-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2015; 3(1): 1-4

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20150301.01

Platelet Count in Women with Pregnancy Induced Hypertension in Sokoto, North Western Nigeria

Onuigwe F. U.1, Udoma F. P.1, Dio A.1, Abdulrahaman Y.1, Erhabor O.1, Uchechukwu N. J.2

1Haematology and Blood Transfusion Science Department, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto

2Medical Laboratory Department, Holy Family Clinic, Sokoto

Correspondence to: Onuigwe F. U., Haematology and Blood Transfusion Science Department, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Pregnancy Induced hypertension is one of the most common and potential life threatening complications of pregnancy. This cross-sectional study is aimed at investigating the relationship between platelet count and pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH). Seventy (70) PIH patients (subjects) and thirty (30) healthy pregnant women (control) visiting the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department of Specialist Hospital, Sokoto and Maryam Abacha Women and Children Hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria were enrolled in the study. Platelet count was performed manually using standard methods on both subjects and control partcipants. The mean platelet count of the control (194±53.6) group was significantly higher than that of the subject group (99.7±53. 6) (p> 0.001). Low platelet count was more prevalent in the first and second trimester with mean platelet count (108±59.1) and (100.9±62.0) respectively. The mean age at marriage in subjects with PIH was found to be significantly lower compared to control (p=0.01). This study indicates that Pregnancy Induced Hypertension is associated with low platelet count. There is need to include the regular monitoring of platelet counts in the management protocols of women with Pregnancy Induced Hypertension.

Keywords: Platelet count, Pregnancy, Hypertension, Sokoto, Nigeria

Cite this paper: Onuigwe F. U., Udoma F. P., Dio A., Abdulrahaman Y., Erhabor O., Uchechukwu N. J., Platelet Count in Women with Pregnancy Induced Hypertension in Sokoto, North Western Nigeria, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 3 No. 1, 2015, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20150301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Pregnancy Induced hypertension (PIH) is one of the most common and potentially life threatening complication of pregnancy. It affects 5-8 percent of all pregnancies and is one of the leading causes of high morbidity for both mother and foetus, especially in developing countries [1]. PIH is the development of hypertension in the second half of pregnancy on two or more occasions, about four hours apart, in a woman who previously been normotensive, and in whom blood pressure (BP) return to normal with six weeks of delivery. Pregnancy induced hypertension is essentially a disease of primigravidia and is more common in the age group of <20 and >35 pears. When the condition is present in multipara, it is commonly associated with multiple pregnancy, essential chronic hypertension and chronic renal disease. In a previous report in Lagos on low birth weight babies, it was found that PIH complicated twin pregnancies in 21.8% of cases, almost twice the figure of 12.4% for singleton pregnancies [2]. Pregnancy induced hypertension can be classified into; gestational hypertension or pregnancy induced hypertension alone without proteinuria. Pregnancy induced hypertension without intervention can progress to eclampsia, which is characterized by hypertension, proteinuria, oedema and epileptiform convulsions requiring emergency caesarean section [3]. The importance of the problem is linked to the significant morbidity and mortality potential of pregnancy induced hypertension. The mother may develop disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute renal failure, stroke (ischaemia, due to vasospasm and microthrombosis or even haemorrhage due to severe thrombocytopenia), acute pulmonary oedema, cerebral oedema, placental abruption, liver haemorrhage/rupture, transformation in chronic hypertension, or even maternal death (preeclampsia is the second cause of maternal death linked to pregnancy) [4]; the foetal sufferance seems to be due exclusively to the placental insufficiency and may include: pregnancy loss, foetal death inutero, intrauterine growth restriction, premature labour [5]. On a long term, a woman with a history of preeclampsia has a chance to repeat it at a future pregnancy [6] and a higher cardiovascular risk [5, 6]. Also, a 2.5 times higher rate of dying by ischaemic cardiovascular disease [7]. Pregnancy induced hypertension (blood pressure greater than 140/90) occurs before or after 20 weeks gestation with no proteinuria. The clinical manifestations of maternal preeclampsia are hypertension and proteinuria with or without coexisting systemic abnormalities involving the kidneys, liver, or blood. HELLP syndrome is a severe form of preeclampsia and involves haemolytic anemia, elevated liver function tests (LFTs), and low platelet count [8]. There is paucity of data on the effect of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension on the platelet count. The aim of this case-control study was to investigate the effect of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension on the platelet count.

2. Material and Methods

- Study areaThis present cross-sectional study was carried out at the Department of Haematology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto State, Nigeria in collaboration with the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department of Specialist Hospital, Sokoto and Maryam Abacha Women and Children Hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria. The hospitals are secondary health facilities in the Northwest geopolitical zone of Nigeria offering routine quality care to residents of Sokoto metropolis and neighbouring states of Zamfara and Kebbi. Sokoto State is located in the extreme North Western part of Nigeria near to the confluence of the Sokoto River and the Rima River. Report from the 2007 National Population Commission indicated that the state had a population of 3.6 million [9].Study settingThe study was conducted in the Haematology Department of Faculty of Medical Laboratory Science in collaboration with the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department of Specialist Hospital, Sokoto and Maryam Abacha Women and Children Hospital, Sokoto.Study subjectsThe subjects for this cross-sectional case-control study included consecutively-recruited seventy (70) pregnant women with hypertension and thirty (30) subjects without complication in pregnancy will serve as control.Informed consent Written informed consent was obtained from all participants recruited into this study (controls and subjects). Ethical clearanceEthical clearance was obtained from the ethical committee of Specialist Hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria.SubjectsThe subjects for this case-control study included seventy consecutively-recruited pregnancy induced hypertensive pregnant women visiting the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department of Specialist Hospital, Sokoto and Maryam Abacha Women and Children Hospital, Sokoto in North Western Nigeria. Thirty normal pregnant women served as control. MethodsTwo milliliters of blood sample was drawn aseptically using the S-Monovette vacutainer blood collection system (Sarstedt, Numbrecht, Germany) from the median antecubital vein of all the subjects and control participants into EDTA-anticoagulated tubes. The blood was diluted with the diluent (1% ammonium oxalate) by 1 in 20 dilutions (0.02 ml of blood and 0.38ml of diluent) and platelets were counted using Improved Neubauer ruled counting chamber (Hawksley, UK) and the number of platelets per litre of blood was calculated using the first principle. Inclusion criteriaAll consenting, adult (≥ 18 years) pregnant women who were confirmed to have pregnancy induced hypertension by an Obstetrician constituted the subjects for this subjects.Exclusion criteriaNon-consenting, non-adult pregnant women with other pregnancy-related complications were excluded.Statistical analysisThe data was collected into an excel spread sheet. Collected data was analyzed statistically using statistical software SPSS Version 17.0 (Chicago Illinois). Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics of percentages, mean and bivariate analysis of t-test and Fisher’s exact test. Correlation was compared using linear regression analysis. Differences were considered significant when p <0.05.

3. Result

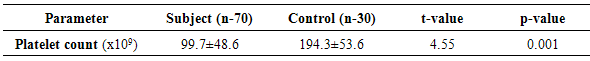

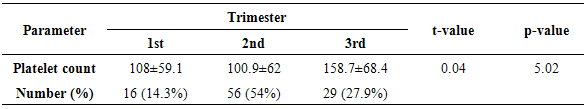

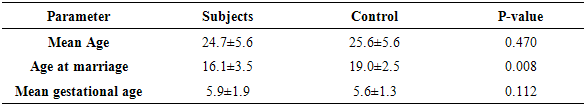

- The study subjects had mean age of 24.7±5.6 years compared to the control present age 25.6±5.8 years. The mean platelet count for the subject was significantly lower among subjects compared to the control (p=0.001). Table 1 shows the mean platelet count of subjects and controls. The platelet count of subjects was higher in the third trimester (158.7±68.4) compared to the second trimester (100.9±62) and the first trimester (108±62) (p = 0.04). Table 2 shows effect of trimester of pregnancy on platelet count of PIH patient. The demographic characteristics (age, age at marriage and gestational age) of the PIH subject and the control was determined. There was a significant relationship between age at marriage and PIH. The mean age at marriage for the subject with PIH was 16.1±3.5 years while age at marriage of the control was 19.0±2.5 years (p = 0.01). There was no statistically significant difference in the mean age and gestational age of subjects and controls. Table 3 shows effect of demographics on incidence of PIH among subjects.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- In this study, we investigated the platelet count of seventy pregnant women with pregnancy induced hypertension. We observed a significantly lower platelet count among pregnant women with PIH compared to controls. There seems a significant relationship between low platelet count and PIH. Our finding is consistent with findings from previous study [10] which observed a low platelet count among PIH patients. The aetiology and pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia still remain poorly understood. It is however often characterized by suboptimal uteroplacental perfusion associated with a maternal inflammatory response and maternal vascular endothelial dysfunction and platelet count falling to below 100 x 109/L [11]. We observed that trimester of pregnancy has effect on the platelet count of patients with PIH. The platelet count of subjects with PIH was lower in the first and second trimester compared to the trimester platelet count. The difference however was not statistically significant. This finding is consistent with result obtained in a previous study [12]. Our finding is however at variance with a previous report [13] which indicated that low platelet count is more apparent during 3rd trimester of pregnancy. The variation in platelet count among pregnant women with PIH may be due to an increased consumption with reduced life span and increased aggregation by increased levels of thromboxane A2 at placental circulation [14]. It might also be due to incomplete trophoblastic inversion of the uterine spiral arteries resulting to placental ischaemia followed by release of anti-angiogenic proteins that lead to endothial dysfunction [15].In this study we investigated the effect of three demographic variables (gestational age, present age and age at marriage) on the platelet count of pregnant women with PIH. The mean age at marriage of the subjects with PIH was found to be significantly lower compared to controls. Our finding is consistent with a previous report [15], which indicated that majority of patients affected by PIH are teenagers because of early marriage. Similarly, our finding is also consistent with a previous report which indicated that teenagers faced increased risks of several obstetric complications including eclampsia [16-18]. Teenage pregnancy is a growing problem in most Africa settings [19] including Northern Nigeria particularly in rural areas. In developing countries, the increase in teenage pregnancy rates has been attributed to early age of marriage, cultural permissiveness, low socioeconomic status of parents, lack of knowledge of sexuality education, peer group influence, lack of knowledge, ineffective use of contraceptives and family instability and disorganization which may be caused by poverty [20].

5. Conclusions

- In this study, we observed that pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) is significantly associated with low platelet count and that teenage pregnancy is significantly associated with low platelet count among patients with PIH.

6. Recommendations

- We recommend that routine and regular monitoring of platelet count be included in the routine antenatal check-up among pregnant with PIH. Patients with low platelet count should be under the management of qualified obstetrician throughout pregnancy to avoid the risk of bleeding. There is need for increased awareness and education to highlight the role of teenage pregnancy in the incidence of PIH. Reduction in platelet count among patients with PIH should necessitate urgent referral to secondary healthcare facility to avoid the serious clinical consequences of these conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We wish to appreciate all the pregnant women that participated in this study. We are also grateful to staff of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department of Specialist Hospital, Sokoto and Maryam Abacha Women and Children Hospital, Sokoto, Nigeria for their collaboration.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML