-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology

p-ISSN: 2326-120X e-ISSN: 2326-1218

2013; 2(4): 48-54

doi:10.5923/j.rog.20130204.02

Maternal Risk Factors for Low Birth Weight in a District Hospital in Ashanti Region of Ghana

Michael Ofori Fosu1, Iddrisu Abdul-Rahaman2, Riskatu Yekeen3

1Lecturer, Department of Mathematics and StatisticsKumasi Polytechnic, P.O Box 854, Ghana

2National Service Personnel, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Kumasi Polytechnic, P.O Box 854, Ghana

3Final Year Student, Department of Mathematics and StatisticsKumasi Polytechnic, P.O Box 854, Ghana

Correspondence to: Michael Ofori Fosu, Lecturer, Department of Mathematics and StatisticsKumasi Polytechnic, P.O Box 854, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study examines the prevalence of low birth weight (LBW) among infants and its association with maternal risk factors in Manhyia District Hospital of Kumasi Metropolis in Ghana. Thiswas a facility study based on a cross sectionalstudy from the maternity ward of the hospital.A sample of 1,200women within the reproductive age (15 - 49 years) across the district and beyond between 2010 and 2012 were selected from a total delivery of 24,025 for the survey.In this study, a multiple logistic regression was used to determine the relationship of maternal risk factors and low birth weight.The estimated LBW prevalence was 21.1% which is comparable to other developing countries and higher than other parts of the worldespecially among the developed countries. This stands to reason that the rate indicates a public health problem (ACC/SCN, 2000). The factors observed to be highly significantly associated with LBW included Antenatal Care (p-value =0.0040), Haemoglobin level (anaemia) (p-value =0.0020),Residence (p-value =0.0000) and Fetal infection (p-value=<0.0000) There is also risk for maternal age (p-value=0.0160. All other variables considered such as gestational age, weight, height, and babys’ sex were not significant (p-values > 0.05).In a nutshell, fetal infection, haemoglobin level (anaemia in pregnancy), antenatal care and residence are highly significantly risk factors associated with LBW at the hospital. Early/late maternal age also showed some level of significance with LBW. Gestational age, height weight, and babys’ sex among others were however not significant.

Keywords: Low Birth Weight, Maternal Risk Factors, Prevalence Rate, Infants

Cite this paper: Michael Ofori Fosu, Iddrisu Abdul-Rahaman, Riskatu Yekeen, Maternal Risk Factors for Low Birth Weight in a District Hospital in Ashanti Region of Ghana, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 2 No. 4, 2013, pp. 48-54. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20130204.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Childbirth all over the world comes with joy not only for the new-borns’ parents but the family at large. It attracts attention from both close relations and community members. Typically in Ghana, the family members, especially the women clad themselves in white clothing from headgear to footwear. However, the course of pregnancy is not given such needed attention. The onus lies solely with the woman who is pregnant despite the fact that scientific literature has indicated that the outcome of pregnancy depends on both external and internal factors experienced by the pregnant woman[1].Birth weight is an important indicator of reproductive health and general health status of population. Low birth weight (LBW) continues to remain a major public health problem worldwide especially in the developing countries. It is considered the single most important predictor of infant mortality, especially deaths within the first month of life [1, 2].Low birth weight infants are those who weigh less than 2.5 kg at birth and it usually happen with pre-term birth. A pre-term birth is defined as birth before 37 weeks of gestation. Half of all perinatal and one third of all infant deaths are directly or indirectly related to LBW[4]. A child’s birth weight or size at birth is an important indicator of the child’s vulnerability to the risk of childhood illnesses and the chances of survival. Children whose birth weight is less than 2.5 kilograms, or children reported to be “very small” or “smaller than average” are considered to be small or of low birth weight and have a higher risk of early childhood death. Those who survive have impaired immune function and increased risk of disease are likely to remain undernourished, with reduced muscle strenght throughout their lives, and may suffer a higher incidence of diabetes and heart disease later in life[3, 32]. Children born underweight also tend to have a lower IQ and cognitive disabilities, affecting their performance in school and their job opportunities as adults[5, 14].The increase in survival rates of LBW infants leads to increasing health care costs due to extensive hospital stays. It is estimated that extremely LBW babies are up to six times as costly as normal weight babies (Chang, 2003; Klingenberg et al; 2003).Pre-term delivery of low birth weight infants (PLBW) is on the increase and gradually becoming an important problem in both developing and developed countries. In spite of consistent efforts to improve the quality of maternal and child health, more than 20 million infants in the world (15.5% of all births) are born with low birth weight[4]. Ninety-five per cent of them are in developing countries with the rate of low birth weight in developing countries being more than double that of developed countries (16.5% and 7% respectively). In Sub- Saharan Africa, the rate is around 15%[35].

1.1. Maternal Anthropometry and Pregnancy Outcome

- The causes of low birth weight are complex and interdependent, but the anthropometry of the mother and her nutritional intake are thought to be among the most important. Pre-pregnancy weight, body mass index (BMI) and gestational weight gain all have strong, positive effects on foetal growth suggesting that energy balance is an important determinant of birth outcomes[34,40]. The WHO collaborative study on maternal anthropometry and pregnancy outcomes, using data from 111,000 women from across the world reported that mothers in the lowest quartile of pre-pregnancy weight carried an elevated risk of Intrauterine Growth Retardation (IUGR) and LBW of 2.55 (95% CI 2.3, 2.7) and 2.38 (95% CI 2.1, 2.5) respectively, compared to the upper quartile. Attained maternal weight at 20, 28 or 36 week of gestation showed even higher odds ratios for IUGR of 2.77, 3.03 and 3.09 respectively when women were compared between quartiles of highest to lowest attained weight. This is possibly because it considers weight gain in pregnancy including that of the foetus. Women in the lowest quartile for both pre-pregnancy weight and weight gain during pregnancy were found to be at highest risk (up to week 20, O R 5.6; up to week 36, O R 5.6) of producing an IUGR infant[40].

1.2. Effect of Socio-economic Status

- Studies worldwide have examined the effect of socio-economic status (SES) indicators, including maternal education, on birth weight and IUGR. Maternal illiteracy and low SES have been shown to be major risk factors for IUGR[11, 25]. In the developing world, lacking proper health systems and resources, the level of maternal education may be of prime importance in the determination of health outcomes of mothers and their infants and children. In the Bangalore cohort study, a decreasing trend of IUGR was observed with an increase in maternal education, ranging from 46 per cent in women who had no schooling to 19 per cent in women who had a post-graduate education (T. Sarah, unpublished observations). In addition, the odds of IUGR for women with a high school education or below was 1.5 (95% CI: 1.04, 2.17) when compared to those with pre-university education, thereby underlining the importance of maternal education in determining a host of health-related behaviour/ practices. It is important to understand that while achieving the universal primary education is laudable for Ghana, promoting education to higher levels should be the ultimate goal. Factors relating to the care of women, environmental hygiene and sanitation, household food security, and poverty are all likely to operate simultaneously with a low level of maternal literacy in the aetiology of low birth weight and IUGR.In Ghana, the issue of birth weight and factors influencing it has not received much needed attention. This should be an issue of public health concern as a nation because birth weight is a strong predictor of an individual baby’s survival and a person’s personality[9, 10]. The recommended weight at birth should be in the range of 2.5kg to 4.0kg[12]. From 1998 to 2004, Ghana recorded higher LBW cases of 16% compared to the average of 14% for sub-Saharan Africa[15]. The 2006 MICS report, however, found the prevalence rate to be 9.1%. The difficulty is that only 2 in 5 babies were weighed at birth[14]. Though the major and primary determinant of birth weight is gestational age[17, 19], there are other secondary factors that also bear, either directly or indirectly, on determining the weight of a baby at birth. These are maternal age, maternal weight gain, pre-pregnancy weight, maternal height, parity, marital status, placental malfunction, smoking, heredity, gender of baby, working hours, and various socio-economic factors[16, 20, 21, 22]. In developing countries, the major determinants of LBW babies are racial origin, nutrition, low pre-pregnancy weight, short maternal stature, and malaria[23]. A World Health Organization Collaborative Study of MaternalAnthropometry and Pregnancy Outcomes reported that weight gained at 5 or 7 lunar months was the most practical screening for LBW and IUGR[25]. The reduction of the incidence of low birth weight also forms an important component of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) on child health. Activities towards the achievement of the MDGs will need to ensure a healthy start in life by making certain that women commence pregnancy healthy and well nourished, and go through pregnancy and childbirth safely[13]. Low birth weight is, therefore, an important indicator for monitoring progress towards these internationally agreed - upon goals. Earlier works stated the birth weight of infants in Ghana ranged from 2.00 kg to 3.00 kg[28, 29].With this background and fortified by the fact that limited number of such facility based prospective studies are available, we undertake the present study to define the extent of LBW problem in Ghana and investigate the martenal risk factors associated with this condition using the Manhyia district hospital in the Kumasi Metropolis of Ashanti Region as a case study.

2. Subjects and Methods

- This was a cross sectional facility study. The hospital serves the entire Manhyia district with a female population of about 486,327 (GSS, 2010 Ghana Population and Housing Census) and beyond.Subjects were selected from over 24,025women who delivered at the maternity ward of the hospital. The subjects were all women who delivered at Manhyia hospital within the years 2010 and 2012. One thousand two hundred (1,200) who delivered at the hospital during 2010 and 2012 were sampled. The selection procedure was systematic random sampling from a frame of folders for the women who delivered at the facility in the years under study. In our study, we excluded all stillbirths and multiple births that occurred during these years. Only singleton births and live births were included. Relevant information related to maternal factors, namely; age, socio-economic factors, antenatal services, residence/location (urban, rural), gestational age, haemoglobin levels, placental malfunction, weight, height, mothers’ education, fetal infection, babys’ sex among others were studied. The information were then captured and analysed using SPSS 17 software.The World Health Organization definition of LBW was used. i.e., birth weight less than 2.5 kg to delineate between normal birth weight and LBW.

2.1. Model Specification

- The following generalized linear logistic model was used

| (1) |

The link is not a linear function,

The link is not a linear function,  probability of LBW,

probability of LBW,  is the model matrix including mother’s age, educational level, antenatal care, haemoglobin level of mother, gestational age, and sex of baby. The matrix also includes geographical location, such as ethnic background and whether the respondent is from rural or urban environment;

is the model matrix including mother’s age, educational level, antenatal care, haemoglobin level of mother, gestational age, and sex of baby. The matrix also includes geographical location, such as ethnic background and whether the respondent is from rural or urban environment;  is the vector of parameters, and

is the vector of parameters, and  is the vector of residuals. The Fisher scoring method was applied (SAS, 2007) to obtain Maximum Likelihood estimates of

is the vector of residuals. The Fisher scoring method was applied (SAS, 2007) to obtain Maximum Likelihood estimates of  The overall goodness of fit is derived from the Likelihood Ratio Test of the hypothesis

The overall goodness of fit is derived from the Likelihood Ratio Test of the hypothesis  where a comparison is made between the full model and the model that contains only the intercept (Hilbe and Greene, 2008). Therefore it is a test for global null hypothesis of the elements of the solution vector.

where a comparison is made between the full model and the model that contains only the intercept (Hilbe and Greene, 2008). Therefore it is a test for global null hypothesis of the elements of the solution vector.2.2. Goodness of Fit Test

- For basic inference about coefficients in the model the standard trinity of Likelihood-based tests, Likelihood ratio, Wald and Lagrange Multiplier (LM), are easily computed. For testing a hypothesis, linear or nonlinear, of the form;

| (2) |

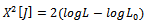

subject to the restrictions of the null hypothesis, for example subject to the exclusions of a null hypothesis that states that certain variables should have zero coefficients. That is, they should not appear in the model. Then the likelihood-ratio statistic;

subject to the restrictions of the null hypothesis, for example subject to the exclusions of a null hypothesis that states that certain variables should have zero coefficients. That is, they should not appear in the model. Then the likelihood-ratio statistic; | (3) |

is the log-likelihood computed using the full or unrestricted estimator,

is the log-likelihood computed using the full or unrestricted estimator,  is the counterpart based on the restricted estimator and the degrees of freedom J, the number of restrictions.Each predictor, including the constant, can have a calculated Wald Statistic defined as

is the counterpart based on the restricted estimator and the degrees of freedom J, the number of restrictions.Each predictor, including the constant, can have a calculated Wald Statistic defined as | (4) |

defines both the z or t statistic, respectively distributed as t or normal. For computation of Wald Statistics, one needs the asymptotic covariance matrix of the coefficients.

defines both the z or t statistic, respectively distributed as t or normal. For computation of Wald Statistics, one needs the asymptotic covariance matrix of the coefficients.3. Empirical Results

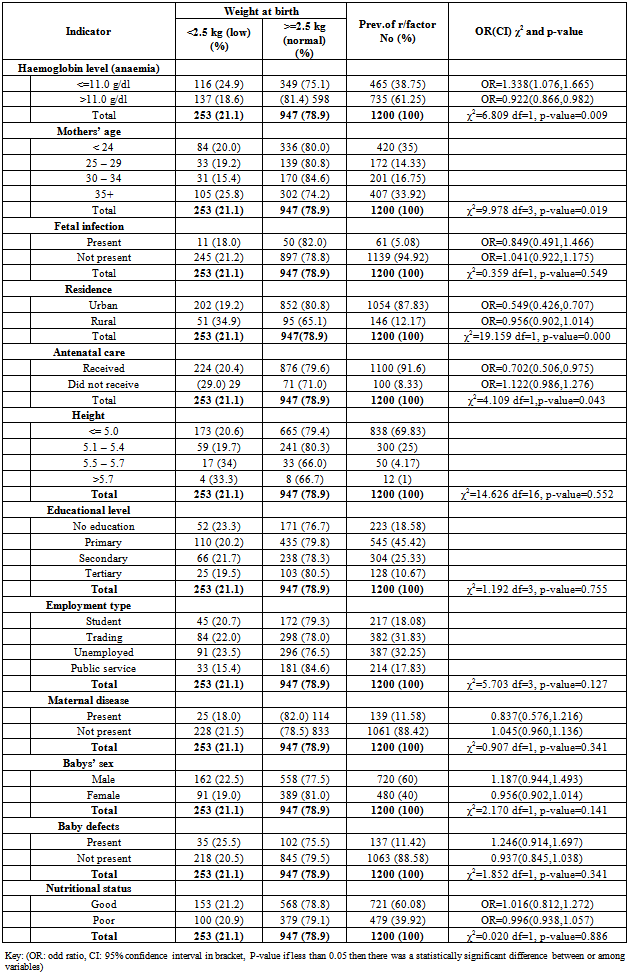

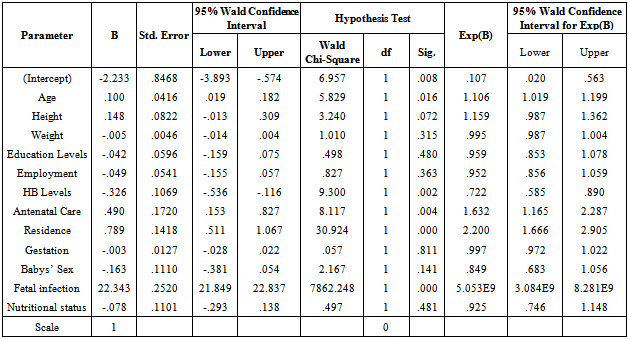

- Out of the total of 1,200 mothers sampled, 153 gave birth to babies who weighed less than 2.5 kg., giving the LBW prevalence in this study as21.1% (from our sample of non-missing weights). Table 1 provides a descriptive view of the different categories. Mothers who are anaemic are more likely to give birth to low birth weight babies than non anaemic mothers (25.0% versus 18.6%). Women from rural households, those who are not working or studying or into petty trading and those who have a maximum of secondary school education are more likely than more advantaged women to give birth to children of low birth weight. For example, the proportion of low birth weight among women who have a maximum of secondary school education is 90.1%, compared to 9.9% of women who have tertiary level education. Women in rural households are likely to give birth to children of low birth weight compared to those in urban households (34.9% versus 19.2%). Women who have assured or permanent jobs are more likely to give birth to normal weight children compared to children whose mothers are unemployed or do not have permanent jobs or are schooling. The rate is however quite predominant amongs women who are unemployed. The possibility of giving birth to children of low birth weight among women who do not attend antenatal care is higher than those who receive antenatal care even once (29.0% versus 20.4%). The results also show that male children are likely to have LBW than female children at birth (64% versus 36%). Women who are short have a high risk of giving birth to LBW children than those who are tall. Further more, women who are lessthan 24 years or above 35 years have highest proportion of children weighing less than 2.5 kg. Table 2 depicts the results of multivariate logistic analysis of maternal factors associated with LBW. The factors observed to be highly significantlyassociated with LBW includefetal infection (p-value=0.0000), residence (p-value=0.0000), haemoglobin level (p-value=0.0020) antenatal care (p-value=0.0040) andmothers’ age (p-value=0.0160).

|

|

4. Discussion

- Findings from this study show that most of the womenwho gave birth at the Manhyia district hospital were in the less than 24and 35+ year age group. This was responsible for the highest proportion of low birth weight infants. The percentage of lowbirth weight observed in this study (21.1%) is similar to that reported in the Eastern Africa countries[37].The 21.1% prevalence of low birth weight (mean =

and the normal mean birth weight of

and the normal mean birth weight of  observed in this study is comparable to other studies in the developing world[26]. The missing link is that few mothers in Ghana give birth at health facilities and hence their babies are not weighed at birth. The descriptive statistics show that mothers in rural areas tend to give birth to low birth weight children than women who live in urban areas. Fetal infection is found to be a risk factor for low birth weight as mothers who had this condition gave birth to LBW babies compared to mothers without the condition.The results also show that male children are likely to have LBW than female children at birth (64% versus 36%). Again, women who have higher education tend to give birth to normal birth weight babies than women who are not educated or have low levels of education. Women who are into full time employment are more likely to produce normal birth weight babies than those who are unemployed or into casual work. Women who receive antenatal care services even once tend to give birth to normal weight babies than those who receive no antenatal services. (29.0% and 20.4%) respectively. Short women have a high risk of giving birth to LBW children than those who are tall.The association of haemoglobin level (anaemia), antenatal care, residence, fetal infection and maternal age with low birth weight observed in this study has also been reported from other developed and developing countries. The prevalence of LBW which ishigher than the 15% threshold, should be a source of worry to the district and the metropolis as a whole in that other studies for instance Ofori et al,[28] indicate that a lot of pregnant mothers do not give birth at health facilities and as such their babies are not weighed at birth.Looking at the length of confidence interval of estimated odds (table 1), we find that haemoglobin levels is estimated with 95% confidence having the shortest interval length. In the descriptive analysis, the prevalence of low birth weight among the rural mothers are 0.956 times higher than that of the urban mothers. The prevalence of LBW among mothers who did not receive antenatal care is 1.122 times higher than those who received antenatal care. On the other hand, LBW observed among women within 25 – 34 age group is 1.106 better than those within <24 years and 35+ years. Again, the prevalence of LBW among anaemic mothers is 1.338 times higher than non anaemic mothers.The risk of delivering LBW was higher in women who had no or low education, poor economic status (or unemployed), live in rural areas, received no antenatal care, under 24 years and above 35 years, had fetal infection and were anaemic.

observed in this study is comparable to other studies in the developing world[26]. The missing link is that few mothers in Ghana give birth at health facilities and hence their babies are not weighed at birth. The descriptive statistics show that mothers in rural areas tend to give birth to low birth weight children than women who live in urban areas. Fetal infection is found to be a risk factor for low birth weight as mothers who had this condition gave birth to LBW babies compared to mothers without the condition.The results also show that male children are likely to have LBW than female children at birth (64% versus 36%). Again, women who have higher education tend to give birth to normal birth weight babies than women who are not educated or have low levels of education. Women who are into full time employment are more likely to produce normal birth weight babies than those who are unemployed or into casual work. Women who receive antenatal care services even once tend to give birth to normal weight babies than those who receive no antenatal services. (29.0% and 20.4%) respectively. Short women have a high risk of giving birth to LBW children than those who are tall.The association of haemoglobin level (anaemia), antenatal care, residence, fetal infection and maternal age with low birth weight observed in this study has also been reported from other developed and developing countries. The prevalence of LBW which ishigher than the 15% threshold, should be a source of worry to the district and the metropolis as a whole in that other studies for instance Ofori et al,[28] indicate that a lot of pregnant mothers do not give birth at health facilities and as such their babies are not weighed at birth.Looking at the length of confidence interval of estimated odds (table 1), we find that haemoglobin levels is estimated with 95% confidence having the shortest interval length. In the descriptive analysis, the prevalence of low birth weight among the rural mothers are 0.956 times higher than that of the urban mothers. The prevalence of LBW among mothers who did not receive antenatal care is 1.122 times higher than those who received antenatal care. On the other hand, LBW observed among women within 25 – 34 age group is 1.106 better than those within <24 years and 35+ years. Again, the prevalence of LBW among anaemic mothers is 1.338 times higher than non anaemic mothers.The risk of delivering LBW was higher in women who had no or low education, poor economic status (or unemployed), live in rural areas, received no antenatal care, under 24 years and above 35 years, had fetal infection and were anaemic.5. Conclusions

- The results of this study suggest that for reducing LBW, the strategy needs to focus attention on nutrition education to facilitate better weight gain during pregnancyfocusing more on the girl-child education, regular antenatal care visits and discouraging teenage and old age pregnancy as well as formulating policies that will reduce poverty among rural women and creating more jobs. The girl child education policy must also be given all the needed resources it requires to achieve the desired set targets. Frequent checks for any fetal infection and haemoglobin levels on women who attend antenatal care (ANC) must be stepped up for early detection of fetal infection / complications and prevention of anaemia. Free ANC services must be provided for all pregnant women to encourage regularattendance to health facilities even whether they are on National Health Insurance Scheme or not.The low variability in birth weight that was explained by independent variables used in all the regression models suggests that there were some confounding factors not accounted for. Within the limits of this research however, fetal infection, antenatal care, haemoglobin level (anaemia), maternal age and residence contributed significantly in predicting birth weight at Manhyia district hospital in the Kumasi metropolis.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML