-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2018; 6(1): 9-15

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20180601.02

Active Management of Third Stage of Labor: Knowledge and Practice among Non Physician Obstetric Care-Givers in Primary Health Care Setting in Calabar Municipality, South-South Nigeria

Udeme Asibong1, Ubong Akpan2, Essien Ayi3

1Department of Family Medicine, University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria

3Department of Biology, Faculty of Education, University of Calabar Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Ubong Akpan, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Calabar, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

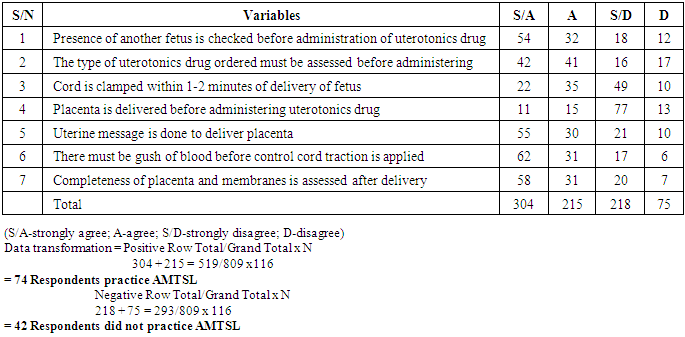

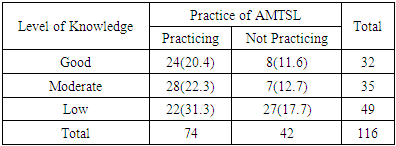

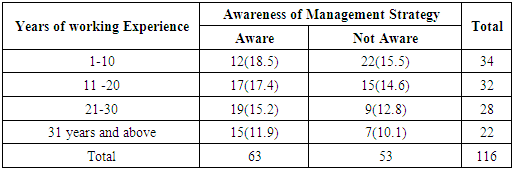

Postpartum hemorrhage remains the leading cause of maternal death in sub-Saharan Africa. Active management of the third stage of labor (AMTSL) compared with passive management has significantly reduced the incidence of post-partum hemorrhage (PPH) in health facilities. Thus the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) and International Conference of Midwives (ICM) have adopted AMTSL as a standard protocol in maternal care. However, the knowledge and application of this protocol of management at primary health facilities need to be evaluated and hence this study. A descriptive cross-sectional interviewer-questionnaire-based survey was conducted among 116 non physician skilled birth attendants at government primary health centers in Calabar Municipal. Sixty-seven (57.8%) of the participants had satisfactory knowledge about AMTSL, while 49(42.2%) had low knowledge. Seventy-two (62.1%) of them practiced AMTSL but only 20.4% does it correctly and consistently. Major factors affecting the practice of AMTSL were inadequate knowledge, an inadequate number of trained midwives and non-availability of uterotonics drugs at the health facilities. There was statistical significant relationship between being knowledgeable and correct practice of AMTLS (calculated x2=17.9; tabulated x2=5.99; p<0.05). Also, years of practice was positively associated with good knowledge of AMTSL (calculated x2 =8.9; tabulated x2=7.815; p<0.05). More resources should be channeled to training and re-training of obstetric care providers on this important subject to improve the quality of labor management.

Keywords: Postpartum hemorrhage, Labor, Uterotonics, Maternal mortality, Awareness and practice

Cite this paper: Udeme Asibong, Ubong Akpan, Essien Ayi, Active Management of Third Stage of Labor: Knowledge and Practice among Non Physician Obstetric Care-Givers in Primary Health Care Setting in Calabar Municipality, South-South Nigeria, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2018, pp. 9-15. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20180601.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The third stage of labor refers to the period following delivery of the baby until complete delivery of the placenta. The international federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) and International Conference of Midwives (ICM) define active management of third stage of labor (AMTSL) as the use of uterotonics immediately following delivery of the fetus (within one minute), controlled cord traction and uterine fundal massage immediately after delivery of placenta and membranes (FIGO/ICM, 2003). Physiological or expectant management of the third stage of labor involves waiting for the signs of placental separation and spontaneous delivery of the placenta aided by the gravity or maternal effort and uterine massage after the delivery of the placenta when necessary (Prendiville et al, 2004; Begley et al 2011). In practice this stage of labor commences with the complete delivery of the fetus and ends with complete delivery of placenta, the length of the third stage itself is usually 5-15 minutes, but the actual time suggested by World Health Organization (WHO) in 2012 ranges from 30-60 minutes. However, recent studies suggest a higher risk of postpartum hemorrhage after 30 minutes (WHO 2012; Frolova et al, 2016).Previously, relatively little attention was devoted to the third stage of labor compared with that given to the first and second stages. But the third stage of labor may be viewed as the unpredictable moment of parturition in human because some unexpected life-threatening events may occur compared to the other stages of labor (Magann et al 2005 & 2008). Some of these complications that occur during the third stage of labor include post partum hemorrhage (PPH), retained placenta, uterine inversion, infection (sepsis), post partum shock, genital tract injury (WHO 2006 & 2007; Saltain 2008; Rogers et al 1998). The most common complication is post partum hemorrhage (PPH) which accounts for about 25% of maternal deaths due to bleeding (Kashanian et al 2010; Oyetunde et al 2015).It has been suggested that if the protocol of active management of third stage of labor (AMTSL) is fully adopted and implemented, there would be a significant reduction in the incidence of PPH, hence decreasing the number of maternal deaths (WHO 2007; Elbourne et al 2001). It is, therefore, necessary to train the obstetric care providers on AMTSL and emphasize the need for the consistent practice of AMTSL. A previous study on knowledge and challenges experienced by birth attendants in primary health care revealed that a significant proportion of them lacked sufficient knowledge and skills in managing the third stage of labor and many of them had inadequate training on conducting clean and safe delivery (Oladapo et al 2009; Tenwan et al 2016).Although, AMTSL is effective and has been widely promoted, data on the use of this practice are limited. Hence, the aim of this research was to assess the knowledge and evaluate the practice of AMTSL among skilled health attendants in government primary health centers in Calabar Municipal.HYPOTHESESHypothesis 1: There is no significant relationship between knowledge of AMTSL and practice of AMTSL among obstetric caregivers in primary health care setting in Calabar Municipality.Hypothesis 2: There was no significant relationship between obstetricians’ years of working experience and awareness of management strategy of AMTSL in primary health care setting in Calabar Municipality.

2. Methodology

- Study DesignThe study design was a cross-sectional descriptive questionnaire based survey extracting data on demographic profile, knowledge, and utilization (practice) of various components of active management of third stage of labor among obstetric care-givers in primary health care setting in Calabar municipal.Study settingThe study was conducted in Calabar municipal local government. The local government is divided into 10 wards, and in them holds primary health care centers, health posts, polyclinic and a General Hospital. The local government had 5 primary health care centers from 5wards that provide labor and delivery services. Other health services like contraception services, HIV prevention programs and immunization against childhood diseases are also carried out.Recent data on “trend in maternal mortality from 2010 to 2014” showed that Calabar recorded a maternal mortality ratio of 448 per 100,000 live birth and sixty-one (61) pregnancy-related deaths were due to obstetric hemorrhage. As high-risked pregnancy, cases/postpartum complications are often referred from government primary health centers to General and Teaching hospitals in Calabar.Calabar has an area of 40km2 and a recent population estimate of 431200 according to the Geomeris geographical database. The indigenes of Calabar are mainly of Efik and Quas extraction; however, about half of the population of Calabar is made of people from Ejagham, Ibibio, Oron, Anang, Igbos and immigrants from other tribes.Study populationThe study population which is also the sample population comprised all consenting skilled birth attendants working in the government primary health centers. Different categories of non-physician birth attendants were studied; they included nurse midwives, general nurses, community health officers and community health extension workers. The study was conducted between 1st February and 31st April 2017.Sample and sampling techniqueTotal sampling technique was used due to few numbers of respondents. One hundred and sixteen health care workers were included in the study and all of them consented to participate in the study.The tool for data collectionPre-tested interviewer-administered questionnaire developed to explore the objective of the study was used to collect data on demographic features, level of knowledge and practice of AMTSL based on FIGO guidelines. Participants were asked to mention the components of AMTSL including management strategies used on the components mentioned. They were asked how often they practiced AMTSL in the preceding 6 months. Their source of knowledge was sort. The questionnaire was divided into four sections:Section one: Social demographic variables.Section two: Obstetric care-givers knowledge on AMTSL.The assessment was based on the use of uterotonics drugs, recommended route of administration, time of administration, knowledge on the essential components of AMTSL. Participants who identified all three (3) components and time of uterotonics administration were regarded as “sufficiently knowledgeable” and those who identified less were regarded as “less knowledgeable”.Section three: Obstetric care givers practice of AMTSL. Assessment here includes: Checking presence of another fetus before administering uterotonics, the type of uterotonics drug used, application of control cord traction, performance of uterine massage and assessment of placenta and membranes after delivery. Those who answered all were regarded as those who effectively practiced AMTSL and those who answered less than four (4) were regarded as those who did not effectively practice using FIGO guideline. The correct and consistent practice was considered in those who practiced all the components of AMTSL according to FIGO/ICM guidelines consistently for the preceding 6 months.Section four: Information on factors enhancing or hindering the practice of AMTSL; questions about the hospital policy or management policy towards the adoption of active management of the third stage of labor protocols or guidelines, training or workshop attended on the subject, availability of uterotonics drugs and storage facility. Also, the years of experience and the cadre of skilled personnel during delivery were asked to determine the factors hindering the practice of AMTSL.Validity of instrumentThe tool was adapted, modified and pretested. To ensure the quality of data, all filled questionnaire, were checked for completeness and consistency before included in the analysis.Reliability of the instrument (Test-Re-Test)To determine the reliability of the instrument, the pre-test questionnaire was administered to ten non-physicians obstetric care-givers in the University of Calabar Medical Centre, the questionnaire was re-administered after one week to the same caregivers, thereafter the data obtained was computed using Pearson’s product correlation coefficient and reliability coefficient of 0.72 was obtained.Data analysisData were analyzed using SPSS version 16.0, categorical data were presented in proportion and percentages. Differences between means of variables were calculated using chi square inferential statistics to assess the significant difference between two variables, statistical significance was set at P=0.05.Ethical issuesApproval was obtained from the state ministry of health. Clearance was also obtained from the PHC coordinator at the local government headquarters. Regional heads of maternity units gave permission to conduct the study in each selected health centers. Written informed consent was obtained from each respondent before data collection. Coding was used to avoid names and other personal identification of the respondents throughout the study process to ensure participants confidentiality.

3. Results

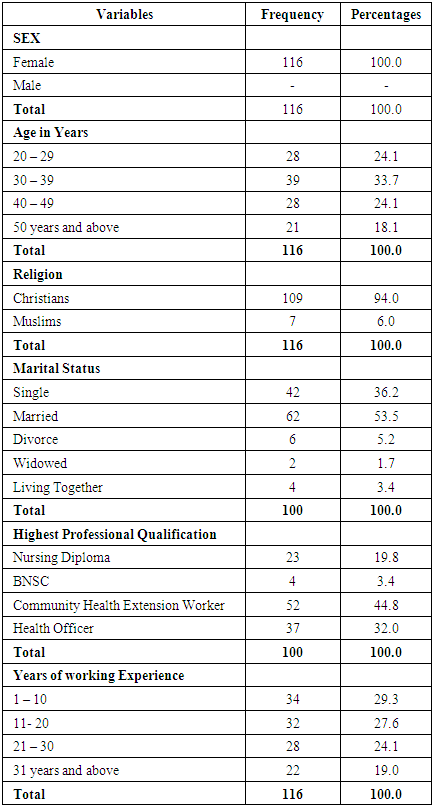

- A vast majority 39(33.7%) of the respondents were in the age group of 30 - 39 years. Among the 116 respondents enrolled for the study, 23(19.8%) had nursing diplomas, 4(3.4%) had Bachelor degree in nursing science (BNSc) as their highest professional qualification, 52(44.8%) had certificates as Community Health Extension Worker while 37(32.0%) had health officer certificates. In assessing years of service, 34 (29.3%) had 1 - 10 year of working experience. About one quarter 32(27.6%) of the respondents had years of service between 11 - 20 years, 28 (24.1%) had 21 - 30 years while 22 (19.0%) had years of working experience of 31 years and above. table 1.

|

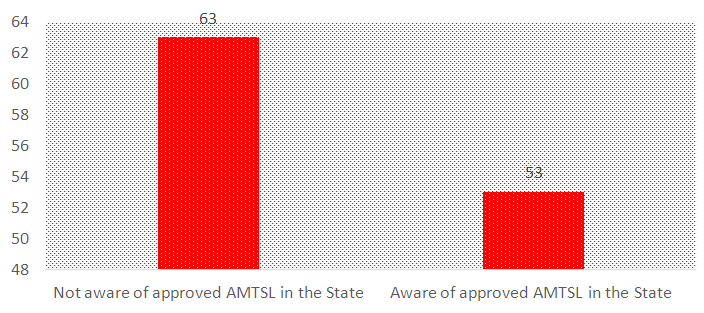

| Figure 1. Bar chart showing care-givers awareness of approved recommended AMTSL strategies in primary health care setting in Calabar Municipality |

|

|

|

4. Discussion of Study Finding

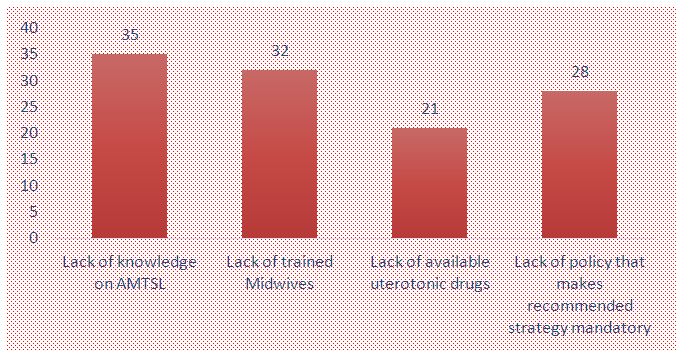

- The study was conducted among non physician skilled birth attendants in primary health centers. Of the 116 birth attendants approached all of them consented to give a response rate of 100%. The results of the study revealed that despite various intervention programs on maternal and neonatal care, much effort is still needed to promote and actualize the desired goals of safe-motherhood in many developing countries especially in the area of safe delivery.In this study, only female health workers were involved because in the setting where the study was conducted maternity units of primary health centers are often dominated by female care-givers. It is also a general observation that most male nurses in Nigeria do not go into midwifery. This is also similar to findings by Oladapo et al in their study in Western Nigeria where more than 90% of the midwives studied were females. Also in a similar study recently conducted in Eastern Nigeria, all the 177 midwives who participated in the research were females (Oyetunde & Nkwonta, 2015). Of interest to note is the limited number of qualified midwives in the various health care facilities in the state. This may be due to irregular employment exercise by the state government which over the years has led to shortage of skilled man power in the health sector. This finding suggested that lack of human resources may be a major hindrance in the State health care delivery. It is also evidenced in this study that generally the higher cadres of health professionals were more likely to possess good knowledge about AMTSL compared to those in the lower cadre (p<0.05), and this may be due to clinical experiences obtained in their various training programs over the years. Although almost all the participants claimed to have known and practiced AMTSL in their facilities, only about one third exhibited satisfactory knowledge using FIGO/ ICM guidelines. The study also showed that a good level of awareness of the approved recommended AMTSL strategies was positively associated with correct practice (p<0.05). A previous study had shown that educational attitude of the midwives was significantly associated with good practice (Oyetunde et al 2015). Those who had a good level of knowledge had four times higher odds to have a better practice than their counterparts.In assessing the timing of cord clamping about half of the respondents considered early cord clamping as beneficial. There is a controversy concerning when it is ideal for cord clamping during AMTSL. There is no existing guideline as to the right time of cord clamping. Previously early cord clamping was considered when the cord is clamped within one minute of delivery of the baby, however, evidence exists that such practice may increase incidence of neonatal anemia especially in preterm infants (Mercer et al, 2007). Furthermore, the study revealed the factors hindering the practice of AMTSL as lack of knowledge (30.2%), lack of trained personnel (27.6%). In a similar study by Tenaw et al, 2016, more than half the subjects knew all the three components of AMTSL but only 15.7% of the respondents correctly practiced it. As part of critical strategies for reducing maternal morbidity and mortality, it is important to ensure that every birth is assisted by a skilled birth attendant with requisite knowledge who can prevent life-threatening complications. Also, lack of government policy that makes recommended strategy mandatory (24.1%) which is also similar to findings from Winter et al (2007) who affirmed that not all health facilities actually adopt and practice AMTSL based on the recommended strategy by ICM/FIGO. A significant relationship existed between knowledge and its practices as well as job experience (p<0.05).This might be due to good knowledge of AMTSL enhancing their practice to prevent morbidity and mortality associated with post partum bleeding. This is similar to findings from a previous study (Oladapo et al, 2009). It is also reasonable that prolonged exposure on the job and being involved in various programs set up for health workers to be well informed and enlighten on AMTSL may be beneficial. These categories of personnel are also more likely to attend various workshops, seminars, and training regarding maternal and newborn care.

5. Conclusions

- This study has revealed the practice and limitations in implementing AMTSL protocol at the primary level of care. Among other things, lack of uterotonics drugs and inadequate number of nurse midwives are possible hindrances towards the practice of AMTSL. Hence, the need for an adequate supply of uterotonics drugs, training and retraining of birth attendants to improve their knowledge and practice of AMTSL cannot be overemphasized. The recommended protocol and guideline by ICM/FIGO should be adopted and conspicuously displayed in the delivery ward to serve as a constant reminder.

Limitation

- The study relied on information volunteered by the participants. It is possible some important facts might not have been mentioned. The low number of health workers in the maternity units of the health centers sampled makes it difficult to generalize the findings in the entire state.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We wish to acknowledge Miss Beatrice Moko for assisting in the data collection, the heads of the maternity units, and the data analyst for their immense contribution to the research.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML