-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2017; 5(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20170501.01

Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening among HIV Positive Women in Comrehensive Care Centres in Nairobi, Kenya

Judith Lukorito1, Anthony Wanyoro2, Harun Kimani3

1Master in Public Health Candidate, Kenyatta University, Kenya

2Senior Lecturer, School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kenyatta University, Kenya

3Lecturer, Department of Community Health, Kenyatta University School of Public Health, Kenya

Correspondence to: Harun Kimani, Lecturer, Department of Community Health, Kenyatta University School of Public Health, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

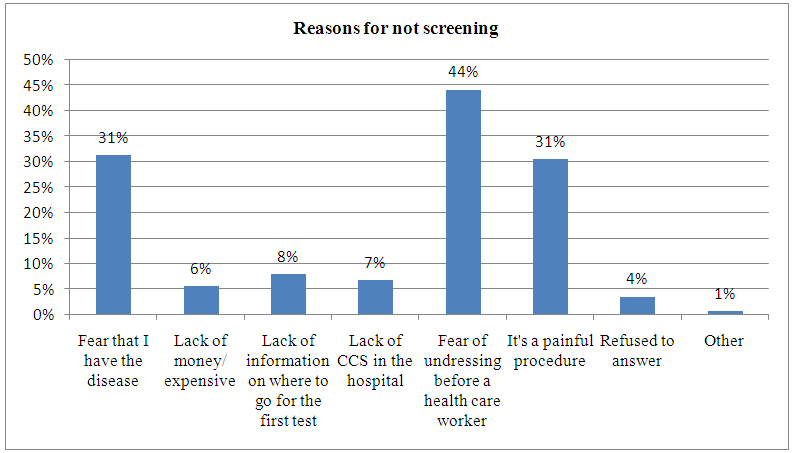

Although cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths among women in low resource settings, uptake of cancer screening services in health facilities is low. Persistent Human Papilloma Virus (Hr-HPV) infection increase risk of invasive cancerous lesion thus screening services have been incorporated into routine care of all HIV positive women. The objective of the study was to determine factors that affect uptake of cervical cancer screening services among HIV positive women in Dagoretti, Nairobi County. A descriptive, cross-sectional facility-based survey of HIV positive women in Dagoretti clinics was conducted. Data was collected using interviewer-administered questionnaire. Out of the interviewed respondents, 19% had screened for cervical cancer. Most of those who had never screened (44%) feared undressing before a health care provider. High proportion of women (72%) had good knowledge levels of cervical cancer screening. Women with higher level of education (p=0.02), those aged above 45 years (p<0.01), those with current circumcised partner (p<0.01) and those currently employed (p<0.01) had better knowledge on screening services compared to other women. Women aged 45 years and above were 2 times more likely to have been screened (OR 2.1; 1.1-3.9; P=0.021) than the younger ones. Findings of this study demonstrated that higher knowledge levels was associated with increased uptake of cervical cancer screening among HIV positive women and thus effort to improve the knowledge on cancer screening can lead to higher uptake of the services.

Keywords: Cervical Cancer Screening HIV Kenya

Cite this paper: Judith Lukorito, Anthony Wanyoro, Harun Kimani, Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening among HIV Positive Women in Comrehensive Care Centres in Nairobi, Kenya, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20170501.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among women in resource limited settings [1]. It has been reported that there are 10 to 15 new cases of cervical cancer in Nairobi each week [2] (Nairobi Cancer Registry, 2006). Despite the magnitude of the problem in Kenya and the fact that it is easily preventable, cervical cancer screening coverage in the country for all women 18 to 69 years of age is only 3.2%. According to The Kenya national guidelines on cervical cancer screening, (2012), it has been estimated that the average life years lost due to cancer of the cervix is 25.3 years. Cervical cancer is easily detectable and curable in its early stages. Unfortunately, only 5% of women in developing countries undergo screening for cervical cancer compared to over 40% in developed countries, and 70% or higher in countries that have shown marked reduction in incidence and prevalence of cervical cancer. It is therefore not surprising that in Africa—where screening rates are very low—the majority of women present at late stages with invasive and advanced disease. High risk of cervical cancer among HIV-positive women warrants the need for frequent cervical cancer screening in the general female population [3]. WHO recommends cervical cancer screening at intervals of 2 to 5 years in the general population while in HIV-positive women more frequent screening is recommended with a Pap smear at the diagnosis of the disease and a repeat screening after 6 months if negative, afterward the woman should continue on a yearly screening for life [4]. Cervical cancer is recognized as an AIDS-defining illness in HIV infection. However with HIV-positive women receiving ART and living longer, cervical cancer becomes not only a life-defining event but a disease that affects quality of life. The prevalence of HIV in invasive cervical cancer patients in Kenya is 15%, which is double the national average of 7%. Among HIV-positive women attending HIV care clinics in Kenya, 43% of the women had abnormal cervical cytological results. The presence of abnormal cervical cytology in HIV-positive women is also much higher than what is found in the general population (3.6%). With the recognition that cervical cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among HIV-positive women, the HIV program in Kenya is making significant efforts in integrating cervical cancer screening as part of the minimum comprehensive care package. However, it has also recognized that about 80% of HIV-positive clients in Kenya are not aware of their HIV status. This means that the majority of the at-risk population, do not benefit from the cervical cancer screening program when the comprehensive care centers are used as the only entry point for screenings. The Government of Kenya through the Division of Reproductive Health (DRH) has ensured integration of this service into routine care of HIV-positive women through training health care providers on how to provide the service through the `see and treat` strategy. However, a study conducted at Kenyatta National Hospital indicated uptake of cervical cancer screening services among HIV-positive women remains low, while the majority of those who have been screened presented with invasive cervical cancer [5].Most women have poor knowledge on the availability of cervical cancer screening services and its importance. Although many women may be saved by anti-retroviral therapy, they may later die of a disease that could have been detected and prevented at the facilities where they receive their anti-retroviral therapy [6]. While there seems to be an available body of knowledge on cervical cancer screening and treatment, little has been done on uptake of cervical cancer screening among HIV positive women in the Kenyan set up [7]. The main limitation to cervical screening is attributed to lack of knowledge on cervical cancer as a significant health threat to women in the general public and in the healthcare sector as presented in Kenya Medical Research Institute report of 2011 [8]. A study conducted in Eldoret, Rift valley Kenya indicated that most women do not perceive themselves as at risk for cervical cancer and therefore do not see the need for screening [9]. This could be attributed to poor knowledge of predisposing factors to cervical cancer and the available screening and treatment options as well as where to access the services. In a cross-sectional study conducted in Nigeria on cervical cancer screening services awareness, a very small proportion of respondents were aware of availability of these services and therefore very few had used it. After cervical cancer counseling a bigger proportion of the respondents were willing to uptake a Pap smear, irrespective of the cost [10]. Another study conducted in Nigeria on the willingness and acceptability of cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive Nigerian women in Lagos indicated most of the respondents interviewed had knowledge on the cervical cancer screening but the rates of screening remained very low [11]. In Kenya, on the other hand, a case study conducted in a maternal and child health clinics in Nairobi`s Kayole sub district hospital indicated that many women had poor knowledge on the benefits of a pap smear. Half of the respondents had never heard of it, while those who had an idea of what it was had not taken it up, except on a clinician’s recommendation. These differing outcomes suggest that even though the level of knowledge greatly influences the uptake of cervical cancer screening services, there seems to be other barriers to uptake of this service. Some of the factors identified to be contributory to uptake of cervical cancer screening services included level of education and profession of the respondents in Kenya. Most of the respondents went for the test only because it was a doctor’s recommendation. Other factors that were contributory included having no living child, recent HIV diagnosis and the awareness of HIV related infections. Another study in Nigeria indicate that HIV-positive women are willing to screen for cervical cancer and that the integration of reproductive health services into existing HIV programs will strengthen rather than disrupt the services [12]. The median age at diagnosis for cervical cancer is in the late 40`s and benefits of screening with avoiding cervical cancer cases has been shown most useful for women between 40 -60 years [13]. Education increases the uptake of preventive care for several reasons, because better-educated individuals have a higher efficiency in the production of health and education as well imparts self-efficacy, confidence, motivation, patience and social inclusion [14]. Number and age of children one has could also influence uptake of cervical cancer. This is because if a woman has many young children, she will have time constraints for screening as she has to rush back to cater to them8. Females with partners will be more likely to participate in prevention activities, because partners will take care for each other, and therefore their male partners will encourage them to take up screening as a preventive measure [15]. Fortunately, cervical cancer usually takes some time to progress premalignant lesions. Furthermore, available standard treatment options for the latter are effective in HIV-positive women though recurrence may be higher.

2. Methods

- A descriptive, cross-sectional facility-based design was used because cervical cancer screening takes place within health facilities and outreach centers. This design therefore enabled description of uptake of cervical cancer screening services among HIV-positive women at one point in time without influencing their behavior in any way. The study took place in all HIV care centers in Dagoretti sub-county, Nairobi County. It has a population of about 359 577 according to 2015 projected census report. Within Dagoretti, 6559 women are receiving care in HIV care centers, including the Coptic Hope Center, Mbagathi District Hospital, Riruta Satellite Heath Center, Waithaka Health Center, Ngong Road Health Center and Mutuini Health Center. The study population was made up of HIV-positive women attending routine care in the sampled facilities between 18-69 years of age, who consented to the study. The study was conducted in all the six HIV comprehensive care centers within Dagorretti sub-county. The number of respondents included in this study was distributed proportionally in each of the health centers within the sub-county. A interviewer administered questionnaire was used to collect information from respondents on social demographic factors, on level of awareness and on factors leading to uptake of these services after informed consent. This was both in English and Swahili depending on which language the participant was most comfortable with. The study was reviewed and approved by KU ethical review board. Chi square and binary logistic regression analysis was done to compare difference of those who had been screened for cervical cancer with those who had not.

3. Results

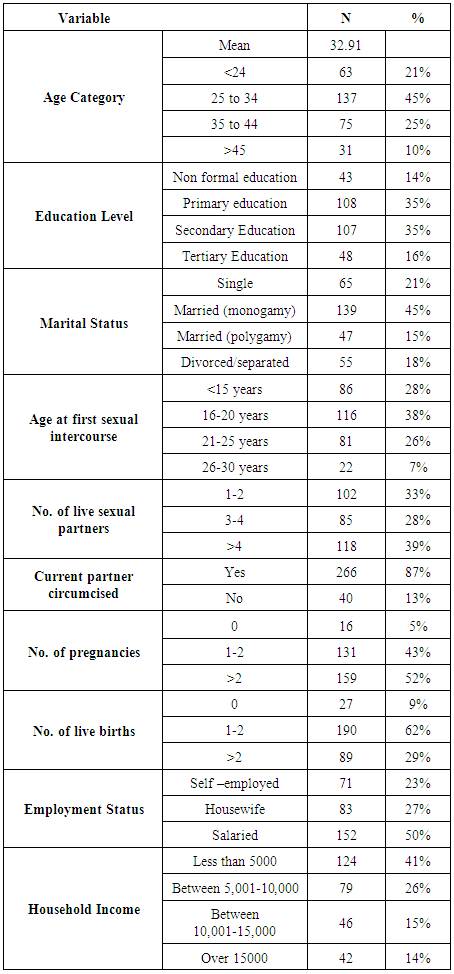

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of Study Respondents

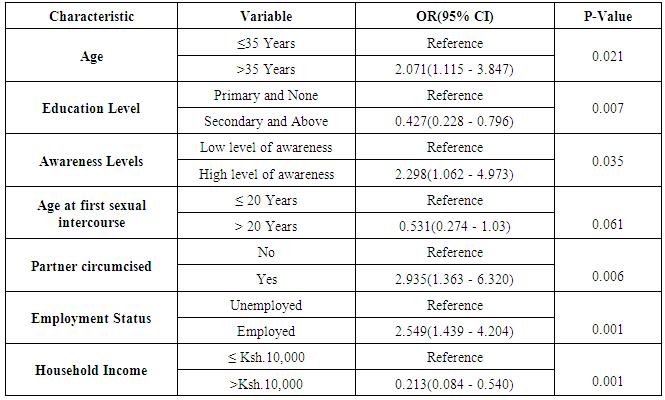

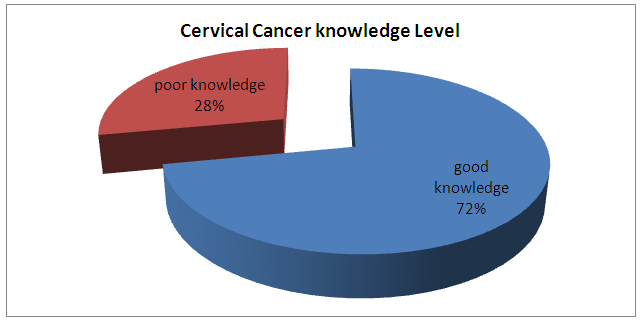

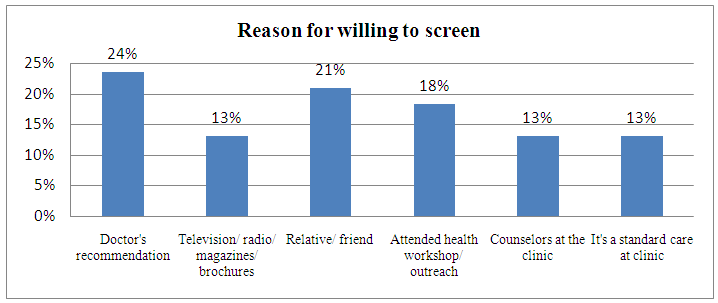

- The study respondent’s characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age of participants was 33 (IQR: 25-38); 35% of the respondents had primary level of education, and 59% of the respondents were in a monogamous marriage. Majority of the respondents reported to have been pregnant more than thrice (28%) while a bigger proportion of respondents were salaried employees (50%). Most of the respondents reported to earn less than 5000 Kenya shillings (41%) and the least of them who did not know their total monthly income were 5%. Knowledge among HIV-positive women attending care in Dagoretti revealed that 92% had access to information on cancer of the cervix and 78% had access to information on cervical cancer screening services. Out of the interviewed respondents, 84% had knowledge on cervical cancer predisposing factors on the predisposing factors while 51% of respondents had knowledge on the available cervical cancer treatment options while 49% had poor knowledge. Uptake of cervical cancer screening in Dagoretti Sub County revealed that most respondents reported to have never screened for cervical cancer (81%) and were not ready to screen on the day of the interview (88%). Most respondents were willing to screen as a result of a doctor’s recommendation (24%) while the least screened because it was either a standard care at the facility, due to counseling done at the clinic or through influence from social media (13%). Majority of the respondents were unwilling to screen as a result of fear of undressing before a health care provider (56%). Variables that were significant in the chi-square test analyses were entered into a logistic regression model to ascertain association of uptake and awareness levels. Women who were 35 years and above were 2 times more likely to have undertaken CCSS (OR 2.07, 95% CI 1.12-3.85 P=0.02). Women who displayed good awareness levels about cervical cancer screening services were 2 times more likely to take up a screening test (OR 2.30, 95% CI, 1.06-4.97, P=0.03). Women whose current partners are circumcised are 3 times likely to be more aware about cervical cancer screening services (OR 2.94, 95% CI, 1.36-6.32, p<0.01). Women in formal employment are about 2.5 times more likely to be aware about cancer of cervix screening services (OR 2.48, 95% CI, 1.31-4.70, P<0.01).

|

|

| Figure 1. Pie chart on knowledge levels |

| Figure 2. Reasons for screening |

| Figure 3. Reasons for not being screened |

4. Discussion, Conclusions and Recommendations

- This study elicited that majority of the respondents in Dagoretti Sub County had good knowledge on cervical cancer and the available screening and treatment options as they had access to information on availability of screening services within the facilities they attend. A bigger percentage had access to information on services, predisposing factors to cervical cancer screening, screening options available in Kenya and the treatment options for cervical lesions. These findings are contrary to a study conducted by Franceschi in 2007 that concluded that most women were not aware of the available screening methods. Dim et al in a Nigeria study showed that very few women were knowledgeable on the availability of screening services for this deadly disease [3]. A study conducted in Rift valley, Kenya on awareness and acceptability of cancer of the cervix screening did not agree with this study as it indicated that women have got no access to information and they believed they were not at risk for the disease [9]. According to the findings of this study, most women were aware of the predisposing factors to cancer of the cervix which should therefore promote uptake of the service though not the case at the moment. This contrary to a study by Huchko et al (2011) that indicated that most women do not perceive themselves as at risk for the disease [8]. It also elicited a fact that most women had never heard of the available treatment options nor of the interventions being put in place by the government to help curb deadly disease. This is consistent with results of a study conducted in Kayole by Kihara (2009) that showed most women had never heard of availability of treatment options for cervical cancer while those who had heard about it were not ready to take up the treatment option as they all knew cancer is a terminal illness.This agrees with a study conducted at Kenyatta National Hospital by Gichangi (2003) that found out that there seemed to be a wide body of knowledge on cervical cancer but has no impact on uptake [5]. Although the level of knowledge in this study seems to be high, uptake of the service remains low, that as indicated in the findings of this study, of the 306 respondents who were interviewed, 220 were classified as having good knowledge levels on cancer of the cervix screening services having been interviewed on information access, predisposing factors, screening procedures, treatment options and G.O.K interventions to ensure availability of the service. However, only 57 women had screened for the disease. This contradicts with a study conducted in Kasarani amongst teachers whose findings indicated a crude association between awareness and uptake of the service (Kihara et al, 2009). There is a contradiction on what is actually happening in comprehensive care centers compared to what is stipulated in the cervical cancer national guidelines. Out of the 57 women already screened for disease, only 5% (3 respondents) had screened more than three times for the disease. Following the guideline, HIV positive women are meant to screen for the disease at least twice in the first year of diagnosis, and there after once every year to ensure disease is curbed in its early stages, (National Cancer Screening Manual, 2012). This means that even though raising the level of awareness has a positive correlation to uptake of the aforesaid service, there are other underlying factors that need to be addressed in order to increase uptake as pointed out by the Kenya medical Research Institute report of 2011 [8]. Another study conducted by Olayinka (2003) in Nigeria is consistent with this study as it concluded that most women were aware of cervical cancer, predisposing factor, screening options and treatment options but uptake of the service remains low [11]. These concurring outcomes suggest that even though the level of knowledge greatly influences the uptake of cervical cancer screening services, there seems to be other underlying promoters and barriers to uptake of this service.The findings of this study were significant in understanding current cervical cancer screening knowledge levels, their association with uptake and identifying other factors that may lead low uptake of screening services. This information may be used by different cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccinators’ program stakeholders (e.g donors, HPV vaccinators, screening coordinators and managers) to develop and redesign policies, guidelines and standard operating procedures on ways of increasing cervical cancer screening services in HIV positive women. In addition, determining current levels of knowledge and factors associated with cervical cancer screening services will enable screening managers to strengthen screening and treatment program, build public confidence and increase uptake among this at risk group. Strategies to improve uptake will be put in place based on practical evidence based information generated. This may ultimately help in consolidating gains made in cervical cancer screening and treatment services program. There is need of further studies when knowledge and attitudes on cervical cancer screening among HIV positive women has been addressed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- HK was a fellow in the Afya Bora Consortium Fellowship in Global Health Leadership supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of AIDS Research and PEPFAR, grant # U91HA06801B.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML