-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2018; 6(1): 1-8

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20180601.01

Post Caesarean Section Wound Infection and Microbiological Pattern at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Southern Nigeria

Khadijah Olatayo Hassan, Justina Omoikhefe Alegbeleye

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH), Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Justina Omoikhefe Alegbeleye, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH), Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Caesarean section is the commonest surgery done in modern obstetric practice. As safe as this procedure may be, it is associated with varying degree of morbidities and sometimes mortality including post-operative wound infection. Wound infection is a very important cause of physical and psychological stress leading to prolonged hospital stay. Objectives: The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of post caesarean section wound infection, the common microbiological agents and the antibiotic sensitivity of the causative organisms at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Material and Methods: This was a prospective cross sectional study of 88 women with wound infection following caesarean sections at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Swabs were obtained from infected wounds over a period of 24 months. A structured Proforma designed for this purpose was used to obtain socio-demographic information and risk factors. Data collected was entered into a spread-sheet. Statistical analysis of results was done using SPSS 20.0 for windows® statistical software. Chi-square test was used to explore proportional relationship between groups. The level of statistical significance was set at P value <0.05 (providing 95% confidence interval). Results: The mean age of the women was 29.4years ± 5.6 and the mean parity was 1.73 ± 1.8. The wound infection rate was 6.7%. Unbooked status, multiple vaginal examinations, prolonged labour and prolonged rupture of membranes were all significantly associated with wound sepsis (P value <0.05). Majority 29 (33.3%) of the wound swab specimen yielded Staphylococcus aureus, all the microorganisms isolated were sensitive to ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin and least sensitive to cephtazidine and cefuroxime. Conclusion: This is the first published study to examine post caesarean section wound infection and microbiological pattern in our center and it will serve as a benchmark for the review of the current protocol for prophylactic antibiotics following caesarean section and for further research. Efforts should be made to reduce nosocomial infection in obstetric patients in order to decrease the incidence of wound infection following caesarean section especially in booked patients.

Keywords: Caesarean section, Wound infection, Microbiological pattern, Port Harcourt, Southern Nigeria

Cite this paper: Khadijah Olatayo Hassan, Justina Omoikhefe Alegbeleye, Post Caesarean Section Wound Infection and Microbiological Pattern at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Southern Nigeria, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-8. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20180601.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Caesarean section can be defined as the delivery of the foetus, placenta and membranes through a surgical incision made on the anterior abdominal wall and uterus after the age of viability. [1, 2] Worldwide, the rate of caesarean delivery is increasing due to continual review and extension of its indications. It is about 9.1% in Ilorin, 16.2% in Ibadan, 13.7% in Kano and 7.6% in Enugu however, in Port Harcourt it is 44.19%. [3-7] In the developed world, the rate is between 10% and 30% and continues to increase due to the use of modern electronic foetal monitoring, fear of litigation and social indication. [1, 2, 8] These prevalence rates are higher than the World Health Organization’s recommendation of not more than 15%. [9] The prevalence of wound infection after caesarean sections have been shown in Nigeria to vary between 5.5-29.8%. It is 16.2% in Ibadan, 9.1% in Kano and 6.5-8% in Ile- Ife. It is 22.2% in Uganda and East Africa, 4.5% in Saudi Arabia and 7- 41.1% in the UK and USA. [4, 10-16] A wound is the mechanical disruption in the continuity of soft tissues of the body structures. It can results from surgical incisions, trauma or may be pathological. Most bacteria live on our skin, in the nasopharynx, gastrointestinal tract and other parts of the body with little potential for causing disease because of first line defence by the intact skin. The development of wound infection depends on the interplay of many factors that lead to a breakdown of the host protective layer- the skin, thus disturbing the protective functions of the layer, with introduction of many cell types into the wound to initiate host response. [17] Infection of the wound is the successful invasion and proliferation by one or more species of microorganisms anywhere within the body’s sterile tissues, sometimes resulting in pus formation. [17, 18] Post-operative wound infection delay wound healing, prolong hospital stay and cause unnecessary pain. There are two mechanisms responsible for the development of post-caesarean wound infection: first, increased amniotic fluid and wound colonization by cervicovaginal flora due to prolonged rupture of membranes and prolonged labour. The second mechanism involves increased exogenous bacterial contamination by skin flora due to breaks in sterile technique, especially with difficult surgeries, unbooked status and inadequate skin preparation with solutions contaminated with bacteria. [19, 20] The risk factors associated with post caesarean section wound infection include emergency caesarean section, duration of labour, duration of rupture of foetal membranes, the socioeconomic status of the woman, booking status, number of vaginal examinations during labour and invasive foetal monitoring. These have all been demonstrated in various studies carried out on post caesarean section wound infection in Nigeria, [3, 4] Other factors include pre-existing urinary tract infection, anaemia, excessive blood loss at the time of surgery, obesity, diabetes mellitus, HIV positive status or immunsuppression and delayed prophylaxis with antibiotics or incorrect choice of antibiotics, use of general anaesthesia, the skill of the surgeon, the operative technique and duration of surgery. [19, 20] Various Studies have shown that the isolated organisms from wound infection site following either emergency or elective caesarean sections are direct contamination from the skin or vagina flora and also nosocomial infections. [3, 4, 10] With increasing number of women having caesarean deliveries, wound infection present a significant burden on health care. It is therefore important to know not only the prevalence but also the risk factors, causative organisms and antibiotic sensitivity at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Southern Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

- The study was carried out at the Obstetric unit of the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital in Rivers State from November 1, 2013 to November 30, 2015. The hospital is a 882-bed hospital located at Alakahia in Obio-Akpor local government area of Rivers state South-South, Nigeria. An average of 3,000 deliveries are conducted annually. It has the highest delivery rate among all the health facilities in the state. The complex has a total of 169 beds, with 30 beds in the antenatal ward, 80 beds in the postnatal ward, 13 beds in the first stage room, 4 beds in the second stage room, and 8 beds in the private/semi-private rooms. It also has two operating theatres in the labour ward. There are five units and each unit has four consultant obstetricians, five specialist senior registrars and four registrars with many experienced nurses and midwives. It serves both urban and rural population within and outside the state.

2.2. Methods

- This was a prospective cross-sectional study of 88 women who had post-caesarean section wound infection at the University of Port-Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Nigeria between November 1, 2013 and November, 30 2015. Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review board of the hospital. The sample size of 88 women was determined using the Kish formular. The purpose of the study was duly explained to the participants and an informed consent form was signed prior to the collection of swabs from their wounds. The socio-demographic characteristics and risk factors for wound infection were documented in a structured Profoma for each participant. Patients that refused to give consent and those that developed wound infection more than 42 days post caesarean delivery were excluded from the study. Every woman who gave consent and met the criteria was selected for the study. The specimen was collected with sterile cotton swab without contaminating them with skin commensals. All participants’ proforma were collected at the end of each day. These were properly checked for completeness and any error seen was corrected. Each proforma was marked with the same serial number of the wound swab to prevent mismatch of results. They were kept in a safe locker. The samples were transported to the medical microbiology laboratory soon after collection using Stuart transport medium. In the laboratory, the specimens were registered using serial numbers and macroscopically examined for their appearances. The wound swabs were inoculated into Blood agar, Chocolate and MacConkey's media and incubated at 35°C - 37°C for 16-18 hours aerobically. The swabs were air-dried and stained by Gram’s technique. The isolates were identified based on colony morphology. Gram-positive organisms were further characterised based on catalase, coagulase and CAMP tests. Gram negative isolates were identified to species level using Microbact 2000 12A identification panel (Oxoid, Cambridge UK). The isolated pathogens were subjected to antibiotic susceptibility test by Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion technique following the clinical laboratory standard instruction. They were tested against the following antibiotics: ampiclox, gentamycin, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, erythromycin, ceftazidime, amoxycillin and amoxycillin-clavulanic acid. The results of the wound swabs were obtained after 48 hours.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- Statistical analysis was done using statistical software (SPSS for windows® version 20). Chi square test was used for categorical variables. Results are presented as frequency tables, standard deviation and percentages. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

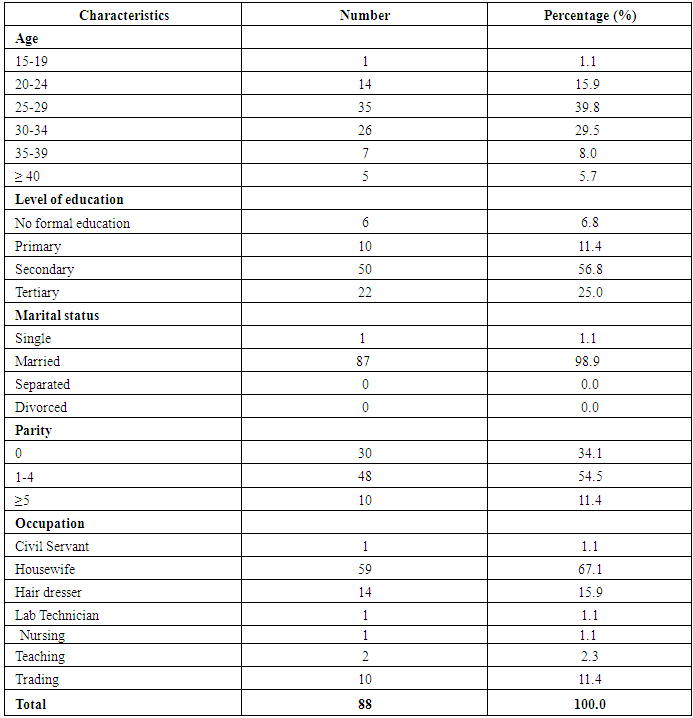

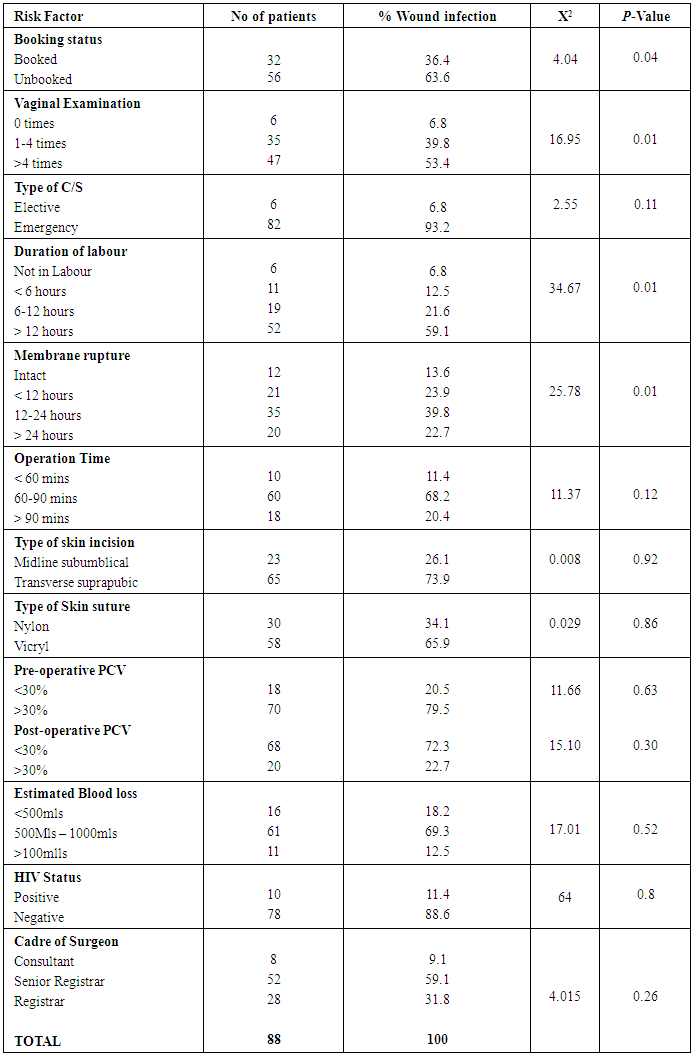

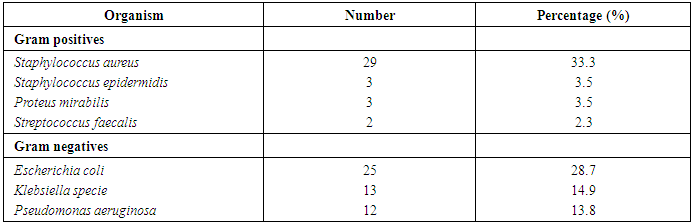

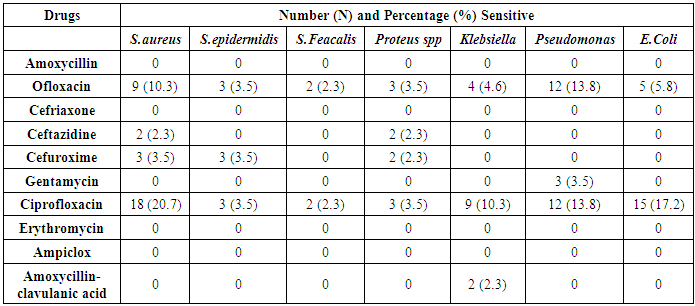

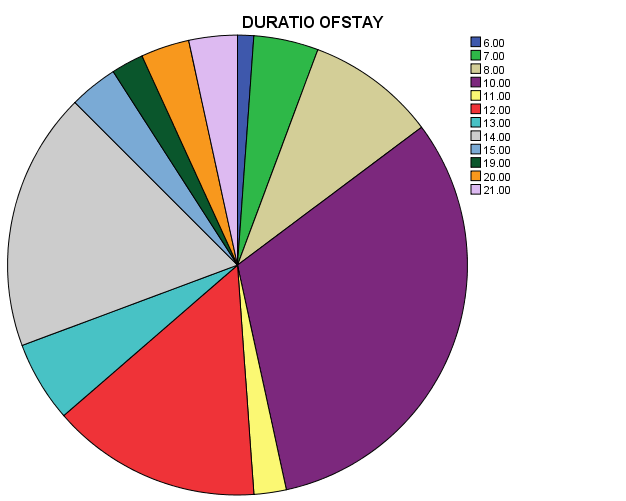

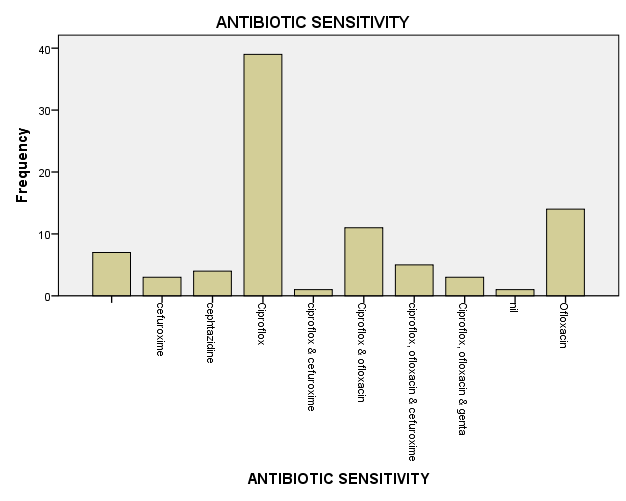

- The total number of women who delivered in the hospital during the period under review was 3,050. Of these, 1315 women were delivered by caesarean section, 900 were done as emergencies while the remaining 415 were elective cases. This gave a caesarean section rate of 43.1%. Eighty-eight of these women had clinical wound sepsis, giving a prevalence rate of 6.7%. Of these, 56(63.6%) of them were unbooked, while 32(36.4%) were booked patients. The mean age was 29.4 years ± 5.6. Majority of them were in the 25-29 years age group, thus constituting 39.8% of the population. Wound sepsis was commonest in this age group. Fifty (56.8%) of the women had secondary education, 22(25.0%) had tertiary education while 10(11.4) and 6(6.8%) had primary and no formal education respectively. About two-third (67.1%) of the women were housewives while 15.9% were hair stylists. However, there was no significant relationship between the women’s occupation and wound sepsis. Eighty-seven (98.9%) of the participants were married while only one woman was single. The socio-demographic features of the women are shown in Table 1. The result showed a statistically significant association between unbooked status, multiple vaginal examinations, prolonged rupture duration of foetal membranes and prolonged labour and the incidence of wound sepsis. However, cadre of surgeon, type of caesarean section, blood loss, HIV status, pre-operative and post-operative packed cell volume were not significantly associated with wound sepsis. This is shown in Table 2. The mean duration of hospital stay was 11.94 days ± 3.4 as shown in figure 1. Majority 29(33.3%) of the wound swab specimen yielded Staphylococcus aureus, 25(28.7%) yielded Escherichia coli, 13(14.9%) yielded Klebsiella species while 12(13.8%) had Pseudomonas infection. Only three patients’ culture yielded Proteus species, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Streptococcus faecalis respectively. However, 11(12.5%) had sterile cultures as shown in table 3. The antibiotics sensitivities of the different microbial isolates is shown in table 4 and figure 2. All the microorganisms isolated were sensitive to the quinolones: ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin and least sensitive to cephtazidine and cefuroxime.

|

|

| Figure 1. Duration of hospital stay (days) |

|

|

| Figure 2. Antibiotic sensitivity pattern |

4. Discussion

- In this study the prevalence rate of post-caesarean section wound infection was 6.7% which was consistent with the infection rate seen in other studies. [4, 10] It was however higher than the 4.5% reported by a similar study done in a tertiary hospital in Saudi Arabia, this may be due to the lower caesarean rate of 10.9% [14] compared to 43.1% in our center. However, a higher prevalence rate of 13.6% was observed in a multi-center collaborative study done in the United Kingdom. [15] Perhaps the difference in the prevalence rate may be due to the socio-demographic features of the patients, the choice of antibiotics used, timing of commencement of prophylactic antibiotics and compliance at the different centers. Nearly all our patients had antibiotic prophylaxis with ceftriazone but this did not show any significant reduction in the rate of wound infection. This may be due to the delay in commencement of antibiotics prophylaxis since there was no protocol for the timing of administration of prophylatic antibiotics for both elective and emergency caesarean sections. It may also be due to the high resistance noticed in the isolated organisms to the commonly used intravenous cefriazone in our centre and also because the centre offers all levels of care. There is evidence that such services themselves constitute a risk for wound infection. Similar observations were made in the study done in Saudi Arabia Teaching Hospital. [14] The study showed significant associations between unbooked status, multiple vaginal examinations, prolonged rupture of foetal membranes and prolonged labour with increased rate of wound infection, this is in accordance with the findings of the study done at Ibadan. [4] This similarity may be explained by the fact that both hospitals attend to both high and low risk patients and were both cross sectional studies. There was no association between the length of operation, intraoperative blood loss, cadre of surgeon, HIV status and post-caesarean section wound infection rate. The lack of significant association between nature of surgery (elective or emergency) and wound infection rate may possibly be due to the fact that majority of the surgeries were done by consultants and senior registrars, as poor surgicals skills and long operating time are said to contribute more to wound infection. Microbiological studies were done on the 88 swab samples. Of these, 77(87.5%) yielded positive cultures while 11(12.5%) were sterile. The reason for the sterile culture may be due to the commencement of prophylactic antibiotics before they developed wound infection. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated in about a third of the cultures, this was similar to the findings in Ibadan, Kano and Jodan. [4, 10] This organism is a normal skin commensal, and may have contaminated the wound during surgery possibly due to poor surgical technique. [14] This bacteria was shown to be the predominant agent in post-cesarean wound infection. [4, 10, 21] Others reported more infection with gram negative bacteria such as klebsiella species, [2] this may be because they considered both obstetric and gynaecological patients in the study. [2] Escherichia coli was the second commonest isolated organism, similar results were obtained in Kano possibly because both centres serve as tertiary centres. Most of these organisms were sensitive to quinolones, few of the isolated organisms were sensitive to third and fouth generation cephalosporins (cefuroxime and ceftazidine) but resistant to second generation cephalosporin (ceftiazone) which is the commonly used antibiotics in our centre. This is at variance with the reports from Kano, Saudi Arabia and Jordan which showed a predominance of gram positive organisms highly sensitive to cephalosporin. [10, 14, 21] Quinolones like ciprofloxacin can be used in pregnancy and postpartum as its effect on the developing fetus and baby as being teratogenic were unlikely if therapeutic doses are used. However, there are insufficient data to state categorically that there is no risk. [22] In view of this limited evidence on quinolones, it is used amongst obstetricians when the benefits outweigh the risks especially in our center where there is resistance to cephalosporins.

5. Conclusions

- The prevalence rate of post caesarean section wound sepsis was 6.7%, this is sufficient enough to give prophylactic antibiotics at induction of anaesthesia based on the sensititivy pattern of the bacteria isolates. The most common pathogens observed were S. aureus, E. coli, Klebsiella sp. and P. aeruginosa, which is in agreement with the results of ocurrent studies. The most sensitive antibiotics were the quinolones. Unbooked status, multiple vaginal examinations, prolonged rupture of foetal membranes and prolonged labour were all significantly associated with post caesarean section wound infection. The need to reduce post caesarean section wound infection is currently receiving considerable attention in recent times and requires more research. Recommendations include addressing modifiable risks factors in the antenatal period, ensuring a sterile environment, aseptic surgical and meticulous haemostatic techniques. Overall, an antibiotic policy should be developed to give proper guidelines on the use of prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the incidence of post caesarean section wound infection. This is the first study of its kind in our center, so there will be need for further studies to explore the possible contribution of skin preparation and nursing procedures to post caesarean wound infection.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML