-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2015; 3(2): 22-31

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20150302.03

Antenatal Care, an Expediter for Postpartum Modern Contraceptive Use

Shabareen Tisha 1, S. M. Raysul Haque 1, Mubina Tabassum 2

1School of Public Health, Independent University Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Education and Development Foundation-EDUCO, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Shabareen Tisha , School of Public Health, Independent University Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

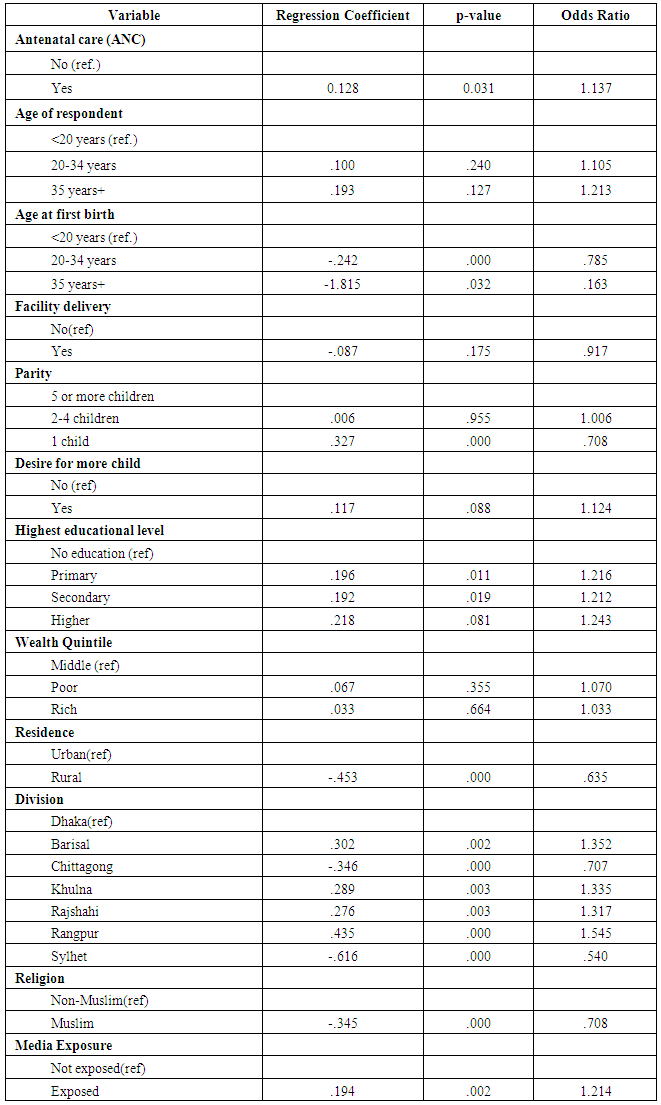

The foundation for preferment of family planning (FP) to delay conception after a recent birth is a best practice that can lead to optimal maternal and child health outcomes. However, in case of Bangladesh little is known about how pregnant women arrive at their decisions to adopt post-partum modern family planning (PPMFP). Postpartum months are a challenging time for women and they are quite neglected in our social context. This period is very much vulnerable for next conception. As ante natal care is a popular program in country in contrary to post natal care. So during ANC the advice of PPMFM would be a productive effort. The objective of this study to examine the association between antenatal care seeking behavior and the use of modern contraceptive methods among postpartum women. We used 17,842 women of reproductive ages 15–49 from the 2011 BDHS data set, who had a birth in the 5 years preceding the survey. We then applied both descriptive analyses covering Pearson’s chi-square test and later a binary logistic regression model to analyze the comparative contribution of the various maternity and socio-demographic conjecturers of uptake of modern contraceptives during the postpartum period. About 62.4% of total ANC seekers used modern postpartum family planning methods in Bangladesh. PPMFP was significantly associated with primary or secondary education (OR=1.22; OR=1.21 respectively); exposure to media (OR=1.21); religion (OR=.708) and age of woman at first birth (OR=0.97). In addition, PPMFP was associated with number of surviving children, regional variation and place of residence. This study shows the significant association between antenatal care and postpartum contraceptive use in Bangladesh. Integrating family planning counseling into antenatal care may increase the use of effective contraceptive methods among postpartum women in Bangladesh.

Keywords: Antenatal care, Postpartum modern family planning method, BDHS, Bangladesh

Cite this paper: Shabareen Tisha , S. M. Raysul Haque , Mubina Tabassum , Antenatal Care, an Expediter for Postpartum Modern Contraceptive Use, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2015, pp. 22-31. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20150302.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to World Health Organization antenatal care coverage is an indicator of access and utilization of health care during pregnancy. It’s a kind of health service that is provided during pregnancy time to all pregnant mothers’. Local coverage of at least one antenatal care visit with a skilled health personnel ranges from 71 per cent in South Asia to over 90 per cent in East Asia and the Pacific and Latin America and the Caribbean, although disparities are common within and among countries [1]. In viewing the data, it is imperative to remember that these percentages bear no reflection on either the skill level of the health-care provider or the quality of care, both of which can inspire whether such care actually succeeds in bringing about improved maternal and newborn health. Antenatal care is the service that comprises the delivery of health-related information, screening of maternal and fetal risk factors, the anticipation and management of any complication and preparation for delivery in a safe place by a skilled birth attendant [2-4]. Many studies have assessed the effectiveness of ANC on maternal and infant mortality and on their morbidity as well [5]. But a very limited number of studies examined the role of ANC as a facilitator of Family Planning (FP) use [6-8] specially post partum family planning use. According to WHO “Family planning allows individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired number of children and the spacing and timing of their births. It is achieved through use of contraceptive methods and the treatment of involuntary infertility. A woman’s ability to space and limit her pregnancies has a direct impact on her health and well-being as well as on the outcome of each pregnancy.” The motivation for the campaign of family planning (FP) is to delay conception after a recent birth which is a best practice to get the best maternal and child health outcome. On the contrary, short inter-pregnancy intervals can result in negative health outcomes such as maternal anaemia, low birth weight, and neonatal or infant mortality [9, 10].Postpartum months are a challenging time for women because of breastfeeding, childcare and recommencement of sexual relations. In a study of women residents of two Nairobi settlements of Korogocho and Viwandani, results showed that sexual resumption occurred earlier than that of menstruation and postpartum contraceptive use [10]. This puts women at the risk of conception and therefore, creates the need for postpartum contraception. Family planning is an important missed opportunity in the postnatal period. Practically all women assume that family planning information can be given during postnatal visits or before a woman leaves the hospital after childbirth. Family planning technologies for the early postnatal period, such as insertion of an intrauterine contraceptive device within the first 48 hours after childbirth, can be mentioned here. In the United States, the National Surveys of Family Growth data showed that as of 1982, most lactating women who were sexually active used a contraceptive method; barrier methods were most frequently used. However, black women and those of higher parity and lower educational level, were more likely to be sexually active and not using a method [11]. In a study, Weston, Neustad and Gilliam suggest that the facilitators to IUD uptake included strong recommendations from providers or family members, planning for IUD during pregnancy, and perceived reproductive autonomy [12]. Incidences of repeat pregnancy were reported among participants who did not obtain IUDs and instead used condoms, used no method or intermittently used hormonal methods in the same study. Planning for postpartum contraception is particularly important for pregnant women at risk of rapid repeat unintended pregnancy. Yee and Simon in 2012 in their study at a medical center in Chicago, used a qualitative approach to examine women’s perspectives toward the optimal provision of comprehensive contraceptive counseling [13]. The findings suggest that focused antenatal contraceptive counseling about postpartum contraception increased the possibility of use. Postpartum family planning (PPFP) is the term used to describe the commencement of contraceptives use during the first year after delivery [14]. The period after delivery is a complex and challenging, during which a woman has to care for her newborn child as well as cope with psychological and physical changes [15]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that both men and women, but especially women, suffer from postpartum stress and depression [16, 17]. This postpartum period presents a rising risk of unwanted conception and often frustrated desire for contraceptive protection [18, 19]. The new mothers are often sufferers of myths, fallacies and misconceptions regarding the use of contraceptives from the “informal consultants” (friends and relatives); mainly because of their inadequate knowledge and limited experience paralleled to the women of higher parity [14]. During the first days after delivery, actually contraception is probably the last thing on a new mothers’ list of priorities [20]. Moreover, the postpartum period is considered favorable for counseling women on FP methods because this period is often associated with a woman’s frequent come across with the health system [16]. Some researchers by using data from 27 countries established that within 7-9 months after delivery, most postpartum women are exposed to pregnancy, however have not took any contraceptive [18]. A number of studies have revealed that most of the postpartum mothers are not cognizant of the factors associated with fertility reappearance and do not think they are at risk of pregnancy during the first year after giving birth. In this study, we will assume that individual socioeconomic and demographic factors have role to increase the demand for postpartum family planning (PPFP) use. This conceptualization mirrors the basic beliefs of other Health-Belief Models - HBM [21-23]. The HBM has been previously applied to studies on family planning use [24, 25]. The basic argument in the HBM framework is that, there are certain factors that influence a person’s decision to use a PPFP. Bangladesh is the most densely populated country in the world. According to BBS, the population on July 20, 2014 was 156.6 million. The Health Population Nutrition Sector Development Program (HPNSDP) has a plan to increase the use of contraception to 72 percent by 2016. Currently married women in Bangladesh have 0.7 children more than their desired number and fourteen percent of them have an unmet need for FP (family planning) services [26]. This suggests that it is immensely needed to extend the access to FP services to women. In our country antenatal care (ANC) is already a well-known program rather than postnatal care. Sometimes ANC is the first interaction between a woman and healthcare provider. Many women give birth at their home. They don’t get the opportunity to receive care from any institution in their post partal life. So this ANC could act as a successful medium for promoting woman to use PPFP methods.

2. Research Hypothesis

- Antenatal care seeking behavior can increase postpartum modern family planning (PPMFP) method use. A woman when come for ANC advice during that time if she is given advice for PPMFP methods then it will be much more effective. As postpartum period is the most neglected time for a mother, so if she was previously briefed about PPMFP methods than it would act more sturdily.

3. Data and Method

- The present study uses the data from Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2011, conducted under the authority of the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. BDHS-2011 covered a nationally representative sample of 18,222 ever married women of age 12– 49 years. It is the sixth national demographic and health survey. As a sampling frame BDHS used the list of enumeration areas (EAs) prepared for the 2011 Population and Housing Census, provided by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). So the primary sampling unit (PSU) for the survey is an EA. The survey is based on a two-stage stratified sample of households. In the first stage, 600 EAs were selected with probability proportional to the EA size, with 207 clusters in urban areas and 393 in rural areas. In the second stage of sampling, a systematic sample of 30 households on average was selected per EA. Using this design; the survey selected 17,964 residential households of seven divisions of Bangladesh and 17,511 were found to be occupied. Within those households out of 18222 ever-married women, 17842 were interviewed, yielding a response rate of 98 percent. The Woman’s Questionnaire was used to collect information from ever-married women aged 12-49 years and were asked questions on background characteristics (e.g., age, education, religion, and media exposure), reproductive history, use and source of family planning methods, antenatal care, place of delivery, marriage, fertility preferences and so on. Women who had a live birth within five years before the survey were included in this study, resulting in study samples of 17,842 women. In order to make it more precise and for reduction of further recall bias the antenatal care seeking data for last pregnancy were taken.The 2011 BDHS used five types of questionnaires: a Household Questionnaire, a Woman’s Questionnaire, a Man’s Questionnaire, a Community Questionnaire, and two Verbal Autopsy Questionnaires to collect data on causes of death among children under age 5. The contents of the household and individual questionnaires were based on the MEASURE DHS model questionnaires. These model questionnaires were adapted for use in Bangladesh during a series of meetings with a Technical Working Group (TWG) that consisted of representatives from NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, International Centre for Diarrheal Diseases and Control, Bangladesh (ICDDR, B), USAID/Bangladesh, and MEASURE DHS. Draft questionnaires were then circulated to other interested groups and were reviewed by the 2011 BDHS Technical Review Committee. In our study we have used Women’s questionnaire.The dependent variable for this analysis, contraceptive use, was obtained from a question in the individual woman’s questionnaire. Women were asked two questions: “Are you currently doing something or using any method of contraception to delay or avoid getting pregnant?” If yes then “Which method are you using?” The choices are female sterilization, male sterilization, IUD, injectables, implants, pill, condom, withdrawal and others. The modern methods included pill, IUD, injection, diaphragm, condom, sterilization (male or female) and implant. Therefore, the dependent variable in this study postpartum modern family planning method was expressed as the binary variable, whether a woman utilized modern postpartum family planning or any other method rather than modern that could be traditional or lack of use of any method. Modern family planning methods are condoms, pills, implants, injectable and sterilization applicable for both males and females.The independent variables were selected for inclusion in the analysis based on their significance in previous studies of contraceptive behavior or on their hypothesized association with contraceptive use [27-30]. All the independent variables were obtained from the various sections on the women questionnaire. These are antenatal care seeking behavior, respondent’s age, respondent’s age during their first birth, parity, desire for more children, their highest educational level, wealth quintile, residence, history of facility delivery, religion, region and exposure to media. The main independent variable of interest is the service use of antenatal care during pregnancy within five years before the survey. To get the information regarding this women were asked.“Did you see anyone for antenatal care for the pregnancy?” To make analysis and interpretation simpler and more meaningful, some variables were regrouped from their original categories in the dataset. Age of respondent was categorized on the basis of <20 years, 20-34 years and 35+ years. Similar categorization was done for respondent’s age during their first birth. Parity is the representation of number of children which was further subdivided into 1 child, 2-4 children and children 5 or more. Desire for more children is considered into yes and no. Educational status of respondent was categorized on the basis of no education, primary, secondary and higher education. Wealth quintile was sectioned into poor, middle and rich group. Residence considered where the participant actually reside whether in urban or rural area. Religion again grouped into Muslim, Hindu, Christian and Buddhist community. Region is the divisional distribution of respondents’ like Dhaka, Barisal, Chittagong, Sylhet, Rangpur, Khulna and Rajshahi. Media exposure defined whether the participant is exposed to any kind of media like newspaper, radio or television.Statistical tests assumed significance at P<0.05. Bivariate statistics using Chi-square test were used to describe the association between postpartum modern contraceptive use and other independent variables. Logistic regression models were created to determine the strength of association between postpartum modern contraceptive use and antenatal checkup while controlling for other variables.

4. Results

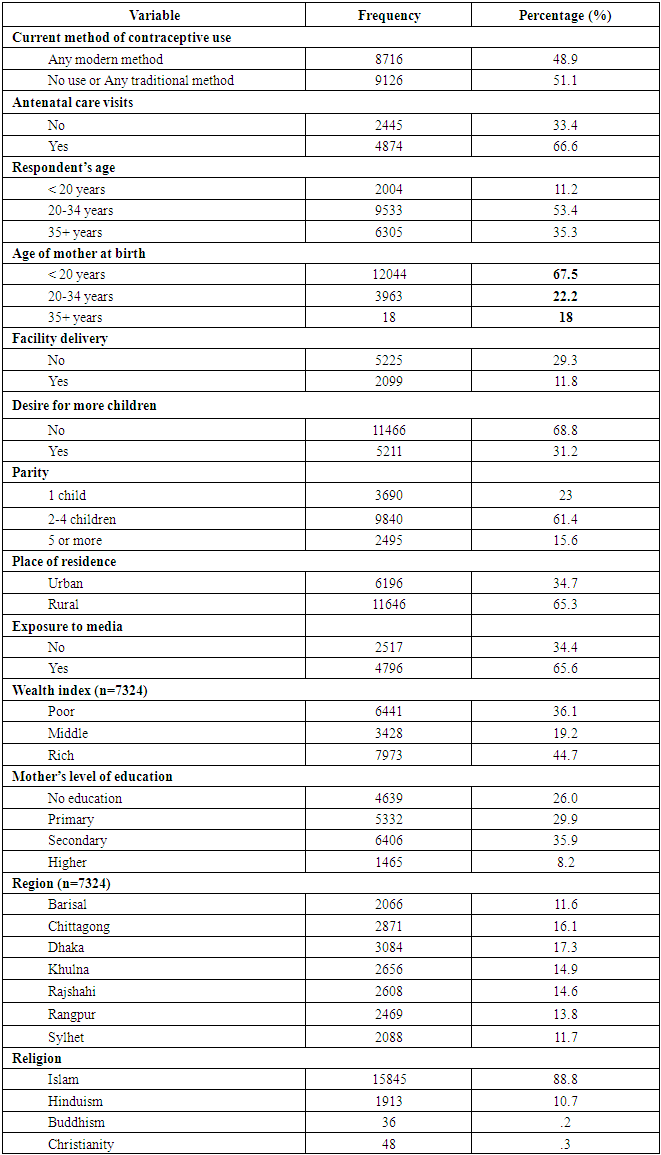

- According to descriptive analysis, given in table 1, 48.9% of our sample had adopted any type of modern contraceptive method and 51.1% respondent eitherdid not use anyfamily planning method or used traditional methods. On the other hand 66.6% of women sought antenatal care for their most recent birth and 33.4% did not do so. Most of the respondents, about 53.4% were of aged 20-34 years. About 35.3% were in 35+ age group and rest (11.2%.) were below 20 years of age. But 67.5% of women had their first birth when they were below 20years of age, only 18% had their first birth at or after 35 years of age. Considering respondents’ education level only 8.2% had attained for higher education and 26% had no education. On the other hand 29.9% and 35.9% had completed their primary and secondary education respectively. Only 11.8% had history of facility delivery and 68.8% had no desire for more children though 23% had only one child and 61.4% had less than 4 children. 65.3% of our study populations were from rural area and most of them were from Dhaka district. The least women were from Sylhet (11.7%) and Barisal (11.6%).Though Secularism is one of the four fundamental principles in our country but 88.8% of our study populations were Muslim by religion. Regarding the economic status 44.7% were rich, 19.2% were from middle economic status and rests (36.1%) were from poor economic group. In case of media exposure there were 65.6% respondents who were exposed to any kind of media and 34.4% had no history of media exposure.

|

|

|

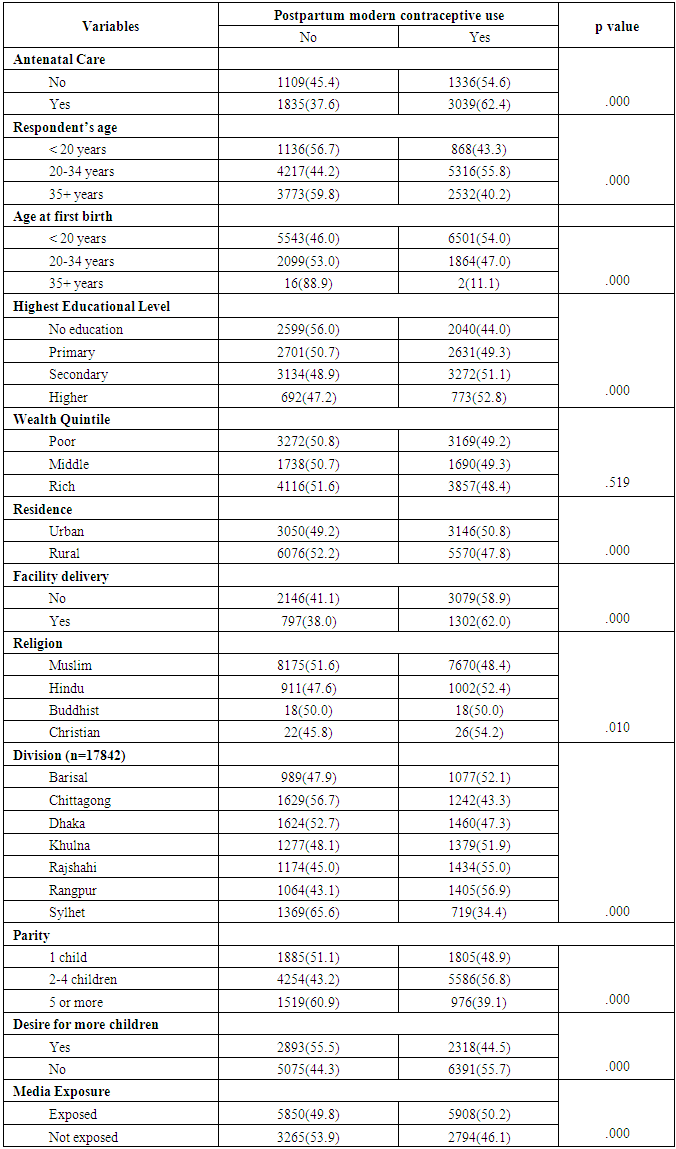

5. Discussion

- Two third of Bangladesh women (66.6%) received ANC for their last child within five years before the survey. Among them 62.4% used modern contraceptive methods. Utilization of modern PPF was significantly associated women’s: antenatal care seeking behavior, age of the woman during first birth, parity, education level, religion, exposure to the media, place of residence and divisional distribution.Our findings show that women’s antenatal care seeking behavior predicted utilization of modern PPFP. Women should be offered the opportunity during the antenatal period to discuss postpartum contraception [20]. Increment in women’s age at their first birth significantly reduced their contraceptive use. This implies that PPFP use was higher among those who had history of early child birth. This might be due to extreme aged group were previously aware about contraceptives rather than younger groups. That’s why their usage is minimal. Another significant factor analyzed was parity. Those who had one child only, they were more likely to use PPFP in comparison to those who had more than 5 children which is similar to a study conducted in Uganda [31].Women’s primary or secondary education is also an important predictor for utilization of modern PPFP .This relationship is constant with findings reported by other studies [10]. Higher educated women have a better understanding about their contraceptive usage that’s why antenatal care couldn’t play any role in their decision making. Our result couldn’t establish any relationship between wealth quintile and PPFP use. According to this study it is revealed that there is a direct association between residence and PPFP use. Rural dwellers were fewer users because they had less exposure in comparison to urban dwellers. Considering regional context women from Rangpur were quite ahead than other divisions. Sylhet shows the least result. The main reason behind this regional discrepancy is cultural barriers. People from Sylhet are so conservative that they were the least user of PPFP user in whole Bangladesh. Hence more research is needed here. Women’s exposure to family planning messages on the media increased use of PPFP. Media exposure is known to increase the use of contraceptives causing behavior change through information, education and communication (IEC) campaigns [32]. Specific family planning studies in Kenya and Bangladesh have equally reported increase in utilization of family planning methods as a result of exposure to media [33-35]. The role of antenatal care, as an entry point for gaining health knowledge and accessing other health services, has been emphasized so far (36, 37). Integration of comprehensive contraceptive counseling into routine ANC services and establishing a “one stop service”, especially in developing countries, could improve postpartum uptake of modern contraception. In Bangladesh ANC seeking rate is far better than PNC. Post natal care is not at all popular in our country. After child birth females get so involved in their activities that they do not get enough time to seek PNC. On the other hand our societal context supports pregnant women to seek ANC but not PNC. Their believe is, it’s a kind of wastage of time. So to give the message about post partum modern contraceptives ANC is the best way. So it will be obviously easier to spread the information of PPFP method through ANC. Therefore policy makers should emphasize the extensiveness ANC services to promote modern contraceptive use.

6. Conclusions

- Increasing reproductive health education among disadvantaged women during antenatal care would significantly improve the uptake of PPMFP in Bangladesh. We propose that the Bangladesh government and development partners can promote an intensified program for expansion of usage of PPMFP methods that would be delivered to women who will come for antenatal care only. This is because antennal serviceacts as a facilitator to provide access to family planning messages and to offer women various contraceptive methods. Similarly family planning messages on radio, in newspapers and television can also strengthen these efforts. We also recommend that PPMFP be fully integrated into maternal health care services. It is likely that such integration would help increase the uptake of modern family planning. Finally, there is need for further research on how male involvement and timing of postnatal care influences PPMFP in Bangladesh.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to thank National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Bangladesh for allowing us to use BDHS 2011 data for our analysis and also Dr. M. Omar Rahman, Vice Chancellor and Dean School of Public Health, for his endless encouragement and kind support regarding this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML