Zarbo G, Coco L, Leanza V, Genovese F, Leanza G, D’Agati A, Giannone TT, Giunta MR, Palumbo M A, Carbonaro A, Pafumi C

Department Obst and Gyn University of Catania, Italy

Correspondence to: Pafumi C, Department Obst and Gyn University of Catania, Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Aerobic vaginitis is a syndrome due to the alteration of the vaginal biota with different bacterial, clinical and immunological characteristics with respect to the classic form of vaginitis. From a clinical point of view the infection is characterized by the presence of yellowish, bad-smelling secretions, redness, itching, congestion of the vaginal mucosa and different levels of dyspareunia, toxic leucocytes and parabasal epitheliocytes, negative KOH test, and raised vaginal pH.We studied 243 pregnant women between the 16th and the 39th week of gestation who all underwent a vaginal swab and antibiogram. The presence of aerobic vaginitis was found in 147 pregnant women who then underwent pharmacological therapy together with their partners.Aerobic vaginitis is one of those diseases that is prevalently transmitted by sexual contact and if it is not diagnosed and treated early, during pregnancy can place the health of both the mother and the fetus at risk as it is associated with preterm birth, pPROM and chorioamnionitis.It is therefore very important diagnosing it early and treating with a correct pharmacological therapy that, as can be seen from our study, reduces the adverse effects associated with these types of infections.

Keywords:

Aerobic Vaginitis, Vaginal Biota, Vaginal Secretion, Pregnancy

Cite this paper: Zarbo G, Coco L, Leanza V, Genovese F, Leanza G, D’Agati A, Giannone TT, Giunta MR, Palumbo M A, Carbonaro A, Pafumi C, Aerobic Vaginitis during Pregnancy, Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Vol. 2 No. 2, 2013, pp. 7-11. doi: 10.5923/j.rog.20130202.01.

1. Introduction: Vaginal Biota

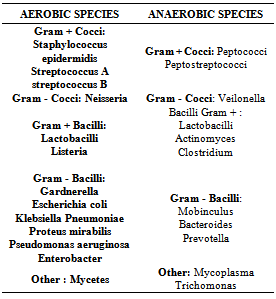

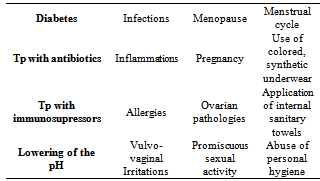

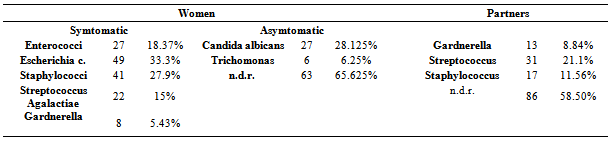

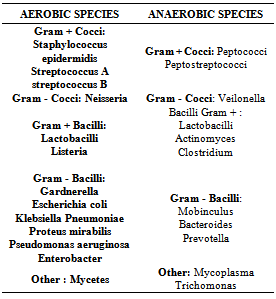

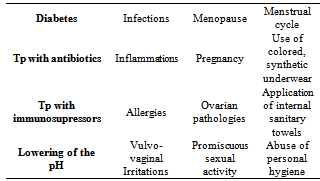

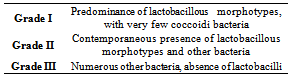

The vaginal biota, in fertile age, is populated by non-pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms (aerobic and anaerobic) that in equilibrium among themselves and with the host, constitute the so called “vaginal bacterial flora” (Table 1).This equilibrium is maintained by Doderlein’s bacilli that represent 90% of the total virginal microorganisms; aerobic and anaerobic pathogens make up less than 10%. This ratio 1/10, does not allow pathogens to overgrow and cause disease.The vaginal bacterial flora changes with the various phases of a woman’s life, in fact, in prepubescent age, it is made up of Gram-positive and anaerobic Gram-negative cocci and the vaginal pH is neutral with respect to adulthood. This means that there are no natural defenses and there is a greater disposition towards infection. In fertile age the vaginal bacterial flora has mainly Doderlein’s bacilli with a vaginal pH between 4 and 4.5.In menopause, due to the lack of estrogen, the mucosa atrophies with a decrease of glycogen, Doderlein’s bacilli In cases of disease or pharmacological treatment or risky sexual habits (Table 2) there is an increase in the vaginal pH with the overgrowth of pathogens and the consequent increase of the risk of infective vaginitis.Table 1. Vaginal bacterial flora

|

| |

|

Table 2. Factors that influence vaginal pH and the onset of VB

|

| |

|

1.1. Aerobic Vaginitis: Definition and Etiology

The scientific community has classified vaginitis as specific vaginitis (Trichomonas vaginalis and candida) and bacterial vaginitis. However, in 2002, Donders and co-workers[1, 2] proposed a third class of vaginitis, “aerobic vaginitis”, to identify a pathology that was not included in the previous classification.Aerobic vaginitis, in fact, is a syndrome coming from the alteration of the vaginal biota with bacterial, clinical and immunological characteristics not referable to the above mentioned vaginitis. This condition is a pathology caused by an abnormal vaginal flora.The vaginal biota is colonized by microorganisms of intestinal origin and the most isolated are E.coli, which alter this micro-environment; the presence of other microorganisms is minor and does not appear to be correlated with aerobic vaginitis[3].From a clinical point of view the infection is characterized by the presence of yellowish, bad-smelling secretions, redness, itching, congestion of the vaginal mucosa and different degrees of dyspareunia, toxic leucocytes and parabasal epitheliocytes, negative KOH test, and an increased vaginal pH.

1.2. Aerobic Vaginitis: Diagnostic Approach

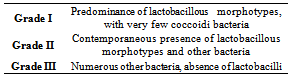

The diagnosis of aerobic vaginitis is based essentially on a microscopic examination[1,2]. However, to obtain a certain diagnosis it is necessary to associate the level of lactobacilli to 4 variables:1. Proportional number of leucocytes (Table 3)Table 3. Grade lattobacillare

|

| |

|

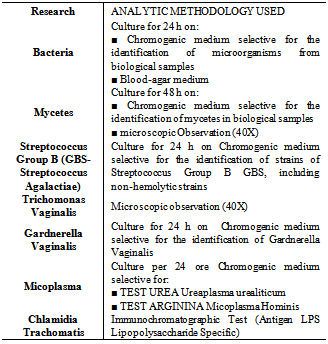

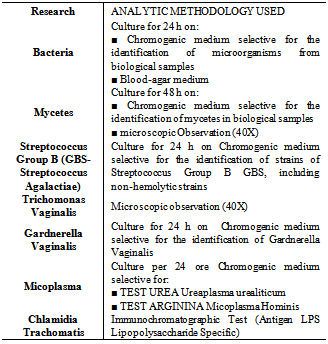

2. Presence of toxic leucocytes 3. Type of bacteria present4. Presence of parabasal epithelial cellsTo each of these parameters a score is given that ranges from 0 to 2 (AV score). An AV score of 1-4 represents the normal vaginal biota, between 3 and 4 indicates a slight aerobic vaginitis, between 5 and 6 indicates a moderate aerobic vaginitis and an AV score between 6 and 10 indicates a severe aerobic vaginitis.However, other than these parameters, the following must be present: yellowish virginal secretion, high vaginal pH (>5), and negative KOH test[1, 2, 3].Other characteristics are dyspareunia, vulvovaginal itching, cervical erosion with isolation of microorganisms that are not within the originally proposed criteria[3].The cultural microbiological examination, when necessary, requires a vaginal swab of the posterior fornix; the culture is carried out on different media (Table 4). Finally, it is also possible to carry out biochemical tests using techniques such as T- RFLP[4, 5, 6, 7] and PCR-DGGE[8].Table 4. Culture media

|

| |

|

1.3. Aerobic Vaginitis: Therapy

The therapy of choice for aerobic vaginitis has a double goal: the eradication of the pathogen by means of a correct antibiotic therapy and the re-establishment of the homeostasis of the vaginal biota to prevent the conditions that favored the onset of infection.It is opportune to use topical drugs that do not have the side effects of the same drug when administered systemically and that reduce the phenomenon of resistance.The drug of choice is Kanamicina, an aminoglycoside whose efficacy has been demonstrated by Tempera et al.[3, 9].This study showed that Kanamycin:• is ineffective on lactobacilli;• is efficacious on the complicated enterobacteriaceae bacterial forms;• has high in situ concentrations • can be associated with metronidazole for the complicated anaerobic forms.Another class of antibiotics used for aerobic vaginitis is the quinolones (Furnieri et al.)[10]. Metronidazole and clindamycin, active against anaerobic bacteria and some protozoa, thus suitable for bacterial vaginitis, are not indicated for aerobic vaginitis.

1.4. Aerobic Vaginitis and Pregnancy

Pregnancy is a period in which the vaginal biota, conditioned by high estrogen levels, has a good supply of glycogen and a high percentage of lactobacilli flora, which can exceed 90% of the microorganisms present in the vagina during fertile age. The remaining ~5% is made up of other aerobic and anaerobic bacterial species that are responsible, due to their quantity and quality, for the flogistic modifications that can trigger infective processes with sequelae for the pregnancy.Aerobic vaginitis in pregnancy produces a notable production of pro-inflammatory cytokines which are, as it’ s known, associated with events such as preterm birth, pPROM and chorioamnionitis.

2. Our Study: Materials and Methods

The institutional review board of our Department approved the study protocol, which conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration. All women provided informed written consent before enrollment in the study. The study was not advertised, and no remuneration was offered. At the Institute of Pathological Obstetrics and Gynecology of the “Santo Bambino” Hospital in Catania, Italy, from March to December 2010 we carried out vaginal swabbing with antibiogram on 243 pregnant women between the 16th and the 39th week of gestation.Of these, 147 (60.49%) had bad-smelling vaginal secretions, whitish in color, adherent to the walls, itching, burning and notable pelvic and vaginal pain. The remaining 96 patients (39.51%), had whitish vaginal secretions but were asymptomatic.Of the 147 symptomatic women, 70 (47.62%) had had anal intercourse before pregnancy, of which 49 women with two partners and 21 with three partners. Moreover, in all the patients, other than the vaginal swab, a colpo-cyto-bacteriological examination and urine culture with antibiogram were carried out.In 7 (4.76%) of the 147 symptomatic patients, who had notable pain, burning and edema of the labia majora, we carried out the cultural test of a removed hair bulb. For the 243 partners of the pregnant women we carried out uretral swab, semen culture, urine examination and in 13 cases (5.35%) with previous prostatitis, the Meares-Stamey test.

3. Our Study: Results

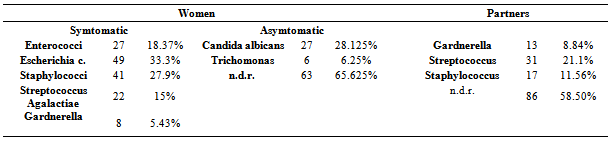

From the results of our study (Table 5) it can be seen that 96 asymptomatic patients with a whitish vaginal secretion had a colpo-cyto-bacteriological examination showing that in 27 (28.125%) there was the presence of candida albicans and in 6 (6-25%) infection from Thricomonas. In the remaining 63 (6.625%) no pathology was found.Of the 147 symptomatic women we found 27 (18.37%) with infections from Enterococci, 49 (33.3%) from E. coli, 41 (27.9%) from Staphylococci, 22 (15%) from Streptococcus Agalactiae and 8 (5.43%) from Gardnerella.The 7 (17.07%) women who had had the hair bulb examination, of which 5 had infections from staphylococci, were included in the group of 41 women with infections from Staphylococci.In the partners of the 147 symptomatic patients we carried out the Meares-Stamey test that was positive for Gardnerella in 13 (8.84%), showed infections from streptococci in 31 (21.1%) and infections from Staphylococci in 17 (11.56%). These bacteria were also isolated in the urine. The remaining 86 (58.50%) showed no infections.Table 5. Results

|

| |

|

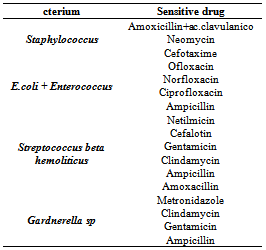

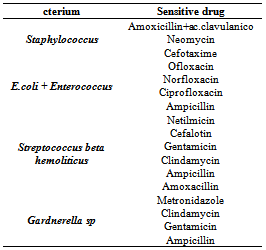

From the analysis of our data it was also seen that 43.29% of the bacteria were present at a count of 1,000,000 UFC, 19.1% with a count of 100,000 UFC, 14.41% with a count of 10.000 UFC and the remaining 23.2% with a count of 1,000 UFC.The antibiogram was carried out testing 11 drugs for each swab and the treatment used the antibiotic towards which the pathogen was most sensitive and could be administered during pregnancy. Table 6 shows the drugs towards which the pathogen was most sensitive.Table 6. Most sensitive drugs detected by antibiogram

|

| |

|

4. Our Study: Therapy

Based on the antibiogram the patients with aerobic vaginitis, and their respective partners, received a pharmacological therapy for 15 days and a vaginal swab 15 days after the suspension of the therapy. This showed that the therapy had been efficacious in 131 (89.12%) patients while the remaining 16 (10.88%) women underwent a new vaginal swab followed by correct therapy. The second cycle of treatment, using different drugs with respect to those used before, eradicated the infection in the 16 women (10.88%) who had had the second swab.

5. Conclusions

Aerobic vaginitis is a disease transmitted prevalently by sexual contact, which if not diagnosed early and treated correctly, can diffuse in the genital apparatus and, during pregnancy, cause preterm birth, pPROM and chorioamnionitis. Our study shows how a correct early therapy can avoid these complications.The cure of one eventual bacterial infection of the genito-urinary apparatus does not confer immunity, thus there is always the possibility of re-infection and an adequate form of prevention is essential.The prevention of sexually transmitted diseases can be helped by the use of condoms and the knowledge that some sexual practices are more at risk than others for infection, also in women who use oral or mechanical contraceptives, in as much as they do not reduce this risk.Preventative measures are opportune and other than the use of a protective barrier during sexual intercourse it is useful to adopt good personal hygiene practices:1. Reduce to a minimum the use of vaginal douches, above all if a woman is predisposed to vaginitis, in as much as they reduce the concentration of Doderlein’s bacilli. 2. Wash genitals in the direction vagina-anus and not the opposite direction so as to not diffuse the bacteria of the anal area to the vagina and the bladder. 3. Avoid sprays for personal hygiene, harsh or perfumed soap that reduce the natural perineal protection 4. Avoid tight fitting or synthetic underwear that trap humidity and facilitate infection.5. Always inform the partner or partners of any infection and advise that he/she seek a specialized medical examination/treatment.6. Always verify that any cure is complete in the patient and partner/s.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Valentina Pafumi has carried out English language editing for this article.

References

| [1] | Donders GGG, Vereecken A, Bosmans E, Dekeersmaecker A, Salembier G, Spitz B: Definition of a type of abnormal vaginal flora that is distinct from bacterial vaginosis: aerobic vaginitis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2002; 109:34. |

| [2] | Donders GG: Definition and classification of abnormal vaginal flora. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 21:355. |

| [3] | Tempera G, Abbadessa G, Bonfiglio G, Cammarata E, Cianci A, Corsello S, Raimondi A, Ettore G, Nicolosi D, Furneri PM: Topical kanamycin: an effective therapeutic option in aerobic vaginitis. J Chemiother 2006;18:409. |

| [4] | Zhou X, Brown CJ, Abdo Z, Davis CC, Hansmann MA, Joyce P, Foster JA, Forney LJ: Differences in the compositions of vaginal microbial communities found in healthy Caucasian and black women. ISME J 2007; 1:121. |

| [5] | Yamamoto T, Zhou X, Williams CJ, Hochwalt a, Forney LJ: Bacterial populations in the vaginas of healthy adolescent women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2009; 22:11-18. |

| [6] | Thies FL, Konig B: Rapid characterization of the normal and disturbed vaginal mirobiota by application of 16 S rRna gene terminal RFLP fingerprinting. J Med Microbiol 2007;56:755. |

| [7] | Schutte UM, Abdo Z, Bent SJ, Shyu C, Williams CJ, Pierson JD, Forney LJ: Advances in the use of terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis of 16S rRNA genes to characterize microbial communities. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2008; 80:365. |

| [8] | Vitali B, Pugliese C, Biagi AND, Candela M, Turroni S, Bellen G, Donders GG, Brigidi P: Dynamics of vaginal bacterial communities in women developing bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, or no infection, analyzed by PCR- denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and real-time PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007;73:573. |

| [9] | Tempera G, Bonfiglio G, Cammarata E, Corsello S, Cianci A: Microbiological/clinical characteristics and validation of topical therapy with kanamycin in aerobic vaginitis: a plot syudy. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2004;24:85. |

| [10] | Furneri PM, Mangiafico A, Giummarra V, Roccasalva LS, Tempera G: In vitro susceptibilities to various antibiotics of lactobacillus spp. isolated from vagina. Abstr 108th General Meet American society for Microbiology, Washington, ASM, 2008, pp1-5, abstr A-022. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML