equipped medical hospitals, mostly in rural areas of Pakistan. Due to this, many couples cannot gain access to medical facilities to cure themselves (Ali & Panezai, 2021; Bazai & Panezai, 2020; Hameed et al., 2021; Panezai et al., 2020; Panezai et al., 2019). Poverty in Pakistan is one of the reasons that infertile couples with low incomes cannot bear the treatment expenses (Shaheen et al., 2010). Accessing health care services in Pakistan is mostly influenced by gender roles (Bazai & Panezai, 2020; Panezai et al., 2017; Panezai et al., 2020). As men serve as heads of households, they are also supposed to have the responsibility of making decisions regarding the health needs of women as well. As a result, women's inferiority to men forces them to seek PHC services (Saqib et al., 2017). In Pakistan, about 21.7% of couples are not able to have children, and those couples who are not able to have children face a social stigma, and the pressure of their in-laws makes them very worried. Most of the time, women are blamed for not having children, but according to estimates, 60% of males are infertile. The custom of divorce and separation is due to infertility, and males always blame women for the infertility; thus, the husband goes to do the second marriage (Ali et al., 2011). Infertility is a widely existing problem among married couples in Balochistan. As Quetta is the largest and capital city of Balochistan (Bazai & Panezai, 2020), it becomes highly important to explore infertility among working women at the college level in Quetta. Besides exploring the locational differences, it is pertinent to investigate the reasons behind their infertility. The aim of this study is to find out the causes of female infertility and the treatment services availed by patients in Quetta, Balochistan.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

- This study involved a case study research design. A case study is a popular research design in the social sciences. A case study is a research method used to explore the unit or subject of study very thoroughly. In a case study, research is done with a detailed and deep examination of the subject. (Mills et al., 2009).

2.2. Study Area

- For this study, Quetta city was purposefully selected as the study area. Quetta is the largest and capital city of Balochistan Province and the 10th most populous city in Pakistan. Balochistan is the largest province of Pakistan by area with a mostly rural population (Rehman et al., 2019). The province is the least developed among all provinces in Pakistan (Ashraf, 2019). The Quetta Metropolitan is a bowl-shaped valley surrounded by mountains (Basheer et al., 2021). It is located in the southwest of Pakistan. Geographically, it is located at 30°11′38″ N, 66°57′19″ E. It has a population of 2,037,637 and is the most urbanized city in Balochistan (Bazai & Panezai, 2020). The average elevation above sea level in Quetta is about 1300 meters (5,500 feet) (Khan et al., 2020).

2.3. Data Collection

- A primary data collection method was used in the current study. A questionnaire was used in the current study. The faculty at girls’ colleges were the population. Women with infertility serving at government girls' colleges were the sample of the present study. Individual data were collected from teachers suffering from infertility at government girls' colleges in Quetta, Balochistan. The questionnaire was handed over to the participants, and it was requested that they fill it out correctly as per their knowledge and experience. The data collection was started in November 2019 and completed in June 2020.

2.4. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

- Multi-stage sampling was used in the current study. At the first stage, government girls’ colleges in Quetta, Balochistan, were selected randomly. In the second stage, a consultative meeting was conducted with staff to identify the number of teachers who were facing the infertility issue. The third stage identified respondent willingness - whether they were willing to participate in the study or not - and the final stage used universal sampling and interviewed the respondents. A total of 39 respondents who fulfilled the eligibility criteria willingly participated in the study, and none of them refused to participate.

2.5. Data Analysis and Presentation

- For the analysis of the data, the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used. Descriptive statistics techniques were used to show the frequencies and percentages of the responses, and the data was then presented in the form of tables and graphs.

3. Results

3.1. Socioeconomic Profile of Respondents

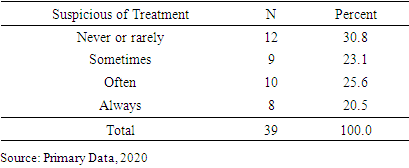

- The findings revealed that the majority of respondents (41%) were between the ages of 31 and 39, and 56.4% were from Quetta. All respondents (100%) were Muslims. It was further revealed that the duration of infertility for most of the respondents was 6–8 years. Almost two-fifths (43.6%) of the respondents were lecturers. The finding further shows that 64.1% of the respondents had M.Sc.-level qualifications. Almost half of the study sample lived with extended family. The majority (74.4%) of respondents had a good economic situation, and the majority (43.6%) had a monthly income of 100,000 or more Pakistani rupees.Figure 1 describes the victim of infertility. According to the findings, 41.0% of respondents were infertile themselves, 56.4% had infertile partners, and 2.6% were infertile and widowed.

| Figure 1. Respondents perception about their and their husbands’ infertility |

3.2. Type of Marriage

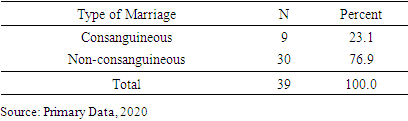

- The results in Table 1 represent types of marriages of the respondents. The data showed that 23.1% of the respondents are consanguineously married while 76.9% are non-consanguineously married.

|

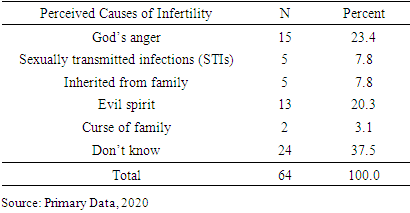

3.3. Perceived Causes of Infertility

|

|

|

|

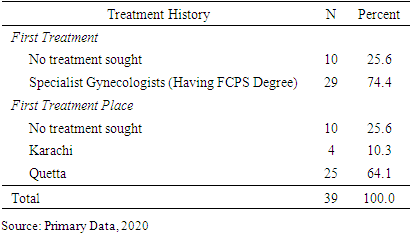

3.4. Treatment Sought by Respondents

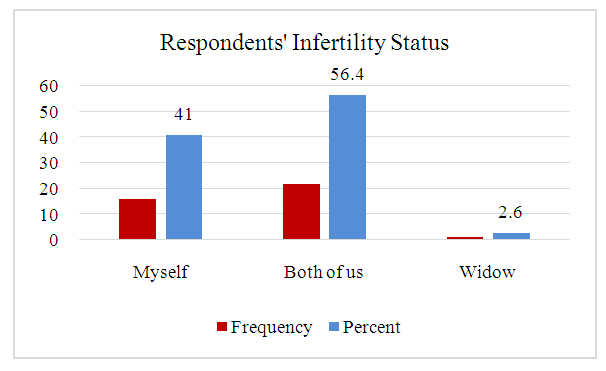

- The findings Figure 2 shows the responses on the infertility treatment sought by respondents in Quetta, Pakistan. The findings show that 64.1% of the respondents had consulted a doctor in Quetta, while the remaining 35.9% did not seek treatment.

| Figure 2. Treatment Sought by Respondents in Quetta |

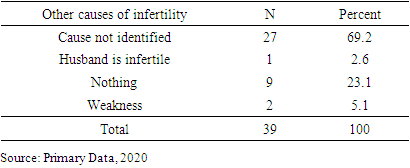

3.5. Treatment for Infertility

|

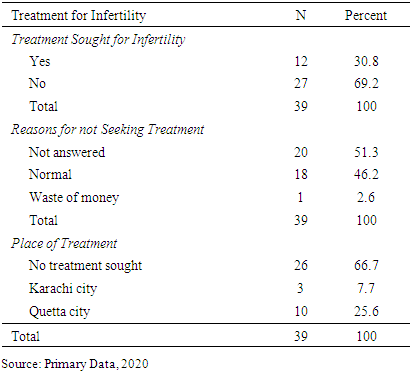

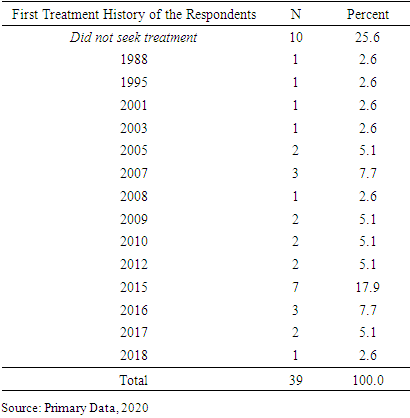

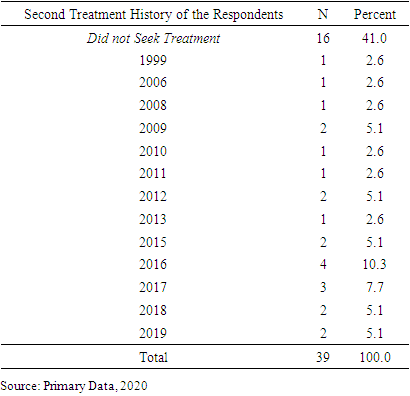

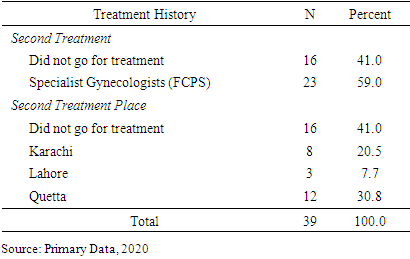

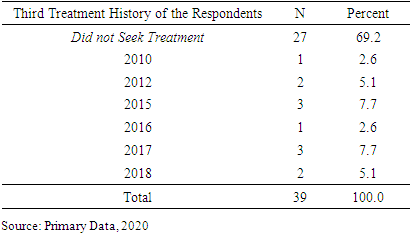

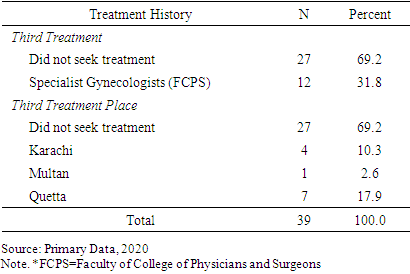

3.6. Treatment History of the Respondents

|

|

|

|

|

|

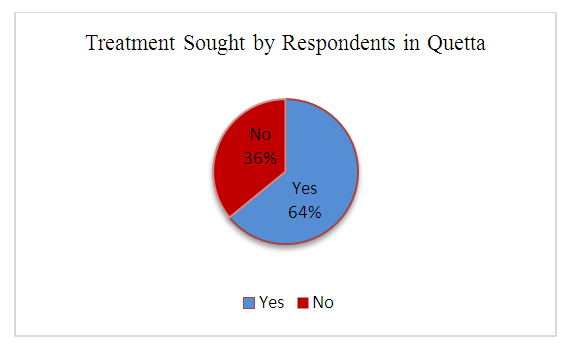

3.7. Suspicious of Infertility Treatment

|

4. Discussion

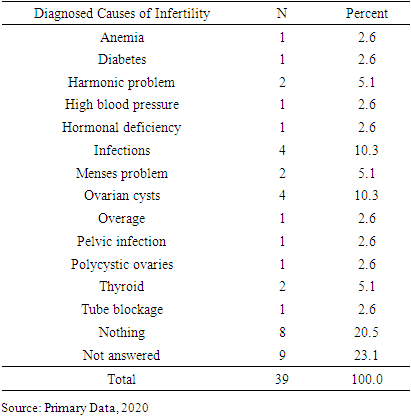

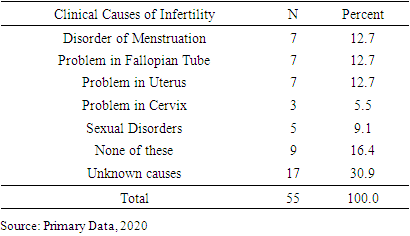

- Infertility has affected approximately 186 million people worldwide. However, infertility is high among males, and most of the infertility cases are related to men, although women are considered responsible. So the life of a female is always disturbed because people mostly think she is responsible for infertility (Inhorn & Patrizio, 2015). Married couples remain childless due to infertility, mainly due to genetic disorders, various infectious and non-infectious diseases. Infertility is now a worldwide problem (Boivin et al., 2007). It is a common misconception that infertility affects only women, but both men and women are equally likely to be infertile. (Deribe et al., 2007b). In Pakistan, the high cases of infertility cannot be undermined. According to studies, 22% of married couples in Pakistan experience infertility, with 4% experiencing primary infertility and approximately 18% experiencing secondary infertility. Infertility is not merely a physical and medical problem, but also a huge social stigma for women in Pakistan (Ali et al., 2011). In many societies, women are blamed for infertility, and it is considered a shame and stigma for them (Ombelet et al., 2008), and in most societies, the main purpose of life is giving birth to children (Gerrits, 2002). The current study looked at the causes of female infertility and the treatments used by patients in Quetta, Balochistan. Infertility is commonly thought to be a female problem, but men and women are equally likely to be infertile (Deribe et al., 2007a). In the same way, the finding of the current study also showed that in most of the cases both partners were infertile. In the same way, the findings of the current study also showed that in most cases, both partners were infertile. It was revealed through the findings that most of the respondents were graduates; similarly, the findings of Zoe et al. (2009) showed that a large proportion of the participants in their study were high school or college graduates.The findings of the current study revealed that in the causes of infertility, significant differences were observed. However, Ozturk et al. (2017) reported that in their study there were no significant causes of infertility observed. The respondents perceived that their main cause of infertility was God’s anger, an evil spirit, the curse of family, etc. According to the findings, ovarian cysts and infection predominate over other disorders, with 37.5% of respondents unaware of the causes. Similarly, Zoe et al. (2009) showed 53.6% of their participants had unknown causes. The findings of the current study also revealed that 12.7% of the respondents reported the issue in the fallopian tube as a clinical cause of infertility.The treatment of infertility depends on its causes. Fertility medication, a medical device, surgery, or a combination of these are generally used for the treatment of infertility (Mustafa et al., 2019). According to the literature, females with a higher educational level and income are more likely to seek treatment than those with a lower educational level and income. Because of the high cost of treatment, many couples, particularly those with low income, are forced to seek help after numerous unsuccessful physiological efforts (Zoe et al., 2009). Most of the respondents were taking treatment within Quetta. The reason for not taking any treatment was reported by the respondents, who said that they perceived being infertile as normal, while a few others thought it was just a waste of time. The study recommends strategies for infertile people to live a happy and healthy life. For this, they need medical treatment and, the support of family members, particularly the husband. Because of supportive families, every infertile female can face the problems bravely. It also fosters societal sympathy for such working women. Moreover, research studies report the poor health indicators of women's health in Balochistan (Naseem et al., 2020). This makes it important for the provincial health department to take serious steps toward improving reproductive health care services in the province. Limitation of the study: This study was conducted in the provincial capital, Quetta. The highly educated class of society, i.e., college teachers, were recruited as respondents for this study. The findings of this study may not be generalizable to the rest of the population living in urban and rural areas of the country. The results from the general population in urban and rural areas may differ from the findings of the current study.

5. Conclusions

- The current study explored the perceived and clinical causes of infertility among females in Balochistan. The findings revealed that the perceived causes of infertility were God's anger, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), inherited infertility from family, an evil spirit, and the curse of the family. The women in Balochistan are not well aware of the infertility issues. The majority believe that this issue is due to God's will, God's anger, an evil spirit, etc. Moreover, menstrual disorders, problems in the fallopian tube, uterus, cervix, and sexual disorders were the clinical causes of infertility. This study also revealed the healthcare seeking behavior of infertile women. Furthermore, the findings also revealed the venues from where the treatment had been sought by the patients. Most infertility patients perceive that the clinical treatment of infertility is just a waste of time and money. The study suggests that the government needs to incorporate the perceived causes of infertility into their treatment strategies. This study also suggests that policymakers and health care managers make awareness sessions and campaigns part of the health care delivery system at the provincial level for the dissemination of information regarding the clinical causes of infertility in women and encourage them to go for medical treatment as well. Moreover, at the primary health care level, a referral system needs to be established for infertile couples, so that they are advised and encouraged to seek medical care at tertiary care hospitals. The study recommends that future research be conducted by taking samples from the general urban and rural populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors acknowledge the support of teachers who provided their personal data for this study and help is data collection.

Declarations

- Funding: This research received no external funding.Conflicts of Interest: No conflict of interest.Confidentiality: In this study, the confidentiality of participants was completely ensured by keeping their names anonymous.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML