-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2018; 6(3): 52-58

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20180603.03

Hepatitis B and C Co-Infection among HIV Pregnant Women and Fetal Outcome in Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, Plateau State

Oga EO1, Egbodo CO2, Oyebode T.2

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Dalhatu Araf Specialist Hospital, Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Oga EO, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Dalhatu Araf Specialist Hospital, Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

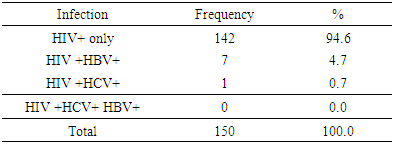

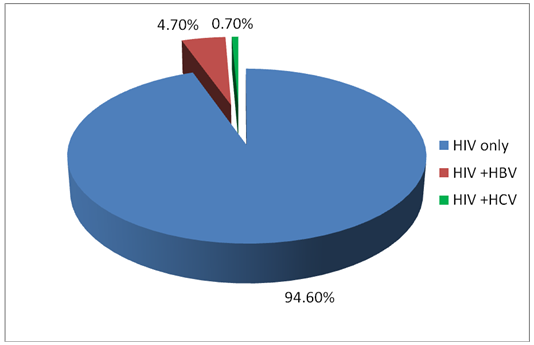

BACKGROUND: The shared route of transmission could suggest that many HIV positive clients may also be at risk of HBV and HCV infections. HIV co infection with HBV and or HCV may further worsen the outcome for the mother of the infant with a more rapid clinical and immunological progression. The magnitude of this impact of HIV co infection with HBV and or HCV on pregnancy outcome is an important topic of research. Objectives: The aim of the study is to determine the magnitude of Hepatitis B and C co-infection among HIV positive pregnant women and fetal outcome in JUTH. Methods: A longitudinal study was carried out among 150 HIV positive pregnant women seen at the PMTCT clinics of Jos University Teaching Hospital. The women were screened for hepatitis B and C virus infection at enrollment, CD4 count levels were also determined. The women were followed up to delivery to evaluate the pregnancy outcome. All relevant data including the socio-demographic information, obstetric history, past medical history and the viral hepatitis results, CD4 counts levels, and pregnancy outcome were collected and analysed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 20. Chicago Illinois. Results: Of the 150 studied subjects, 7(4.7%) and 1(.7%) respectively were seropositive for hepatitis B and C virus infection. There was no maternal nor neonatal death. No woman had triple infections. 137(91.3%) pregnant women were followed up to delivery for birth outcome. Conclusion: Hepatitis B virus infection (4.7%) is relatively common in our environment. Hepatitis C virus infection (0.7%) is however less common. There is no difference in birth outcome between women on HAART with HIV/HBV and HIV/HCV co infection and other women.

Keywords: Hepatitis B and C among HIV pregnant women in Jos

Cite this paper: Oga EO, Egbodo CO, Oyebode T., Hepatitis B and C Co-Infection among HIV Pregnant Women and Fetal Outcome in Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, Plateau State, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2018, pp. 52-58. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20180603.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C virus (HBV, HCV) are three of the most common blood-borne infections and are a major public health problem in the Sub-Sahara Africa and globally. Collectively, they cause significant morbidity and mortality from chronic liver diseases, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and opportunistic infections among infected individuals [1-5]. HIV infected persons are disproportionately affected by viral hepatitis.Hepatitis simply refers to inflammation of the liver. HBV and HCV infection primarily affects the liver and is usually symptomless for decades. If untreated, the virus causes considerable damage to the liver that can lead to cirrhosis, liver cancer and death. HIV modifies the natural history of HCV and HBV disease among co-infected individuals; They are more likely to develop chronic hepatitis [10] and have an increased risk of liver-related mortality and morbidity and suffer life-threatening complication beyond those caused by either infection alone [11, 12].Within the obstetric population, HBV, HCV and HIV co-infections also affect a significant number of pregnant women. In the absence of contaminated blood transfusions, sexual transmission and intravenous drug use, a substantial proportion of all chronic HBV cases worldwide are attributed to perinatal transmission of HBV. In spite of vaccine availability, infected pregnant women remain an important source for HBV chronic infection as children who acquire the infection at birth through mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) have up to a 90% risk of becoming chronic cases themselves [1]. Therefore, the CDC recommends routine screening for HBV at the time of the first prenatal visit with each pregnancy regardless of vaccination or previous testing [1].On the contrary, there is no current vaccine for HCV and maternal screening during prenatal visits is risk-based and not universal. Similar to HBV, MTCT of HCV is a major source of new infections among young children and 80% of perinatal cases that [5] remain HCV RNA-positive after age three develop into chronic HCV cases [2, 3]. In HIV infected pregnant women, maternal co-infection with viral hepatitis facilitates the transmission of HBV or HCV to newborns 39-42 and children born to co-infected mothers have an increased risk of progressing to chronic forms of the disease. Hence, the management of HBV and HCV disease during pregnancy, especially among HIV positive mothers who are co-infected with viral hepatitis remain an important public health issue as reducing perinatal transmission of these diseases is crucial to reducing the global burden of these diseases 5,6. HIV co-infection with HCV and or HBV further worsens the outcome for the mother and the infant with a more rapid clinical and immunological progression. [18, 19] Vertical transmission of HIV from infected mother to her child is increased by 4 to 5 fold with HCV and or HBV while the odds of vertical HCV transmission are 90% higher for women co-infected with HIV than those infected with HCV alone. HBV and HCV are also independent risk factors for hepatotoxicity with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). [18, 19] The shared route of transmission could suggest that many HIV positive clients may also be at risk of HBV and HCV infection. The non-specificity of clinical presentation and the chronic course often makes early diagnosis of HBV and HCV difficult. [18, 19] There may therefore be a hidden epidemic of HBV and HCV among PLWHA which remain undocumented and no intervention planned to manage it. It is therefore imperative to investigate the proportion and magnitude of Hepatitis B and C co-infection among HIV positive pregnant women and fetal outcome in JUTH in order to understand the magnitude of the problem and design interventions aimed at prevention and treatment in view of its growing public health significance. Hence this study will provide a window of opportunity for patient education and behavioural modification through counselling and improved management of our HCV and or HBV co-infection in HIV positive pregnant women for better pregnancy outcome.

2. Method and Materials

- It was a longitudinal study carried out in the maternity unit of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH) among the HIV positive pregnant women attending antenatal clinics at the Jos University Teaching Hospital between February 2015 to 31st January 2016. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical & Scientific Research Committee of Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos.Consecutive HIV positive pregnant women presenting to the ante-natal clinic of JUTH who satisfied the inclusion criteria and consented were recruited. A total of 150 HIV positive pregnant women were recruited. Group counseling was conducted for the study. The purpose of the study was explained and the procedure for the venepuncture and the little discomfort they might experience was explained to all subjects. Provider Initiated Counseling and Testing (PITC) was carried out. HIV screening is usually offered routinely to all pregnant women by the AIDS Preventive Initiative in Nigeria (APIN) in the hospital, with the option to opt-out. The test is usually done after pre-test counseling by the midwives who are trained HIV Counseling and Testing (HCT) counselors and the laboratory staff of JUTH. Those that consent have the screening test done free of charge by APIN centre in the hospital. APIN laboratory staff made use of serological techniques using Enzyme linked Immunosorbent assay technique (ELISA) and or western blot to determine the HIV status of the women. HIV positive pregnant women who presented to the antenatal clinic with evidence of their status were incorporated into the study.The determination of HBsAg and C was paid for by the researcher. A structured investigator administered questionnaire was administered directly to each subject. Completed questionnaires were kept confidential and the data entered into a database specifically designed for the project. Blood samples were collected aseptically by venepuncture from the eligible HIV positive pregnant women who presents in the antenatal clinic of Jos University Teaching Hospital using 5ml sterile disposable hypodermic syringes and needles. The blood samples collected was dispensed into pre-labeled specimen bottles. Specimen containers were coded to ensure confidentiality.The samples were allowed to clot and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5mins to separate the serum. The sera was extracted using micropipette and testing carried out as explained below. This was done at the Immunology Laboratory of the Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos.Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) detection was done using the in vitro diagnostic kit manufactured by ACON Laboratories, Inc. 4108 Sorrento Valley Blvd., San Diego, CA 92121, USA. The test kit (dipsticks) is a rapid immunochromatographic assay designed for qualitative determination of HBsAg in human serum or plasma. The assays were carried out at room temperature. The test strips were removed from their foil pouches and immersed into serum samples with arrows pointing towards the samples. The strips were taken out after about 10secs and placed on a clean, dry, non-absorbent surface. This was to allow time for the reaction to take place. The specimen was absorbed into the test strips and moved by capillary action upward towards the control line. The result was read after 10mins post immersion. Positive samples generated a colour band in the test (T) region of the strips and another in the control (C) region while negative samples had a colour band in the control (C) regions only.THE HCV test: It was performed using a third generation Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Biotech Laboratories, UK). According to the manufacturer's Instructions Specimen diluents (100μl) were pippeted into all test wells leaving 5 wells for control and blank. Negative control (100μl) were pippeted into duplicate wells that contain no diluents. Positive control (100μl) was pippeted into duplicate wells that contain no diluents. Specimen diluents (100μl) was pippeted into the first well and was left as blank. Test samples (100μl) were added in assigned wells and mixed. The plates were sealed and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Each well was washed 5 times by filling each well with diluted wash buffer, then the plates were inverted vigorously to get water out and blocking the rim of wells on absorbent paper for 30 seconds. Enzyme conjugate (Horseraddish peroxides) (100μl) was added to each well except the blank and was mixed by swirling the microtitre plates. The plates were sealed and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. The plates were washed 5 times. Substrate solution (100μl) was pippeted to each well and was incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. Stopping solution (50μl) was added to each well to stop the colour reaction. The intensity of the reaction was photometrically quantitated with a dual filter Enzyme Immuno Assay Reader (Sigma diagnostics EIA Multi-well Reader 11) immediately using 0.0 at 450nm, 630nm. Both HIV seropositive and HIV/HCV co-infected women were counselled on risk reduction strategies through behavioural change modification. They continued to access the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services and the need for delivery in JUTH was emphasized to them. HCV positive clients were also scheduled to be seen at the adult antiretroviral clinic after delivery for further assessment and possible initiation of treatment for HCV infection.

3. Data Analysis

- The filled questionnaires were checked for completeness and accuracy before entry. The data was analyzed using statistical package for social science SPSS version 20. (Chicago, Illinois). The data was presented as HBV, HCV and HIV co-infection. Categorical data like maternal socio-demographic characteristics was summarized using simple frequency tables. Dependent variables considered in this study were HBV/HIV, HCV/HIV and HBV/HCV/HIV co-infection status of subjects.Independent variables whose level or strength of association was determined the socio-economic characteristics, past medical and social history as indicated in the research instrument. The chi-square test of independence was used to determine association between categorical variables. Students ‘t’ test was used to compare group means. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The women were followed up to delivery where the following perinatal outcome were noted. The outcome of interest in the study were gestational age at delivery, birth weight, placenta weight, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

4. Results

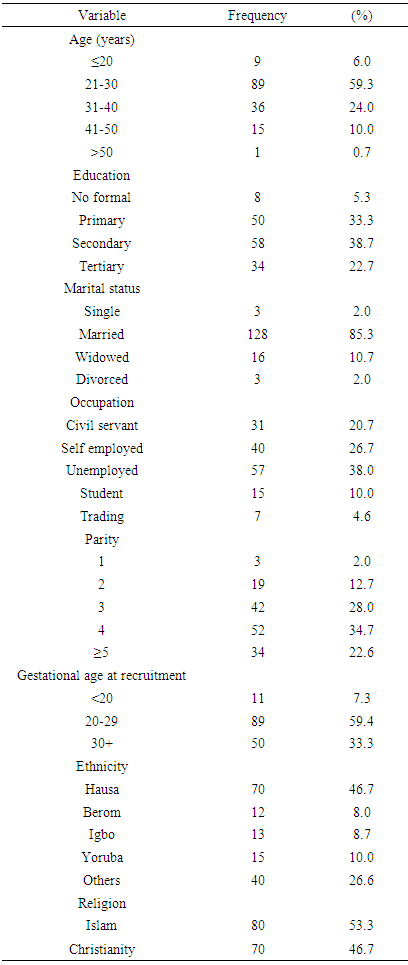

- A total of one hundred and fifty HIV positive pregnant women were recruited from the entire four hundred and eighty two (482) HIV positive pregnant women currently on care at the Jos University Teaching Hospital (PMTCT) clinic. Out of the total number of women recruited, 137 were followed-up to delivery giving a response/completion a rate of 91.3%.There was no maternal nor neonatal deaths recorded.Results

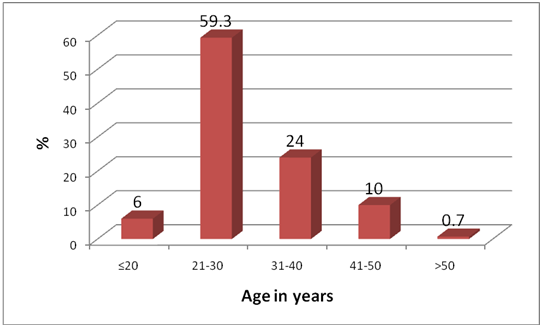

| Figure 1. Age Distribution of Study Participants |

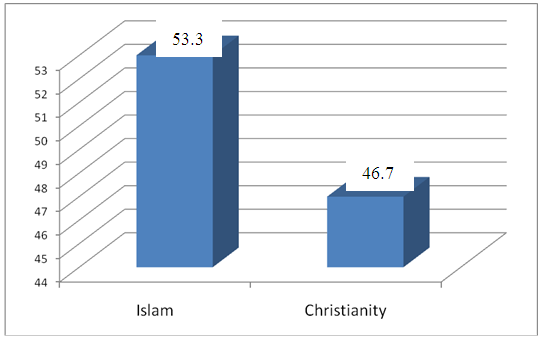

| Figure 2. Distribution of study participants according to religion |

| Figure 3. Hepatitis B, C and HIV infection combination |

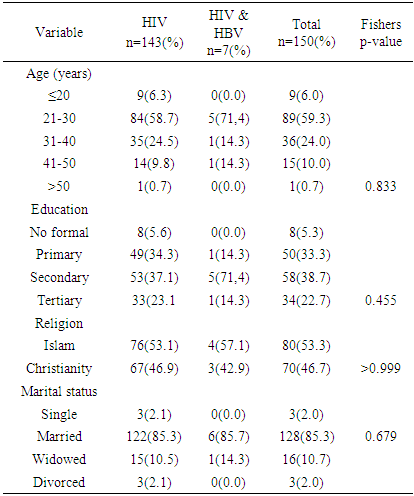

|

|

|

|

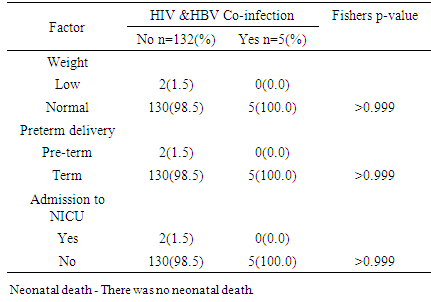

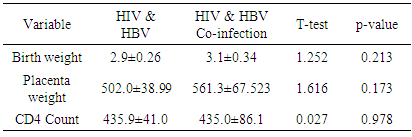

There was no significant difference in mean birth weight and placenta weight in the two groups.There was no statistical difference in CD4 count.

There was no significant difference in mean birth weight and placenta weight in the two groups.There was no statistical difference in CD4 count.5. Discussion

- The study showed a prevalence of 4.7% HBV/HIV co-infection among pregnant women attending antenatal care service at the PMTCT clinics of JUTH Jos, North Central, Nigeria. This was similar to the prevalence of 4.2% by Ezechi OC and colleagues in Lagos South-West Nigeria and Eke and colleagues in Nnewi South East, Nigeria and 4.1% by Pirrillo and colleagues from Rwanda [17-19]. Landes and colleagues in the European collaborative study reported a similar prevalence of 4.9% [20]. A likely explanation for this is that HbsAg positivity was associated with black African origin of whom accounted for one fifth (1/5) of their study population [20]. However, Adesina et al, from Ibadan, Nigeria and Rouet et al, from Abidjan, Cote d’ivoire reported higher prevalence of 8.9 and 9.0% respectively [21, 22]. A likely explanation to this variation in the prevalence rate could be the differences in social and cultural practices as well as varying sample size, test kit, sensitivity and specificity [23]. However, a lower prevalence of 1.5% was reported by Santiago Munoz et al from Texas, USA which can be explained by North American being a low endemicity area for Hepatitus B [24]. Co-infection with HIV has been found to worsen hepatitis B & C infection and progression [29, 30]. However, the effects of HBV and HCV directly on HIV disease progression remains controversial [29, 30].The study did not find any association between maternal age, education, religion and marital status with HIV/ HBV co-infection. This is however different from studies in Europe and South-Eastern Nigerian where women aged between 25-29 years and 20-30 years respectively were found to be at a significant risk of HIV/HBV co-infection [20, 23]. This could be attributed to the higher prevalence of HIV as well as the likelihood of high sexual activity in these age groups [23]. It may suffice to add, co-infection with hepatitis B increases the risk of hepatotoxicity from antiretroviral therapy at least 3-5 fold and can pose challenges to treatment modalities [24]. Hepatitis C appears to be of lower prevalence than hepatitis B in our setting but does share similar modes of transmission as hepatitis B & HIV [17]. The prevalence of HCV/HIV co-infection in this study was 0.7%. This compares with the 1.5% by Ezechi OC & colleagues from Lagos, south West Nigeria, 1.5% by Adesina et al from Ibadan, 1.0% by Route et al from Abidjan and 1.3% by Simpore et al from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso [17, 21, 22, 27]. Higher prevalence of 4.9% and 12.3% in Texas, USA and Europe were reported by Santiago-Munoz et al and Landes et al from Europe and was attributed to intravenous drug use in these populations [20, 24]. Presently, intravenous drug use is not a major challenge in our environment thus may have accounted for the lower prevalence. Although, the effect of HBV and HCV infection on HIV disease progression remains controversial, it has been suggested that co-infection between hepatitis C virus and HIV may be associated with a rapid decline in the CD4 count, rapid progression of HIV infection and increased morbidity and mortality [28].From the study, nobody had triple infections of HBV, HCV and HIV, however, Ezechi OC and Colleagues from Lagos, South West Nigeria reported a prevalence of 0.08% with triple infections of HBV, HCV and HIV [17]. Also reported was 0.1% with triple infections of HBV, HCV and HIV at Ibadan, South West Nigeria suggesting that all 3 co-infections in pregnant women is uncommon in our settings [21]. From the study a total of 137 (91.3%) women out of the 150 that participated were followed up until delivery while 13 (8.7%) women were lost to follow-up. There was no significant difference in birth outcomes in terms of birth weight, preterm delivery placenta weight and admission into NICU between women with HIV/HBV co-infection and other women. There was no neonatal death. This is similar to the findings by Connell LE and colleagues from Florida USA, Tseky and colleagues from Queen Mary hospital Hong-Kong, Lobstein S and colleagues from Eastern part of Germany and Wong S and Colleagues from Hong Kong, China. This could be explained by the long standing use and compliance to HAART therapy. Immunological explanation is that most adults infected HBV are able to clear their infection spontaneously, resulting in lifelong protective immunity [30].

6. Conclusions

- Even with the high prevalence of 4.7% for HBV and 0.7% for HCV in this study, there was no significant association between HBV and HIV co infected pregnant women on HAART and adverse pregnancy outcome. Emphasis, however, must be on routine screening of all pregnant women for HBV and HCV with prompt referral and treatment to reduce perinatal transmission.

7. Recommendations

- Besides the routine antenatal HbsAg and hepatitis C antibody as markers for screening for HBV and HCV respectively, positive patients should always be evaluated further on other serum markers of hepatitis B, in order to ascertain the serological evidence of active or past infection or prior immunization for HBV.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML