-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2018; 6(3): 41-46

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20180603.01

Profile of Risk Factors in Relation to the Outcome of Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) among Pregnant Women in Jos University Teaching Hospital (Juth), Jos

Oga EO1, Egbodo CO2, Lucius CI3

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Dalhatu Araf Specialist Hospital, Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

3Department of Chemical Pathology, Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Oga EO, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Dalhatu Araf Specialist Hospital, Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

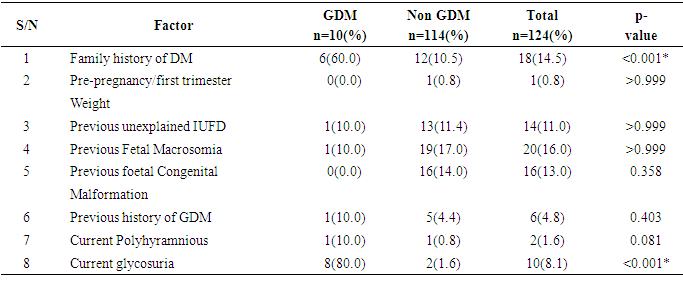

Background: Several risk factors have been identified as contributing to the development of gestational diabetes mellitus. Knowing and ranking these risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus will provide useful information for health care providers in educating women on the need to reduce the risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus. Objectives: The aim of the study is to determine the profile of risk factors in relation tothe outcome of screening for gestational diabetes mellitus. Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out among 130 pregnant women enrolledfrom the antenatal clinic of Jos University Teaching Hospital JUTH. Using a convenient sampling method, screening was done between 24-32 weeks gestation using the 75g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Gestational diabetes mellitus was diagnosed according to WHO criteria. All relevant data including the socio demographic information, obstetric history, past medical history and risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus, OGTT results were collected and analyzed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 20 Chicago Illinois. Results: Of 130 pregnant women enrolled, 124 subjects were eligible for screening outof which 10(8.1%) had gestational diabetes mellitus giving a prevalence of 8.1%. The pattern of glucose tolerance in the study population indicated that 114(91.9%) had normal glucose tolerance. In the study population current glycosuria and positive family history of diabetes milletus were the most common risk factors for GDM in order of ranking. Conclusion: The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus was relatively high amongour antenatal population. Women with current glycosuria and positive family history of diabetes have higher likelihood of having gestational diabetes mellitus and should be screened.

Keywords: Risk factors, GDM, OGTT, Pregnancy, JUTH

Cite this paper: Oga EO, Egbodo CO, Lucius CI, Profile of Risk Factors in Relation to the Outcome of Screening for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) among Pregnant Women in Jos University Teaching Hospital (Juth), Jos, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2018, pp. 41-46. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20180603.01.

1. Introduction

- Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is defined as any degree of impaired glucose tolerance first recognised during pregnancy, and a reversal to normal glucose metabolism after delivery. [1, 2] This includes women who first present with type 1 or type 2 diabetes during pregnancy or where diabetes was previously undetected. It is the commonest form of hyperglycaemic disorder in pregnancy. [3] The glucose intolerance of GDM is usually mild, but nevertheless it means a higher incidence of complications during pregnancy [3] and, in some cases, an increased perinatal mortality and morbidity of the infants. [4] As well, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus also considerably increases the woman's risk of developing frank diabetes mellitus later in life. [4, 5] Thus, it is important to recognize and to treat this disease. Gestational diabetes mellitus is of interest in obstetric practice because of its significant association with many obstetric and metabolic complications resulting in morbidity and mortality of pregnant women and infants. These include pre-eclampsia, placental anomalies, intra-uterine foetal death and increased caesarean section rates in the mother as well as hypo glycaemia, hyperbilirubinaemia and respiratory distress syndrome of the newborn. [3, 4] Gestational diabetes mellitus complicates about 4% of all pregnancies worldwide. In Nigeria, the prevalence is between 0.29% and 2.9% of pregnant women. [7, 8] Gestational diabetes mellitus occurs more frequently in older, obese women [9]. Indeed the incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus is thought to be increasing globally as a result of increase in the prevalence of obesity and T2DM. [6]Gestational diabetes mellitus usually occurs between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation as a result of increased insulin resistance in the second trimester. [7] The glucose levels rise in women who are unable to produce enough insulin to adapt to the increased insulin resistance. [8]Risk factors for screening of gestational diabetes mellitus include previous history of unexplained intra-uterine foetal death (IUFD), previous foetal macrosomia, previous history of gestational diabetes mellitus and gross foetal malformations. [8, 9] Increasing maternal age, family history of diabetes and overweight are also risk factors for gestational diabetes as well as pregnant women with current polyhydramnios and glycosuria. There are considerable variations in the screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus, when to screen and to whom it should be applied. [15] Universal and risk factor-based screening has been advocated but advocates of universal screening claim that one-third to half of women with gestational diabetes mellitus will be missed if traditional risk factors are used for screening gestational diabetes mellitus. [16] Currently gestational diabetes mellitus is diagnosed using either two- or one-step method involving initial screening procedure or direct application of the diagnostic 75 or 100 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Diagnosis is based on American Diabetes Association (ADA) or World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria. [17] Several risk factors have been identified as contributing to the development of gestational diabetes mellitus. There is however paucity of data regarding the proportion of pregnant women with the traditional risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus who actually manifested with gestational diabetes mellitus; thus the rationale for this study. Also it will be of interest to determine the proportion of pregnant women in our environment with gestational diabetes mellitus who had risk factors and those without risk factors. The outcome of this study will assist in policy formulation regarding the inclusion or otherwise of routine screening for diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus.

2. Methods and Materials

- It was a cross-sectional study among 130 pregnant women with gestational age ≤32 weeks who met the study criteria and enrolled for antenatal care between 1st August to 31st October 2015 at Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical and scientific research committee of the hospital.Study ProtocolThe data was collected using the questionnaires formed by the researcher and the results of laboratory tests done on the participants. This was done at the antenatal clinic after obtaining consent from the participants to participate in the study.ProcedureAt the antenatal attendance, the subjects were interviewed by the researcher with a pre-designed proforma. The following information were recorded; age, parity, gestational age, last child birth, level of education, occupation, presence of risk factors for the development of GDM such as family history of diabetes mellitus in first degree relative, history of big babies (weight >4.0kg), history of still birth and the pre-pregnancy weight or first trimester weight and height of the participants were also taken and assessed for obesity (BMI ≥30kg/m2).The participants were told in details regarding the procedure for the screening test. Women with gestational age less than 32 weeks were booked for OGTT between 24-32 weeks of gestation. At 24-32 weeks of gestation, consenting women for the study were enrolled for a 2 hour OGTT. About 3mls of venous blood was collected in a plain bottle from the antecubital fossa with strict adherence to antiseptic procedure and another 3mls of venous blood was collected after 2 hours time point after the 75g glucose load, each subject sample bottle were labelled with name and hospital number to aid identification.The diagnosis of GDM was made according to WHO criteria (0 hour glucose ≥ 7.0mm/L and/or 2 hour glucose ≥ 7.8mmol/L).Patient Preparation75g oral glucose tolerance test:• The subjects ate their normal diet for at least three (3) days before the test.• The women were told to abstain from alcohol and tobacco use during the test.• The women fasted for 10-12 hours but not more than 16 hours before the test.• Only water intake was allowed during the fasting and the test periods.• The women rested quietly during the procedure.Specimen Collection and ProcessingThe laboratory test was done at the Chemical Pathology laboratory of the hospital under the supervision of the consultant. The glucose loads were weighed using Tripple beam balance 700 series 2610g capacity and the plasma glucose measurements was performed with spectrophotometer (SPECTRO B-16 wave 546nm) using glucose oxidase method.Analysis of Blood SamplesBlood samples were analysed for glucose by automated colorimetric enzymatic anlaysis using Cobas (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Sandhofer Strasse 116, Mannheim, Germany) commercial kits on the Roche/Hitachi 902 automatic analyzer (Hitachi High-Technology Corporation, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8717, Japan).Blood Sample CollectionAbout 3mls of Blood specimen was collected from a peripheral vein (antecubital venopuncture) with strict adherence to antiseptic procedure and transferred into a bottle containing sodium fluoride (6mg per ml whole blood). It was allowed to cloth for 30minutes and immediately centrifuged at 4000rpm for 5 minutes to separate the serum; for glucose analysis. The glucose was analysed within 1 hr after collection of samples.Quality ControlAnalytical accuracy and precision was assured by simultaneous analyses of pooled serum and commercial quality control specimen, at low and high control ranges from (COBAS Roche Diagnostic, D-68305 Mannheim, Germany with each batch of samples.Statistical AnalysisThe filled questionnaires were checked for completeness and accuracy before entry. Analysis was done using statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 20. Data presentation was done using tables, charts, and diagrams. Quantitative variables were summarized using measure of central tendency and dispersion as appropriate.

3. Results

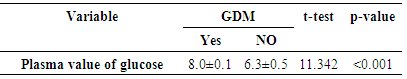

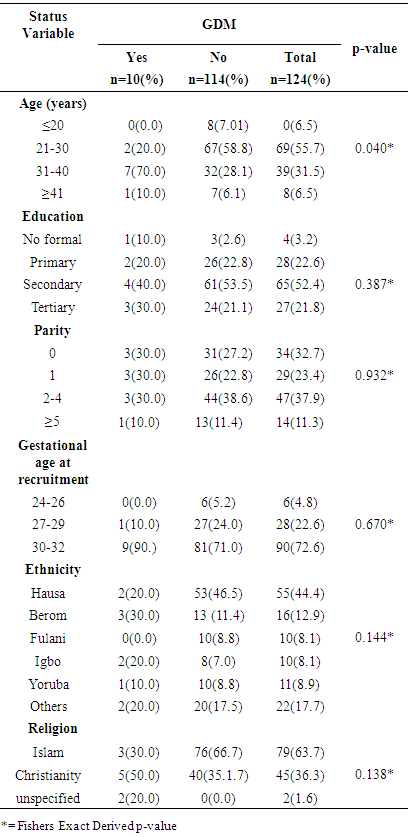

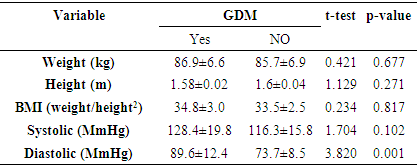

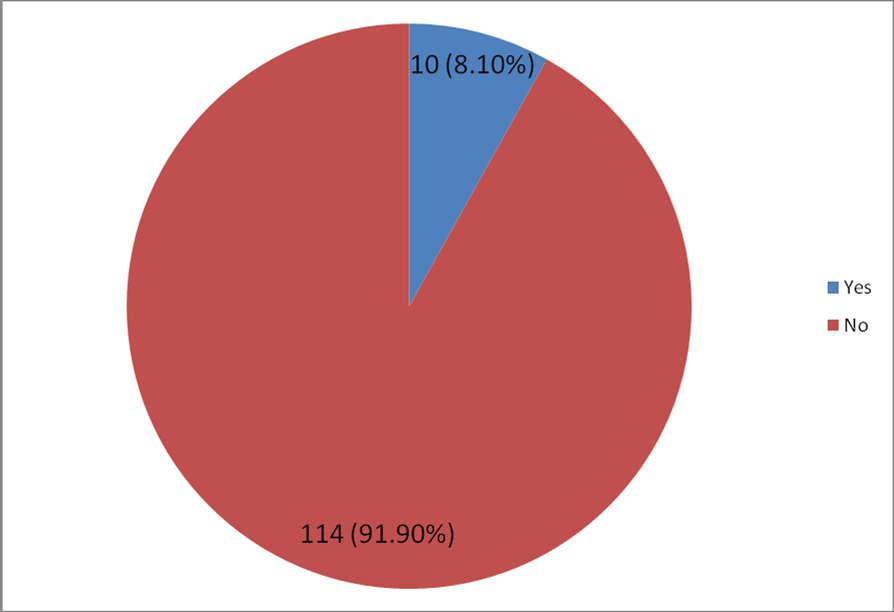

- A total of one hundred and thirty (130) pregnant women were recruited from the Antenatal Care Unit of JUTH over the study period. However, one hundred and twenty four (124) participated fully giving a response rate of 95.4%. Among the 124 pregnant women screened for GDM, 10 had GDM giving a prevalence of 8.1% (figure 1). The pattern of glucose tolerance in the study population indicated that 114(91.9%) had normal glucose-tolerance.

| Figure 1. Distribution of Subjects According to GDM Status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

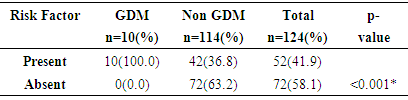

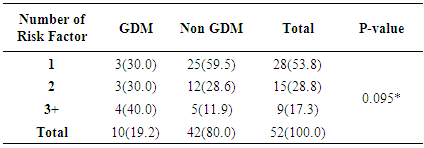

- The study showed a prevalence of 8.1% gestational diabetes mellitus among antenatal population of Jos University Teaching Hospital Jos, Nigeria. This is far higher than earlier study in Nigeria which found the prevalence of 4.5% of gestational diabetes mellitus using NDDG criteria in Lagos. [9]The prevalence found in this study approaches 11.6% gestational diabetes mellitus found by authors who studied antenatal population in Lagos, South-western Nigeria using the same WHO criteria. [9] This is in keeping with the assertion that the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus is influenced by the diagnostic method and the study population [8, 21] which in this study consisted of pregnant women from diverse ethnic groups. The Lagos study like this study used the 75g OGTT for diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus which has a better sensitivity and more likely to detect more cases of gestational diabetes mellitus.The prevalence found in this study is similar to the 8.3% gestational diabetes mellitus found by a previous study in Jos-Nigeria but different methodology where a screening procedure (GCT) was firstly done before subjecting those positive to a confirmatory 75g OGTT for diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. [29] Also Hausa ethnic group was the predominant group just like this study (44.4%) and the high prevalence could be explained by the fact that in both study over one-third of those with gestational diabetes mellitus were multiparous. Studies have shown that increasing parity is at risk of medical complications in pregnancy including gestational diabetes mellitus. [24, 25, 33] Ugboma et al got a prevalence of 6.8% which could be explained by the inclusion of women at later gestational age for; testing from sixteen to thirty four weeks of gestation. [28] Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus increases with advancing gestation because of increase glucose intolerance with advancing gestation. [23] Kuti et al also had a higher prevalence of 13.9% in Ibadan, South-Western Nigeria and the study evaluated records of pregnant women who were referred to the metabolic research unit for confirmation. This methodology could be responsible for a higher prevalence reported in their study population. [14] Moses et al also had a higher prevalence of 9.5% from a study in Australia, the higher prevalence may be as a result of the difference in diagnostic criteria used. The study used the Australia-Asian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society; fasting blood sugar of 5.5mmol/L and two hours levels ≥ 8.0mmol/1 after a 75g OGTT was used [31] Ryan reported a prevalence of 17.8% from a Canadian study. [32] This high prevalence is not surprising as the IADPGS criterion was used. Studies have shown that populations that used the IADPGS criteria have prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in the range of 10-25%. [20] Others have reported a range of 12.4% - 37.7%. [31]India has been reported as the diabetes capital of the world, [26] Seshiah et al in determining the prevalence in an urban population got a value of 17.8%. [30] Direct use of the WHO 75g OGTT was done and screening was also conducted in all women irrespective of gestational age, and with a large population of type-2 diabetics, a high prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus found in the study is not surprising.United Arab Emirates, a multi-ethnic society is said to have the second highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes (approximately 20.1%). [27]The pattern of glucose tolerance in this study population was different from that reported from Ilorin, Nigeria where 34 pregnant subjects after OGTT had values of 5(14.7%), 22(64.7%) and 2(5.88%) for normal glucose tolerance, impaired glucose tolerance and overt diabetes respectively. [34] The methodology used in the Ilorin study included the use of 100g OGTT. Additionally, the study population comprised those suspected of having gestational diabetes mellitus and were referred to the metabolic clinic for confirmation. This methodology could also be responsible for the prevalence reported in their study population when compared to the prevalence found in this study. However, the pattern of glucose tolerance in this study population is similar to the one reported in Lagos where 88.7% of the women were found to have normal glucose tolerance. [9]From the study, all the pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus (100%) had at least a risk factor for gestational diabetes mellitus while 37% of women without gestational diabetes mellitus had a least one of the traditional risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus and of these, previous fetal macrosomia was commonest (16.0%). While current glycosuria (80%) and positive family history of diabetes mellitus (60%) were the commonest risk factors in the GDM group. This is similar to that reported from Lagos with a previous history of fetal macrosomia (16.9%). [9] However, Kuti et al in their study showed that positive family history of DM and a history of gestational diabetes mellitus previously contributed significantly to the risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus. [14]

5. Conclusions

- The prevalence of GDM was relatively high among our antenatal population. Women with current glycosuria and positive family history of diabetes have higher likelihood of having GDM and should be screened. From this study, the proportion of non-GDM women with the conventional risk factors for GDM is not statistically significant, hence the risk-based screening is favoured as opposed to the universal proposed by FIGO.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML